Ryan Kuo & Zach Gage

The two artists discuss how recent work explores their complicated relationship to ownership and the blockchain.

The mainstream perception of technology largely places it in direct opposition to the human: digital versus physical, screens versus bodies, machine-driven automation versus organic spontaneity. The performance-rooted practices of artists such as Sougwen Chung and Operator explode this binary. For the past decade, Chung has been working on Drawing Operations, an ongoing series of drawing collaborations between herself and successive generations of robots named D.O.U.G. These collaborations are performed in front of a live audience, a way to demonstrate what Chung calls “the beauty and fragility of both human and machine.” Ania Catherine and Dejha Ti, the duo behind Operator, create experiential works that draw on different technologies, from projection mapping and AR to blockchain. The choreography of movement—whether that of the artists or audience—is also central to their project of integrating the human body and advanced technologies. In this conversation for Outland, the artists explore how their different professional backgrounds have informed their creative approach, discuss key projects, and reflect on what terms like “technology,” “performance,” and “the body” mean to them.

SOUGWEN CHUNG When I think about being an artist, I think about communication—it’s a way of expressing and communicating essential truths in the world that can take the form of many different mediums, whether more traditional mediums like drawing and painting and dance or other mediums like engineering and research and language.

My background is actually as a classically trained musician—a performer and a violinist. That really shaped my understanding of the expressive gesture, of music and sound as an abstract form, and of the artifact of that being a recording of time. I was also very much steered by my experiences on the early internet in the ’90s. And I have to give credit where credit is due: my father’s an opera singer and my mother’s a computer programmer. So I grew up with those languages of both computer science and performance. That all dovetailed into an interest in interactive media, which is how my career in art started.

I’m really glad to be speaking with both of you because I feel like in the space of interactive media, movement and performance is not always foregrounded.

ANIA CATHERINE In the same way that you grew up with music, for me that was the dance studio—I trained in ballet, jazz, modern, tap, all of it up until college level. I always took it really seriously. There were kids in classes who were goofing off and I always felt like we were all in the dance studio saving the world. It felt like more of a calling or some sort of sacred task or mission.

I ended up in a pretty artistically conservative college dance program, where they would grade choreography and were very much trying to reproduce subjects that could easily be employed by existing contemporary dance companies. The department was not prioritizing being a place that would allow artists to create new movement techniques. I dropped out of that program and started studying political science and gender studies instead, while continuing to explore performance, dance, and movement on my own, collaborating with filmmakers and other artists.

I did a lot of work with untrained performers, leaning more into pedestrian movement, movement that looked like life, or that felt like it was actually coming out of me. It felt like an excavation process, trying to unlearn all those years of discipline and training in order to find something real that emerges from my own body. I was creating my own performances and films when I met Dejha.

DEJHA TI From a young age, I was constantly sketching, drawing, painting, sculpting. My first interaction with any kind of digital medium was a TYCO video camera. The camera was tethered to a VHS player, so I could only film weird stuff in my room. I also had a TYCO audio recording device, the one Macaulay Culkin uses in Home Alone. I’d duct tape the recording device to a remote-control car and then drive it around recording noises. Once I got to high school, I started to experiment with photography and Photoshop and HTML.

I wanted to go to art university, which is probably the worst news a parent can hear. I found this multimedia BFA program at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. The director of the program was very persuasive to unconvinced parents. He said that anyone who graduates from this program is going to be employable right away. So my parents were on board and I got into the school.

We learned filmmaking, sound engineering, interface design, website design, game design, and interactive installations. It might sound like “Jack of all trades, master of none,” but I reject that view. Having access to these different mediums really set me up to express a concept in the way that it needs to be expressed.

In the program we often talked about contextualizing multimedia within the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk—Wagner’s term for the total artwork—because it’s not just about using many mediums in a single artwork, but instead creating an artwork that is a singular experience. The medium used is just the right delivery mechanism, the best vehicle to serve the concept. I think of that when people use the term “art and technology”—why do these two categories need to be separated?

