Style over Substance

To situate early computer art in familiar narratives of abstraction and minimalism, an exhibition rewrites history by separating social concerns from formal ones.

It takes a newspaper at least a day to make sense of what’s happening. It takes a book much longer. It has been more than a year since the NFT boom of 2021, and we’re bound to see a spate of books dissecting that phenomenon. Surfing with Satoshi: Art, Blockchain, and NFTs by critic and curator Domenico Quaranta was published in Italian improbably early, in the summer of 2021. Now it is available in an English translation published by Ljubljana’s Aksioma Institute for Contemporary Art. Quaranta’s account, which addresses the rise of NFTs and the connections between artists’ recent use of blockchains and historical interventions into art markets, sets a high bar for others that will follow.

So far Surfing with Satoshi is the only book of its kind: an attempt by a single author to weave a motley array of histories—of art movements, markets, technologies, and critiques—into a coherent narrative. Other books on art and crypto are polyphonic. Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain (2017), published by London art-and-tech organization Furtherfield, is an essential tome, especially as a timestamped record of what the field looked like before the popularization of NFTs. It’s a collection of essays and expository pieces about artists’ projects—not the sort of thing you’d read from cover to cover, as it lacks the synthesizing view that Quaranta provides.

Quaranta’s account sets a high bar for others that will follow.

A more recent comparable volume might be the catalogue for “Proof of Art,” an exhibition held last year at the Francisco Carolinum in Linz, Austria. That show is notable as the first museum exhibition to respond to the NFT market (distinguishing it from exhibitions at the ZKM Karlsruhe explaining crypto for its audiences), and the accompanying book contains essays and entries on artworks. In “Proof of Art,” curator Jesse Damiani projected the narrative of NFTs into the past, naming works by Herbert W. Franke, Nam June Paik, and other artists as precedents. The selection was limited by what could be available to display at the Francisco Carolinum. Without the responsibilities of exhibition-making, Quaranta’s approach is more flexible and far-reaching. His book’s greatest strength is the persuasiveness of his links between blockchain-based art and twentieth-century conceptualism. The historical orientation of Surfing with Satoshi is what makes it durable, despite being written in response to—and during—a specific moment. One thing that doesn’t hold up is the misgendering of artist and theorist Rhea Myers. This was a serious error when the book was first published, and it’s baffling that it wasn’t corrected in translation. The choice to misrepresent the identity of a leading figure in the field tarnishes the relevance of an otherwise good book.

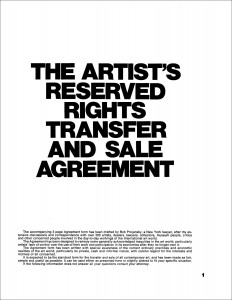

Quaranta takes an agnostic approach to the blockchain, giving space to critiques of its drawbacks while acknowledging its potential. But he is steadfast in his advocacy of new media art. His main objective for much of the book seems to be legitimizing recent works by emerging and mid-career artists by contextualizing them in relation to established histories—demonstrating their cultural value regardless of their price on the NFT market. His account includes chestnuts that anyone who was reading art critics’ attempts to make sense of NFTs in 2021 will remember. Quaranta cites Marcel Duchamp’s 1924 Monte Carlo Bonds as an example of speculation commenting on how artists create value; the certificates of authenticity for Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings as an analog for generative NFTs that include instructions for producing the work along with the means of its verification; and Seth Siegelaub’s contracts, which attempted to enshrine artist royalties long before that practice was introduced to NFTs by the digital drawing club Dada NYC. But Quaranta adds depth to these familiar examples with other, lesser-known nuggets of information. Before the Monte Carlo Bonds, which licensed Duchamp to gamble with collectors’ money, he forged a check to a dentist. While not as flashy or glamorous as a visit to the casinos of Monte Carlo, this was a bolder, more criminal assertion of the possibility of manufacturing monetary value through artistic skill alone. (When the check later sold as an artwork, the dentist was finally paid, with interest, for his services.)

Quaranta introduces LeWitt’s intervention into matters of reproducibility and authenticity by recounting the details of 2012 lawsuit against a gallery that lost a consigned certificate for a LeWitt wall drawing—an anecdote that acutely frames the problem of a work that cannot exist without its authenticating mechanism. In his discussion of Siegelaub’s contract, Quaranta draws an interesting contrast between the 1970s art world, where relationships among artists, dealers, and collectors were chummy and familial, and the more impersonal, global art market of today, where the digital automation of royalties may be a necessary condition in artists’ financial well-being.

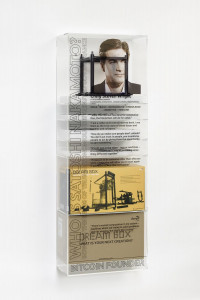

When it comes to living artists, Quaranta enriches his discussion of their blockchain projects by citing earlier works to demonstrate how these figures have been making work about the impact of networked technologies on notions of value and audience for a long time. Jonas Lund’s eponymous token JLT (2018), which enables holders to make decisions about the direction of his career, is often cited as an important blockchain-based artwork preceding the NFT boom. But Quaranta also mentions Lund’s Flip City (2014), a series of zombie formalist abstract paintings with GPS trackers attached to the canvas, transmitting the current location of each work to a database that records and displays the history of transfers—essentially, a physicalized NFT avant la lettre. The artist’s Critical Mass (2017) broadcast a live feed of his studio and invited online viewers to dictate the actions of the artist and his assistants, experimenting with DAO mechanics of community influence a year before JLT was launched. Quaranta also shows how the projects Simon Denny has undertaken as an artist and curator to explore the ramifications of blockchain technologies are rooted in practices of juxtaposing disparate visual vocabularies—of games, trade fairs, Powerpoint presentations, and conceptual art—to approach a topic from multiple angles. Denny tries to get the truth of a thing by speaking its own language, and other languages adjacent to it.

You can almost feel him inserting new material hot off the digital presses to represent more fully what was happening.

The second and third chapters, on blockchain-based art and its conceptual precedents, are the strongest parts of Surfing with Satoshi. The fourth and fifth chapters address NFTs made by artists who, unlike Lund and Denny, lack art world credentials, as well as the platforms their work is sold on and media coverage of the market explosion. Here his agenda seems to be to present a neutral document of a history that is still taking shape rather than to write a history from his own perspective. Quaranta doesn’t champion any unsung crypto artists. The ones he discusses are the best-known, most financially successful—Beeple, Pak, Mad Dog Jones, Fewocious—thus inadvertently lending credence to the belief commonly espoused by NFT investors that market value and cultural value are one and the same. His approach to the debates about the value and utility of NFTs for art is to represent both sides even-handedly, which makes the chapter useful as an artifact of 2021, if not a gripping read in its own right. He quotes heavily from the avalanche of thinkpieces published in the winter and spring of 2021 (including several I wrote for Art in America), and you can almost feel him copying and pasting text, moving paragraphs around, inserting new material hot off the digital presses to represent more fully what was happening.

Quaranta’s moderate stance is one shared by many of us who have been paying attention to media art for some time and hope that the creation of a digitally native market for this work might solidify its institutional standing, in spite of all the flaws this market may have. Technology is not neutral, Quaranta acknowledges, but he smartly insists that this does not necessarily mean it is evil—just that its social valence is ultimately determined by who uses it, and how. The implicit argument of his book is that if we are to make web3 hospitable and healthy, for artists and everyone else, we can do so by surfing with Satoshi—by riding the wave and steering to stay on top of it, so as not to get swept away.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.