Sofia Crespo & Fabiola Larios

The artists discuss their work made with generative AI—and what the technology can teach us about the human mind.

If institutional critique examines the conventions of displaying art, from cultural biases in museum collections to the architecture of galleries, then infrastructural critique looks at how institutions function in broader social and material networks. Artist projects that use blockchain technologies not to produce digital assets but to build alternative behaviors within and around institutions can often be categorized as infrastructural critique. One such initiative is Dayra, a cryptocurrency being developed to facilitate the act of sharing by a Palestinian collective called The Question of Funding, recently featured at Documenta 15. Dayra posits another framework for understanding the resources required to run a cultural space, providing a way to involve people, talents, and services without exchanging money. Another example is Fractional Assembly, a yet-unrealized proposal by artist and writer Maryam Monalisa Gharavi to harness a museum’s wasted electricity to mine Bitcoin. The concept grew out of her studies of energy economies as the “one-woman collective” Oil Research Group (ORG). Gharavi spoke with two members of The Question of Funding, artist Yazan Khalili and programmer Abed, about extractive economies, frictionless capitalism, the social dynamics of Web 2.0, and the value of unfinished projects as engines for thought and collaboration.

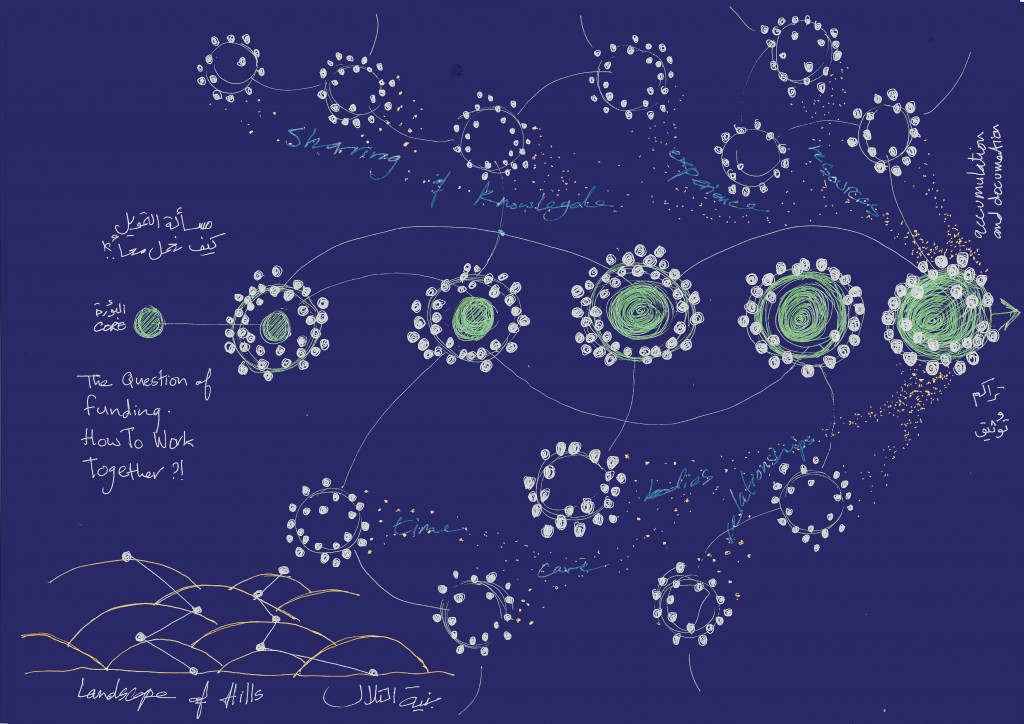

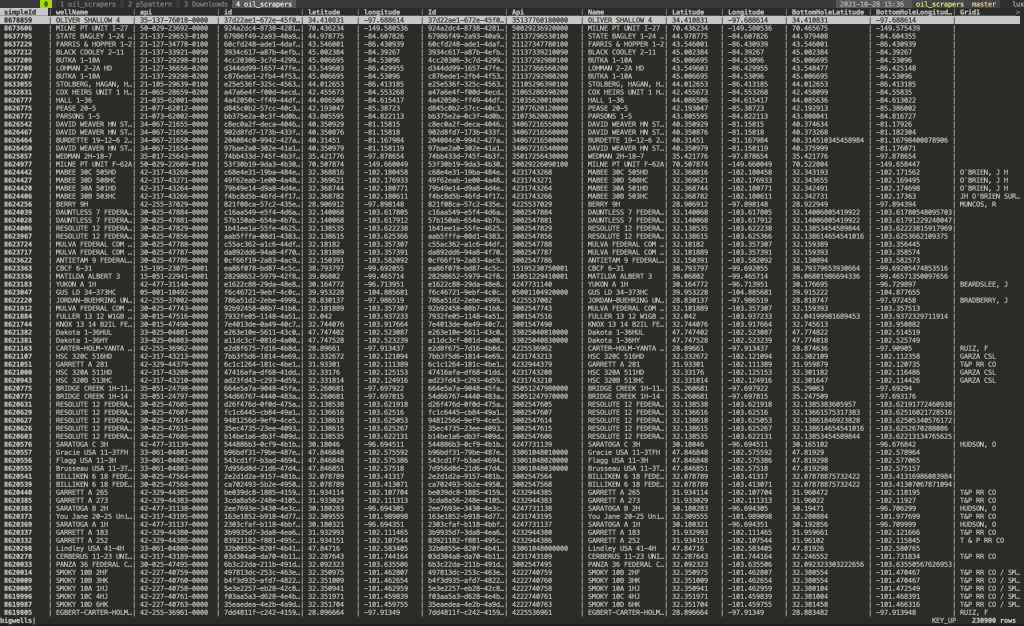

