TRANSFER Gallery

Kelani Nichole, founder of the pioneering time-based art gallery, talks about how she has explored stewardship and preservation through collecting.

As a software engineer with a long-time interest in creative uses of technology, Andrew Badr is the ideal collector of generative work—what he refers to as the current “mainstream of software art.” He started paying attention to Art Blocks in the spring of 2021, then dove into the field headfirst with the release of Tyler Hobbs’s Fidenza that June. Not only did Badr devote a substantial amount of time to collecting and trading outputs, but he also spent hours in the Art Blocks Discord discussing the project and learning more about Hobbs’s process. Badr channeled his enthusiasm toward educating others. He put together a public Google Doc with information and analysis on the Fidenza algorithm, going beyond what the artist has published, and used the platform Deca to present a selection of outputs from the project that demonstrates its range. In the interview below, Badr discusses his experience as a collector, his own experiments with software art, and options for displaying a collection of generative work.

My interest in software art started during my early days online. Sometimes I would come across people using the web in ways that weren’t just practical or commercial. They were using the idioms of the user interface or the medium to do something really new. In high school I started making websites and trying to do weird stuff with them, like having the navigation be in a circle and the content around the outside edge. When I went to college I studied computer science, not art. But I made a program that interpreted text inputs as changing patterns of colored rectangles. It was playing on the idea that any text could be code.

Your World of Text is a site I launched in 2009. It’s an infinite canvas with a grid of characters. Anyone can click anywhere on it and write something or overwrite text that someone else wrote. You can scroll in any direction indefinitely. The infinitude of it was something I hadn’t seen before. I don’t know if it was the first infinite interactive canvas on the web, but it could have been. It was partly inspired by the interface of Google Maps, where you can click and drag to move around. It was tile-based in the same way. It was also inspired by my mental model—accurate or not—of the universe being infinite. You can go in any direction, there just might not be stuff there yet. If you find an empty space, you can still be in that space. The response to the site was immediate and it took off more quickly than I thought.

Now with NFTs it feels like there’s a mainstream of software art. Back then it felt pretty outsider-y. There were communities of people who were passionate about it. There was some academic interest, too. People called it “net art” and wrote about hypertext in analytical ways. But there were no persistent spaces where people were talking about software art. I came to New York in 2015 and studied at the School for Poetic Computation. That was great for me as someone who had made some art and seen cool stuff but had never met people I could talk to about it. I learned a lot about the history of generative art and creative coding techniques from Zach Lieberman, who is a great teacher. Only recently have I become aware that people back then were already making software art in a collectible way and producing editions. Before NFTs I wouldn’t have known how to collect software art, besides writing down URLs I was excited about.

