Brian L. Frye & Primavera de Filippi

Do NFTs make copyright obsolete? A debate between two legal scholars and artists.

How can the traditionally empirical fields of science and technology be reimagined to reflect a more mysterious—even magical—reality? Might quantum physics and computing, areas of study replete with unexplained phenomena and paradoxes, offer a useful framework? Libby Heaney is a quantum physicist turned artist who works with concepts and tools from her former area of professional research to explore new ways of seeing and experiencing the world. Since 2019 this has involved the use of actual quantum computing systems to process digital images, whether of Heaney’s own paintings or other visual sources, alongside other technologies and mediums such as AI and blockchain. The resulting works appear in a range of forms, from interactive digital installations to live performances. Sarah Shin’s interest in science, technology, and expanding consciousness similarly has found a number of channels. As the co-founder of the publishing house Ignota, she has published and edited books including Pauline Oliveros’s Quantum Listening (2022) and Air Age Blueprint (2023), written by K Allado-McDowell in collaboration with GPT-3. In a conversation organized by Outland, Heaney and Shin discussed their different pathways to art and writing, and explored how ideas and metaphors of quantum computing not only explain the universe but also offer a form of healing.

LIBBY HEANEY I would have studied art at eighteen, but because I come from a working-class family, they advised me to do something they called “serious” instead. I ended up doing physics as an undergraduate and I was enchanted by quantum physics because it was so fucking weird and magical—just beyond what we experience with our senses every day. I’m not an experimental physicist. I didn’t do any work in the lab because I’d probably break everything. I approached it through mathematics, which gets into the nitty-gritty of strange concepts. I went really deep. I completed a PhD and five years of postdoc. I published something like twenty papers on quantum entanglement.

Entanglement is when two or more entities, even if they’re really far apart, lose their own individuality and dissolve together. Einstein called it “spooky action at a distance.” Since the 1990s there has been huge interest in quantum entanglement as an applied resource for building powerful quantum computers. That was my expertise, but it started to get really dry. It lost its magic. But I was always making art—painting and drawing. I’d saved up some money, so I went to Central Saint Martins and did an MA. That was ten years ago.

SARAH SHIN It’s interesting to hear you talk about what your family thought was appropriate. As the child of Asian immigrants, I had a similar situation. I was interested in healing modalities from a very young age. I didn’t necessarily understand why. I wanted to study medicine and my family encouraged this. But at the very last minute, I realized that medicine wouldn’t give me the answers, or questions, I was looking for. I ended up studying literature. My interests in science and stories and art and spirituality come from a similar impulse, about curiosity and engagement and a belief in an inherently relational universe—a magical perspective. Maybe that’s where the magic got lost for you, in the sense that industrial science disconnects itself.

HEANEY Exactly. Everything is inherently entangled. As opposed to these fragmented, so-called objective modes of knowledge, which I don’t believe exist. It’s interesting that you’re talking about healing. I was always searching for something else. Quantum physics, clubbing, yoga, psychedelics—experiences that could take you out of yourself, into some other realm of being. As you grow older and you become more aware of things, you start to understand the connections that you’ve been making more clearly. I think that quest for understanding who you are was really important for me, and was one of the reasons I moved over to the arts.

Maybe this is a good point to talk about making art with quantum computing. When they’re fully developed, quantum computers will be able to solve scientific problems that couldn’t be solved in a human lifespan by even the biggest digital computer imaginable—things like breaking encryption, simulating new drugs. For now, while quantum computers are still in their infancy, we can use them to create quantum superstition and entanglement, which can in turn be harnessed for quantum computing tasks. Quantum superposition is the ability for an entity to be in two or more states simultaneously: it’s intimately connected to entanglement. Both of these quantum states of matter are really delicate. If the particles interact with anything—with us, with another atom, with a vibration—they deconstruct: they randomly collapse back to being Newtonian. It’s very strange but scientists know this happens. They’ve tested quantum collapse in many different ways in the lab. When making art with quantum entanglement and quantum superposition, and through the process of random collapse, I gradually create nonbinary patterns that would not be possible using any digital computer. I then use the patterns from different ways of looking at quantum entanglement to animate or create compositions generatively, and you start to see a world that is in flux. Objects can blur together so that you can’t tell them apart. It’s different to layering—it’s a plural way of connecting. It’s hard to describe but it’s great for making art.