YAZAN KHALILI Dayra is being developed. We have not yet tested it on the level of use. We’re testing it now on the level of concept. It’s been out there, at Documenta and elsewhere, and people are engaging with it conceptually. Abed is building up the blockchain architecture. We’re working on the design and the user experience. It’s not just a whitepaper, to use the language of the blockchain.

ABED We started by selecting the DLT [distributed ledger technology] we see fit for us to use, working by a process of elimination. We decided how we wanted to onboard people to the network, and excluded all the DLTs that don’t suit our cause and use cases. We started with the UX—onboarding, account recovery, building your Dayra, building trust. We’re working the modules independently, and putting them together like a jigsaw. At the moment, our base smart contract is online and we can interact with it. The web app is in the internal test phase. Hopefully by the end of October, we will have a small group testing it.

KHALILI We are working in our ecosystem in Palestine. While we’re developing the technology, we are also working on the ground to better understand how to use it in the community. Initially, we wanted to work with compost. We called the project Zubalacoin—zubala means trash. The idea was that people could bring their organic waste, which can then be used to make fertilizer,and the people would earn units based on how many kilograms of waste they contributed. Then they could use the units to buy produce from organic farmers. We worked a lot with farmers and households, but discovered too many gaps. It didn’t open up to different economies. We needed to intersect with more kinds of production. So after working on our first model we realized we needed to expand it and make it less dependent on one kind of minting process.

