David Horvitz & Mendi and Keith Obadike

The artists discuss how the performances they staged online have impacted their approach to working in public space.

Takeshi Murata and Rafäel Rozendaal have been working with emerging technologies in their respective practices since the 1990s, and have both exhibited with major galleries and institutions. But recently they have taken advantage of the new opportunities NFTs have created for multimedia artists wishing to transcend the constraints of the white cube. Both have launched successful projects on Art Blocks: Murata’s Kai-Gen and Rozendaal’s Endless Nameless. In the conversation below, Murata and Rozendaal discuss how their art has adapted to developments in technology over time, the importance of community and collaboration to success for digital artists, and their predictions on how NFTs will further support the creative process.

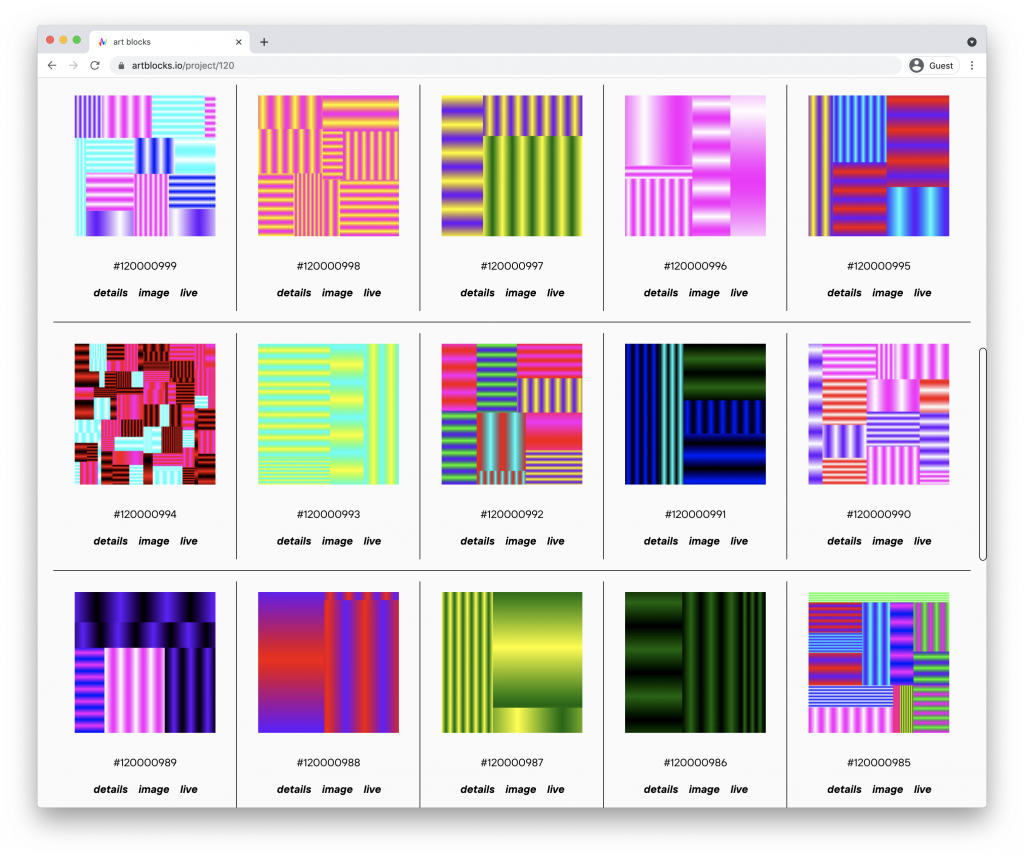

ROZENDAAL I’ve been making code-based moving images since 1999. They were anchored in domain names, and that’s how they were sold. When NFTs came along, I hesitated, but then I jumped in—they’re a good fit because my work is about making moving images without a beginning or ending. I’ve always thought of the internet as a place where you can stare for a long time or move on very quickly, as with paintings in a museum. The idea of NFTs being digital paintings, these objects—that’s where I was coming from already

I’m interested in artists using (or misusing) materials in strange ways. Your way of working is quite different from mine. I appreciate your technical mastery combined with a sort of misfit quality. Your work doesn’t fit into categories like special effects, painting, classic animation, or filmmaking, and I appreciate that you don’t easily fit in anywhere.