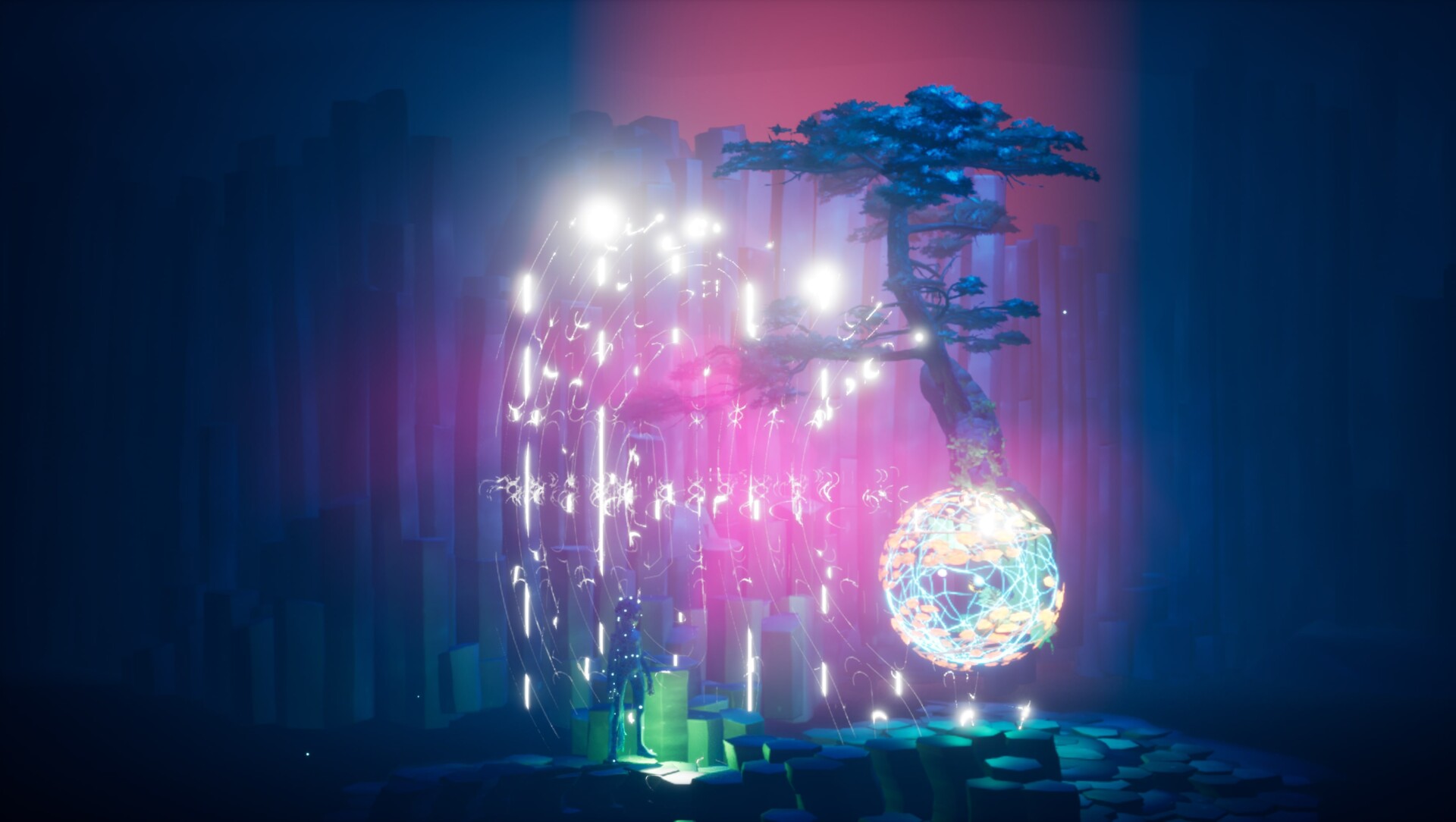

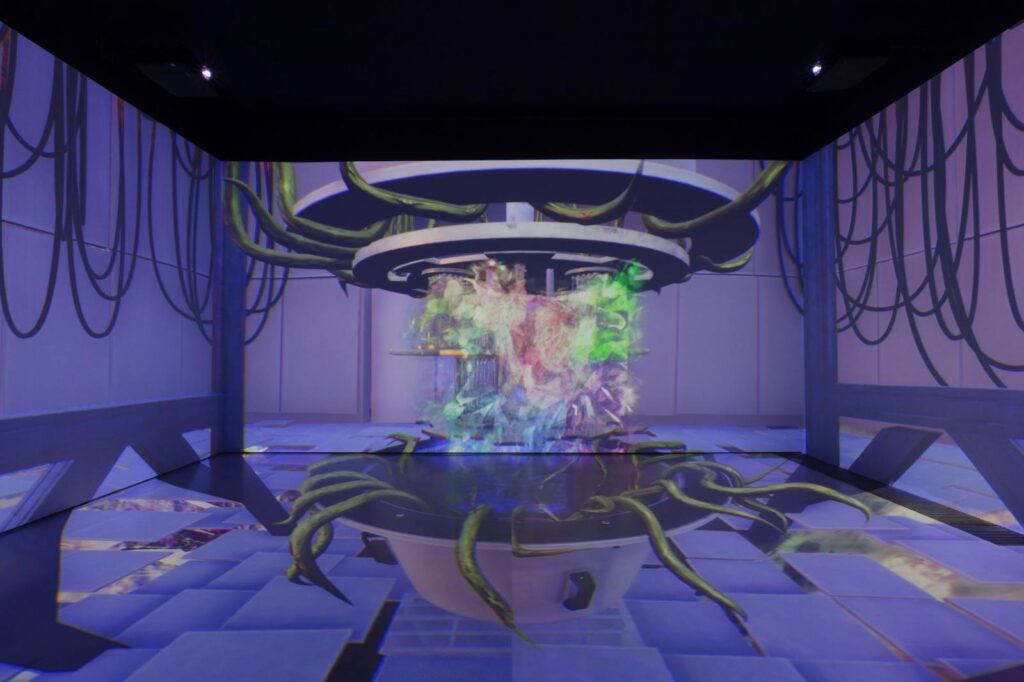

I used quantum computing to make Ent– (2022), an immersive projection commissioned by Light Art Space in Berlin, which I showed there and then at Arebyte in London last year. I animated a series of watercolor paintings of hybrid creatures inspired by Bosch’s medieval monsters using patterns from quantum entanglement and superposition. The work enabled audiences to be moved by quantum vibrations and patterns. They could start to dance with them. I think quantum experiences can help people realize that things aren’t boundaried and fixed. Within the context of the climate crisis, it’s so important to understand that interconnectivity. You can start to see and feel how that looks using quantum computing. But there’s still so much to do. At the moment, it’s myself and a few other practitioners. We’re right at the start of discovering what’s possible with quantum tools.

SHIN Quantum research means that we can get small enough to go underneath the baggage of tradition and culture, to remake their oppressive narratives of reality. The way out is the way in. I’m interested in how quantum theories can shed light on the human psyche. The weirdness of quantum physics at a core level correlates with, and offers a useful dialogue with, how weird certain psychic phenomena are. Jung, for instance, felt that quantum theory could hold insights into precognitive dreams: how does the unconscious perceive things before the conscious mind?

Materialist scientific paradigms have gone far in one direction but quantum is a pathway to embracing what is difficult to account for in a rational way. The origins of some psychological research are in what we would today consider strange subjects for empirical research such as spiritualist seances in the 1890s. It’s important to remember the spirallic shape of culture and science and human activity. Ursula Le Guin suggested that civilization had become too intensely yang and that for any kind of betterment we need to move inward—yinward.

HEANEY I was recently reading Gabor Maté’s book The Myth of Normal (2022), about healing as a process. And I was thinking about trauma as quantum because the past and the future and the now exist in your body at the same time. So, all time is in you in any lived moment, and then the past trauma affects your future, and the shape of your future affects your present. It struck me that both trauma and quantum share this conception of time as collapsing.

I’ve been working on some paintings, collectively titled Five Slimy Orifices, Straddling 32 Dimensions (2023). Last summer I did loads of free drawing because I was trying to quit alcohol for a bit, and I wanted to keep my hands busy. I’m making thirty-two similar but different paintings based on one of these free drawings. Each day I do one or two and they resonate with my emotions that day. I’m trying not to think too much. I’m using watercolor, because of the fluidity of watercolor and the leaking and blurrings of the boundaries. In a way they represent quantum entanglements. But they’re also a self-portrait. I’m trying to let go of meanings and just keep them open because I think open work is very quantum. With technology and art, I’ve found that there’s a tendency to fix things early on rather than play. So I think having this other way of working that is more fluid, both literally and metaphorically, is quite important.