After university, I did everything possible to not get a job. To make money I decided to offer my services to people and companies who wanted to use new technologies but didn’t know how. I had a multimedia studio that created webcasts (livestreams), interactive installations and apps.

CATHERINE Wharton School of Business was Dejha’s first client.

TI Yeah. I really just wanted to make art. I had two lives at that point, one funding the other one, but I got to experiment a lot because I had access to resources and scale through my commercial work. But at some point, I had to just fully surrender to being an artist.

CHUNG That’s a powerful moment, I’ve had that as well. I was in interaction design and media, also working with a lot of real-time motion graphics and experiential storytelling. As you say, it’s like getting paid to learn, and I think a lot of people don’t realize that there’s a lot of power in being paid to learn and service something that isn’t your own message—and then also making the decision to really commit those talents to something that does bring personal truth and joy into the world.

Thinking about our different backgrounds, it seems to me that there’s a rebellious streak that brings us together. Ania’s rebellion against the script of traditional dance is something that I really relate to in terms of being classically trained in instruments. Perfecting the script of what came before was not particularly interesting for me either. Dejha, you mentioned this rebellion against the unnecessary binarization of art and technology and the separation of different mediums. My ax to grind is the binary of human and machine. Recently I set up a studio, Scilicet, which is very much a work in progress but I’m thinking about ways that I can create support for other artists to create conversations subverting all binaries, whether through collaboration between human and machine or otherwise.

