Simon Denny & terra0

How do smart contracts enable nonhuman entities to govern themselves? Can the law accommodate the systems that blockchains make possible?

Glitch art resists historicization—it’s a set of processes and ethics in relation to technology that recur across technological eras. But if you did try to write an official history, you might cite Jamie Faye Fenton’s Digital TV Dinner (1978), which captures the glitches on the screen of a home video console game, as the starting point. Fenton worked with friends Raul Zaritsky and Dick Ainsworth on the sound and video editing and presented the piece at the third edition of Electronic Visualization Events, a series of live performances in Chicago which brought together artists and technologists. For Fenton, a computer programmer and games developer by trade—and self-described “gender-nerd bon vivant”—glitch art has always above all been a way to connect with a community of like-minded individuals. Over three decades later, when Ras Alhague was added to the Glitch Artists Collective Facebook group in 2014, the Polish artist had a similar realization: here was somewhere they, a queer trans person who had never felt they could live freely, could finally fit in. They immersed themselves in the community both online and offline, organizing exhibitions and festivals around the world. Alongside this, Alhague has developed their own “post-fetish photography,” in which glitch techniques are applied to their own erotic self-portraits. Outland brought Fenton and Alhague together to compare notes about their creative journeys and communities, as well as the political implications of glitch.

JAMIE FAYE FENTON In the 1970s I took a job with a company called Nutting Associates, which got the patent to build video games using frame buffers—the foundational technology that all our computers now use everywhere. I started off working on pinball machines and eventually started doing games as well. Then I moved with the company to Chicago, where I did a couple of obscure games.

I was looking to create a social network, and I wound up meeting people like Tom DeFanti and Dan Sandin—this cadre of computer artists, if you will. I frequently credit Tom DeFanti with having basically invented the idea of live coding. He did a couple of events called EVE—Electronic Visualization Events—which I participated in.

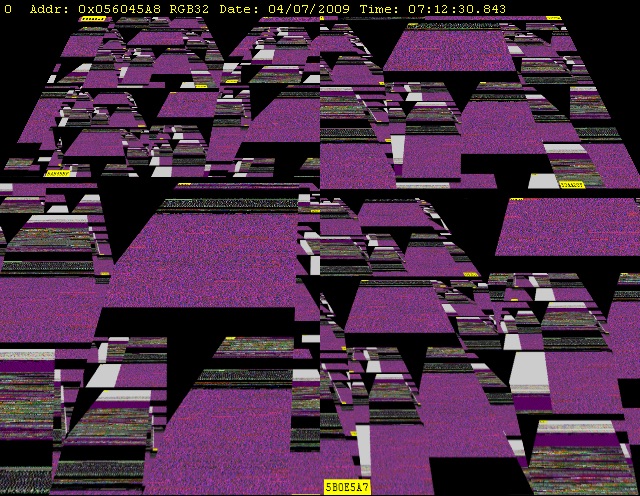

In terms of how I got into glitch, I noticed that when you power on a video game, if you don’t clear its memory you can see some interesting patterns. Or if the computer fails you also get interesting patterns. I was basically just seeing these things and thinking they looked pretty cool, and that I could make some art out of them.

I was in my early twenties. I had a little clue that I was trans but there weren’t lot of reference points in the culture to help me come out that way, so I was essentially a struggling kid trying to figure out how to have a love life and things like that. For me being an artist was sort of about fitting in with this whole other culture, as opposed to it being my primary calling. I think of myself as an inventor or tool-maker first, if you will.

RAS ALHAGUE My introduction to glitch art was in 2014—next year will be my ten-year glitch anniversary! I’m hoping to organize some kind of event, because it’s going to be the ten-year anniversary for a lot of people in my generation of glitch artists.

At the time I was studying at the painting department at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts in Poland. I’m not sure why I got in, because I never liked painting and I never wanted to paint. My main interest was digital art—mostly digital illustrations, comics, that kind of fun stuff. The academy was not a place for fun stuff. It was also apparent that there was a lot of sexism, elitism, which is especially weird when you’re in a supposedly progressive art space. I eventually dropped out.

