UnicornDAO

The DAO prioritizes collecting NFTs connected to performances and political actions by women and nonbinary artists.

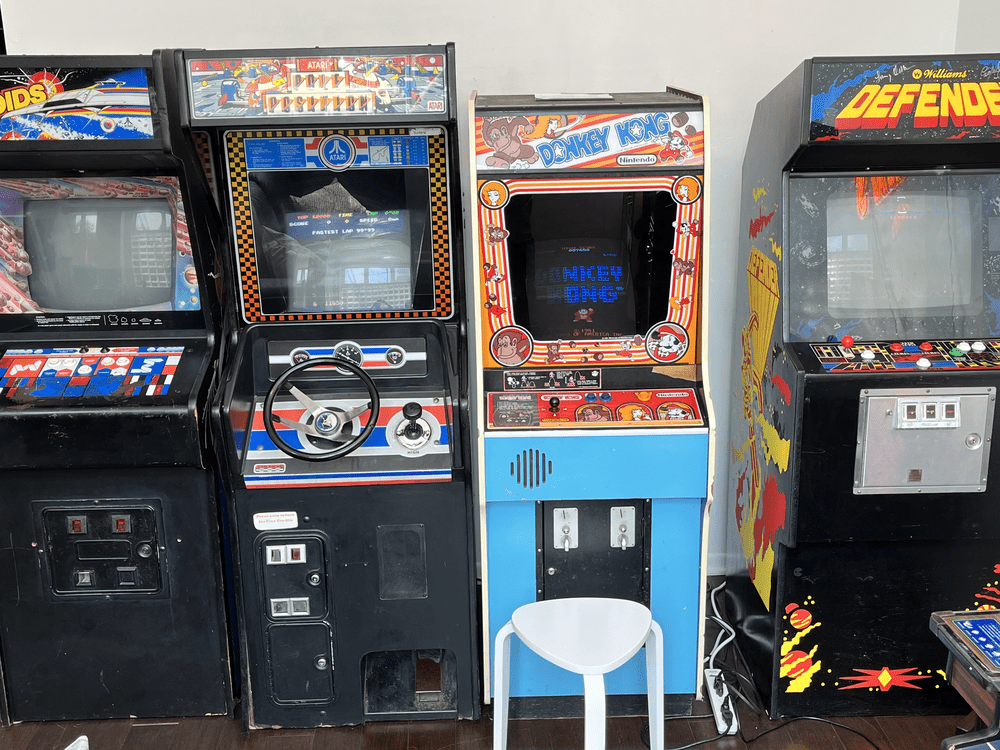

What does it take to present the history of video games? There are several institutions around the world that approach this question from various directions. Chicago Gamespace, which opened its doors in September 2020, aims toward a comprehensive populist history. The museum showcases the most widespread games made for computers, consoles, and arcades since 1970s in playable format. Some are displayed on emulators—contemporary devices that mimic the interface of the game when it first came out—but most are shown on the original hardware, which in the case of arcade games means the bulky, colorful cabinets that house the machine and its controls. In addition to this permanent exhibition, Gamespace hosts temporary shows delving into the history of particular games or themes in game history. Jonathan Kinkley, Gamespace’s founder, was previously a director at VGA Gallery, a nonprofit space for new media art, and has held development positions at several museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago. He spoke to Outland about Gamespace’s principles and plans for the future.

Gamespace’s collection is unique in that it’s a curated collection comprised of the most important and influential games from history. That is a somewhat subjective characterization, but we consider objective metrics like the sheer quantity of copies sold and played. We also ask: is the game timeless? Does it look bizarre from a contemporary perspective?

The collection begins with Spacewar (1962), the first true video game, and includes some of the better-known early games, like Space Invaders (1978), Pac-Man (1980), and Donkey Kong (1981). It goes up to Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998). It is curated by myself with assistance from Ethan Johnson and Tim Lapetino. We don’t want to collect games made after 2000, to give ourselves critical distance. A new title might seem like the best game of all time, but then five years pass and no one thinks about it or plays it.

For about 75 percent of the games in the collection we have the original consoles and hardware. In some cases we use an emulator. I’m desperately looking for an original Pong cabinet from 1972, since that was what started the arcade revolution. But until I get my hands on that piece of video game history we’ll use an emulator. I do have the original Home Pong (1975), the first game that could be played on a television at home.