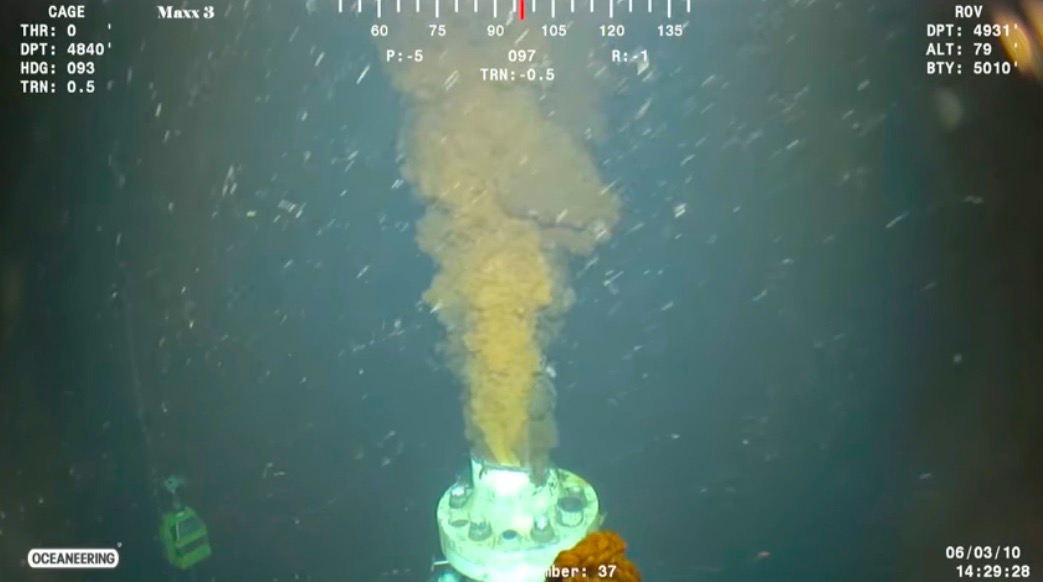

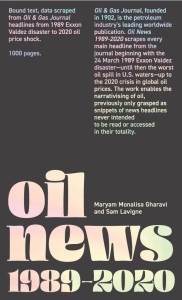

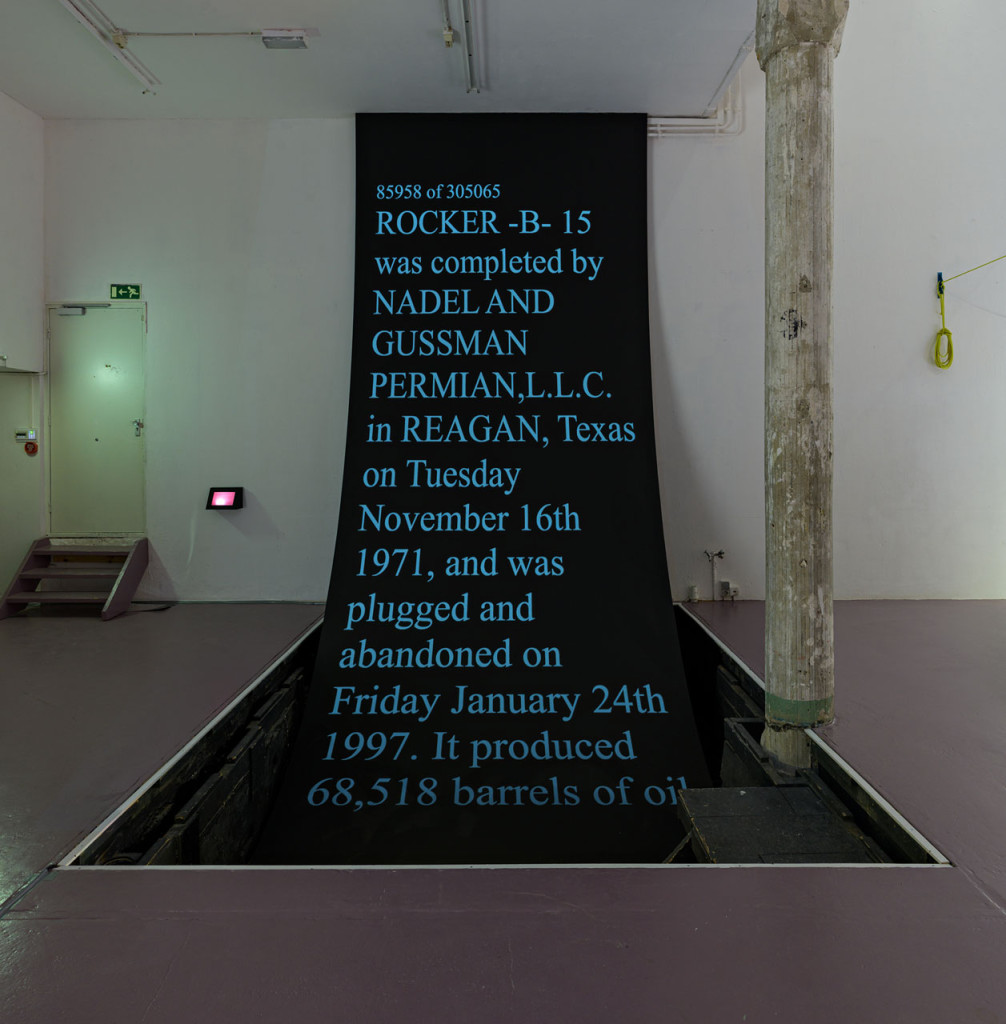

MARYAM MONALISA GHARAVI I see what you are doing as infrastructuralcritique instead of institutional critique. That has some bearing on how I conceived of a turnkey Bitcoin operation. In 2021 I created a proposal called Fractional Assembly. The mission was to siphon excess energy produced during periods of dormancy in an art museum into Bitcoin mining. The wasted energy from the building when it’s not in use would be pipelined through an ASIC miner to produce Bitcoin. One of the mottos of the project was “energy is precious, data is precious.” I wanted to work with Bitcoinbecause it is arguably the most immutable currency. You can’t create more of it, you can only mine it.