It’s always been a struggle for me to connect with people offline, and I felt throughout my life that I didn’t quite fit in anywhere. One day a friend of mine messaged me and said: “I think I’ve found something I want to do for the rest of my life.” He introduced me to glitch art. I had seen some of it online but I didn’t know that it had a name, or that there was a massive history and philosophy behind it. He added me to the Facebook group Glitch Artists Collective. I always think of this as the moment where it all started for me. It turns out I, too, had found something I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I had found my people.

I think a lot of people are attracted to glitch art because it’s a community of misfits, of queer people, of trans people. I didn’t quite realize back then how much that applied to me too. Over the last ten years I’ve been through a lot of realizations, including that I’m also a trans person. It’s been a wild ride and being in the glitch community has definitely helped me to realize things about myself.

FENTON Yes, I’m always astonished by how many trans people there are in the glitch community. Recently I’ve been working with a music synthesizer called the Synthstrom Deluge. It’s a wonderful groove box with a matrix of buttons on it. It’s been available for about six years, and they decided to make it open source. Because I had written some software for it, they tapped me to help lead the open source project. Half the people on it are trans! I don’t know why. I’ve also been making very glitchy music on it.

ALHAGUE I was so young, maybe twenty or twenty-one, when I was first introduced to glitch. I didn’t really see it as more than an aesthetic. I see things differently now. I can see that there are some strong political and philosophical notions in glitch. A lot of people, especially in my circles, are very anti-capitalistic, very queer. Glitch taught me about what it means to be a glitch in a society.

Of course, glitch is also a beautiful tool, aesthetically speaking. The range of techniques is incredible, there are so many effects you can achieve. It was interesting to see how glitch became popularized in mainstream media around the early 2010s. There was a wave of music videos from popular artists, movie trailers suddenly using glitch art. Even Sephora had a commercial where the logo had an RGB shift.

But while this brings attention to glitch art, people who stay in the community stay for the people. I believe at its core glitch art and the glitch communities are about inclusion and accessibility and openness and open-mindedness.

FENTON I actually became aware of the glitch art community myself in about 2014, even though I’d been doing this sort of stuff on my own in various weird ways since 1978. It’s just that I was always doing other things too. But when I look back this concept does show up in my work. For example, when I was working on the VideoWorks software for MacroMind, I would wind up making art just to test it.

The origin story of Digital TV Dinner is that our whole gang would sometimes go up to a farm in Wisconsin, which was the perfect place to take hallucinogenic drugs. There was a particular drug that was called ALD-52, or Orange Sunshine. It was lots of fun: we would splash around in a creek, go for nature walks, all the good stuff you’re supposed to do when you’re tripping. One time, the trip was well under way and I was playing around on my Bally Astrocade—which I had actually helped develop the hardware and the software for—when I managed to come up with a glitch that kept rolling on and on and on.

I thought maybe I could get better art out of this thing than you could by writing Z80 Assembly code. So we took the Bally Astrocade and hooked it up to a circuit that we had developed that lets you do composite video output, so you could record it on a VHS or a three-quarter-inch deck. We captured a lot of glitches and tacked them together to approximate this vision I’d seen. A friend of mine, Dick Ainsworth—who’d had a lot of influence on how the Bally Astrocade’s audio system worked—did the audio. Raul Zaritsky did the video editing.

The work was shown at the EVE 3 event, and had a positive crowd reaction. I managed to misplace the mastertape at one point, so at some point I’d like to regenerate the tape from the best surviving copy and try to get something with less noise in it.

How we got from that to this wonderful movement in the 2010s is a long complex story. I certainly can’t say everybody saw Digital TV Dinner and said: “wow, look what Jamie did.” I was maybe a little bit ahead of my time. But it was definitely a lot of fun. And it has been heartening to see it turn into a phenomenon and get to meet a lot of neat people. It is true that this is a refuge for the neurodiverse, for kindred spirits.

