Ira Greenberg & Ivona Tau

Two artists discuss how their use of AI models has changed their approach to painting, drawing, and photography.

What is the relationship between art and its mediums? How does the artist’s technique communicate values to the public? What are the connections between fine art and traditional or mass-produced modes of production, like ceramics and photography? These issues are raised in the following conversation between Fang Lijun and Lei Lei, two Chinese artists of different generations who are experimenting with a new way of making art with their digital commissions for Outland’s Marketplace. Fang is well known as a pioneer of cynical realism, a movement of ironic and humorous art that responded to increased political pressure following the Tiananmen Square protests. Lei draws much of his source material from that same period. His videos incorporate vernacular photography of 1980s and ’90s to build historical narratives from collective memory. Fang and Lei discussed the role of technology in their work and how to address the audience in ways that transcend time and geographical limitations.

LEI LEI When an artist works with video or moving images as their primary medium, there’s a danger of getting addicted to technology. I care more about feelings, and what can be communicated to the audience via the moving image. Nowadays, with the development and convenience of technology, everyone can shoot and obtain video—so what’s the value of video art? Readymades, found footage, old photos, and animations are all weaved together in my practice. It’s a relatively democratic way to convey the message. It hands the power of understanding these images to the public.

FANG LIJUN First, let me draw an analogy to the figure sketch. When you draw the figure, the most precious thing—apart from the composition and the characteristics of the human body—is the atmosphere. The temperature, smell, and the movement of air that you feel in front of the subject matter just as much as the person’s appearance. Artists need to take the same approach to working with high-tech tools.

Second, in the early 1990s Chinese artists started getting more and more exhibition opportunities, but I saw too many painters just showing off their skill in their paintings. How do you know artwork is good? When the audience has left the site of artwork, and they recall something that they didn’t think or see clearly—that is good art, because a psychological relationship has been created between the work and the individual. This belief has had an impact on my later work: I always try to avoid showing off technically as much as possible and I don’t consider it a way to connect with the audience.

My third experience has to do with the use of mobile phones. When I bought a mobile phone in China in 1993, most Chinese couldn’t afford them. The vast majority of Chinese artists considered owning one corrupt or bourgeois because they didn’t believe that art should be involved with trendy and advanced technologies. But today, thirty years later, it is impossible to live without a smartphone. Art once served religions, nobles, collectors, and institutions, but this relationship has changed, and the power of art is no longer monopolized. I think artists should encourage social openness and pluralism so that everyone can find and enjoy art.

Last but not least, what is virtuality? It doesn’t mean that things don’t exist just because we can’t see or grasp them. Art should be more open. The museum is not the only place where you can perceive it; virtual spaces can achieve the same effect. Artists need to take advantage of technical possibilities to work toward satisfying social needs.

LEI I want to just follow this and talk about my feelings regarding the value of working as an artist. When the old documentaries and photos are projected on the screen in a black box, the audience sees the same images, but they bring their own understanding. The viewer’s perception is based on different identities, cultures, and educational backgrounds, then the images generate new concepts and meanings. It is not given by the artist but created in this space. Like you just said, the power of art should be handed over to the audience. The artist is not a dictator who tells the audience how good the technique is, or what the story is. I don’t use archives for the sake of nostalgia. I hope to communicate with the audience through them, by making these images open to the public.

