Magic at the End of the World

Crisiscore is a curatorial practice that traverses physical and virtual spaces, seeking the sublime in precarity and disaster.

In a time when images can be made cheaply, immersive stories are the way to build meaningful connections. At least, that’s the conventional wisdom for why the concept of “worldbuilding” has gained traction in the media industry. Marvel heroes and Mattel toys proliferate, spinning out narratives across channels and markets. NFT projects like Omega Runner and Azuki promise that the PFPs they hawk will become characters in games and cartoons. Art-adjacent immersive entertainments like Meow Wolf are conceived as exercises in worldbuilding, with interactive exhibits constructed around fantastic stories that visitors are welcome to learn as much or as little about as they like. But the art world has only gingerly touched this trend. This stems from the differences in the kinds of audiences that museums and mass media aim to cultivate—the viewer seeking enrichment versus the consumer seeking escape. Yet, more and more artists are bridging art and popular media, empowered in part by the digital environments where these spheres bleed into each other. What seems most interesting about such crossover projects is not worldbuilding as such but the position of the audience and how it’s changing as artists incorporate more elements of interactivity, participation, and collaboration into their work.

If mass-market games foreground conflict and struggle, art games are more about exploration and contemplation.

This summer, two exhibitions with “worldbuilding” in their titles have offered distinct visions of what that term can mean and what artists can do with it. “Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age,” curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, opened at the Julia Stoschek Foundation in Dusseldorf in June 2022 and remains on view there through December 10; this past June the show opened in a second venue, the Center Pompidou-Metz, where it runs through January 15, 2024. Obrist often speaks of his fascination with games as the most popular media form of the twenty-first century. His exhibition includes not only artists who have modified existing games and appropriated their visuals, but also those who have mastered widely used engines to build games of their own. “Collective Worldbuilding: Art in the Metaverse,” curated by Sabine Himmelsbach and Boris Magrini, closed this past weekend at HEK in Basel. This exhibition involved elements of play, but focused on web3 mechanics as a means by which artists can grant agency to their fans and make decisions about their work with audience input.