Bitcoin is, of course, incredibly energy consumptive. I interviewed Bitcoin miners around the world, particularly in the United States. They said that although non-miners tend to understand proof of work as incredibly wasteful, it is necessary. It’s 90 percent wasted energy, but the miners said that 85 percent of this energy is renewables, and often it comes from a surplus. Sweden, for example, has an abundance of hydropower. When used, that power goes back into the ground. So miners use a lot of power that would otherwise be wasted. But these discussions made me wonder: What would it be like to conduct a currency transfer from waste power and build a turnkey mining operation at an art institution? How many times have we passed by an art or academic institution that keeps the lights on 24/7? What happens to this wasted energy? What if someone captures it? Fractional Assembly could only transpire in collaboration with an institution. I couldn’t do it in my own home.

For this work I was looking at what I would call an art and infrastructure lineage. In the mid-1960s, a group called Experiments in Art and Technology brought together a large number of engineers and a smaller number of artists to work on performances that incorporated new technologies, and to place artists within technological industries through cooperation and industrial sponsorships. They ran the Technical Services Program where artists conceptualized highly technical works and collaborated with engineers and scientists to realize them. Artists at the time were asking: how do you move the value of art away from highly contingent short-term indices toward longer-lasting outcomes? As an artist you can take 50 percent of a gallery sale, and then have nothing to do with what happens to that work once it leaves your hands. What would happen if we as artists and collaborating institutions were to think about financial outcomes over a longer period of time? The research I was doing on oil, gas, and currency asset classes helped me put together Fractional Assembly as a concept. But the proposal was rejected. Twice.

KHALILI Your project is very interesting in relation to what we’re trying to do with institutions: How do we expand them beyond their claim on what they think they know? We are looking not so much at institutions as much we are at the infrastructure that makes them possible. Working on Dayra comes from a critique of economy.

Institutions depend on funding, philanthropy in the US, state funding in Europe, and donor economy in Palestine and the region. You need to adjust your proposal and reporting for the sake of the donor. You need to form the institution in a certain way in order to get funding. We can’t imagine art and culture without institutions. It’s not just a matter of budgets—the way we exhibit our work has shifted to fit institutions, to accommodate their limits and their restrictions.

What are the resources that allow cultural production to happen? Funding already exists in the community. If we can create economic structures that recognize it, we can begin building and acting upon different types of resources. Cultural institutions do not only need money to function. They also need knowledge, time, interest, spaces. Right now many cultural institutions cannot access those resources without financial resources. They can only be measured, exchanged, and stored with money.

When the lockdown began, cultural institutions were coming together and demanding more money to be able to survive. At the same time there were all these people who had no jobs. Ramallah is very much based on service economies. People who work in cafeterias and coffee shops and bars were suddenly without jobs. As cultural institutions were meeting to ask for more funding, service workers put up posters saying that they needed support. But the two could not speak to each other.

This made us realize that we need to think of the interdependency of art and culture and other economies. We had to rethink this kind of relation between artists and freelancers, small businesses like farms and design studios, and the household economy. We began to create an infrastructure that allows these economies to come together and depend on each other. So yes, it’s not only an institutional critique but also an infrastructural critique.

GHARAVI Discourses on Israel and Palestine avoid the financialization of contemporary colonialism at their own peril, because we see what daily life in Palestine looks like. When I was in Palestine going from Jerusalem to Gaza, in a taxi that had its own special tag for the occasion, Palestinians would point out sites that Israel bombed and the US rebuilt. The unsaid statement was that the funding to rebuild could only exist because of the destruction. In other words, there’s an ecosystem of destruction and re-creation that is an essentially sustainable model, but of course a monstrous one.

It was so banal and so invisibly violent because it forces this dependency forever. In the infamous “Ramallah bubble,” the illusion of an open market amid an impoverished occupied state, people are left to fend for themselves in very piecemeal terms. As you describe, cultural spaces are having the same problem. It’s the outcome of an architecture that is incredibly unjust. The disconnection people feel on an emotional, familial, and communal level is not because of a lack of creativity, or wealth, or agency. It is the outcome of a model in which Palestine is extracted from as a dependent space.

KHALILI What other kinds of economic structures are you thinking about in your research?