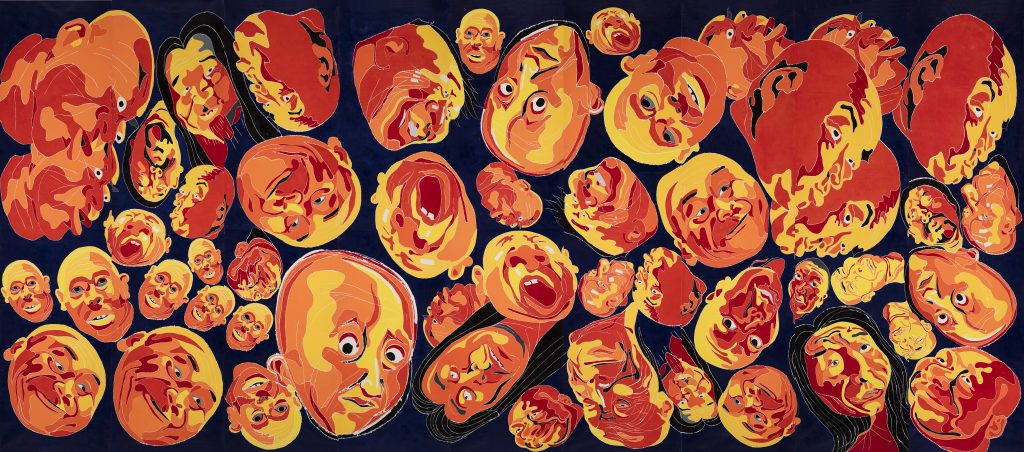

FANG Most people know my artwork from the paintings of the bald-headed character I made in the late 1980s. I moved to the Yuanmingyuan Artist Village in July 1989 when I graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts. The model in the picture is a young teacher from the law department of Peking University. We were constantly hanging out together at that time, having meals and drinking at his place. He was a very naughty guy, and the painting was derived from a photo we took.

The artwork was created in a very organic state, but to be honest it took a lot of effort to paint. In the Chinese art industry at that time, artists couldn’t just reduce the image of a figure to something so simple. I wanted to polish the details into a picture that forces us to face the subject directly. It’s not representative of the visual language we learned at the university, nor does it resemble the general painterly language found in art history. It was an almost instinctive act. I have always said we expect to pursue the whole picture of the world from the outside, but it is better to look inside for the truth. The direction of the universe is not from the outside world inward, but from the inside of the human body outward. The instinctive reaction at that time and the rational cognition come down in one continuous line.

LEI Is there truly a new thing that can be created by artists today? With the explosion of all kinds of images on the internet, what is the value of a new image nowadays? That’s the reason that I use many archives in my work. It doesn’t exactly solve this problem, but the shadow of images projected on a screen provides space for the audience to imagine and reflect. In this way, I reduce the threshold of technology to the bare minimum, so the power of art is handed over to the public.

For example, when my work Breathless Animals (2019) was screened at the Berlin Film Festival, many East German audiences said that they had photos like the Chinese ones in the film. They could see the similarity between each culture’s collective memory of socialist architecture and modernization. The response was also the same when it was screened in South Korea. These images are sourced from older archives, but they have a universal quality that can radiate new value across countries and contexts.