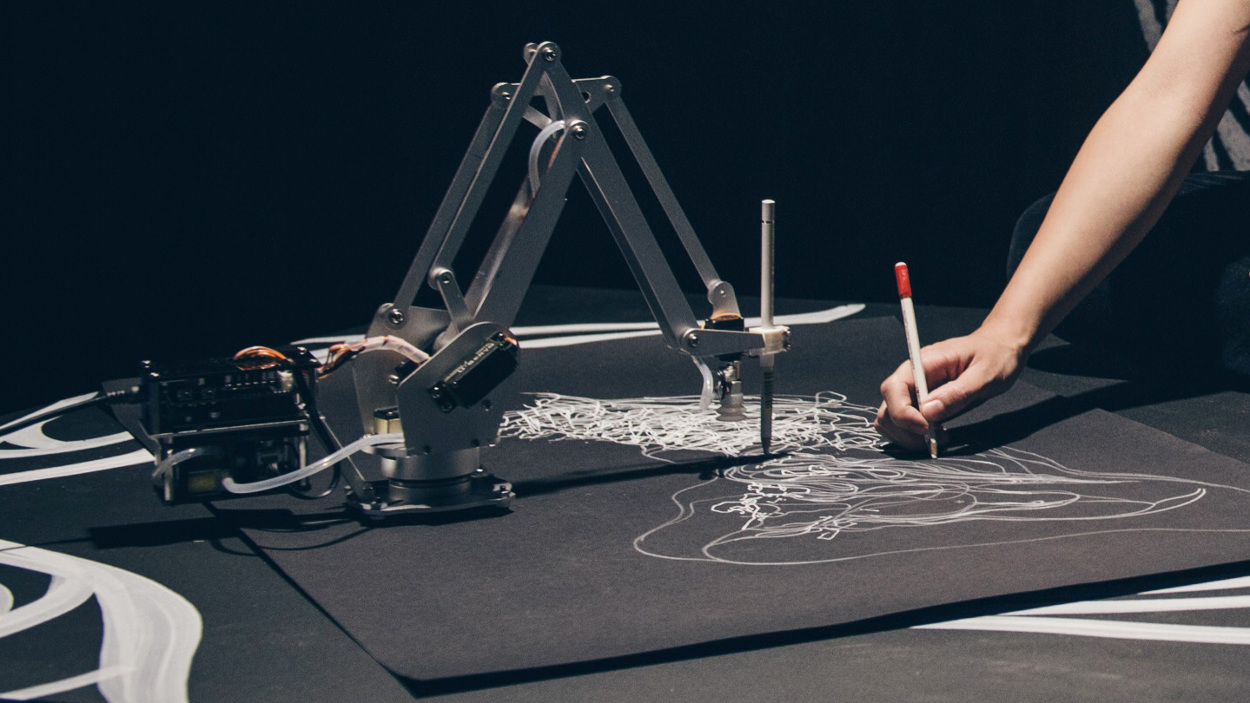

Even though I’ve been speaking about my Drawing Operations project for quite a few years now, I still find it to be rife with speculative potential. Drawing Operations Unit: Generation 1 (2014–15) was the watershed moment for me moving from immersive media and projection mapping and installations to the performance world. Following a curious instinct, I built a machine, a robotic arm, and then sat with it in a black room with a spotlight, drawing what looked scribbles to everyone. I set up an overhead web camera to trace the movement of my pen and the robot mimicked that in real-time on the canvas.

With its integration of the human catalyst in a technological configuration and a performance context, that was really the project that started it all. It’s a journey I’m still on almost ten years later.

CATHERINE I love the emphasis you made on putting yourself literally under the spotlight, drawing. It’s such a powerful thing.

I think you can still feel a bit of our service background in the installations we do. Some people particularly comment on the polish of the production. We love conceptual art but they seem to think we can’t be conceptual artists because with conceptual art the idea is the art and the thing itself doesn’t matter. We’re obsessed with the concept but also the execution—every detail of it.

CHUNG There is such a generosity in presenting the work in a way that pays a lot of attention to detail, and how it’s experienced by an audience.

With Drawing Operations, through the spotlight and the scribbling and the barely functioning robotic unit I was able to unlock this idea that the finished product isn’t the only form of communication! There were also a lot of concerned glances from people thinking I was having a mental breakdown. But it was important for me that the struggle and fallibility of the system was on full display—to put it another way, it was about showing the beauty and fragility of both human and machine.

CATHERINE I love it. The best performances can be mistaken for a mental breakdown.

Line Scanner (2016), our first work, actually emerged from a job. We literally shot it on the set of a corporate job while everyone was on a lunch break.

TI That is true. We were in an airplane hangar studio in LA and I had the idea to rig a projector on a crane 40 feet in the air, and map my animations onto the floor where Ania was improvising movement. It was the most obvious collaboration we could do, the least interesting thing we could do together—so we got that out of the way early on.