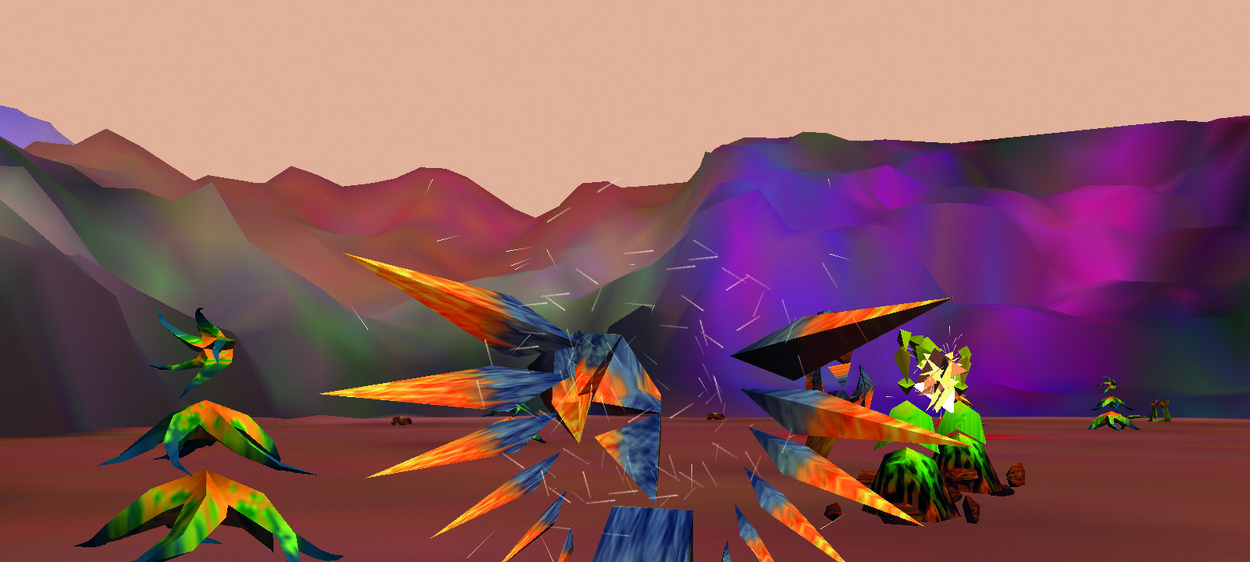

The iteration of “worldbuilding” in Metz features thirty-nine works, about a quarter of which are playable games. If mass-market games foreground conflict and struggle, these art games are more about exploration and contemplation. Lawrence Lek’s Nepenthe Zone (2022) is set in a house by a tropical lagoon, cast in shades of blue and violet. In this meditative setting there’s little for a player to do but wander and ponder. H.O.R.I.Z.O.N. (Habitat One: Regenerative Interactive Zone of Nurture), 2021, by the Institute of Queer Ecology, gives you tasks to accomplish, like gathering plants in the forest to prepare food. But there are no dangers or challenges in the game world’s collaborative utopia. To make The Bush Soul #3 (1989), Rebecca Allen, a pioneer of 3D graphics, used early AI software to enable emergent behavior from the plants and animals as they respond to player actions. The expressive simplicity of the imagery is beautiful, but this game, too, offers little more than an environment to discover. Suzanne Treister’s No Other Symptoms: Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky (1995–99), originally released as a CD-Rom, is series of static scenes that the player clicks through to find the protagonist’s recipes and notes on analysis sessions with Freud. Compelling in its weirdness, the game leaves you wondering where the fictional biography of Brodsky (Treister’s alter ego) meets up with reality and where it diverges. Most of the games in “worldbuilding” are not fun per se, but they give the player something to think about. In this regard Treister’s is the most generous.

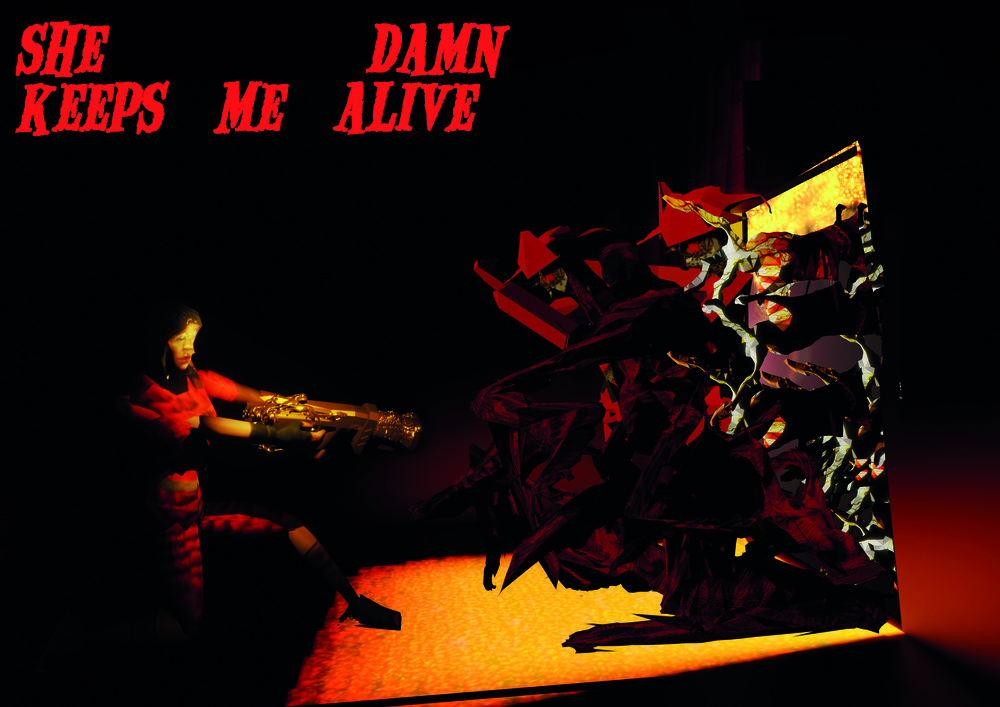

You’re given a handheld plastic gun to play Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s She Keeps Me Damn Alive (2021), but firing it at the screen risks triggering a dire, disapproving message: you hurt Black trans women—game over. As you move through the game, you encounter crowds of polygonal, semi-abstract figures. Some represent Black trans women and others are enemies. You can’t tell who’s who without meticulous study of the game’s taxonomy, and the character design isn’t all that varied, so most attempts will end in failure. Brathwaite-Shirley’s intervention reminds me of Power Kill, a 1999 “metagame” by John Tynes, intended to be used as a sort of framing device for sessions of tabletop role-playing games like Dungeon & Dragons. Participants begin by devising characters who live in our world and who have committed murder and larceny. Then, the gaming session continues as planned. After it wraps up, Power Kill resumes. The players inhabit their secondary characters, who have been incarcerated at an institution for the criminally insane. The dungeon crawl they just acted out is recast as a psychotic episode; the orcs and goblins they killed for gold were in fact inhabitants of a public housing complex. Power Kill draws attention to the fact that RPGs normalize and reward vigilante violence. It doesn’t prescribe any correctives to this situation. It just asks players to think about why the simulation of violence feels “fun.” Brathwaite-Shirley’s game—indeed, almost all the works in “Worldbuilding”—can similarly be conceived as metagames. They aren’t that entertaining to play. Instead they prompt reflection on concepts of immersion and play—what it means to briefly take on a new identity via an avatar and test it out by exploring the game world.

