Avatar as Subject, Artist as Avatar

Two exhibitions that engage with the trendy notion of “worldbuilding” offer different visions of what the role of audiences in artist-conceived worlds can be.

At the Global Art Forum in Dubai last month, I moderated a conversation with Ahaad Alamoudi, a young artist from Saudi Arabia. Instead of the usual slideshow, she presented her work as a two-channel video. One played a selection of her work, while the other, at the edge of the screen, showed “Future Ahaad,” the artist’s own face seen through TikTok’s Bold Glamour filter, dewy and smiling. “A vision has been sold to you and you’ve been given a deadline of approximately twelve years for the overall vision to come into fruition,” Future Ahaad said. “But all these visions are not your vision, so how do you begin to navigate your existence?” It was an implicit comment on Vision 2030, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to diversify Saudi Arabia’s oil-based economy through a series of socioeconomic reforms. A key part of this strategy has been cultural, as the government spends billions on ambitious public art (more than 120 installations lit up the capital in this year’s edition of the annual light art festival Noor Riyadh), two alternating biennials (Diriyah Biennale and the Islamic Arts Biennale), and dozens of museums.

Alamoudi bears witness to the radical changes in her formerly isolated cultural environment. The Message Has Been Sent (2018) indexes this moment of transition. Multiple arrangements of horizontal and vertical screens reflect a flurry of movement across varying scales. There are crowds at stadiums alongside slower takes of Roman statues and clips from the Wildcat comic translated into Arabic, as well as documentation of a public race of women cyclists and an emergency hotline that includes women as responders for the first time. In this and other works, Alamoudi sheds light on the fact that Saudi youth have long been connected to the rest of the world through the internet. “I learned a lot in digital space and started using the language of the internet in my work,” Alamoudi told me. “This enabled me to navigate my social environment beyond the surface of things.” Her work deconstructs national and cultural symbols, such as folkloric dance, falconry, and popular songs. Through the use of digital manipulation to speed up or slow down found footage and replicate images, she references a Saudi youth culture of viral remixes, adding new layers of interpretation and play.

Alamoudi is interested in how the dialectic between popular media and secrecy has played out in Saudi culture.

I first encountered Alamoudi’s work at the fifth edition of the annual exhibition “21,39” in Jeddah, where a screen playing her work Those Who Don’t Know Falcons Grill Them (2018) sat atop a heap of earth. In the seductively slow video, men perform a traditional war dance from the west of Saudi Arabia, now seen primarily at weddings across the country. The screen splits horizontally, disrupting the image and serving close-ups of various movements: shoes dig into the ground, releasing clouds of sand; hands whirl long sabres. As the performers fling themselves in the air, it’s impossible to miss the print on their clothing: wide-eyed falcons, endlessly repeated. The choreography exaggerates and distorts the image of the falcon, which is common in Saudi iconography. The use of the falcon here—as a textile pattern marking and multiplying a national symbol—is typical of Alamoudi’s treatment of images as representations of representations.

