Emily Edelman & Sasha Stiles

How do algorithms, blockchains, and artificial intelligence expand the possibilities for artists working with text and language?

Games are fun—and sometimes fun can lead to an eye-opening encounter with serious ideas. Trained as a sculptor, Risa Puno took up designing games in order to make installations and experiences that encourage visceral engagement with social commentary and critique. Her art has taken the form of mini-golf courses, arcade games, an escape room, and a tabletop roleplaying game. “Group Hug,” her first solo museum exhibition, opens at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia on March 1. Calum Bowden is one of the organizers of Trust, a workspace in Berlin that incubates various social research initiatives, some of which employ live-action role-playing (LARP) as a methodology. His work is informed by anthropological thinking about embodied knowledge as a form of research. For both Bowden and Puno, play can lead to the kind of gut insights that are hard to achieve through analytical reasoning. The two met over video chat to share their experiences and compare notes. They started by talking about bringing people into games, then shifted to discussing how they define the concepts of “games” and “play” before getting into projects they’ve worked on and the lessons they’ve drawn from them.

RISA PUNO I come from a sculpture background. A lot of the work I make is public art. I often start with a familiar object, like monkey bars or a picnic table, to give people a point of access and lower the barrier to entry. Games are a great way to get people let their guard down and give them an easy way to engage. I’ve made a few playable mini-golf installations and an escape room-inspired immersive artwork. My upcoming solo show involves a multi-person version of Whac-A-Mole.

CALUM BOWDEN I approach games from my studies in anthropology, and what I learned about immersion in various social practices. In terms of game design, I’ve been very inspired by game designer Susan Ploetz—also a co-conspirator of mine—who works in the Nordic LARP tradition, which puts a lot of emphasis on collaborative worldbuilding, using minimal props and scenography. Nordic LARPs usually have a two-part structure. Players familiarize themselves with a game design document ahead of time, but a lot of the details are fleshed out in a workshop before the game starts, whether that’s the identities of characters or the relationships between them or aspects of the world. By keeping rules minimal and inviting people to create a world together, you create something that people feel more comfortable participating in.

PUNO How do you define play? We’re both talking about how to encourage active involvement, but I realized we might not be answering the same question.

BOWDEN I borrow a definition from the anthropologist David Graeber, who talks about play as almost this divine, impossible, utopian thing. Whereas games have rules that can be discerned and written down, play has no rules. Play is potentially dangerous because it’s ungovernable. Rules and games may be generated through play, but ultimately I don’t think games construct play. I don’t know if that answers your question, but I like the idea of play as something almost unattainable—that as humans we’re always being governed by some spoken or unspoken rules. What do you think?

PUNO When I think about play I think about freedom from the norms that govern everyday life. I don’t think of games and play as the same, because there’s free play. I’ve been reading a book called Repairing Play: A Black Phenomenology (2023) by Aaron Trammell, which says that limiting the definition of play to that of something pleasurable “holds bias toward people with access to the conditions of leisure.” There was a game that enslaved children used to play called Hide the Switch, where one took on the role of the slave master, and the other players would run away. European theories of play don’t really have a way to describe that, but it was a game, it was play. I’m interested in how play can be used to explore topics that might be difficult or even painful to discuss under “regular” circumstances. I feel like I’ve only started learning about what people do in LARP, and I’m really interested in that because it really pushes beyond other forms of game design.

BOWDEN There’s a delicate balance of game-making in general: how do you create something that’s generative, that people are able to contribute to, without putting the pressure on them to make something up entirely on their own? There are a lot of different methods and approaches. Coming with some narrative elements—like characters, roles, and preset events—provides components that players can combine in different ways. Are most of the games that you do sculptural? Is the physical dimension of play important to you?

