Exclusivity for Everyone

Jonathan Monaghan connects aspirational consumption of the past and present in a site-specific installation of digital art.

On December 1, 2020, Ethereum shipped its “beacon chain,” a new protocol for consensus and coordination across the network. It heralded the replacement of a proof of work protocol—which requires computers on the network must solve complex math problems in order to verify transactions—with proof of stake, in which computers become eligible to validate transactions by putting a certain amount of cryptocurrency in reserve. Since then, the final transition has repeatedly been deferred several months into the future. Adopting a proof of stake consensus protocol presents an assortment of scalability and security challenges, but it will substantially reduce the energy consumption of Ethereum and therefore has come to stand for a sustainability effort. In the meantime, millions of computers around the world, most of which are not using renewable energy, churn around the clock to process about fifteen transactions per second. As Ethereum delays the transition, the carbon cost of the blockchain continues to escalate.

Kyle McDonald addresses those costs in Amends, a project that launched May 16. He released three NFTs for sale on OpenSea, Rarible, and Foundation, at a price equivalent to the cost of offsetting the carbon emissions incurred by each marketplace. Amends is a sobering reminder that even improvements to the energy efficiency of blockchain technology will not repair the cumulative damage. “The science shows that even if we end all emissions today, we still need to remove hundreds of billions of tons of historical greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and ocean,” McDonald said in a statement.

The more energy these platforms spend, the more money they make.

The works for sale, produced in collaboration with the artist and designer Robert Hodgin, are eight-second videos. At the center of each is a digital sculpture: a glass block filled with a material connected to an environmental organization that will benefit from the sales. They spin rapidly, evoking the dizzying NFT market moment of mid-2021 (McDonald has also fabricated physical versions of these sculptures, which a collector can obtain by purchasing and burning the associated NFT.) Amends for Foundation is filled with shredded refrigerant cylinders; it represents the work of Tradewater, which locates and safely destroys the parts of discarded appliances that hold chlorofluorocarbons, hydrochlorofluorocarbons, and other gases that do far more damage to the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. Tradewater has found 5 million canisters but estimates there are 9 billion more around the world.Amends for OpenSea holds olivine, a naturally occurring green sand that Project Vesta introduces to the ocean in order to both capture carbon dioxide and remineralize acidified waters. The glass block in Amends for Rarible brims with carbon-rich soil, representing the work Nori does to remove carbon dioxide from the air and bury it in the ground. While each NFT is conceptually linked to one organization, the revenue from each sale will be split evenly across all three.

The smart contracts for these NFTs regularly update their prices to reflect the tons of carbon dioxide emitted by the marketplaces, and will continue to do so until Ethereum implements proof of stake. The pricing also takes into account the emissions related to the works’ own presence on the NFT marketplace, as well as the marketplace and exchange fees. Additionally, the price includes the overhead that will be incurred when Gray Area—the San Francisco-based art-and-tech nonprofit that is facilitating the donations—transfers ETH into USD to pay out the three offset partners. The numbers are clearly presented in a financial breakdown available on the project’s website. OpenSea’s 2.5 percent commission means they will receive more than half a million dollars simply for hosting the sale of this NFT, and this will increase every minute in tandem with their carbon emissions. The more energy these platforms spend, the more money they make. The breakdown clearly shows the cumulative nature of the damage, as well as the benefits that companies reap from doing harm.

Amends is the culmination of a year of research and development. In April 2021, McDonald began working on a directory of total gas and transaction fees on major NFT marketplaces in response to a challenge issued on Twitter by investor Nic Carter. McDonald shared a Google spreadsheet documenting his findings and produced a dashboard translating the data into graphs for those who didn’t want to sort through the data themselves. It has been running ever since, and is the basis of the pricing for Amends.

