A Map of Everything

Inspired by his research in theoretical physics, Eric De Giuli makes dynamic digital works that evoke nature’s emergent properties.

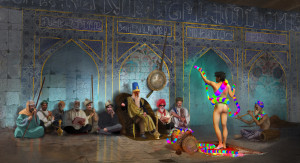

Blockchain technologies are often described as borderless, at least aspirationally. But even as more artists adopt NFTs, this notion of decentralization has yet to extend to visual culture. Certain visual languages and cultural symbols are more predominant than others. European paintings are often appropriated as contexts for signifiers of crypto culture, such as Afonso Caravaggio’s spin on Fredric Bazille’s The Artist’s Studio that replaces Impressionist painters and their subjects with Pepe the Frog, and Rishiraj Singh’s The Squiggle Charmer, which inserts Erick Calderon’s Chromie Squiggle, a generative doodle that became the logo of Art Blocks, into Jean Gerome’s Orientalist painting The Snake Charmer (ca. 1879). There are, occasionally, artists employing motifs and symbols of other cultures; Emily Xie draws on Chinese ink painting and Japanese woodblock prints in her generative art project Memories of Qilin (2022). Such attempts, however, are in the minority, and are often understood as deliberate engagements with the artist’s native cultural heritage rather than a universal lineage. This phenomenon is a continuation of problems in arts and culture that existed long before the blockchain. What would it look like to create a visual culture that is truly decentralized, that does not privilege one corner of the world over others? One artist building toward such a vision is Rimbawan Gerilya.

The horizon of our imagination is often limited by the realities we know.

Gerilya describes his practice as “Third World Futurism,” a framework built upon the stark income inequality in developing nations and how it affects relationships with technology among different demographic groups. Based in Jakarta, Indonesia, Gerilya lives a ten-minute walk from a neighborhood so densely packed that you can hardly drive a motorcycle down the street, and a ten-minute walk from an enclave of spacious mansions that boasts an equestrian center. Straddling both worlds, he has keenly observed that those from low-income backgrounds—himself included—learn to make do with inexpensive technologies of limited capacities, and teach themselves digital processes, as they may not have access to newer, better digital tools or industry standards. This in turn shapes their ability to envision networked futures and how their life can extend into the digital realm, as the horizon of our imagination is often limited by the realities we know.

Third World Futurism is also a response to movements such as Afrofuturism that is driven by an insistence on including and representing Indonesians and Southeast Asians more broadly in the development of the metaverse. Afrofuturism puts Africans and African-descended peoples and cultures at the center of speculative futures as a way of imagining alternate timelines where Africa was never colonized and exploited. Gulf Futurism, a term coined by Qatari-American artist Sophia Al-Maria, describes the phenomenon of rapid and near-dystopic developments in oil-rich states of the Middle East, reflecting on the present and illuminating the fetishistic relationship such states share with technology in imagining the future. Meanwhile, Sinofuturism, as articulated by Lawrence Lek, offers a speculative framework for engaging with the divisive portrayals of China’s investment in technological advancement, rejecting both China’s own heroic vision and harsh criticism from the West. Whereas Afrofuturism focuses on ideas of race and identity, Gulf Futurism and Sinofuturism reflect on attitudes toward technology in particular regions. While Gulf Futurism holds a mirror up to the present, Afrofuturism and Sinofuturism draw from the present to create fictional worlds. Taking cues from these adjacent discourses, Gerilya’s Third World Futurism gives visibility to Indonesia’s present social and technological realities and challenges his audiences to ask what kind of world they want to build.

Gerilya first adopted the term in 2019, when he created an untitled installation with recordings of sounds he encountered on a daily basis—such as prayer calls and dangdut buskers—and the kind of audioreactive visuals common at music festivals. It was an intuitive representation of the dual realities he inhabits: the physical world of his everyday life and his digital imagination. Like this 2019 installation, the imagery of Gerilya’s Third World Futurism can be read on two parallel timelines: one rooted in the present, one that projects into a future metaverse.