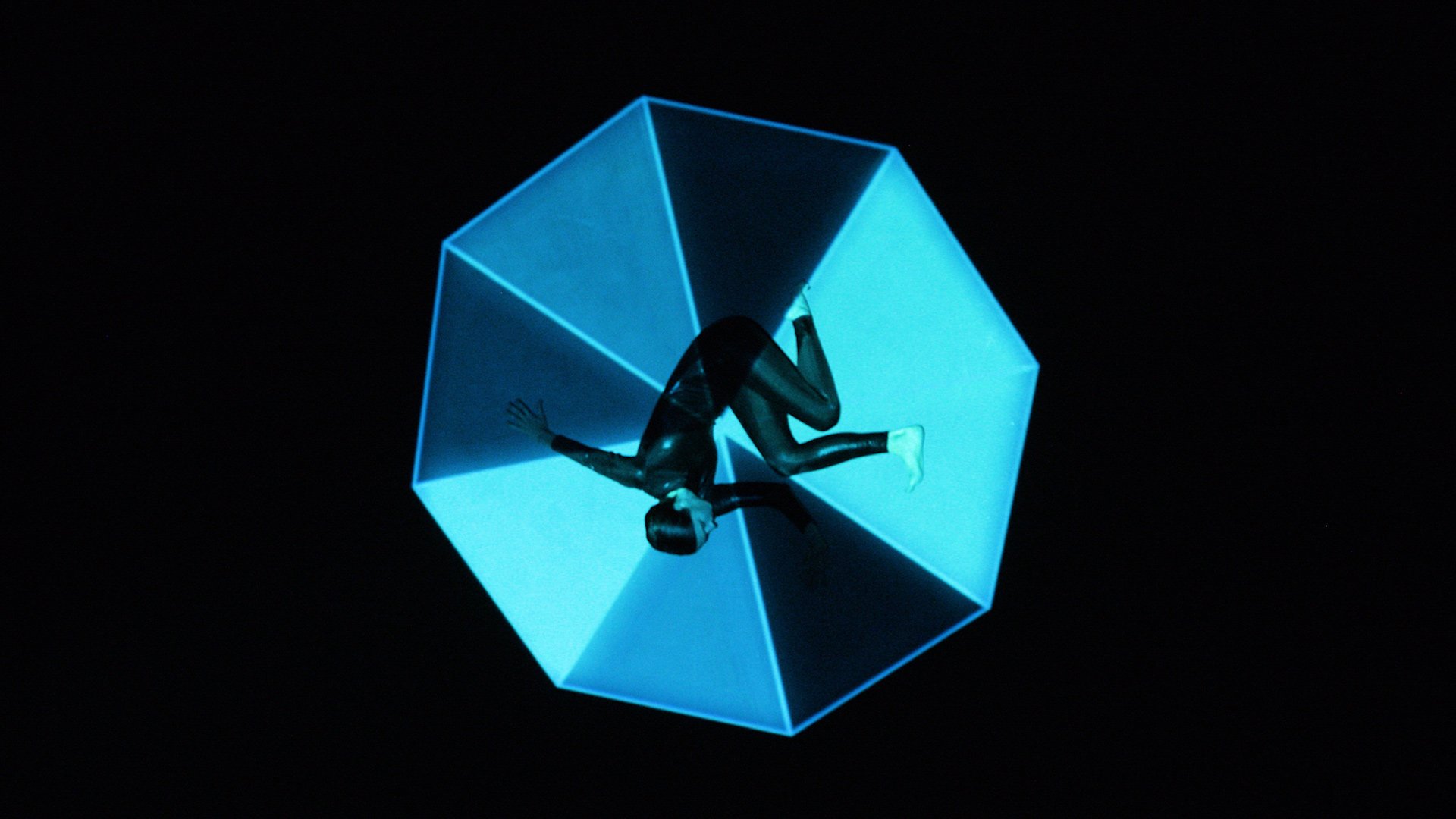

During this time we still had our own practices, but were creating more and more together and then all of a sudden one day we woke up and we had a full-blown collaborative art practice. One of our first major works as Operator was On View (2019). It was commissioned by the SCAD Museum of Art. They wanted an immersive, experiential artwork for the museum.

CATHERINE We wanted to create an artwork for that location that was site-specific both physically and psychologically.

TI Yes, and to implement the pillars of our practice into the artwork—performance and the human body; environments, a digital-physical hybrid; and intentional integration of technology—all in the service of an experience.

We thought, “How are we going to implement a performance in a three-month museum exhibition in a sustainable way?” Could the audience not only be a participant, but also the performer? We designed the installation so that the audience-participants watching other audience-participants interact with the installation becomes a live performance element—their interactions are choreographed so that others in the installation experience a curated relationship of bodies moving through space. This worked well conceptually because the piece is about how selfie culture and extractive technologies have changed the way people experience art. The audience-participant literally becomes the subject of the artwork and is put on view.

CATHERINE I think there’s a link between On View and the way Sougwen’s work is exploring these false binaries of human and machine, in which the machine is strong and rational and the body is soft and fragile.

TI For sure. Although people think of technology as strong, it’s actually quite fragile, especially if you’re working with experimental technology—most of it is not going function months or years from now.

