Sam Hart

A curator and editor who has contributed to the discourse on art and the blockchain through projects in nontraditional spaces.

Over the past twenty years, Julia Stoschek’s art collection has grown into one of the most significant private collections for time-based media in the world. Included in this intentionally capacious category are works of moving image, photography, and sculpture as well as pieces that employ newer technologies such as VR and AI. But Stoschek never wanted to be just a collector. The Julia Stoschek Foundation also manages two public venues, in Düsseldorf and Berlin, where education and research take place alongside a program of events and exhibitions. The latest show, “Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age,” on view at JSF Düsseldorf through February 4, is an ambitious survey spanning more than three decades of artists who have drawn on video games—whether as an aesthetic influence or as an actual format—in their work. As a result of the show, a video game recently became the latest form of time-based media art to enter the collection. Anna-Alexandra Pfau, director of collections at JSF, spoke to Outland about the multi-faceted mission of the organization, and why “Worldbuilding” felt like an important exhibition to stage at this particular moment.

The Julia Stoschek Foundation is a nonprofit arts and culture organization dedicated to the public presentation, conservation, and scholarship of time-based media art. The foundation also manages the Julia Stoschek Collection, which features 930 works by around 300 artists. It currently runs two exhibition spaces: JSF Düsseldorf, which opened its doors to the public in 2007 in a former factory building, and JSF Berlin, which opened almost a decade later.

Today, our remit is very broad. It includes an exhibition program, performances, cinema screenings, workshops for students and children, artist talks and lectures, and a curatorial residency program, among other things. But it all began with the collection, which Julia Stoschek started building in 2002. As an overview of time-based media art from the 1950s and ’60s to the present day, it spans from early film and video works and installations by artists such as Carolee Schneemann and Bruce Nauman to computer-based works by a younger generation. The collection also includes photography and sculpture.

It’s very important for us to build sustainable relationships with artists, rather than collecting a hundred works by a hundred different artists. When it comes to acquisitions, we always look at the full oeuvre of an artist to select key works and then continue to follow the artists throughout their careers, growing with and reflecting their evolving practice. That is why the collection consists of several groups of works by one artist. For instance, we have sixteen works by Ed Atkins and eight works by Cyprien Gaillard in the collection.

During the pandemic we digitized all time-based works in the collection and launched the JSF Video Lounge. It’s a bit like Netflix: you can scroll or do a search using different tags. Around 250 works from the collection are now online—we plan to make all of them available over the next few years. With regular video works this is easy, but there are instances of computer-based works that are constantly evolving where we had to find a solution with the artist to instead present a section of the work. Ian Cheng’s BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2017–18) is a live simulation powered by artificial intelligence, so he suggested we present video documentation of the work instead.