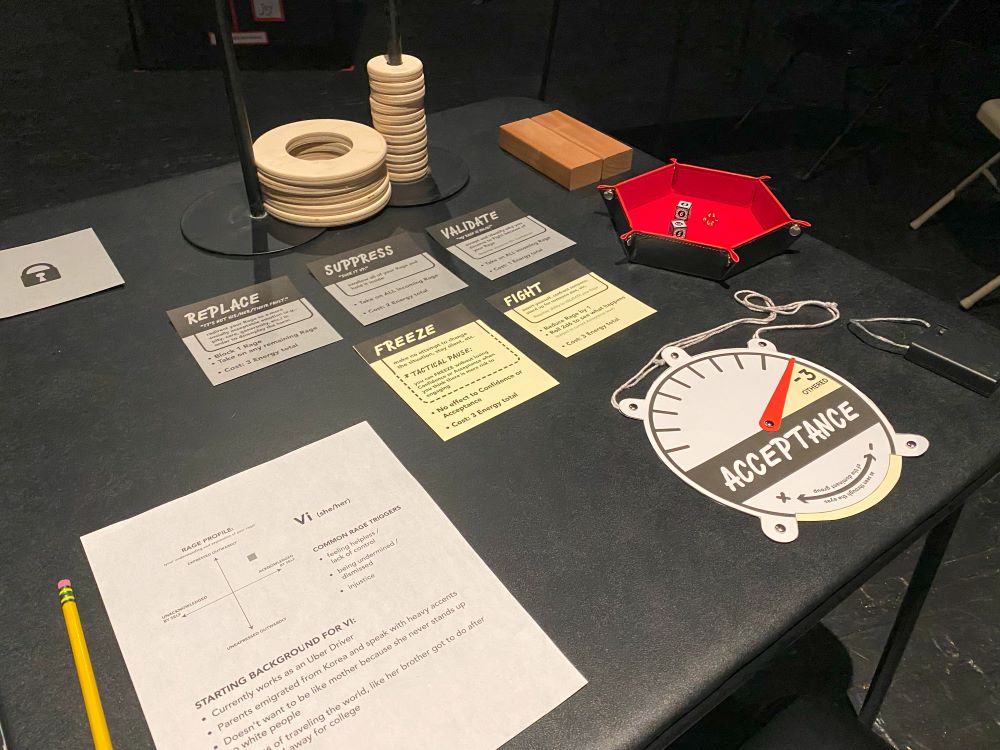

PUNO Historically yes, though I am branching out. Recently I was in SoHo Repertory Theater’s Writer/Director Lab, where I collaborated with Ran Xia on a project called Unresolved Rage Game (2023). It’s a tabletop role-playing game—or rather, it’s an immersive experience based on a TTRPG that we wrote about Asian femme rage. We took it to “Worlds in Play” at Arizona State University’s Mix Center in January. A lot of it is theater of the mind, but it’s still a physical experience. There are props because I think in terms of sculpture. I couldn’t help myself! I didn’t want to make character sheets because for me it’s much more fun to represent stats with physical blocks. It makes it easier for everyone to track the group’s resources, plus it gives literal weight to the consequences of your decisions. I like using objects, as well as space—thinking about physical proximity, for example, as a metaphor for emotional closeness or social closeness.

Ran and I had both played Dungeons & Dragons, because that’s what most people play when they play TTRPGs. We’re not really into the part of D&D where you go to a place and kill everyone there and take their crap, but we like the collective storytelling part, and we were interested in using that as a medium. There’s also something about the complexity of rules in TTRPGs and the resulting gatekeeping effect that seemed like an interesting way to represent the confines of an oppressive system. In Unresolved Rage Game, we lean into that. It’s designed as a tool for Asian femmes to unpack and access and express different relationships with rage. Each character has a different rage profile based on whether or not she acknowledges her rage internally and whether or not she expresses it externally. Instead of medieval monsters you are dealing with modern microaggressions. You have stats like Confidence, Acceptance by the Dominant Group, Energy, and of course the incoming degrees of Rage. Like many of the things I make, it’s weirdly fun, but also uncomfortable and super cringe-worthy but hopefully cathartic in a way. What are your LARPs like?

