Avatar as Subject, Artist as Avatar

Two exhibitions that engage with the trendy notion of “worldbuilding” offer different visions of what the role of audiences in artist-conceived worlds can be.

It was 2007, the year the iPhone was introduced. In the Himalayan city of Darjeeling, Isaac Sullivan came across an image that would stay with him: a digital render of a white stucco house printed on to the side of a white building. “It showed this rendering … behind an uncanny green lawn which had these pixelated artifacts on it, all of which were interacting with the rough texture of the building beneath,” he later recalled. In the ensuing years—especially in the wake of the 2008 economic recession—Sullivan began to notice these kinds of images everywhere: cities were filled with unrealized construction projects, increasingly weathered renderings on the board fences around the abandoned sites. These strange pictures-within-pictures seemed to capture something about the way in which digital images, both online and off-, were beginning to overshadow and even constitute the material reality they were meant to represent.

Sullivan’s preoccupation with the complex entanglements of technology and the physical world is rooted in theories of ecology.

Since then, the US-born, Dubai-based artist has been preoccupied with the merging of the virtual and the real in the circulation of images. His project Hypothetical Spaces (2007–) features an archive of pictures taken in cities around the world and has yielded oil-on-canvas paintings, digital works that are generated in response to weather conditions, and a website. The archive includes a photograph of Niagara Falls encased behind Plexiglas next to a viewing platform overlooking the falls themselves, as well as a digital rendering of a chandelier on a construction wall outside the future luxury hotel in Palm Jumeirah, Dubai, that will contain it. Sullivan’s preoccupation with the complex entanglements of technology and the physical world is rooted in theories of ecology. His study of environmental interactions focuses not upon tidal estuaries or the dams of beavers, but rather on image transmission in the twenty-first century.

In 2020, Sullivan worked with a team of copyists in southern China to produce a selection of his Hypothetical Spaces images as oil-on-canvas paintings. Tashkent, for example, is a painting of his photograph of a car in the capital city of Uzbekistan, parked in front of a construction wall affixed with a rendering of a road seen from above. Although the paintings in this series draw on photographs taken in Reykjavik, Istanbul, Stockholm, and further afield, they also seem somehow of a piece with Sullivan’s current locale, successfully simulating the socio-economic reality of Dubai as an urban landscape that is filled with outsourced materials and spatial imaginaries created elsewhere.

In the recent episode of the New Models podcast on Dubai, Lil Internet characterizes the city as “the internet made material.” Sullivan’s HypotheticalSpaces.zone, produced in 2021, inverts this concept, enabling us to immerse ourselves in his pixelated renders through a labyrinthine microsite of infinite clicks. Each click generates new variations, different images of images floating on-screen, multiplying, and shifting in scale and clarity. The blurred backdrops of the site in some instances look like biological tissues viewed under a microscope, and in others like lots of tiny worlds seen through colored glass. The movement between the micro and the macro reflects the intricate entanglements between the web and the world, with the viewers’ clicks acting as simulations of movement and navigation as opposed to passive and static observations. A city that materializes images of other places while constantly visualizing itself is one that morphs infinitely. If a mise en abyme” is the infinity which opens up inside any operation when it is made to include itself, then HypotheticalSpaces.zone is an encapsulation of the internet that reflects its abyssal depth.

HypotheticalSpaces.zone is an encapsulation of the internet that reflects its abyssal depth.

The latest iteration of the project, created in 2022, also emerges from an intensified sense of the elsewhere within the present—and the tangible dimensions of data. A series of generative digital works, minted on the Solana blockchain, morph in response to the viewer’s location and the environmental conditions where the image originated. For example, Ruwais begins as a photograph of a rendering of a road printed on a construction wall in rural Abu Dhabi, set in a blue frame with a drop shadow. Over the next sixteen seconds, the image transforms according to the latest AccuWeather data: fragments of maps of rivers, drifting magnifications, pixel displacements, and thumbnail duplicates of the image appear according to the humidity, wind direction, and temperature in Ruwais and the current location of the viewer.