“Collective Worldbuilding” at HEK presented the titular concept not so much as a matter of form than as a shared activity, one with the potential to fuel an expanded sense of selfhood. It included video and animation works that reflect on this topic, as well as non-participatory presentations of projects designed to encourage audience agency. Ian Cheng’s Life After Bob (2021) is a half-hour animated film with coded elements that slightly modify its contents on each playthrough, telling the story of an experimental AI implant. A girl named Chalice is merged at birth with BOB, a snakelike artificial life form, and loses her childhood and adolescence to a “tutorial” that teaches her how to embody superintelligence. The implant is a corporate product, engineered by her father, and she emerges from the tutorial into her wedding, a brand event. Life After BOB is a cleverly conceived science fiction, based on the hard-eyed insight that experiments with artificial intelligence and bodily augmentation are driven by capital, and their future can be understood as an extension of the Web 2.0 imperative to brand and market the self, to open it to corporate data harvesting. In Cheng’s animation, bodies ripple, their boundaries shimmer and become porous, as if the soul and artificial versions of it bulge outward from the self. There’s a similar effect in Dorota Gawęda and Eglė Kulbokaitė’s haunting video Mouthless Part III (2023), an entry in a series of works inspired by Slavic mythology. This one takes place in a rye field at noon, where a peasant encounters a demon whose body shifts and expands, tempting the peasant with the possibility to do the same.

“Collective Worldbuilding” presented the titular concept not so much as a matter of form than as a shared activity with the potential to fuel an expanded sense of selfhood.

The visual metaphors in these fictional representations of augmented bodies primed viewers for the strangeness of participatory experiments with shared agency documented elsewhere in the exhibition. The Omsk Social Club, a Berlin-based web3 collective, orchestrated an online roleplaying game called Heart of an Avatar <3 (2023), where participants shared a persona named Eastyn Agrippa, and worked together to compose a memoiristic philosophical tract on the relationships between avatars and their humans. The installation at HEK included several screens, arranged on a series of vertical shelves teeming with wiring, as if to better reflect the multiplicity of identities contributing to Eastyn’s story. Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst presented materials from Holly+ DAO, their project to authorize uses of an AI model trained on Herndon’s voice for music produced by the DAO. In a video from a concert venue, Herndon and Dryhurst’s collaborator Colin Self leads the audience in a singalong chorus to one of the pair’s compositions. A media player hanging beside the screen plays a track where the collective voice is recognizable from the video but the music it sings is quite different, with skips and warbles added in the process by the generative AI. The rest of the wall is hung with portraits of Herndon generated by Dall-E, from an NFT collection sold to create the Holly+ DAO treasury—a proliferation of an artist’s image supporting the project to do the same with her voice. Holly+ represents an experiment in using AI and web3 to create new kinds of relationships between artists and their publics.

Jonas Lund has been playing with a similar dynamic since 2018, when he first issued Jonas Lund Token to the collectors, curators, and critics who have an interest in his practice, allowing them to influence the decisions he makes in his art career. The installation at HEK included wall text detailing expectations of DAO members, a list of stakeholders in his work (organized like the names of patrons in a museum lobby), and charts showing how votes on various proposals went down. There was also a desk with a red phone which could be used to call the artist’s studio, and a computer monitor with scrolling text of transcripts of conversations between the artist and his callers about potential paths his career might take. In his book Surfing with Satoshi (2022), Domenico Quaranta comments that Lund’s quantification of and financialization of his network of contacts removes any human warmth from those relationships. The office environment of the installation underscores the business-like orientation of a project designed to highlight the artist’s position in the art world’s economic infrastructure, while also shifting that position into a new field. If the Omsk Social Club created a fictional story about this process through roleplay, Jonas Lund Token and Holly+ foreground the shape of the interaction.

In his 2008 essay “The Obligation to Self-Design,” Boris Groys argues that, for centuries of Christian civilization, people designed their souls for the eyes of God, but in the modern era the soul became externalized. People express the self through outward appearances, from fashion to online profiles. If the body is already the stuff of expression by the self, “Collective worldbuilding” suggests ways in which the artist’s soul and body can become the stuff of self-expression by others, by using web3 tools to collectivize the creative process. Teeming with screens and controllers, “Worldbuilding” is a novel museum experience, though the relationships it offers to audiences—dipping into enclosed, imaginary worlds, trying on readymade identities via avatars—will be familiar to most viewers, even while offering surprising, critical perspectives on them. In the end the form of the video game is about consumer choice, a way of experiencing various forms of agency. In an essay about the worldbuilding trend for Dirt, Terry Nguyen writes: “There is an excess of worlds to immerse ourselves in, but a dearth of meaningful connection to other humans.” “Collective Worldbuilding” offers a vision for a possible middle ground between the two—a positive vision of a grassroots, artist-driven metaverse that can support and sustain meaningful interpersonal connection. Together these exhibitions picture a crossroads in the twenty-first century media environment, with two possible directions of where things could be headed: a selection of readymade metaverses (and the potential for critical space to reflect on them) on the one hand, and collective self-determination on the other. What kind of world are we building?

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.