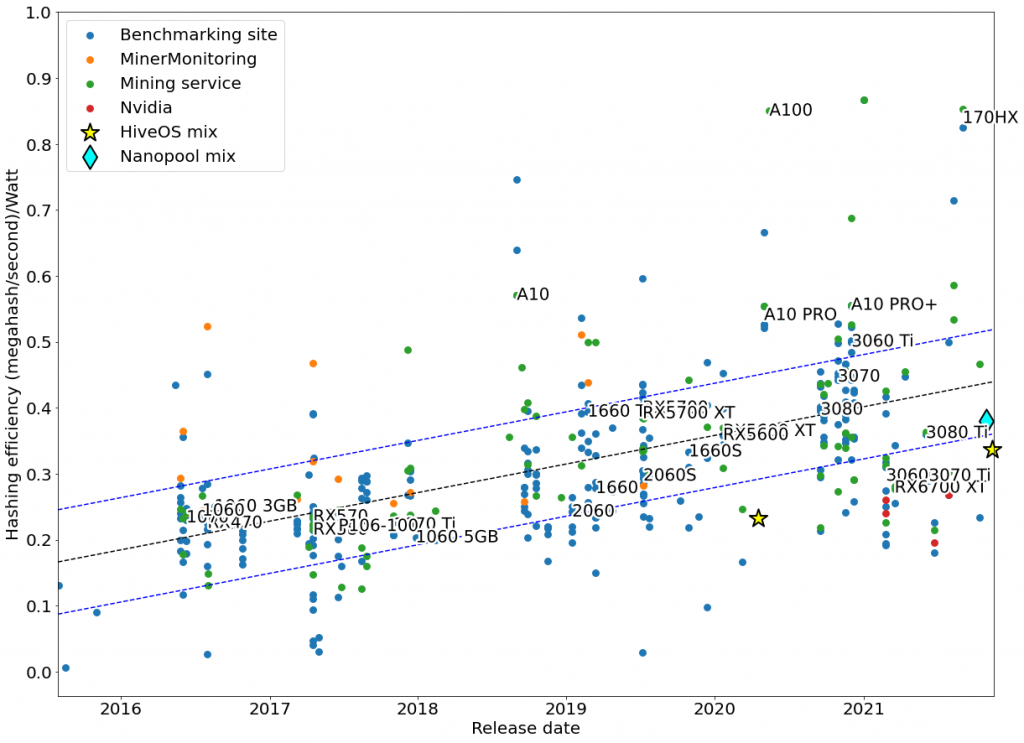

Previous efforts to calculate carbon emissions of NFTs have excessively inflated or minimized their impact. McDonald’s analysis aims to provide more carefully substantiated information so that people can make more considered decisions about where to put their money and their work. The project extracts data to calculate viable emissions numbers, revealing important facts in the process. Art constitutes a small portion of activity on the Ethereum mainnet. CryptoKitties collectibles produced the most daily fees and transactions until January 2021, when they were overtaken by the gaming platform Axie Infinity. And even collectibles and gaming are marginal compared to the extensive trading occurring in the defi space. McDonald’s research demonstrates that criticism about the energy costs of the blockchain should be directed not at artists but at the crypto traders who wield significantly greater transactional influence.

Nevertheless, amid a climate crisis, we are all culpable for our energy costs. Small choices matter. The fact that corporations are responsible for over 75 percent of energy consumption in the United States reminds us that chastising individuals for their microwave and air conditioner use cannot be the extent of our efforts to curb emissions. But it does not obviate our individual responsibility, either. And artists have a special role to play, since art’s visibility and cultural power gives them an opportunity to pressure organizations to adopt better practices.

McDonald’s work as an artist frequently entails such interventions. He was a member of the Free Art and Technology Lab (F.A.T. Lab), a collective that advocated for open-source technology and free information in the face of encroaching corporate control over the internet. His project People Staring at Computers (2011) involved installing software on computers at Apple stores and then publishing photos of the customers who used them, to raise awareness about the pervasiveness of surveillance in consumer computing. Apple filed a complaint and the Secret Service raided McDonald’s apartment—a foundational experience that affirmed how law enforcement and regulatory systems serve the powerful and not the public, but did not curtail his interest in using widespread technologies to demonstrate their dangers. Facework (2020) is a game that asks players to imagine themselves as gig economy workers, and uses facial recognition technology to pair them with potential jobs. It reveals how machines misinterpret as they exploit. With Amends, too, McDonald points to a technology’s harm and makes the motives and implications of his use of it as transparent as possible. The project has required overcoming significant legal hurdles, so McDonald publishes all the agreements he had to prepare so that audiences can see the challenges of pushing back against big platforms.

By participating in NFT marketplaces to enact his critique, McDonald recognizes his own culpability, rather than taking a moral high ground to blame and shame.

Some may think that as long as they don’t use blockchain, they are not involved in the damage, but this is to misunderstand the world in which we live. We are all culpable. Some of us more than others, certainly, but blockchain is just an extension of our dependency on mobile technology and the global economic situation. Even if you’ve never used Photoshop, you are still part of a society that adopted face and body filters that reproduce sexism and racism. All our computers depend on cobalt mining practices that expose African workers to harmful chemicals and dangerous labor conditions. By participating in NFT marketplaces to enact his critique, McDonald recognizes his own culpability, rather than taking a moral high ground to blame and shame.

McDonald’s efforts to reveal the economics underlying the playful NFT landscape betray the current exploitative market practices that replicate Web 2.0 and undermine the aspirations of those who believe web3 can be a more equitable environment. These platforms are the organizations that can choose to make change, though most currently shrink from that responsibility. They are complicit in the devastation, as we are only culpable. I hope that three among the many tech billionaires not only buy these works but also commit to sustainability efforts alongside their peers. This is McDonald’s hope, too. Amends forcefully argues that sustainability efforts can no longer just plan for a better future. They must respond actively and creatively to the damages wrought to date.

Charlotte Kent is an assistant professor of visual culture at Montclair State University and an editor-at-large at the Brooklyn Rail.