The Hirsch Truth: Episode 1

A video critique of PFP projects World of Women and Milady Maker, plus works by Katherine Frazier and Sara Ludy.

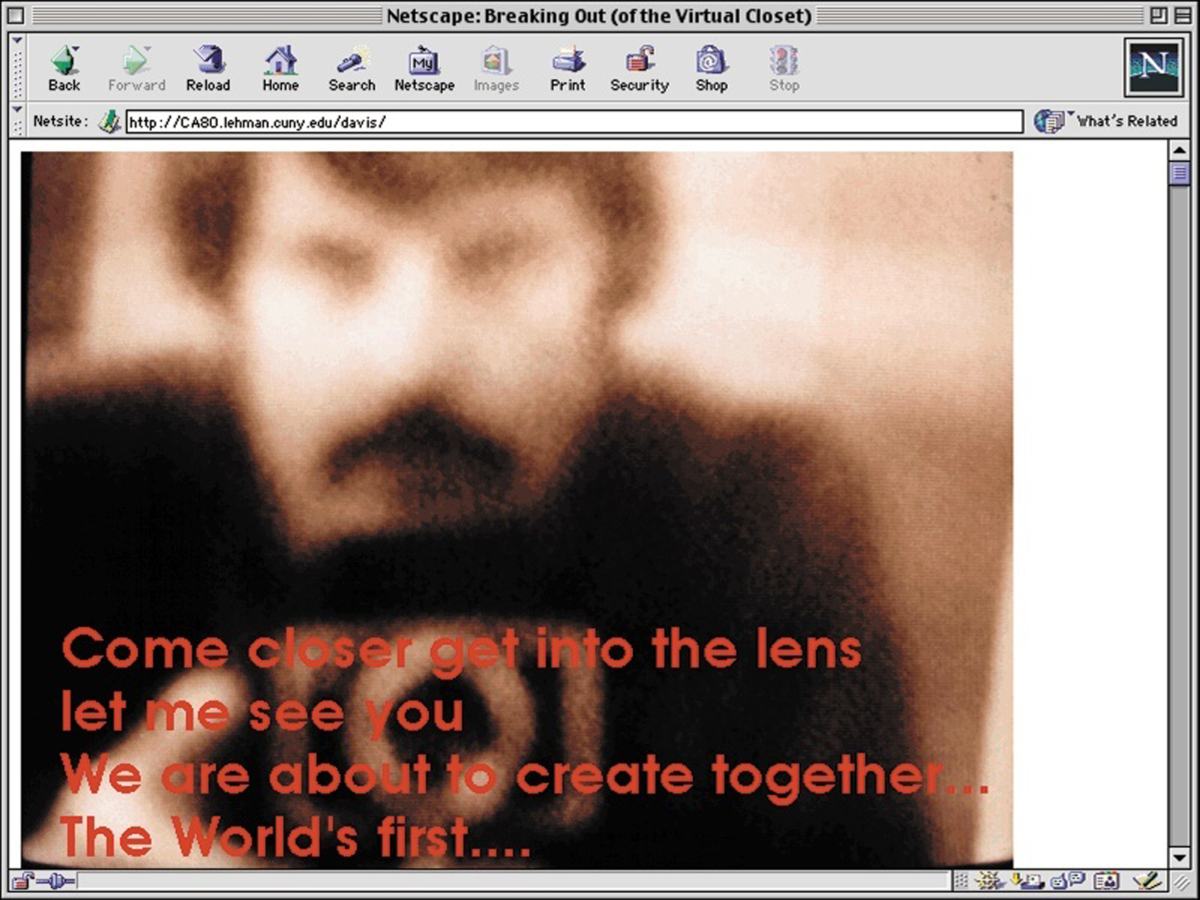

Begun in 1994 by Douglas Davis, The World’s First Collaborative Sentence opens with an expression of early web optimism, espousing in caps our closeness despite being “THOUSANDS OF MILES APART.” At the time of writing, the sentence lingers indefinitely on “hi im colin,” which may be its final words. Restored by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 2012, it ran to 104 consecutive web pages of text, featuring somewhere over a million words—until, at an undisclosed moment, contributions to the sentence were disabled, making “colin” an unknowable figure and de facto period.