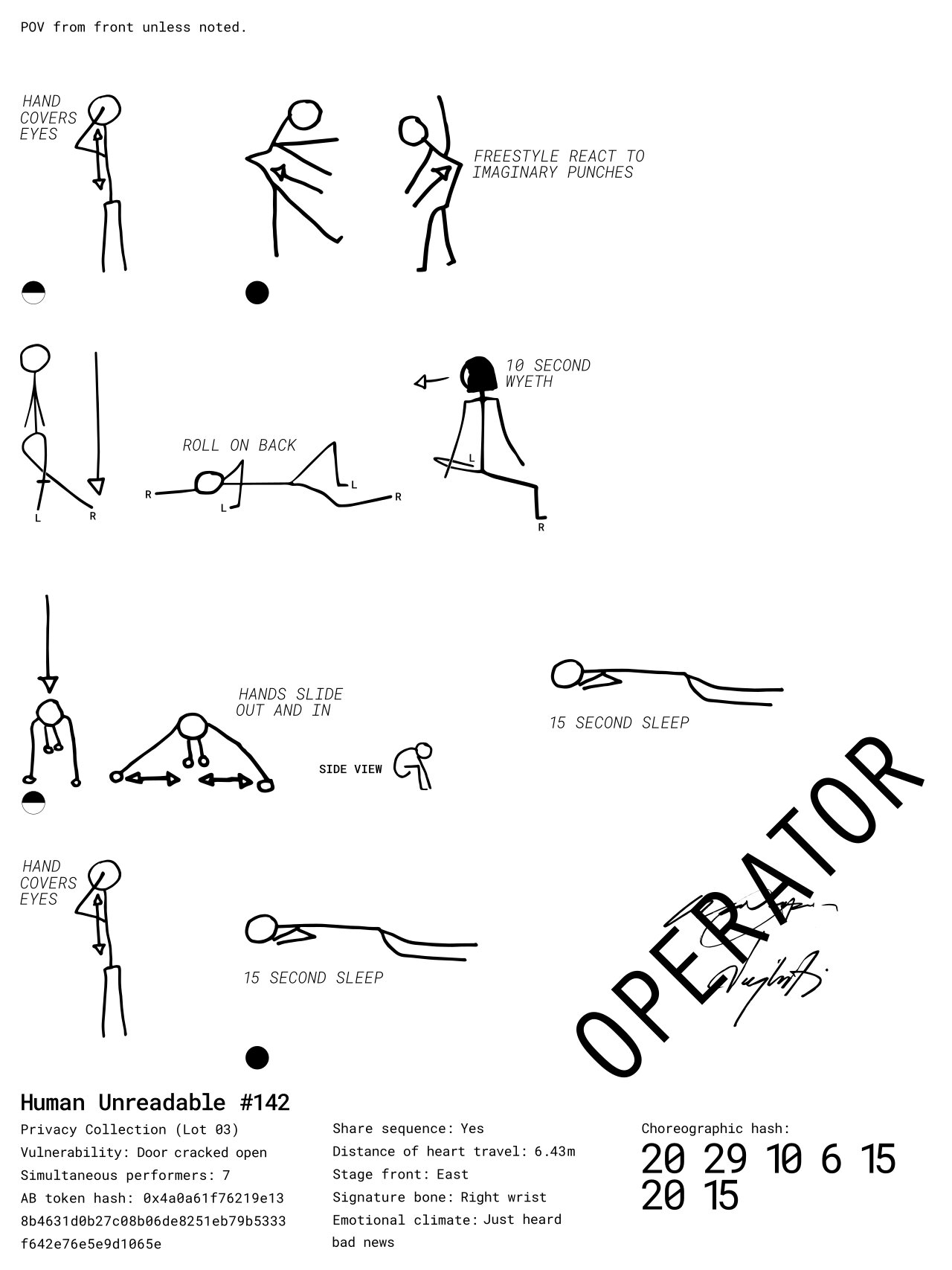

With our practice the work needs to be art, but the work also needs to work. We experienced this with Human Unreadable (2023). The artwork we created was made of the limitations of two technologies—the human body and long-form generative art. How do you create a movement library, capture the movement library in high resolution data, downsample it while preserving the essence of the human and the moves, store it on-chain, and implement a choreographic algorithm that then outputs a unique tokenized sequence that also can be performed live while still maintaining human expression, still being art—not just a tech demo?