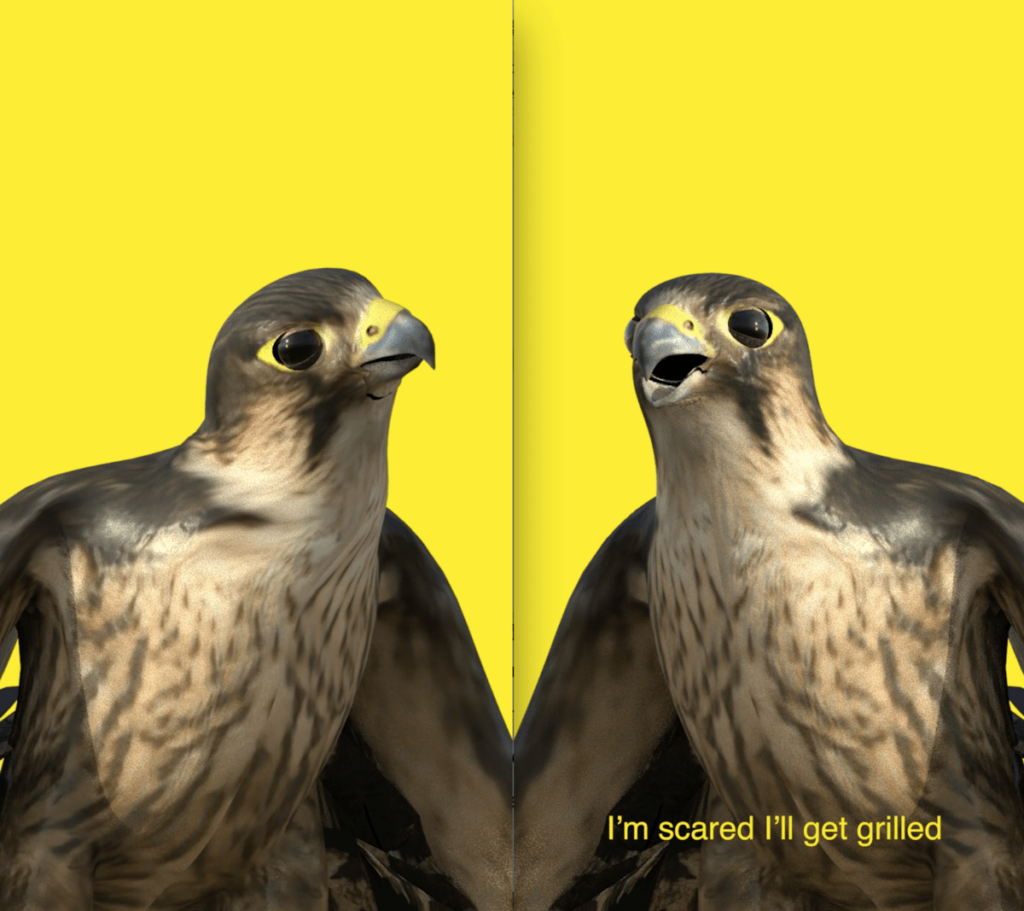

Elsewhere in her work, the falcon takes on different forms and characters; the national emblem becomes a multi-faceted construct. In What is This? (2019), two 3D renders of falcons banter about the chaos around them in a way that’s hard for the viewer to understand, as if the birds are speaking in a coded language full of in-jokes, the way men might share secrets in a private space. Alamoudi is interested in the ways in which this dialectic between popular media and secrecy has played out in Saudi culture. Back in 2013, the song “Tini Warwar” was a hit in the country’s underground circles. Tini means “give me,” while warwar is a nonsense word. The song’s beginning samples Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry,” probably a nod to the contemporaneous viral video “No Woman, No Drive,” a satire of the prohibition on Saudi women operating vehicles (which has since been lifted). Alamoudi’s v=YGvLDDWwLEk (2016) restages the “Tini Warwar” video, with the artwork’s title quoting the YouTube url. Her subtitles annotate the meaning of warwar as “money, a gun, or something fast.” The performer, armed with a gold sword and wearing a car-print tunic, sings: “My master wears a wig and I am bald, why. My master rides a Roll-Royce and I a Honda, why….” He stands in a car scrapyard, and an animated overlay surrounds him with floating rows of sticker-like icons: Marley’s head, cars, blond wigs, cans of Red Bull and Coca Cola. They descend vertically, stretching like viscous fluid.

Her extrapolations from a 3D textile to a 2D video then back to a 3D sculpture reflect an iterative, unstable present.