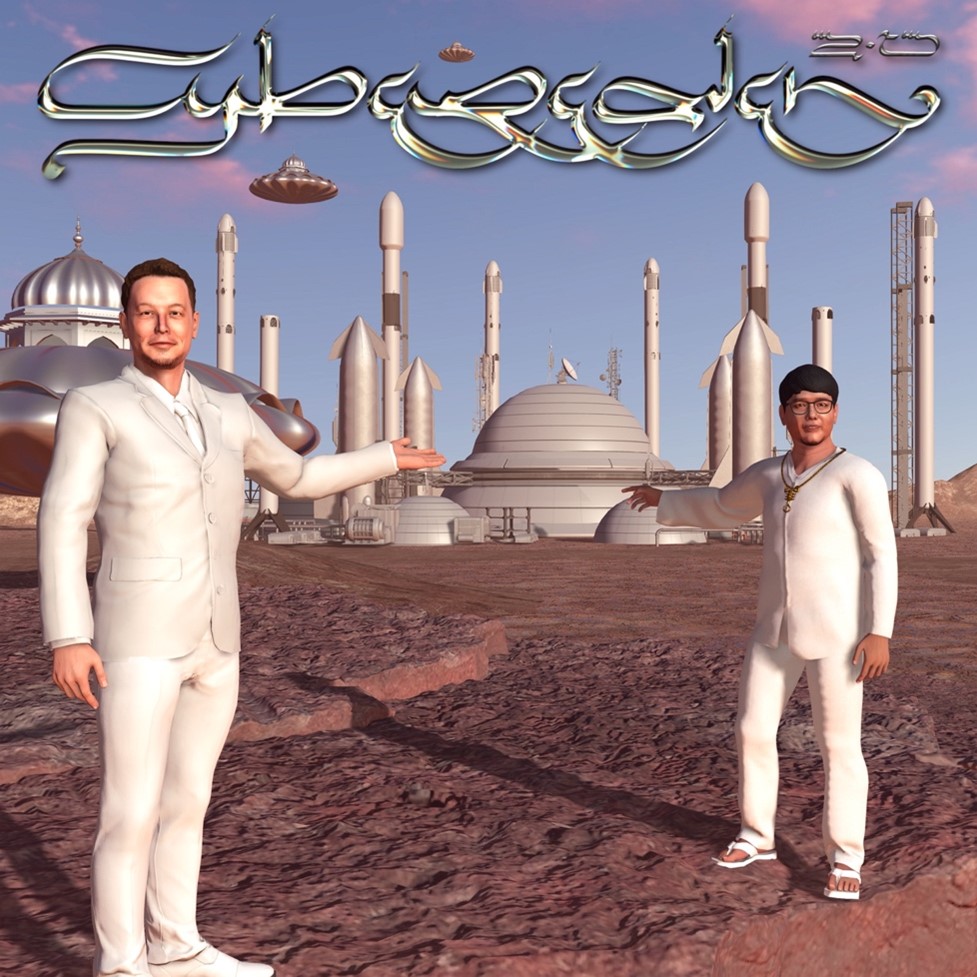

In Cybereden Server Farm Temple on Mars (2021), Gerilya and Elon Musk stand in an otherworldly landscape, both gesture towards a building surrounded by spaceships in the background. The tableau recalls how government officials or corporate leaders pose for press photos as the opening of a new development. Rendered as 3D avatars using Character Creator software, Musk is dressed in a white suit and tie and Gerilya wears a white baju, a traditional Indonesian shirt, and Zandilac slippers, a popular local footwear brand. The garb of Gerilya’s avatar represents how he himself would dress for a real-life formal event, thereby organically introducing an element of Indonesian culture to the work. The work riffs on Musk’s ambitions for space travel and interplanetary colonization. Gerilya imagines that Musk has built a civilization on Mars that is powered by machines running on artificial consciousness. The work prompts reflections on what space and artificial intelligence will bring, and who is included in or excluded from decisions about such ventures.

Gerilya continues the use of Zandilac slippers and other local cultural signifiers in David Kuproy (2022), his spin on Michelangelo’s canonical sculpture. Like the aforementioned Singh and Alfonso Caravaggio, Gerilya adopts the methodology of appropriation to extract and transform the meaning of a Western masterpiece into his own. The classical marble monument has been remodeled in 3D sculpting, with a newly added bucket on his right, a cement shovel over his left shoulder, and Zandilac slippers on his feet. Although he now has a few added accessories (including pants), David Kuproy maintains the classical contrapposto of his reference. Michelangelo’s David is the biblical hero who triumphed against Goliath, while Gerilya’s David Kuproy depicts a freelance construction worker in Indonesia, underpaid for labor performed in hazardous conditions. These workers are the invisible bedrock of our societies, and Gerilya advocates for their recognition by borrowing the heroic visual language of David.

Gerilya draws on the cultural and historical importance of his referent, while imbuing it with completely new meaning through his choice of medium.

David Kuproy is presented as a 3D object in GLB format and therefore can be interacted with and moved around while viewing. Viewers can determine the angle and orientation through which they study the 3D sculpture. They can zoom in or out. One can only look up to and revere Michelangelo’s marble David when standing in front of it at the Accademia in Florence, especially given its sheer scale and size. Like many digital artworks, the 3D object invites the viewer to share a more interactive and open relationship with Gerilya’s version of David. Gerilya thus draws on the cultural and historical importance of his referent, while imbuing it with completely new meaning through his choice of medium. This makes it quite different from parodic appropriations that focus on the former.

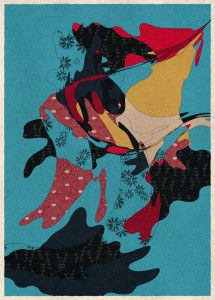

In addition to articulating potential future and present realities, Gerilya also illuminates what our digital worlds could have looked like if more of our present technologies had originated in Asia, or if more Asian contributions were better recognized. Alternate CG History is a representation of these ambitions. The work is an animation of 3D icons and signifiers that might proliferate in computer graphics if the technology had been invented in this part of the world. Using stereotypical symbols such as lotus flowers and abstracted architectural details of mosques, Gerilya efficiently demonstrates the absence of such cultures in our generalized uses of computer graphics. Greco-Roman sculptures and architectural elements are staples of vaporwave’s vocabulary, and we take them to be the norm when scrolling rapidly past them on social media. Subverting our expectations of digital aesthetics and computer graphics, Alternate CG History is a reminder to question the visual objects we have taken for granted and established as standard, to consider what and who has been left behind.

In contrast to the viral memes and gifs that speak in the US-centric, presumedly global vernacular, Gerilya’s artworks are clearly situated within a Third World imaginary. Through his humorous yet astute depictions of our past, present and future, Gerilya demonstrates the nuances and cultural specificities that are lost in the supposedly universal art history that we are building in the global market of NFTs. He is only at the beginning of developing Third World Futurism as a broad framework, and there is much more work to be done, not only by him but by all of us, collectively. If blockchain truly enables borderless exchanges, including artistic and cultural ones, then it should create opportunities for artists of truly diverse backgrounds and identities—especially those outside of art-world capitals—to find spaces for themselves and their cultures to be valued and preserved.

Clara Che Wei Peh is a curator and writer based in Singapore. She is the founder of NFT Asia, a nonprofit supporting Asian and Asia-based artists.