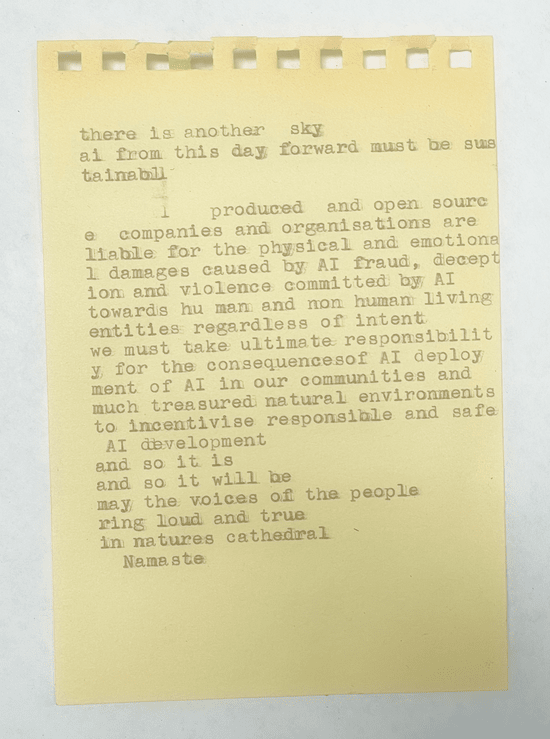

BOWDEN A recent one I devised was called The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (2023), which was inspired by the paperclip maximizer, the thought experiment about a superintelligent AI given the task to manufacture as many paperclips as possible but not programmed to be aligned with human values, and so it turns everything—even humans—into paperclips or makers of paperclips. AI companies have been stoking this mythic, Promethean fear of a great technology we birthed that will eventually kill us all. So I was curious about making a game that would allow players to situate themselves in different perspectives around this issue.

It’s set in a fictional world called Neopia, with groups of players acting as a small AI company, an online community, and a superintelligence. It was pretty fascinating, because it basically reflected the way humans project their worst tendencies and their fears onto technology. It was the players with human roles who were creating intense competition and fighting for resources. In the end, the superintelligence didn’t play any role in making this game violent. It echoed what you said earlier about games being sandboxes for negative feelings, for better or for worse.

PUNO That is fascinating. First of all, I totally want to play that game. And secondly, I find it interesting that many people are worried about robots taking over the world. Maybe I’m naive but I am way more worried about people using robots to take over the world. I feel like your game proves that.