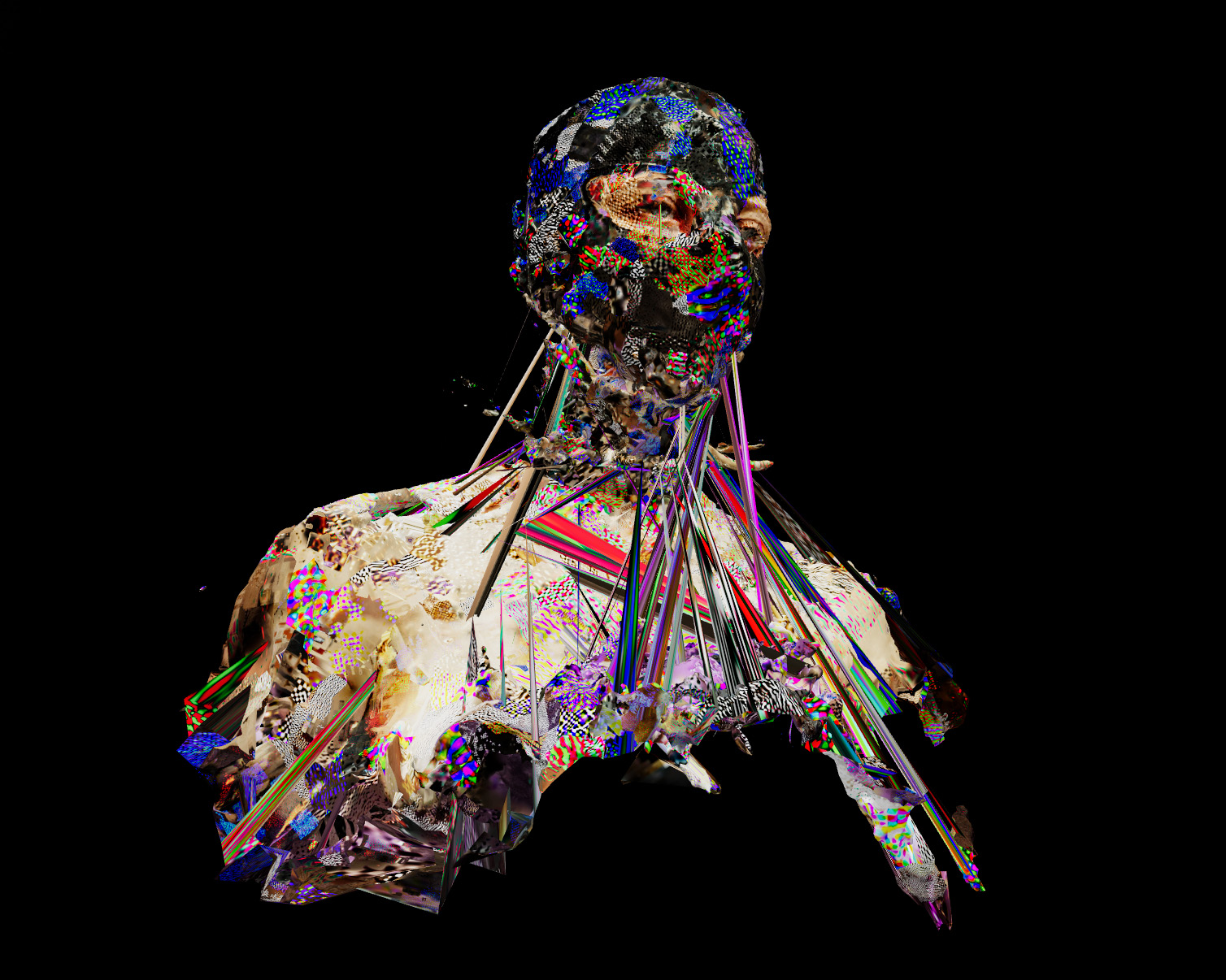

ALHAGUE For the past three years I’ve been working on my post-fetish photography and glitch art. The use of found images from the internet in glitch art had been bothering me. I think it’s fair if this is the way someone wants to express themselves, but even when I was able to use good stock images and mess with them, it never felt one hundred percent me. I couldn’t express what I wanted to.