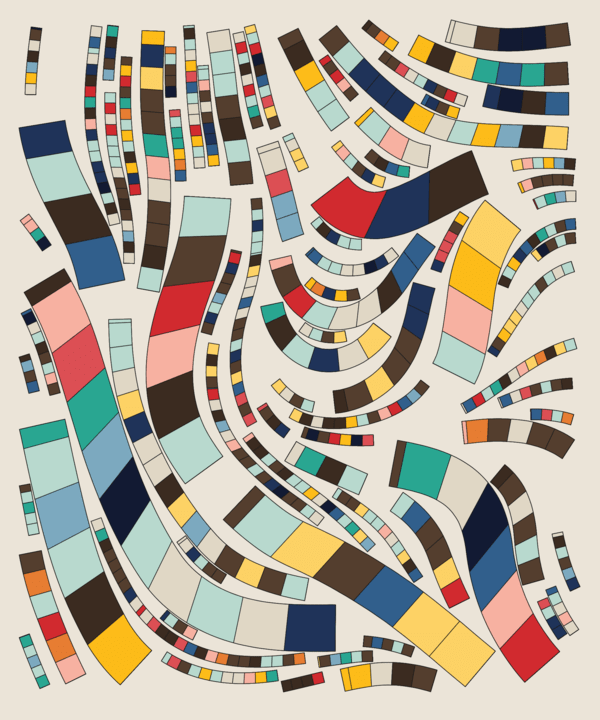

I started paying attention to NFTs in April 2021. I collected a few things but didn’t go deep down the rabbit hole until two months later, when Tyler Hobbs released Fidenza. I got obsessed with that project because it combined the beauty of individual pieces with variety across the collection. I’d seen generative art before, but I’d never seen a series like that. I remember refreshing the page as the outputs were coming off the minter and being in awe. I minted a couple, then bought a bunch on secondary. The amount of money I was paying seemed pretty crazy to me because I was new to the NFT space, and the concept of buying purely digital work still felt really foreign. But I had a strong instinct around it, and I trusted myself. I bought one piece at 2 ETH, which was a record high at the time. I think I set the record a couple of times.

After that I was hooked. I hung around the Art Blocks Discord, chatted with other collectors, followed people on Twitter. When you’re excited about something it’s great to be able to meet other people who are excited about it, so you can share your observations and opinions. The Art Blocks Discord also has people who are talking not about art but about money and investments. It’s hard to have one without the other in the NFT space. I don’t think it’s the most wholesome or respectful approach to talking about art. But it seems to come with the territory.

Tyler has been making generative art since 2014, and before Art Blocks it was a different world. Since releasing Fidenza, he has done some pioneering work exploring alternatives to the Art Blocks model. Incomplete Control (2021) and QQL (2022) both experiment with the mechanics of minting. Incomplete Control is a reaction to the concept of traits in Art Blocks series, where an individual piece gets assigned to a color palette or a layout. Art Blocks collectors get obsessed with the rarity of traits, and Incomplete Control did away with that. It’s a generative art series with continuous values for all its different aspects. It was released at a live minting event with Bright Moments, using a modified version of the Art Blocks engine.

If you’re using randomness in a computer program to make art, you’re selecting from sets of options. Exposing those options to collectors increases the surface area for their appreciation. QQL, which Tyler developed in collaboration with Dandelion Wist, invites collectors into that process. The QQL algorithm has tremendous variety, and you can play with it and mint an output you like. In early generative art, the artist curated the outputs. In Art Blocks, nobody curates them. QQL introduces the possibility of the collector curating the outputs. If Tyler had decided to do another standard Art Blocks project after Fidenza, he would have been successful. But I appreciate that he has continued to look for other ways of doing things.

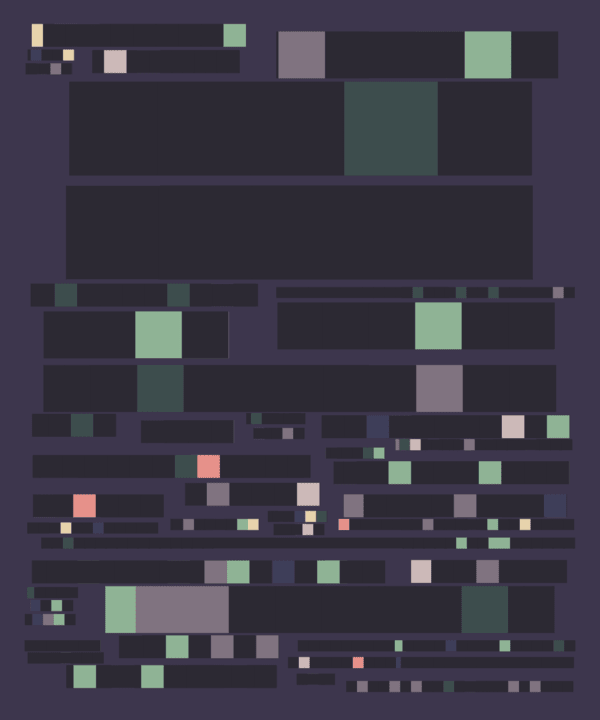

Loren Bednar’s phase (2021) has a small cohort of fans. Whereas Fidenza arguably resembles certain strains of painting, phase is natively digital. Each phase tells a story and evokes a different feeling. They’re these beautiful washes of color. They feel liquid. They have interference patterns. They’re narrative in a way that even other animated series of Art Blocks aren’t. It has something to do with the time scale at which they play out—different elements appear and disappear and ultimately cycle back to the beginning. They unfold and change in surprising ways, and there’s emotion in the movement. There’s something that feels dramatic. Elements talk to each other, almost like characters entering or leaving the canvas.