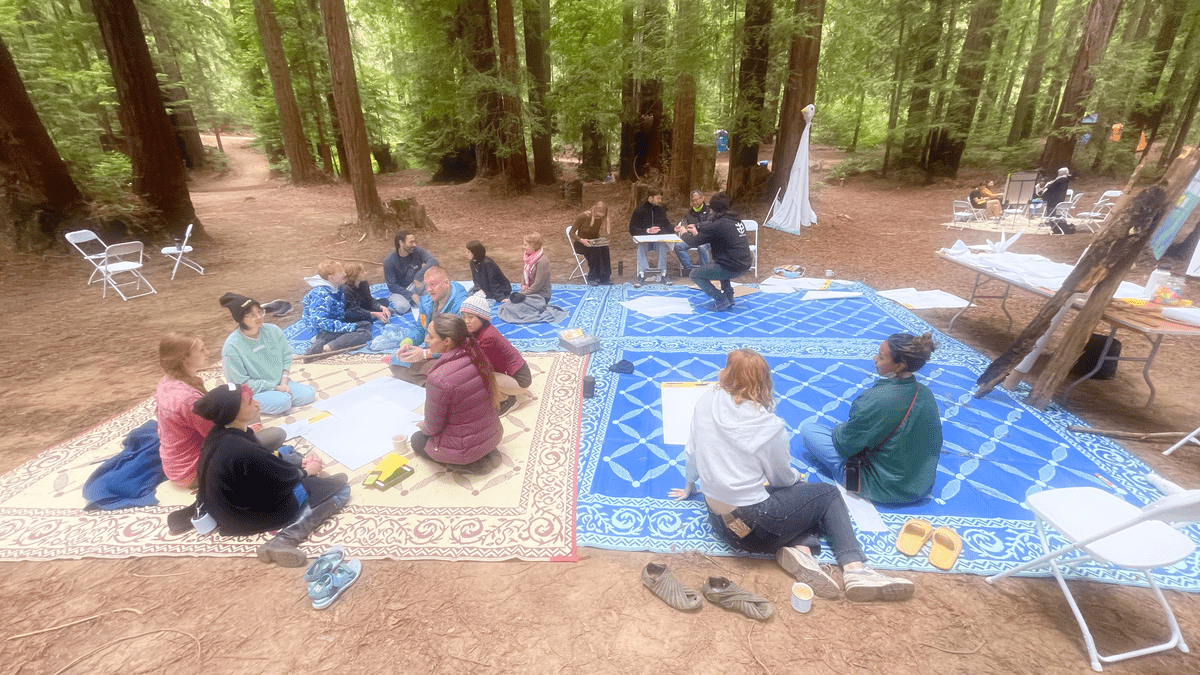

BOWDEN Yeah. Neopia, the name of the world, is an anagram of OpenAI. So it was definitely inspired by this ongoing discussion about AI alignment. The first time I played it was at DWeb Camp, a conference about open-source software and the decentralized internet that takes place in the forest of Northern California. I don’t think I attracted any AI people. It was mostly artists and blockchain people. I thought it was kind of ironic that none of the AI people wanted to explore different perspectives within this ongoing discussion that they’re having, but maybe they’re already too sedimented in their ways of thinking. But I think in general trying to find ways to create possibilities around ongoing debates or discussions, especially around how technology is governed or how people give value to things, is really interesting and exciting.

PUNO Yes. When making a game about difficult topics, you have to ask yourself: Is the goal to make a game about the world as it is or the world as I think it should be? Personally, I almost always go with the world as it is, and describe the shitty thing that I see happening. The Privilege of Escape (2019) was an escape room that modeled social privilege and systemic inequity—participants were divided into two groups and given identical exercises, except one group’s room had full-spectrum light and the other only had red light, which made it impossible to discern the colors in the room and therefore much harder to complete the exercises. Most Likely to Succeed (2021) was about fairness in AI, because a computer uses a webcam assessment to predict your success at playing a dexterity-based maze game, then assigns more time to the people it determines are more skilled. Unresolved Rage Game is built on a system that is meant to feel limiting and oppressive. The tricky part of making games about difficult topics is figuring out how to do it in a way where you’re not re-traumatizing people.

When designing The Privilege of Escape, I thought about whether systemic change should be possible in the game. I made a whole flow chart. If systemic change is allowed in the game, would it be mandatory or optional? And if it’s optional, would the players have to work for it, or sacrifice something for it? If they have to sacrifice something, what do they value enough in an escape room for it to feel like a sacrifice? To incorporate this possibility, I redrew the floor plan, redrew the puzzle flow, rewrote the script, and then I took it to our social justice consultants. They said, “Cool, except this kind of feels like white savior behavior.” They were right. So I had to nix that completely. I was open to creating something hopeful, but I didn’t want to make a tidy solution that makes someone feel like privilege is something you can solve or escape. So it’s about figuring out what things you want to include and what things you don’t. Even if the game is set in a fantasy world, you’re still dealing with power dynamics. There can still be themes of colonization and oppression. What behaviors are you punishing?

BOWDEN When you’re creating role-playing games, there are multiple types of translation between the world we live in and the new world in the game. When I made The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, I was interested in the AI alignment problem. I was grounding it in current events. But each player brings their own values, their own experiences, their own traumas. You brought up the importance of safety mechanisms—this is such a key thing to be thinking about. If you’re making a role-playing game, you’re creating this coalescence of so many different realities that people are living. So how do you make sure it doesn’t descend into some kind of traumatic prisoners’ dilemma–type scenario?

Usually I make a game in service of something else. My work often tests various coordination challenges like decision-making mechanisms. I’m interested in how it feels to embody different perspectives related to the governance of technology. My games are part of a research initiative that wants to value and foreground embodied knowledge and experience, and think about not only what we can learn when we design a system but also what we can learn when we enter a particular perspective within that system. Games are a really interesting way to combine the systemic with the embodied.