MURATA Being half Japanese and growing up in Colorado in a predominantly white neighborhood, I started to feel like I didn’t exactly fit in when I was in fifth or sixth grade.It was compounded by going to Japan and not totally fitting in there either. I wonder if that is connected with this feeling of not totally aligning with a specific genre. I see that in your work, too: you were making the works with domains so early, doing things that people didn’t know how to place at all. You say you sold them, but I imagine that was very challenging within the gallery context.

I graduated from RISD in 1997, and film was still the major to do if you wanted to work with animation. We worked with 16mm film, and these massive Oxberry cameras. If a gear got stripped, there was a machinist who would fix the parts. I knew I couldn’t afford this equipment and film after I graduated, and I realized I would have to move onto computers if I wanted to continue to produce my work independently. I taught myself Shockwave for Director.

Since I started showing in galleries about fifteen years ago, I’ve been working toward deadlines. I discard a lot of work to get to this finalized, precious thing that would be shown. I had the sense that many of the things I was throwing out could very well have been better than what I thought was what I wanted for the show, but I just didn’t have any way of showing it.

ROZENDAAL If you’re a painter, it’s very clear: you’re hoping to show at a gallery. But with moving images—especially in the nineties—there was a huge spectrum of possibilities, from video games to music videos to art installations.

If before the lines were blurry, now there are no lines. Galleries were always open to moving images, but you were at a disadvantage. The whole infrastructure of the gallery is made for painting. They’re easy to photograph. They’re easy to bring to fairs. In the NFT world, everybody’s like, “Oh, it moves. That’s even better.”

With NFTs, the speed at which you can produce work, publish it, and sell it is helpful. When I think back to my earliest times making work on the internet, there wasn’t money in it. We were doing it for fun, and we could afford to because we were young. It feels similar to this current time, where you finish something that looks cool and send it around to see if anyone is interested. Back then your friends might say it’s cool, and that would be the end of it. Now if people enjoy it, they can buy it, allowing you to work in that direction further.

MURATA That’s what I find so incredible about the NFT world: it’s transparent, and everyone knows what everyone’s doing and making. In the traditional art world, there’s a side that no one talks about. Everyone assumes that artists represented by high-end galleries are living this lavish lifestyle, but that’s often not the case.

ROZENDAAL The difference in your understanding of the art world three years before you graduate art school and three years after is huge. My perspective changed when I moved to New York. The Netherlands, where I’m originally from, subsidizes the art world. The market doesn’t play a big role. That’s why you see a lot of new media art coming from the Netherlands. Someone told me very early that the art world only has room for “a hundred freaks” that do things other than painting—you can have James Turrell, Marina Abramovic, and ninety-eight others that do things that are hard to sell. Even those artists have to find their flat work, something to hang on the wall, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

MURATA It was similar in the film world. There was a commercial aspect to it. There were producers and production houses coming to see the work. It was implied that a short, experimental work would be a stepping stone to a 90-minute feature. For me it’s very clear that NFTs are the end of experimental animation work being some sort of in-between thing on the way to features or flat work.