Originally commissioned by New York’s Lehman College Art Gallery for an exhibition, the sentence as an artwork is authored by Davis, with programming by Gary Welz and Robert Schneider, but over time its massively communal nature has rendered such attributions obsolete. Reflecting the aspirations of the early web, the sentence stems from humanity at large. It is neither governed by a single authority nor divided into corporate terrains, and blends a potent mix of the “debasing to the angelic,” to borrow a phrase from John P. Barlow’s 1996 “Declaration of Independence in Cyberspace.”

Rejecting notions of individual creative autonomy, a recurrent type of massively collaborative internet artwork transforms the webpage into a canvas.

During the Web 1.0 and early Web 2.0 eras of the internet, the networked practices of Davis and other net artists tested the potential for ludic collaboration and distributed creativity, and disputed notions of singular authorship and virtual property rights. Importantly, access to these creative venues was open and unrestricted by capitalist motives, in opposition to the territorial divisions being established by then-nascent metaverses such as ActiveWorlds and Second Life. By returning now to consider the open-data systems crafted in this period, we can reflect on how the egalitarian creative potential of these early net art projects might be resurfaced in the era of web3.

Rejecting notions of individual creative autonomy, a recurrent type of massively collaborative internet artwork transforms the webpage into a canvas, on which visitors are invited to overwrite, extend, or amend portions of the overall composition. Andy Deck’s Glyphiti (2001) is a distributed public artwork that marks and records alterations in real-time, transmitting updates to any users who are currently visiting the site. Composed of editable glyphs—pixel art squares reminiscent of Egyptian hieroglyphs—the platform was the first of a series that Deck developed. The same year, he launched Collabyrinth, adding a third dimension and color to oddly evoke the Window 3D Maze screensaver. A later project, Screening Circle (2006), adapted the practices of quilting bees to alter the frames of a communal animation.