I think it’s a wonderful challenge. We think of the human body as an essential aspect to Operator. There is this chemical reaction that happens when you try to integrate the body and technology. It’s kind of like oil and water—it’s like they don’t want to fit together.

CHUNG What I love about the Operator work is what you said about it needing to work—like these are all materially functional pieces. I was recently talking about this with Christiane Paul, who curated the Harold Cohen show at the Whitney Museum in New York, and understands the complexities of installing robotics works in the exhibition space. Every generation of Drawing Operations is constructed through the technical possibilities of the present. The sensor technology needs to pick up the movement of my drawn line in all these different ways. I think it’s a testament to the value of art practice being able to hybridize art and engineering, because your works and mine are both really embedded in both languages— work that needs to work but that also has to be art. I love the power that artists have in informing how these technologies develop—building features that would never take place in the space of a research lab or a more commercial context.

Although sometimes… I actually don’t feel that the work needs to “be art.” For instance, I think there’s value in letting something just be. Even though my artifacts are paintings, a medium almost synonymous with art itself, I still question whether or not the artifacts need to be art, for myself. Perhaps to me it’s art like found art is art—accidental, contextual, in place. But that’s another more speculative conversation for another day.

In terms of the human element, in the beginning Drawing Operations was in a way a reaction to the idea of the human element in interactive media as analogous to Perlin noise. All my interactive media contemporaries would say, “If you ever need to do a test without an audience just throw Perlin noise in the system and it will essentially function the same way.” I had a very spirited discussion with Mario Klingemann in Munich about how I didn’t believe that the human element—perhaps because of my background in music—could be replaced by Perlin noise. It’s not an accurate facsimile of what the human can do. There is the fragility of the human body but also the mastery and the craft and the true expressiveness of the performer.

CATHERINE The idea of the human just being this dash of randomness or chaos is strange framing, particularly when you think about the sophistication of the body as a functioning machine. I think people are probably threatened by it. Like, it’s right here but it’s basically also the deep sea. There’s so much we don’t understand about it. I think people who want answers, control, and to map the world don’t know what to do with that level of unknown.

CHUNG It’s interesting that many of these modern technological apparatuses seek to control the human body and how it moves through space, how it expresses itself. It perpetuates a certain type of ethos—sometimes turning into a cult of optimization and quantification.

CATHERINE You said that your work with the robotic arm is now going on ten years. What has evolved about it and what stays the same?

CHUNG I think of it as an ongoing project. With each generation I endeavor to explore a different theme that I’m inescapably drawn to—that I either find exciting from a engineering point of view or that is conceptually catalytic in a way.

Generation 1 (2014–15) was focused on mimicry—this idea of relating positional data in real time to create an operationalized pseudo-automatic image that foregrounds improvisational gesture. I appreciated the leap of faith that the New Museum and curator Julia Kaganskiy took in the early days of the work, providing a space for me to share a piece like that. Generation 2 (2015–2017) was about memory—I trained two decades of my drawing data on a recurrent neural network and used that to create a machine collaborator that would respond to my inputs in the way that I would. It was exciting to debut the work at the invitation of Hatanaka Minoru in Japan at the NTT ICC Open Spaces show. Generation 3 (2017–2018) came out of an interest in swarm robotics and crowd data, using the crowd as captured by public cameras as an input for the multi-robotic system. It was a joy to install the work so many years after the fact, at the “Imitation Game” show at Vancouver Art Gallery, curated by Bruce Grenville.

Generation 4 (2019–21) centers my own biology through human-machine feedback loops and my own bio signal. It came about during the pandemic. Again, I’m grateful to the curators at the Schaulager Foundation for providing me the residency and time and space to explore stillness. I didn’t particularly feel like drawing anymore and I really honed in on my meditation practice, which led me to think about ways that I could read my own bio signals as another form of movement. I used my alpha waves, which are heightened during meditation, as a trigger for robotic painting—which in turn enforces my ability to get into a deeper meditative state.