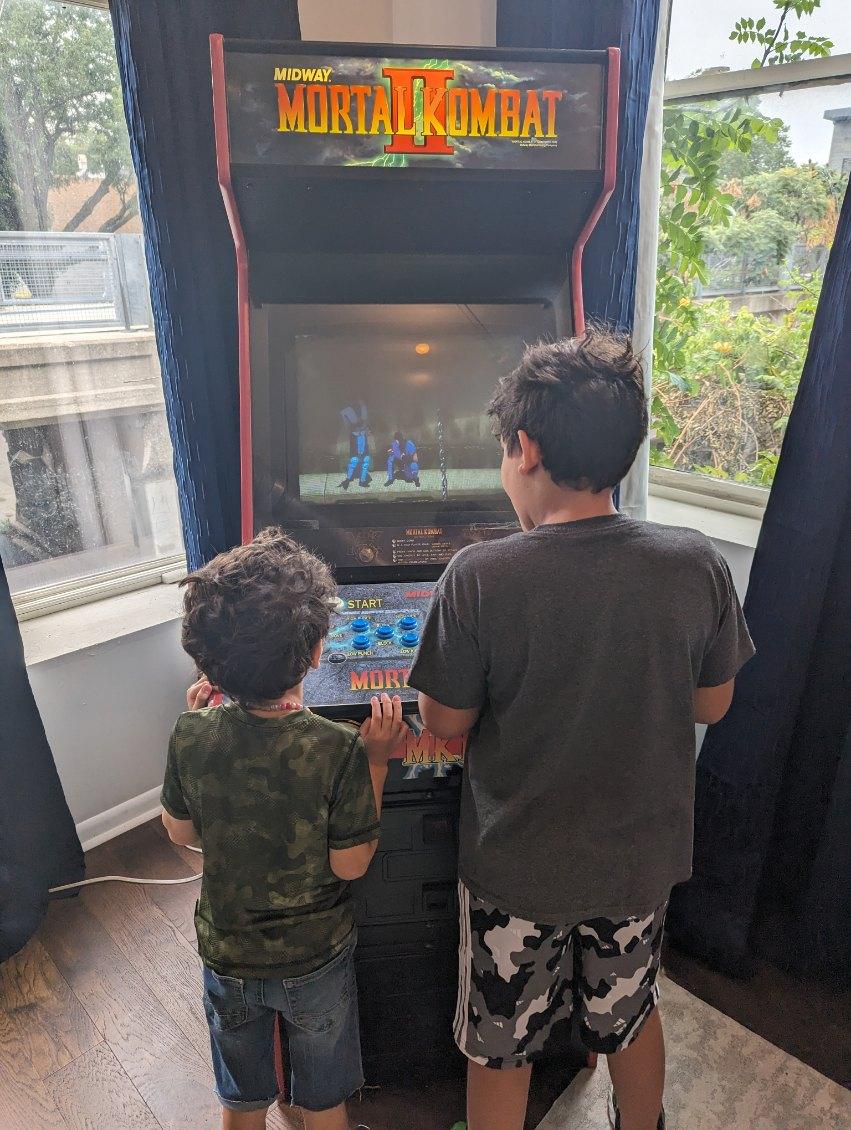

Jim Zespy of Logan Arcade, a bar with vintage games, is very helpful and supportive. He’s got an amazing collection, and loans games to us regularly. Patrick McCarron is another key figure in the video game scene here in Chicago. He lent us his arcade cabinet for Mortal Kombat II (1992), and others have donated games and artifacts. We’ve got boxes and boxes of Nintendo Power magazine from Devin Winklemann, which people can peruse in our library space. We also have some historic consoles, like a Bally Astrocade from artist jonCates, and a Magnavox Odyssey, that have been donated to us.

Whereas most museums have 99 percent of their collection off view, we have 95 percent on view. As Gamespace grows we’ll strive to maintain that ratio, both for ourselves and also for the collectors who are so generous in lending or donating work. We want the games in our collection to be played, and if a game doesn’t fit into the narrative of game history as we’re telling it, then we’re not able to accept it.

Our collection works on multiple levels. Adults remember the games that they played when they were young. Though the kids who come here probably never played Pac-Man in its original form, they might have played another version at Chuck E. Cheese or someplace like that. The awareness that kids have of the older titles is amazing. They also interact so intuitively with these games. Kids don’t approach games with the same trepidation as adults. They’re not as worried about dying quickly.

Wherever possible we try to display the game that people are going to be the most familiar with. We did a Q*bert show with Atari and Nintendo versions of Q*bert, which were the most widely played at-home games, even though versions were produced for more esoteric consoles. We select the ones that people can jump into and get involved with.

Most arcade games were only designed to last for a few years. But they were made in the 1970s and ’80s, the era of great American manufacturing, many of them here in Chicago by Williams Electronic Games and Bally Midway. They hold up really well. That said, they are very old machines and they break down all the time. We have some regular reliable support in that area. Just this week, one of our repair techs Robbie Komen came in because the acceleration pedal on Pole Position (1982) was not accelerating. He also fixed a graphics display issue we were having with our Q*bert (1982) cabinet. Skip Hansen from Coin-Op Services in Elk Grove Village managed to get the boards working on our loaned Discs of Tron (1983) for “Light Cycles: 40 Years of Tron and Games,” the exhibition we had last spring. Dave Vondle is working on the crowbar circuit for our Magnavox Odyssey. We’re very lucky to have this network of experts, but they’re a dying breed.

Broadly speaking, we share an approach to conservation with a lot of great art museums. Any interventions or preservation techniques we use are reversible, and we document them. Maybe someday a better technique will come along, so we need to be able to undo what we’ve done in order to use the new technique. As for other best practices, we try to maintain the right humidity and temperature conditions. When we clean the games we use acid- and alcohol-free cleaning materials so that we are not damaging the paint or the hardware.

My background is in art museums. That’s the model that I’m most familiar with, and the one Gamespace is based on—the permanent collection, a rotating exhibition space, a shop area, and a library. Eventually I’d like to have café. It would be wonderful to keep expanding following that model.

I’ve also been traveling the world looking at other game museums: the Computerspielemuseum in Berlin; the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York; the National Videogame Museum, which has sites in Sheffield, UK, and Frisco, Texas. I’m proud that we have a bit of contrast with those other institutions. In many of those museums you can’t identify an obvious rationale behind the selection of games on view. Some feature rare, esoteric games. That’s fine, but we want visitors to be able to play through video game history. Our audience can experience emulations of early games like Colossal Cave Adventure (1976), arcade games, and a Nintendo console with Super Mario Bros and Duck Hunt (1985). We’re about games writ large, not just arcade, console, or PC.

It would be nice one day to have a section that presents Chicago’s contributions to video games during the golden era of arcade and pinball. We’re already focused on a particular medium—games—and I don’t see groupings by genre in the future, but I wouldn’t rule it out. We have an exhibition coming up on vector graphic games, which did not use pixels as most games did. We’re just trying to remain nimble and flexible as an organization. We’re early in our life and we’re really excited to be at this place of momentum and growth and we look forward to expanding further.

—as told to Brian Droitcour