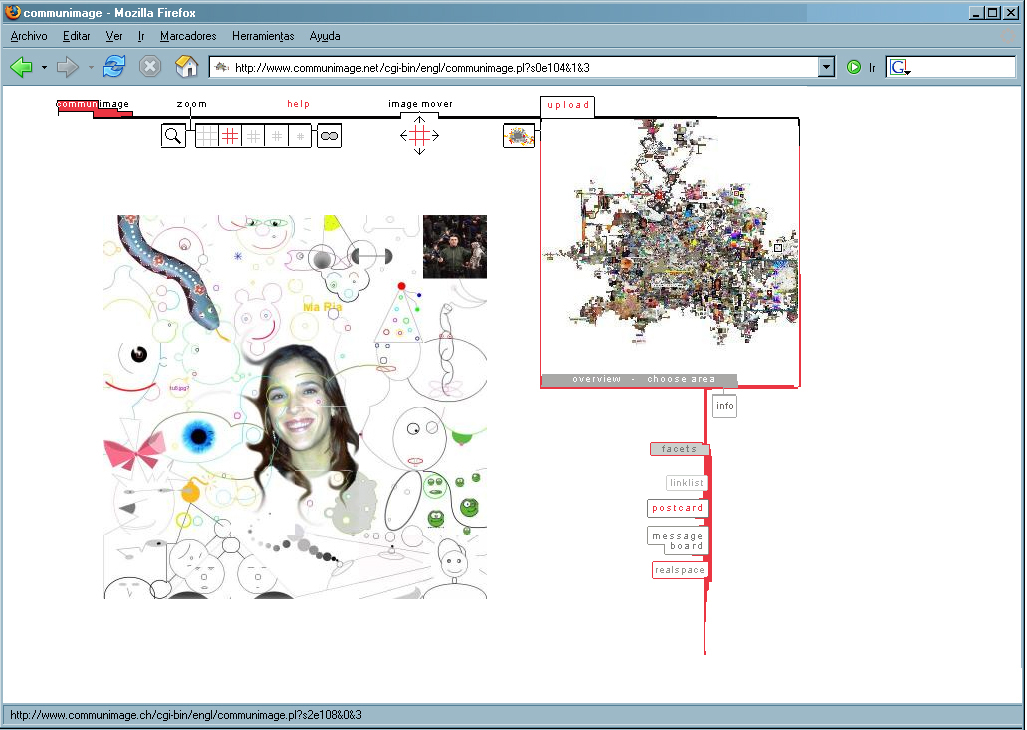

Adjacent to Deck’s work, Communimage by the coding collective calc and Johannes Gees has been running since 1999 and still receives regular updates (it is now in the collection of HEK in Basel). Composed piece by piece from patches 128 pixels square, the work is made up of 26,000 individual images. Using a bespoke interface, users can navigate up, down, left, and right, cycle through varying levels of zoom, and find unclaimed spaces to upload their contributions. Viewed in its entirety through a pop-out function, Communimage tells many stories of individual and group endeavor. A huge field of pixels represents a single eye; Swiss flags repeat; web URLs are spelt out across horizontal portions.

In these projects, the canvas becomes an arena of play. In the case of Communimage, applied images are fixed and so the game becomes a territorial rush to colonize the mapped landscape, while the palimpsests of Glyphiti and Screening Circle suggest a more perpetual endeavor. For players of these artistic games, the experience differs in relation to their rate-of-return; more frequent visits will reveal the strata of recontextualization. Those who only foray back occasionally will be presented with entirely “new” compositions, their contributions long ago consumed. The game continues as long as there is a single player on the pitch.

Going beyond questions of creative autonomy, Mark Napier’s multi-user browser Riot (1999) demonstrates the porous boundaries of the internet, dissecting and recombining components of the last three web pages visited by anyone surfing with the software. A reference to the state-enforced gentrification that took place in New York’s East Village in the 1980s, Riot breaches the boundaries of corporate enclaves, overlapping CNN.com with whitehouse.gov and Vatican.org. The aesthetic incoherence combined with the perpetual interference of other users’ URLs turns Riot into a lucid illustration of William Gibson’s definition of cyberspace as “a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators.”

An expansion of the tracking capabilities suggested by Napier’s work, QQQ by Tom Betts (aka Nullpointer) is a Quake III Arena mod artwork launched in 2002. Akin to the aesthetic recompositions of Riot, Bett’s programme recasts the actions of Quake III Arena players into an abstract image and audio stream. Via QQQ, modes of play in the multiplayer first-person-shooter game become the underlying toolset of an alternate spectator mode that renders movement, missiles, and kills into a fluctuating abstraction. Building upon precedents set by mod-making artists such as JODI, QQQ effectively reconfigured the language of battle into a series of graphical paintbrushes, layering onto the arena a secondary system that is judged on painterly terms instead of gaming achievements such as kill streaks.

Admittedly, across these quasi-game artworks the cumulative or concurrent number of visitors pales in comparison to the active players of MMOPRGs such as World of Warcraft (2004), EVE Online (2003), or Final Fantasy XI and XIV (2002 and 2010). Despite this difference, the artworks and games share certain properties of communal activity, collective navigation and shaping the world together in-real-time. What we could call massively multiplayer online art-playing games are defined by a strong ethos of play, with each artwork serving as a foundational board and ruleset rolled into one, while also being the perpetual result of the game taking place within it.

Looking back at these projects can help us to imagine a future for the web in which players are welcome to create and destroy in equal measure.

Such works can be understood as the result of unnamed individuals taking agency in their everyday internet actions. Their contributions to the communal artwork, no matter their individual motivations, function as a reflection of the society they inhabit. Citizens can proactively work alongside one another, or they can outmaneuver and disrupt by placing glyphs in the way of emergent designs. They can add beautiful sentiments to an unfolding sentence or fill it with line upon line of hate speech. As such, to act in these types of space means to accept a level of disorder and degree of impermanence. Looking back at these projects can help us to imagine a future for the web in which players are welcome to create and destroy in equal measure, in which territory is not controlled by commerce but by activity, and in which the weighty shackles of record-keeping are broken, allowing for more anarchic agility.

Elliott Burns is co-founder of the online curatorial platform Off Site Project.