PUNO I think the various perspectives, especially relative to the system, came out most in my work through the distribution of fictional resources in The Privilege of Escape. The people who were assigned to the room with full-spectrum light almost always got out first, and they got candy. In our game, candy was the metaphor for economic privilege, while light signified social privilege. When people learned they had that privilege they felt guilty, and the people who went through the red-light room would say, “Well, you didn’t share your candy.” So that became a metaphor for reparations. The resources are fictional, but they become something people discuss in the game.

BOWDEN The origins of contemporary RPGs can be traced back to war games, which are usually zero-sum games. Somebody’s loss is somebody else’s gain, and the game mechanics embed these very particular sociopolitical affordances. A zero-sum game creates violence—you can only win through the destruction of your opponents. So I think it’s important to think about how we can create positive-sum games, or games that don’t have clear winning conditions. I try not to put explicit winning conditions in a game. I think it’s interesting to see how people create them.

PUNO I was listening to a podcast about Nordic LARP where they talked about playing to lose. That’s something I’ve been thinking about as I’ve been playing more TTRPGs for research. I’ve been really appreciating systems other than D&D, which really pushes you to optimize your character’s stats. I’m into systems that instead encourage you to take risks that move the storytelling forward. The Avatar: The Last Airbender TTRPG system is a good example. I’ve never seen the cartoon or read the comics, but the balance mechanic is beautiful. I’ve also played the Alien TTRPG system. Both game systems make it so that you’re willing to take decisions that are disadvantageous for your character but make the story more fun for everyone. It’s less about a win or lose condition for the individual player than about the collective win of having a good story.

Do you think games have to be fun? You said you don’t make games to make games—you make games to get to something else. And I feel the same way. But when I think about things that are made to be fun, I think about entertainment. So why do you make games and not something else to explore the ideas you’re interested in? I think of games as challenges that people willingly take on—that’s one of the reasons why I like them.