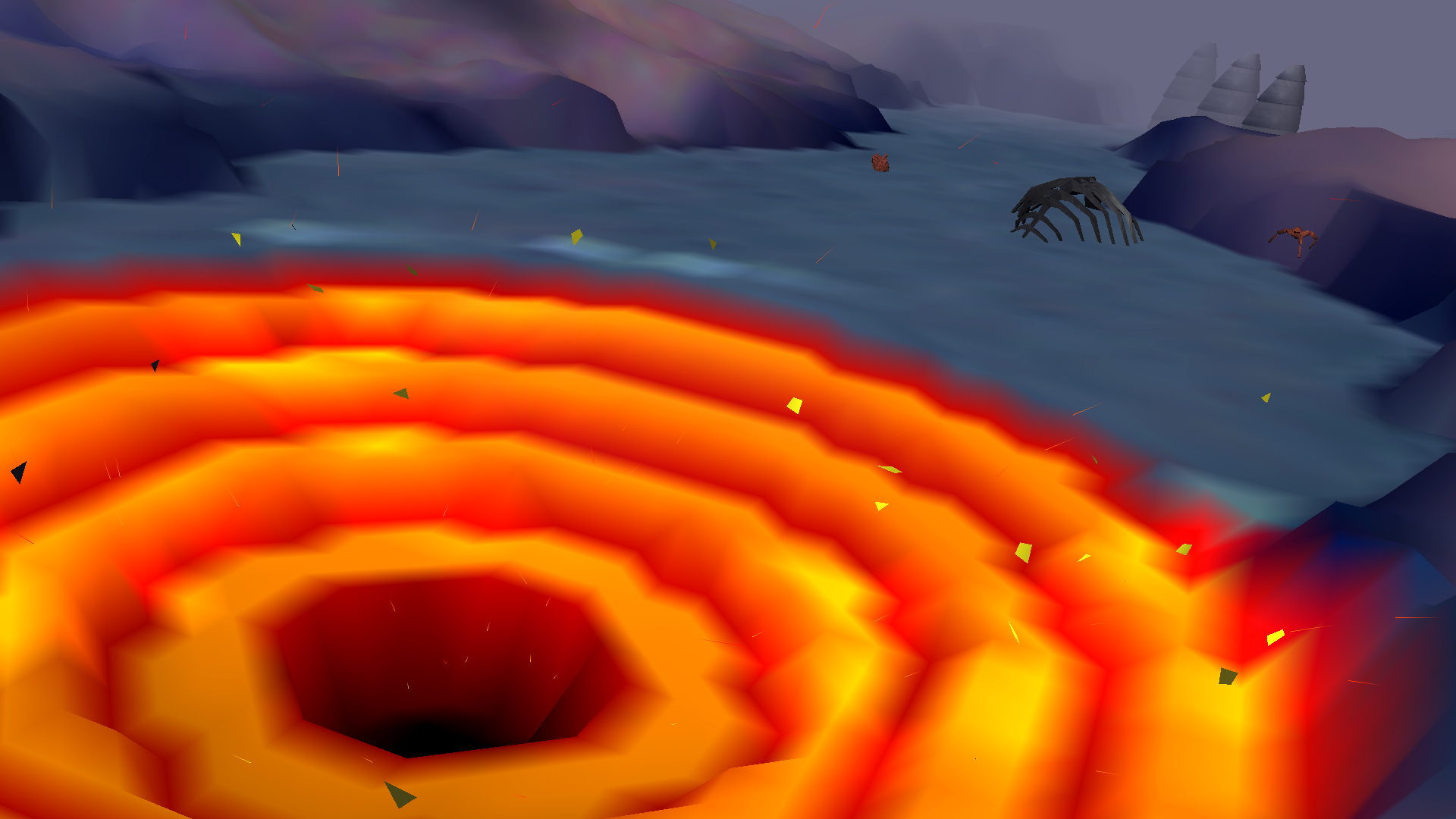

One of the most recently acquired works is Gabriel Massan’s Third World: The Bottom Dimension (2023), which is the first video game to enter the collection. The game, which explores the impact of extractivism on the land and peoples of Brazil, isn’t available in the Video Lounge, but you can download it for free on Steam. Third World is currently also part of “Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age,” an exhibition curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Initially the show was planned to simply be a “best of” from our collection, to mark the fifteenth anniversary of the opening of our Düsseldorf space. But Hans Ulrich wanted to do something completely new. The result is a survey of artists who have explored gaming in their work. We haven’t included any commercial games: the focus is on the relationship between gaming and time-based media art and how artists made gaming into an art form.

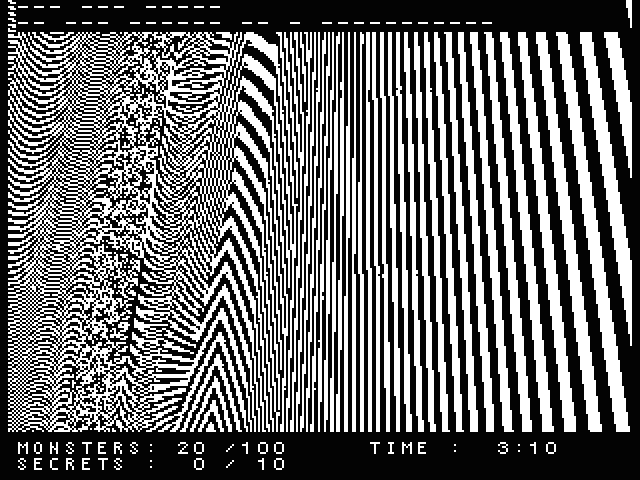

There are three generations of artists in the exhibition. Rebecca Allen’s The Bush Soul #3 (1993) is an early example of an AI system as artwork, and JODI’s Untitled Game (1998–2001) was made by modifying the graphics and software code of an existing computer game. The second generation is represented by the so-called “digital natives” who employ the aesthetics and technologies of games—Jakob Kudsk Steensen, for instance, who uses game engines to create his VR environments. And then there are artists born in the 1990s who are producing their own video games as works of art, such as Gabriel Massan and Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley. Over the course of the exhibition, additional works have been added to the display—the idea was for it to evolve in versions like a video game.

An exhibition featuring this many computer-based interactive works requires certain adaptations. For example, we have lots of visitor service staff in the exhibition to assist visitors with the equipment. We have produced special game instructions for every game-based work. There’s also a technical supervisor on call, because if a computer is running for eight hours then you can expect issues with the software. Last year a version of the exhibition was also staged at the Centre Pompidou-Metz. We plan to organize further iterations with other venue partners through 2026.

Billions of people play video games every year—in the introduction to the exhibition, Hans Ulrich Obrist writes that this form of entertainment is “to the twenty-first century what movies were to the twentieth century and novels to the nineteenth century.” It’s no surprise, then, that artists have become increasingly occupied with this new medium. I doubt they will stop any time soon.

—As told to Gabrielle Schwarz