GHARAVI I still have a lot of questions about frictionlessness, namely in the ethics of design and user experience. These days I use my Apple wallet to get on the subway. I don’t even need a credit card anymore. The pain points have been removed. As a consumer I often wonder how I can reintroduce the pain points, just to have a semblance of agency. Consumers have long now been in a subscription model. That frictionlessness created by the move from ownership to subscription brings about a new dissatisfaction. I’m trying to think about what that looks like. But on a bigger scale, and maybe a darker political model, in the last twenty years we’ve gone from Napster and LimeWire to Spotify, from a promise of technology as a communal and collective good to a reality of corporate authoritarianism, for lack of a better term. It’s hard to even identify a left and a right anymore in that discourse. The person—or user—has been all but obliterated for the sake of a “rational” corporate authoritarian, both politically and in consumer terms. This model does not even assume democratically shared power or democratic collective ownership anymore.

KHALILI Radio AlHara is a media platform that we have been working on to try to create a communal space outside of social media. What kind of spaces can we open and how do we work with them? How do we understand their relation to these corporate worlds as well?

With Dayra we’ve been trying to push against the speculative economy of crypto. If crypto is a trustless structure, how do we then bring it within trust structures, not to create speculative financial instruments, but for actual social uses? We are trying to move away from digital assets. The idea of Dayra is about minting the act of sharing. We want to create ways for the community to store value and exchange that value for the future.

Throughout the whole process, Abed has insisted that we do not become a company producing a product—a crypto coin—and trying to sell it and create capital from it. We want to ensure not only that we work ethically and critically, but also that the structure itself does not get corrupted by the structures of the blockchain economy that it’s trying to work within. How do we work with the blockchain without reproducing the market that we’re trying to push against?

ABED The problem with all the cryptocurrencies and blockchains out there is that they have reduced the value of this technology spectrum to the least significant aspect of its potential value—money. Proof-of-work is super resource intensive, but we are, too. There were trials in Sweden to set up a mining farm and harvest exhaust heat to recycle in the district. There are a lot of things that can be done, but unfortunately they don’t fit the current financialized system. They don’t make money, certainly not in any quick way.

Imagine this scenario: I live in a tent. Yazan lives in a tent next to me. He has a hammer. Monalisa has a nail. I want to hang something in my tent. If Monalisa gives me the nail and Yazan gives me the hammer, I can use them. Then later I can help them when and as needed, because I’m obliged by my natural positivity.

We’ve had a lot of discussions about minting value, and we still need help to materialize its ultimate form. We think of Dayra as communal, in the sense of knowledge. I tell my fifteen-year-old son that when he’s going up the stairs and sees someone who needs a hand, it’s his responsibility to offer it: to utilize the resource that he has right now to help others. Having knowledge of art and technology puts a responsibility on our shoulders to use it for the communal good.

This is where the value of knowledge manifests. If you don’t spread it, if you’ve invented something new and you’re sitting on it, where is its value? Value can only manifest once knowledge is transmitted. That’s what Dayra aims to tokenize—knowledge and the skills that emerge from it.

KHALILI Digital spaces have been coopted by corporations, and we want to reclaim them as communal ones. The commercialization of public spaces has influenced our political engagement and hampered our ability to form collective knowledge, as opposed to individualized knowledge dependent on our locality or identity. In 2018 I made a photography project titled Holding White Paper as a critique of the circulation of images, particularly how politics gets corrupted within social media, through turning any political statement into an empty signifier that then can be coopted by any movement. I saw an image of Selma Hayek in Cannes, holding up a piece of paper saying “#FreePalestine.” Then I saw the same image, with the same paper, but this time it said “#BringBackOurGirls,” and it was in relation to the kidnapping of girls in Nigeria by Boko Haram. Then I saw it again in relation to another struggle. This is how images become empty. Holding any political statement is like holding a piece of white paper. There’s no origin, just the movement of topics.

That’s one approach to social media. Radio AlHara is a kind of affirmative critique. How do we actually claim back the internet? How do we move away from the data harvesting that happens within our community? By running the station, we learned about the huge network of online radio stations that work together on a different economical structure that is mostly non-competitive, supportive, scalable, and interconnected. There I saw a different internet than the one of social media as we know it now.