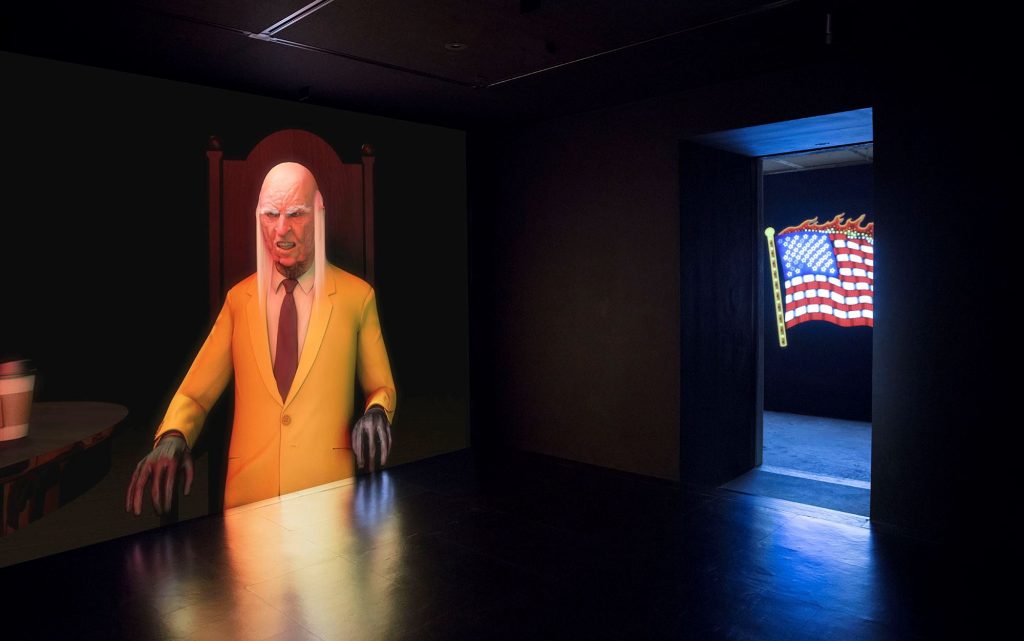

For example, I just released Kai-Gen with Christopher Rutledge and J. Krispy on Art Blocks, and I had access to incredible programmers and animators that I wouldn’t have been able to collaborate with in the past due to cost. Christopher came to me three months ago—forever, in NFT time—with the idea of putting 3D figures on-chain. We used three.js and a system of modeling developed with the programmer in Houdini. I sculpted with these custom tools, using primitives combined via sdfs, then exporting the sdf definitions from Houdini to GLSL code and a custom renderer..

The working process was organic for us too. We worked as one unit: I would work on a model, export it to the json file that J. would use, and he’d return the render. It was really back and forth, and fun. I requested features that Chris and J would implement. And it was a relief to not have to defend my choices to anyone outside of the team . That probably wouldn’t have flown in other venues.

ROZENDAAL When talking about NFTs, people sometimes use the word “screensaver” as a derogatory term: “oh, this is screensaver art.” I’ve had this long history of admiring screensavers as this long-forgotten form of moving image; I even curated a show about the history of screensavers in 2017 at the Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam. It’s a revolutionary form that has a complete language of its own, and was created primarily by programmers rather than by artists—it was a way of showcasing programming skills, and there wasn’t a high artistic barrier to entry.

It’s similar to what you’re saying about working on Kai-Gen: you didn’t have to write a long text justifying why it’s important. I sometimes miss that level of freedom in the art world—sometimes you just don’t want to explain why you make something.. The internet offers that freedom where there’s room for the subconscious and the vulnerable. If you were a comedian, you wouldn’t want to have to explain your jokes.

MURATA It’s interesting you bring up comedians. The goal is to make the audience laugh, and when that happens, it’s a clear success.

ROZENDAAL Comedians can write all they want at home, but they have to go to a live audience to even know if it’s funny or not. With NFTs, you can see right away whether or not something sells.

MURATA Thinking of the presentation context of works sold in the gallery is difficult, too. At the beginning, I had no visual reference for a collector’s house in the Hamptons, and even the biggest work I made felt dwarfed in the gallery. It’s nice to know that this work can be looked at on a phone, or a monitor.

ROZENDAAL Then again, we both showed work in Times Square. The fun of digital work to me is that it can be shown on any scale, in any context. I’ve always thought of digital works being flexible, and have treated composition as a programmable idea: a work that can fit any potential space. With physical work, you can’t just click a button to change its scale.

People appreciate the technology now, or at least understand it more, too. In 2006 I had the president of a telecom company come to an exhibition of mine and not know how to use a computer mouse. Now you have an audience that is fascinated with digital distribution and who understands animation software, different browsers, and code with varying levels of literacy.