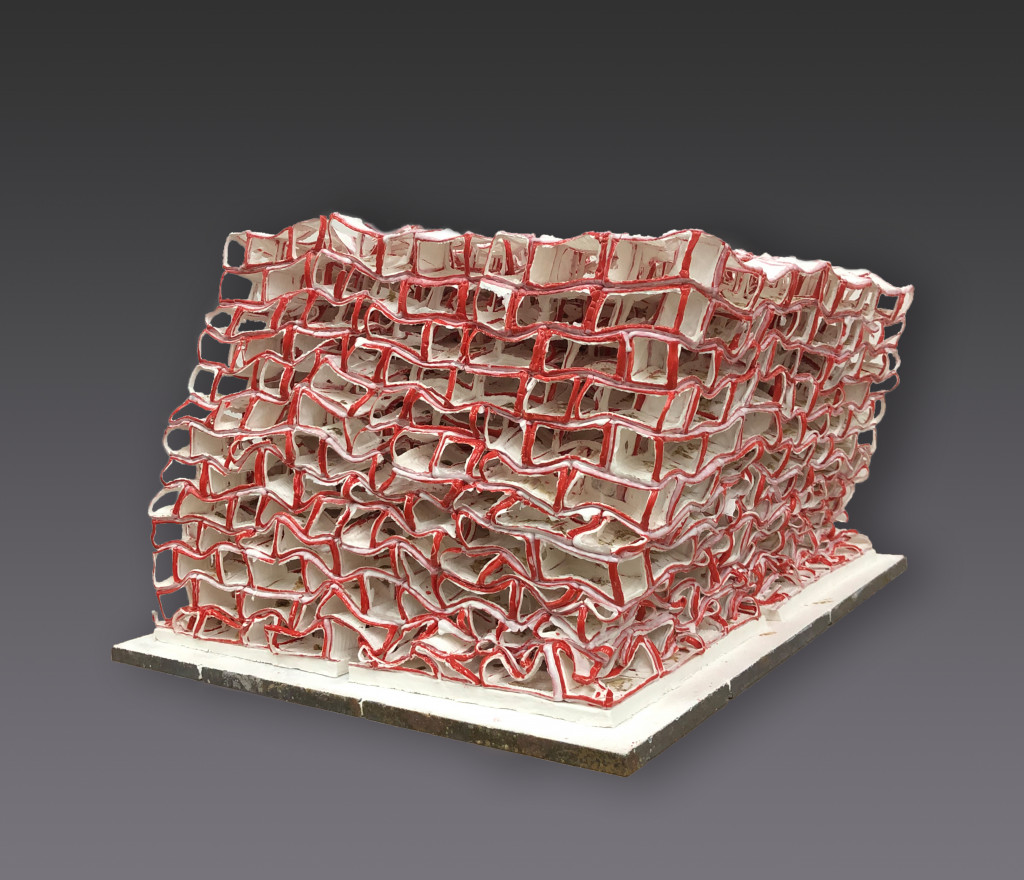

FANG Regarding the artistic format and language, I work in traditional Chinese ink painting, oil painting, printmaking, and ceramics. When we look back at the development of printmaking and ceramics, it’s important to understand the materiality and the process, because both mediums result from an effort to pursue standardization, large-scale production, and industrialization. Meanwhile, fine art is about the pursuit of originality and rarity. Now, we have fallen into a paradox where artists pursue creativity in a standardized way. Printmaking and ceramics enable me to achieve a state of freedom and liberation. The materiality of objects and tools need to be liberated, just as humanity does.

I don’t like to be limited by my mediums. I approach artmaking with the subject and raw material, and then find the topic or question that is suitable for solving. In the 1990s someone asked me how I could make oil paintings that look like posters. I was just trying to go around our industry’s rules and get straight to the point. That’s how I worked at the time.

Most of my ceramic works have been nonfigurative since 2012. I attempt to present the threshold between destruction and existence through the flaws and fragility of ceramics.

Another main part of my work in recent years has been creating teaching materials on the theory and practice of painting. I hope individuals who have never learned to draw can grasp the essentials of drawing or painting quickly from these textbooks. I think I have found the basic unit of painting, and I want to share it with those who need it. I hope it can yield results that go outside the rules followed in our art industry and avoid the misunderstandings that happen in training.

This is very significant and meaningful to me personally. We must maximize our experience in our short lives. I want to share with more individuals in this society. I learned to draw in an amateur art class, and I have been trained by many teachers. In the process, many mistakes were made that can be avoided completely. I don’t want people, around me or far away, to suffer this kind of pain and waste their lives. It’s a disaster. Art and education should be free and accessible to the public, and they definitely should not restrict people’s ideas.

LEI Your words really touch me. There’s a similar problem with the logic of the film and moving image. We need to resist the current hegemony. We have to face the consumerization of images. When moving images serve to convey just one opinion, the result can be crude. I believe that artistic language should be diverse, ambiguous, and vague, especially in the present.

You also mentioned the issue of art education. I teach at CalArts. The problems in artistic language or education are a global problem, especially under the restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic. I don’t tell students what is right to say. Sometimes we come to answers and judgments simply, but more ambiguous answers can respond to what is happening in the world.

FANG During our conversation, an image kept flashing through my mind, and I want to share it with you. It might explain my attitude as an artist.

I once drove to Xinjiang with my friends. We saw a scene of sheep trading in a canyon near Ili, where the Kazakhs live. There were hundreds of sheep and no grass, just sand. Sheep moved and dust rose. Herdsmen and traders kept surrounding and driving the sheep into separate decks of the trucks. I saw a sheep take a few steps when the herdsmen whipped them forward; then it slipped off without noticing. There were many sheep who wanted to run away, but they succumbed in the end. When all the sheep had been put on the cart, only this one got away. The herdsmen and traders left without noticing the sheep. Although it was not in a hurry, it had never forgotten the will to escape. I was touched at that moment.

Despite the disparity in power, it still was able to find a chance to survive. Perhaps we can see something similar in the intimate but delicate relationship between the individual and society.

—Moderated and translated from Chinese by Leo Li Chen