GHARAVI I think Web 2.0 held the promise of interconnectedness and authenticity, and one of the outcomes of that has been this conflation of the internet with social media. For many people, the internet is social media, or a self-enclosed app. I’m pessimistic about social media as long as it is in the hands of two or three corrupt corporations, because it has shown itself to be the site of endless extraction, whether we’re talking about privacy at Facebook or AI-powered imaging at Google. We’re still trying to understand what web3 does. But I think the promise of web3 is non-fungibility, and the re-creation of a sense of location. Is that sense of location satisfying? Balaji Srinavasan wrote a book called The Network State (2022) in which he advocates for a startup society, with the exchange of sovereign cryptocurrencies instead of money, and the execution of smart contracts instead of law. If you like the country you’re in, you can keep it. If you don’t like it, you can start your own, because the assumption is that space is infinite.

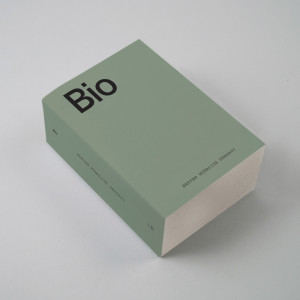

In creating Oil Research Group (ORG), I’ve been asking whether data is truly infinite in contrast to fossil fuels, which we know to be finite. I hypothesize that data is not infinite, or maybe it is in the sense that it can be endlessly created, but that it is still precious. If we were immortal, then we wouldn’t know the value of the present moment. Why would it matter? We’d live forever and forever. This debate between the finitude of the meat body and the infinitude of the data body was also at the heart of Bio (2018), which I created over the course of a year. Funnily enough, much of that year was spent in Ramallah. At the time I was looking for the gap, the suture. My dissatisfaction at the time with Twitter was that I couldn’t find a gap or suture—just a flow. I was always being stored. I was always being saved. I could never delete myself fully. Even if I were to delete a tweet or indeed my account, there would still be a metadata or trace. Bio was successful in so far as it found the gap. There was no API in the bio line of Twitter. I realized I could update that field every day without the corporate structure having metadata of it. I find that’s getting harder and harder to do. There’s a famous understanding of the internet that if something is free, you’re the product. I want to push back against that a little bit. I don’t think that you’re the product, I think that you’re the fuel. I’m currently looking at exhaust—the material outcome of fossil fuels and gas on the one hand and data and the material outcome on the other, which is a lack of privacy, an assumption of authenticity, which may or may not be true. As you said: is Salma Hayek really holding up that which the picture shows her holding up?

From exhaust to exhaustion—this collectivized sense of apathy, boredom, and deep depression. There’s what, five billion people who have access to the internet globally, and all have been forced to live our lives online for at least two years because of lockdowns. What kind of subjectivity has that created? What are some of the ways of that exhaustion being fuel? What are some of the outcomes of that—politically, artistically? What does that look like? What does that feel like? That is the direction that I am now exploring.

ABED There are a lot of positive promises of web3. But as you said, nothing you do on the internet can be deleted because there is metadata for it somewhere. There were positive purposes for this, one of which is audit trails. There are systems that require us to know who did what when, and what changed. Audit trails helps you figure out what went wrong so you can fix your problems and optimize your processes, to enhance services and performance. But this got twisted into creating a forced digital twin for everyone that we can’t get rid of and in many cases has no resemblance to our true being. Now web3 promises a solution but has its own problems to deal with first.

Are there ways to do something positive with it? One example is in the Netherlands, where they used web3 to register refugees, distribute vaccines to them, and confirm that they have access to what they are entitled to and need. So there are good uses and there are bad uses. Is it going to solve all the problems? No, I think the source of all evil is humans. Technology is not going to clean that up unless it wipes us out. Sorry to out-bleak you, Monalisa.

GHARAVI That you have been able to conceptualize and collaboratively imagine something like Dayra under fairly insane conditions is itself extremely valuable. I’ve learned a lot from talking to you and reading about it. I want to make the case for projects that are created and exist conceptually until they find a home or until they find collaborators.

KHALILI We are always open for people to come and join us in thinking about how Dayra will develop. This has been our way to build an ecosystem. This is how we imagine data as a community rather than a technology only. There is some tension with me coming to it as an artist and Abed coming as a technologist. That kind of pushing of language, structures, and approaches is what allows us to rethink these structures established as technological ones and push them toward becoming social structures. This is where politics begins to come in—in the push, in that tension, in these kinds of discussion. The more people join us in thinking about Dayra, the more tensions begin to happen, and these tensions create the critical ecosystem that the technology needs to function. It’s a twofold process. We don’t want to make a product and then test it with the community. It has to be worked within the product itself so that it totally functions when introduced to the bigger community.

—Moderated by Brian Droitcour