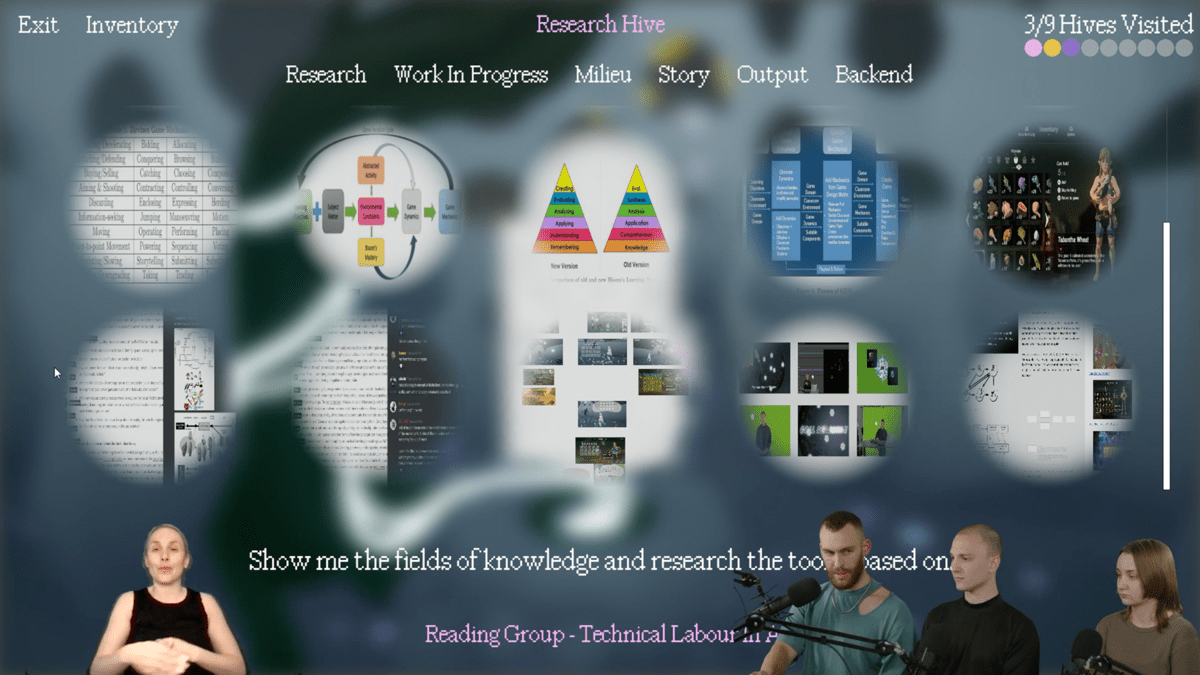

BOWDEN I think games are uniquely positioned to explore complex systems and to think about the world as a multiplicity of truths and experiences and perspectives. It’s quite interesting to lead people through the process of creating a game. The collective project that I’m involved in, called Trust, has tried over the years to think about what constitutes knowledge, and how a game can be a form of research or knowledge production. One game that we made was called Hivemind (2022), which is basically a trivia game set inside a maze that we designed to be used by artists and anybody who has created a system, so they can explore the inner workings of their process. The players are asked a bunch of different questions and have to respond by finding research artifacts in their inventory. This game was based on a concept called the operational chain, which is a methodology for breaking down different types of knowledge that go into any kind of archeological production. We tried to transpose that systemic framework onto this playful maze game.

PUNO I love that. First of all, I want to play that too, but I also think it’s weird that I’d pose the question of why you make games, because my initial reaction is: Of course you’d turn that into a maze game. It seems like the ideal format! But I’m going to ask you the questions that people always ask me—why make a maze game and not something like, I don’t know, a flowchart or something else much less fun? Why turn it into something absolutely delightful like a maze game?

BOWDEN I had too much fun doing Model UN in high school. I think that serious things can be playful and should be playful. I’d rather find my path through a maze than make a flowchart, but maybe you can make a flowchart while you navigate a maze as you decide what’s important to you.

PUNO I’m 100 percent with you. It’s fun. It’s also more memorable. when you experience something with adrenaline. It fires up your limbic system, which connects emotions to memories. So you’re more likely to remember something if you experience it as a game rather than as a flowchart. Attending a seminar about social privilege is very different than having the embodied experience of sitting there and watching people and feeling really super smug about your performance, and then feeling like an asshole when you realize they had it a lot harder than you did, and maybe you shouldn’t feel so smug. What convinced you that the other person’s failure wasn’t their fault? How are these feelings depleting your energy? We do this reflexively, but breaking it down into game mechanics creates a different level of accountability within the safety of the game. That can still be weirdly fun.

BOWDEN I’m curious—what context your games have been situated in? Is it usually an art context?

PUNO It’s usually within an institutional context, so people think they’re going to an art experience that ends up being a game. But in some cases it’s more spontaneous, like my project for the New York Department of Transportation’s Summer Streets program. People might be out riding their bike and then run into my nine-hole mini golf course, The Course of Emotions (2008), where each hole presents an emotional obstacle to overcome.

BOWDEN That sounds really fun. I believe we do live in a ludic age, which can mean our lives are affected by economic policies based on concepts from game theory. Echoing the Graeber idea I mentioned at the beginning, bureaucracies have complex sets of rules to prevent the danger of play. These bureaucratic systems that we live in are designed to be game-like, to have incentives and give us the feeling of reward. Maybe playing games offers a way of better understanding the games that we already live in, while also creating possibilities and ways out.

PUNO Everything you say makes a lot of sense. So much now is being gamified. I’d even say that games are being weaponized and exploited in many ways. Play is being used as a way to get people to produce more on campuses of big tech companies. I do think that it’s important for artists and game designers to hold on to play. But I’d be lying if I said that’s why I make games. I make games because I love them, and they’re the language I can use most easily to connect with people. I mentioned the Whac-A-Mole project for my upcoming solo show with the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. I hate Whac-A-Mole and I’m really bad at it. I wanted to create an experience that embodies an anxiety-ridden crisis situation, and to me Whac-A-Mole does that. Games are just the language I speak. I’m really grateful that it feels relevant now, and that other people are willing to listen.

—Moderated by Brian Droitcour