In 2019, I went through a very difficult year. But one good thing that came out of that year was my relationship with Way Spurr-Chen, who I had met in in 2017 at the /’fu:bar/ event in Zagreb. He’s developed a few tools such as Moshy, for datamoshing. I use them all the time; if I ever have an issue, I can just ask my husband to help me!

Anyway, we got together, even though we were an ocean apart—him in the US, me in Poland. What we didn’t expect was the pandemic, which obviously restricted our ability to see each other. Because of this distance, we looked to other outlets to express our intimacy with each other. So I happened to have a lot of pictures of myself to work on.

FENTON Oh yes, I have some of those—from my party girl phase!

ALHAGUE Yes, and it was great to be in a relationship with someone who felt comfortable with me expressing myself and using my body in my work. It also helped me reevaluate my relationship with my body, to see it through a different lens, more as an art object, which was very liberating.

I call my work post-fetish because it relates to my experience of eroticism and kink. It’s also linked to the relationship between my art and the social media sites where I post it. I found the term “postfetish” through Instagram hashtags, after realizing that hashtags such as “fetish” or “kink” would prevent my artworks from being visible for anyone.

In my work, fetishism, queerness, transness, and glitch art are all very much intertwined. They all relate to the body and to my psyche. I was talking to someone recently about the relationship between glitch art and kink. Both the glitch art and the BDSM communities frown upon gatekeeping. If you have an interest, you’re encouraged to explore.

There’s also the way in which glitch is seen as something wrong—it’s an error, a mistake. It’s connected on some associative level with the state of wrongness. Kink and queerness, in the same way, are frowned upon, especially in certain environments such as the Catholic culture I grew up in.

FENTON There’s the concept of a “natural” glitch, a glitch you just find. One of the first natural glitches I ever saw was of frame store time-base correctors on network television. The video got really glitchy on this feed that went to the whole world: I knew why but most people didn’t. For me glitch starts with things that can go “wrong,” or are surprising, that can happen as a consequence of a technology that’s beyond the anticipation of its developer.

Only later did I realize that there’s a creative mode where you sit back and try things out and come up with something that you never expected, and that some of it will be good while most of it will be garbage. My Deluge synthesizer has about 480 songs saved on it and maybe twenty are good.

Dancing is probably what I do with the most passion and the least effort. It’s the glitchiest dance you could ever imagine! The reason I’ve never tried to develop as a dancer is that I’ve never managed to do it twice in the same way.

ALHAGUE I think it was Nick Briz who said glitch is not a mistake done by a machine. The machine is interpreting the data it is given correctly, it’s just that the result is something that we don’t expect.

FENTON Exactly. You’re not trying to make mistakes or things that don’t function, you’re still trying to make things that work out.

ALHAGUE For me that relates again to queerness and transness. We’re not in a state of wrongness. But we have maybe turned out not the way people expected.

As I’ve said, what has kept me in this community for so many years is the people. From the beginning I’ve been very involved in the community side of things, organizing meet-ups and exhibitions. Early on, I became an admin of Glitch Artists Collective. Then the first exhibition I worked on was “Glitch Art Is Dead” in 2015 in Krakow. That was a huge thing for us, and for its founder Aleksandra Pieńkosz, although at the time I definitely didn’t realize the impact it would have. Now we’ve had editions of the exhibition around the world. In 2018 I helped organize blue /x80, which was founded by Kaspar Ravel, and now I’minvolved in the /’fu:bar/ festival.

I’ve heard some people in the community describe events as an excuse to connect with like-minded individuals. For me these events are more than an excuse, they’re an extension of what we’re doing. They’re a way to get the best out of the community, and to present our work to people who are not connected to it. I’m excited to see more events happening in the future, so we can keep breaking shit together.

FENTON As long as we can keep coming up with stuff to break, we can keep breaking it!

—Moderated by Gabrielle Schwarz