MURATA I love the tech guys. It was amazing that J. [Krispy] could get the Art Blocks project down to 45KB to fit on the blockchain.

Actual limitations are easier to work with than self-imposed limitations. For me, I always have to have some limitations. If they’re not there naturally, I have to create them. If they’re artificial, you have to define and believe in them: you have to figure out why they’re there, and what their actual role is.

ROZENDAAL I noticed that you made a trailer for Kai-Gen that was more photorealistic animation. It reminded me of old video game packaging like Donkey Kong, where there were realistic color paintings that looked like Hollywood posters, while the game itself was 8-bit.

That kind of creativity and abstraction out of necessity seems to come at certain moments in history—when technology moves forward and there’s more resolution—and it seems like each generation has an interesting bottleneck that spurs creativity. There’s a materiality to those low resolution moments, for example, on one of those outdoor LED screens. There’s a physicality to it, even.

I also imagine that NFTs will provide a new space for independent animators. You could split a film into different segments, by minute or something similar, like what Kickstarter used to be. Now, though, you have a community that actually owns the work in parts.

MURATA I love that idea. Fractionalized investing in things is so exciting to me.

You could have people back your film for 20 USD and then possibly see returns if it gets syndicated. Before I’d been making 1/1 NFTs, and I wanted to be able to sell work for less. With the Art Blocks project, it was exciting to be able to sell each individual work for less money, with a larger edition size. But each work was unique. We genuinely weren’t thinking about the investment side of things.

I thought it was amazing that your NFT of Endless Nameless was the largest individual donation of anyone ever to Rhizome.

ROZENDAAL There’s been tremendous success in NFTs being used to raise money for different nonprofits and charities. Art Blocks as a whole generated almost 45 million USD in charitable donations last year. There’s a charity component to the sale system, where artists and Art Blocks decide on a percentage of sales to donate to charity before a launch. Other projects, like Edward Snowden’s NFT on Foundation, have also been successful.

The blockchain is transparent in the way that you can see what percentage went to charity, without the fanfare and ritual associated with benefit dinners or charity events in the traditional art world, where most of the money goes to catering and event planning. In those settings, artists usually have to give work for free and collectors get things at a discount. I started out online because I thought the traditional art world wasn’t for me. That’s what I recognize in the NFT space—young people building their own things.

MURATA I will say, too, that it has been such a welcoming space. I was thinking about the supportive energy in the way of curation with NFTs: there’s more of a collaborative aspect to it, perhaps related to ownership. Especially on chains with low or no gas fees, NFTs can be collected at all price levels, allowing artists to build large collections of other artists’ works. This form of connection and curating is really exciting to me. Just like how many of the artists aren’t from a fine art background, there’s not just a set group of people who got a degree in curatorial studies designating what’s important.I hope that it can sustain itself as more traditional institutions enter.

ROZENDAAL I do think curation is more important than ever with the abundance of creation. For example, music taste is developed by many influencers, as opposed to the art world, which has a few magazines and critics and curators that dictate the discourse. My hope with NFTs is that curators take on a similar role to that of DJs, or college radio stations, where there’s a distributed network of communities with different specializations and tastes, versus one central authority.

To me, it feels like the transition from the opera to recorded music. Opera strived to be the peak of human collaboration, bringing together architecture, storytelling, and hundreds of musicians working together at the same time. How can you compete with that with one mic in a recording studio? But because it was distributed, it took over culture, and recording quality improved over time. Even if the quality of recorded music was limited in the beginning, the distribution gave it so much more opportunity to touch more people. Eventually, recorded music ended back at the same scale as the opera in the form of stadium concerts and festivals. The museum will continue to exist, with the status of the opera house, separate from the zeitgeist—perhaps they’ll adapt to the digital, but I think our cultural experiences will happen more online. The museum will feel just as separate from art as the opera feels separate from TikTok.

—Moderated by Lauren Studebaker