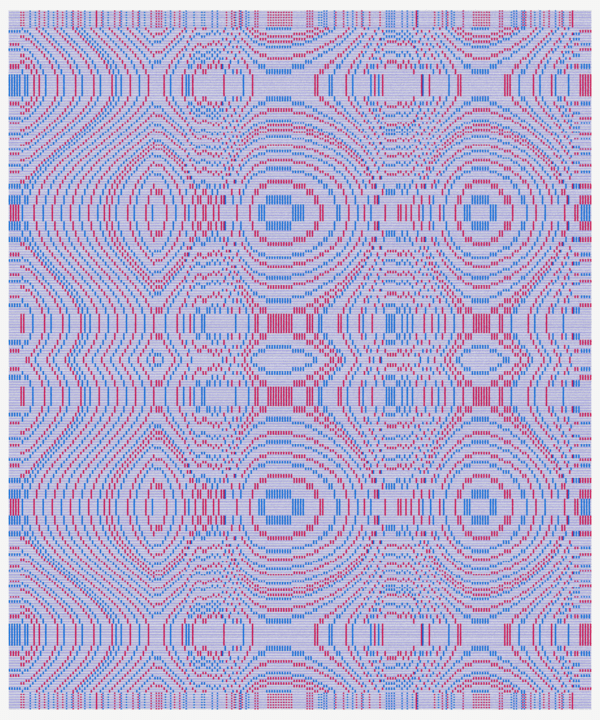

Perpetua (2022) by Punch Card Collective builds on the deep historical connection between weaving and programming. Two of my closest friends worked on this project. They didn’t just want to visually model weaving, they implemented code in a way that simulates weaving. There’s a very realistic loom simulation behind the scenes. That creates a lot of variety, and you can order a Perpetua as a woven blanket. I have one and it’s really nice.

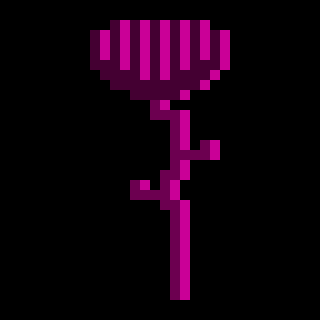

Beyond Art Blocks I’m interested in people doing on-chain work. Autoglyphs (2019) is one of the original on-chain generative projects—it’s the project Larva Labs notably held on to when they sold CryptoPunks and Meebits. It’s a predecessor to Art Blocks in important ways. Another project I like is Blitmaps (2021), which are pixelated artworks created by a variety of artists. There was an interesting minting process. There was a capped number of possible initial mints, but the ultimate number of possible Blitmaps was higher, because you could pick the base image from a piece that an artist had created, and you could apply the color palette from a Blitmap that a different artist had created. So you could mint a Blitmap using any combination of those two elements, as long as no one else had done it yet. I like that it had this recombinant on-chain aspect. My favorite Blitmap is a reclining nude. It takes a classical subject and pixelates it, renders it in a very old-school computer art color palette.

Translating a piece mentally to the wall of my room is an important test to see how I feel about something. Some might look better on a screen than as a print, which is interesting to think about when collecting. Besides the Perpetua blanket, I have Ben Kovach’s 100 Print (2022), and some Incomplete Control prints. One of the big unlocks for this market would be better digital displays. It’s still kind of a pain right now, but it will be interesting to track over the next five or ten years, as the cost goes down and the quality goes up.

—As told to Brian Droitcour