thefunnyguys

A member explains how the collective’s early interest and success in trading digital sports collectibles opened the door to a new world of generative art appreciation.

With works by figures such as Georg Nees, Eduardo Kac, and Zach Lieberman, the Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection is one of the most significant private collections of art made with computers. For most of the collection’s existence, the “digital” in its name has referred to the process by which the works in it were created rather than their medium; Spalter Digital primarily included plotter drawings and prints. But last year Anne bought her first NFT, and the collection now has a number of digital pieces along with works on paper. Here, Anne—herself an artist, as well as the founder of digital art education programs at Brown University and RISD and author of the widely used textbook The Computer in the Visual Arts (1999)—shares the story of her entry into the NFT space, and talks about some of the works she has discovered there.

In August 2020 I was asked to be on a panel about NFTs and at the time I literally did not know what those letters stood for. So I made one myself, because I wanted to discuss the process with some firsthand knowledge. When I encountered the concept, I went through the same thing that I think everyone does: I wondered why someone would pay money for a jpg that anyone can see and download. Then I learned about how the token is like a certificate of authenticity, and about other benefits of the space, like resale royalties.

I’d always been on Instagram because the traditional art world is there––but I joined Twitter because that’s where the crypto and NFT worlds are, and I got more involved in the community. People started to buy my NFTs, and when you get paid in cryptocurrency, it feels a bit like having fake money. It is real, but you’re more inclined to immediately spend it on stuff. I think a lot of artists buy NFTs with the money they made selling their own. And it becomes addictive.

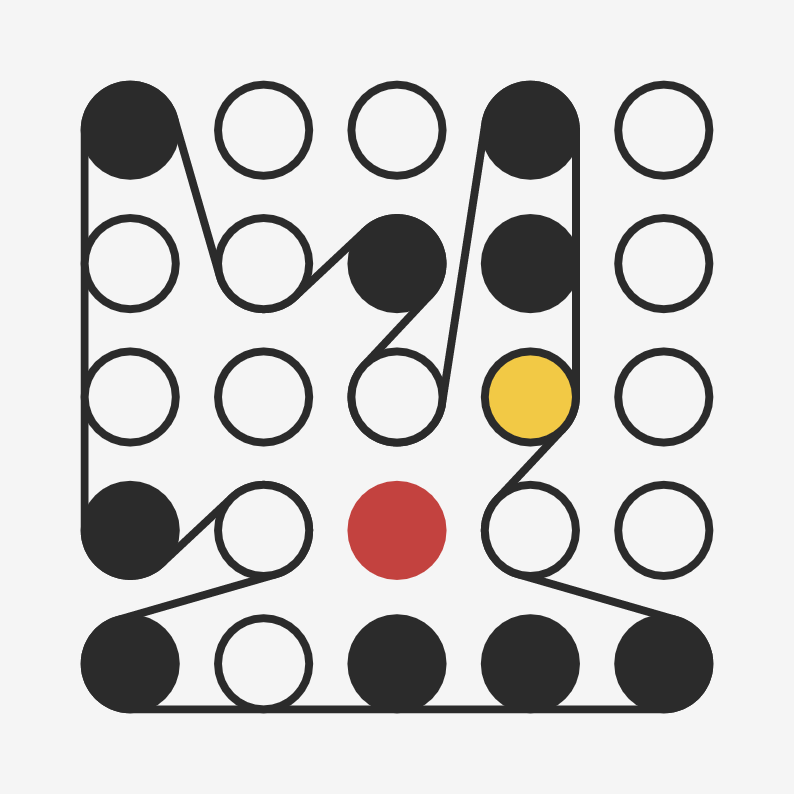

The first NFTs I bought were from Art Blocks, which I encountered through social media. I saw the platform as a direct child of early computer art because of how it used generative algorithms. The NFT sets that Art Blocks offer represent a different way of making art. The early generative artists would create huge numbers of works but then make a selection: for example, you might see three drawings by Manfred Mohr out of the dozens he made. But there are two thousand of Jeff Davis’s Color Studies. To write a piece of code that makes two thousand things that look good is a technical achievement and an aesthetic achievement. I don’t think anything like it has really occurred before. You can have a triptych, where each of the three parts is important both on its own and as a group. But two thousand items—that’s a different order of magnitude, a different beast. One of the first Art Blocks drops I participated in was Ringers by Dmitri Cherniak. I’m honored today to be on the curatorial board of Art Blocks and see amazing new works come through.

One thing I get asked about a lot is the presence of women in digital art and in the NFT world. People say there aren’t many women in the space, but there are. They unfortunately are not regularly included at the highest levels––like in auctions at Sotheby’s or Christie’s––but there are a lot of women making fantastic work out there. I really like Sarah Zucker’s work, which harkens back to early video work: she transfers tape to digital, and keeps the original texture. I enjoy Zucker’s glitchy aesthetic, because most of the work in the NFT space is very shiny stuff, with lots of 3D rendering. Gisel Florez is also a presence in the field. She digitizes beautiful abstract photos that she takes with an analog camera. Her work is all about light and speed and time.

There isn’t any analog painting involved in Watercolor Dreams, by an artist who works under the name Numbers in Motion. But the work has a watercolor effect—the colors seem to bleed out. I really like that because it’s generative but it doesn’t have a lot of hard geometric lines.

Our NFT collection exists in different places: some pieces are on SpalterDigital.com, and then there are the random things that I’ve been collecting in my personal wallet. I have eclectic tastes. Most of what I collected on the Tezos blockchain is just for me. I don’t know if Tezos will even be around in ten years. The works in Spalter Digital tend to be Ethereum based. I collected a number of NFTs on the Hic et Nunc platform, which is now defunct, though you can still see them on hicetnunc.art. Hic et Nunc was a fun place to play. But it was really hard to know who an artist was. If they didn’t have a Twitter handle on their profile you just saw a bunch of letters and numbers. That’s how I found Jess Hewitt—randomly, on Hic et Nunc.

With NFTs, just as with any other art form, Michael and I don’t collect anything that we don’t personally enjoy. We don’t buy stuff to flip it. Our theory is, if it’s not worth anything, we still have artwork that we love. You can’t lose that way. If you buy a lot of stuff and you think you’re going to sell it for more money—that’s like going to Vegas. I wouldn’t say with absolute certainty that I would never sell any NFTs from the collection. If I bought an NFT for 0.25 ETH and can sell it for a million dollars and buy more art—that’s not out of the question. But there’s no plan to do so right now.

— As told to Brian Droitcour