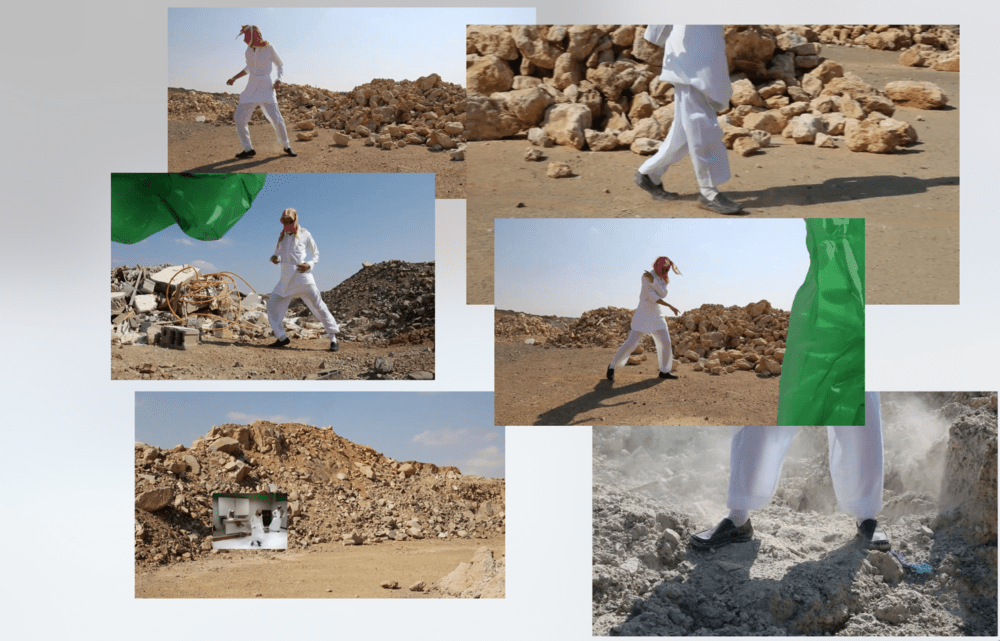

v=X7czOWj2Bf4 (2016) is another adaptation of a viral video. In this case Alamoudi uses the original footage—of Saudi men imitating Michael Jackson’s footwork—as insets in her own shots of a construction site with the uncanny appearance of a faux desert, which is also interrupted by blown-up images of squashed green plastic bottles she found on location. The sonic landscape alternates between recorded song, the shifting rocks on the ground, a murmur of Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal,” and Alamoudi’s own poetry in Arabic about witnessing and unknowability. She ends with a dose of romanticism—a line that can be translated either as “you are the moon” or “you are beauty.” Alamoudi weaves literary registers with satire and popular culture. But like her favored format, the music video, her language— juxtaposing poetry with pop—is accessible. Using vernacular modes of expression from contemporary digital culture, she amplifies the online circulation and manipulation of text and image.

She also comments on the loss of meaning via free-flowing internet languages. In Self-Portrait as a Pomegranate (2017), a man wearing a luscious pomegranate thobe against a blood-orange backdrop is presented both as an orator and a mocking joker. On one channel, he recites lyrics from the 1960s Kuwaiti song “O Pomegranate,” a lover’s lament. On the other, he says little but gestures effusively, an antithesis to the orator. In the work’s install, the pomegranates printed on the man’s robe become motorized objects, twirling on the ground. “Video feels like a print to me,” Alamoudi said in our interview. Her extrapolations from a 3D textile to a 2D video then back to a 3D sculpture reflect an iterative, unstable present that is likewise subject to edits, modifications, and repetitions. She performs these different states of being with her own body as well. The Three (2021) features a trio of Alamoudis, each presenting opposing perspectives toward a cultural shift. As she lip syncs a poem read in a man’s voice, the silvery sea backdrop appears in her mouth with an eerie, mercurial transparency. “I’m interested in mimicry,” she explained, “and how far you can go while still being who you are.”

Future Ahaad, Alamoudi’s companion at the Global Art Forum, encapsulates this vision. As she performed the entanglement between individual and collective identities, between self and state, flesh and filter, what came across most strongly was not the simulation of an avatar, but rather a twofold exercise in seeing—an observation of those who are doing the watching. Present Ahaad seemed to ask: what are the ways of stepping forward to look upon an immersive cultural moment as an archive from the future, instead of the past? And how can the nostalgic languages of song, poetry, and popular culture, carried over into the present, capture that ungraspable shift in hybrid, mediated forms?

Nadine Khalil is an editor, curator, and art writer based in Dubai.