Generation 5 and Generation 6 are exploring ways that I can build different types of machines that are derived from organic silkworm material. That’s very much still in progress. I actually have my silkworms right next to me right now.

TI What is particularly interesting to me about Generation 4 is how you define a different version of movement. It’s not just about the movement of your body; you’re asking what other types of movement there might be. In this case it’s the movement of the meditation. In our practice we also think about stillness as a movement.

CHUNG It’s my Cagean 4’33”! In 2021, as part of a commission by Claire Webb with Berggruen Institute, we performed that at the Bradbury Building in Los Angeles and I meditated with the machines for a full three minutes. I’ve never felt so creatively charged. I love how activating a creative idea through performance can do that, and I love the idea that presence is generated through mechanisms of refusal and delay.

There’s this book that influenced me as a younger performer which I returned to in preparation for this conversation. It’s called Archaeologies of Presence (2012). There are so many amazing quotes on it. Here’s a shorter one I picked out earlier: “In theatre, performance and visual art, the experience of presence has often been linked to practices of encounter and to perceptions of difference and relation with something or somebody, as well as the uncanny encounter with one’s own sense of self.” I think it links in so many ways to what we’re talking about. We shape the language of performance and shape our own senses of self through these technological mediums. It’s not just performance, of course, but perhaps the landscape of artistic practice in general. By breaking apart the more traditional frameworks or expected modalities of technology, we’re opening up our practices to a larger dialogue around art and technology, or human and machine.

CATHERINE Especially in the dance world, it’s almost like technology is seen as the opposite of the body. Because dance is such a visceral embodied art form, it seems that most people think the only thing technology could do with dance is interfere or distract. Of course, I have seen performances where someone was just like, “Let’s do something cool with tech and put this string of lights around a dancer.”

TI Or technology projects adding dance or performance as an afterthought.

CATHERINE But also, what you said about the artwork incentivizing you getting to a deeper place within your own mind, this is something that we think about a lot. How can we undo this idea that technology is always an interference with our sense of embodiment or our understanding of ourselves? And in what ways can it be used not to get in the way but somehow to become a partner in getting deeper into our bodies?

CHUNG Like a feedback loop, right?

CATHERINE Exactly. For instance with Human Unreadable we were thinking about how we could use long-form generative art and crypto art market speculation to get a bunch of collectors moving their bodies. We literally have videos of collectors in their backyards interpreting their choreographic score.

I don’t think very many companies or labs are trying to use technology in that way. So I love that we’re trying to push its limits, to the kinds of ends that might not make anyone money but add a lot of value to the experience of life.

TI Right, in contrast to how we experience technology every day—devices, notifications and addictive interfaces pulling us out of our bodies, out of the present moment. We are real-time, but we are not present.

CHUNG It’s interesting for me to hear what you both push up against in terms of how technology is regarded in the field of performance and movement. Even though I think of my own practice as movement, sometimes it’s approached as image. People are not necessarily distracted by the artifact—the drawing or the painting—but the artifact is the entry point.

What I push up against is the idea of technology as automation, especially with something like a drawing with a machine, which can be infinitely replicated. While sometimes it can feel like all anyone wants to talk about is AI in this current cultural moment, I always want to remind people that the point of using AI is not to erase the history of drawing, painting, and movement. It’s about reinvigorating it.

In fact, while I’ve been stepping a little bit away from performance lately, I feel like this conversation is reinvigorating my own interest in it—this idea of activating presence through performance, but at the same time holding something back and subverting expectations. Maybe the Archaeologies of Presence book articulates it best: “Not only does the notion of presence in performance imply an absence, but that absence itself is the possibility of future movement; so paradoxically, presence is based not only in the present, but in our expectation of the future.”

—Moderated by Gabrielle Schwarz