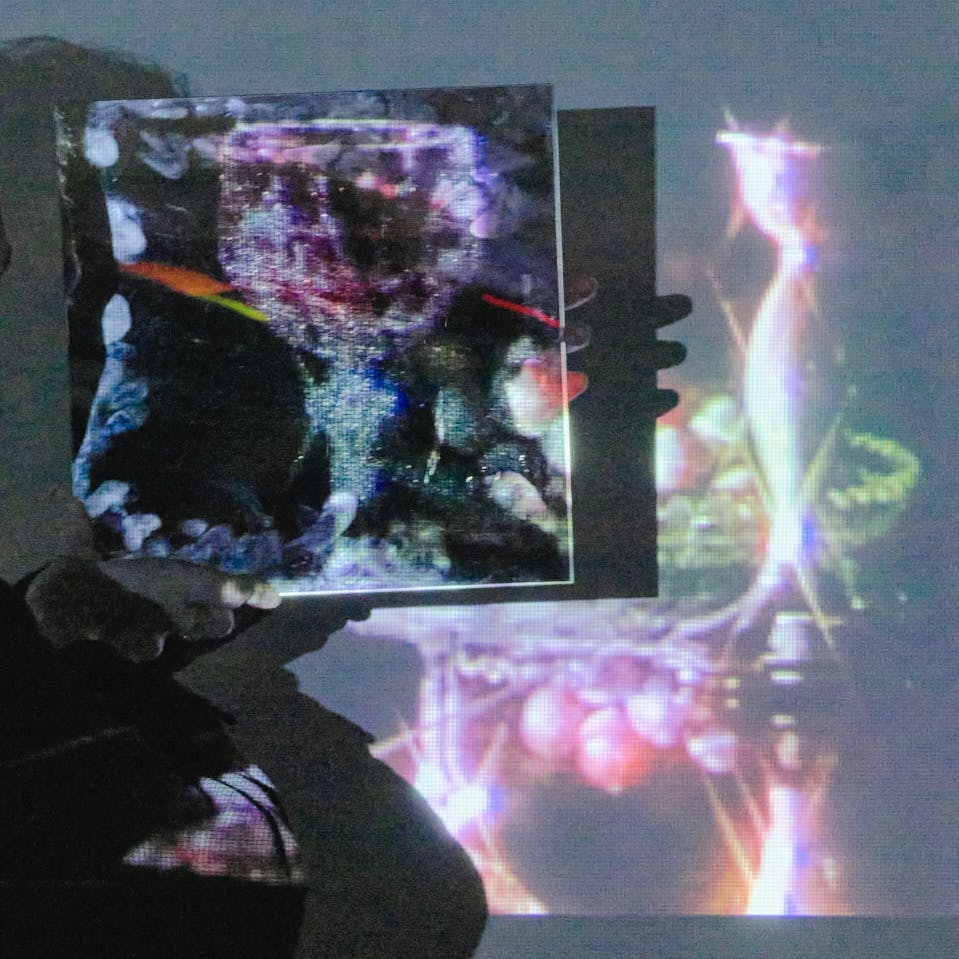

Cybernetic loops and iterative systems figure prominently in Utopics (2019–), Sullivan’s series of spatial interventions. He has introduced temporary modifications to a palazzo in Venice, a warehouse in Dubai, a church in Berlin, and a former ice factory in Mumbai using video and text projections, mirrors, sound recordings, and fire to highlight and magnify traces of the elsewhere in those particular locations. For instance, his photogrammetric scan of the palazzo’s chandelier made its way to the walls of Berlin’s neo-Romanesque St. Matthaus-Kirche, where it was flanked by a projection of candles flickering from the air displaced by subwoofers within a Dubai warehouse. In Mumbai, these images appeared alongside a live video feed in which viewers could watch themselves watching the images in real time.

If in Hypothetical Spaces, Sullivan casts images as what he calls “simple forms of non-human agency,” other recent projects engage more complex forms of the non-human. Chyron (2022) explores the emerging behaviors of artificial intelligence through an ongoing dialogue with an AI chatbot created in using OpenAI’s GPT-3 model “davinci.” The AI responds to his provocative questions on systemic thinking, the self, death, and the image through an avatar which is a digitally generated approximation of Sullivan’s face. The AI seems to talk and think like he does, which sounds like being stuck in the uncanniness of one’s own dream; the model is trained on the texts that Sullivan wrote for Utopics—gnomic fragments, exploring what Sullivan describes as “the preconscious topos of the human psyche.” Through the chatbot, the artist turns himself into a mise en abyme, allowing the AI to mirror, amplify, and glitch human thought.

The use of mise en abyme also features in Sullivan’s Echo Holdings lecture performances, which have taken place in galleries, repurposed spaces, and clubs in Singapore, Saint Petersburg, Amman, and elsewhere. In Echo Holdings x Machine Vision (2021), at Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai, the artist appeared live alongside footage of himself set in a video projection of the 1995 Japanese animated movie Ghost in the Shell—a film that similarly considers questions surrounding machine vision through the hybrid figure of the cyborg. Now, as new forms of artificial intelligence emerge—and accelerating environmental crises demand we not lose sight of our physical conditions—Sullivan’s ecological work with technological entanglements shows us that we are already inhabiting both the render and the real: that we can be everywhere all at once.

Dana Dawud is an artist, writer, and independent researcher based in Dubai.