SHIN I think this idea of trauma as quantum shows why quantum metaphors are so helpful because they give another language for existing languages to talk about things which are multiple and sometimes paradoxical. What has been healing for me is the ability to hold things in relation narratively even when they don’t quite make sense together. And this is where I think there’s a limit to my interest in science and scientific language and methodology (even though this paradigm of emotional healing has been shown by neuroscientific research into mirror neurons). But when you are trying to pin something down and prove something it almost loses its functional relation—it severs the relative dimension of it to the rest of life.

My friend Sammy Lee and I are currently making a game about consciousness called Mirror. It has three parts. In part one, “The Sea,” the player encounters the unconscious. It begins with the player awakening within a dream. The player has to develop magical consciousness through a relational worldview, by learning how to read the other-than-human signs in the world of the Sea. The player meets salt languages and doubles and oracles. The game mechanic is essentially reflection and meditation.

The second part, which we’re making at the moment, is called “The Mountain.” This plays out the exchange between the conscious and the unconscious and remembering and forgetting through a memory journey. I worked with this technique to create the installation Memory Garden at the Biennale Gherdëina, in the Dolomites in Italy, last year. The design of the garden comprised a formation of medicinal plants, associated with the different phases of the moon. This time, we are particularly interested in ancient Korean iterations of the memory palace. The landscapes of “The Mountain” sometimes correspond to archetypal fields, which are strongly patterned. When the player enters a field, they play into a web of associations and the patterns of the field act in a continuum with the player’s psyche. There’s also a virtual world called “The Weave,” which contains a Book of Dreams. The final level of “The Sky” will be very quantum in its play with non-locality and spooky action. Throughout Mirror, Sammy and I are bringing together our interests in mysticism and mathematics, mythology and geometry, spirit and matter, altered states of consciousness and diasporic experiences.

HEANEY As you were talking I was writing down keywords like matter, pattern, dreams. And I was like, Wow, she’s building a quantum computer in her game. You’re basing it around the mind but there are parallels between quantum computing and how the mind works.

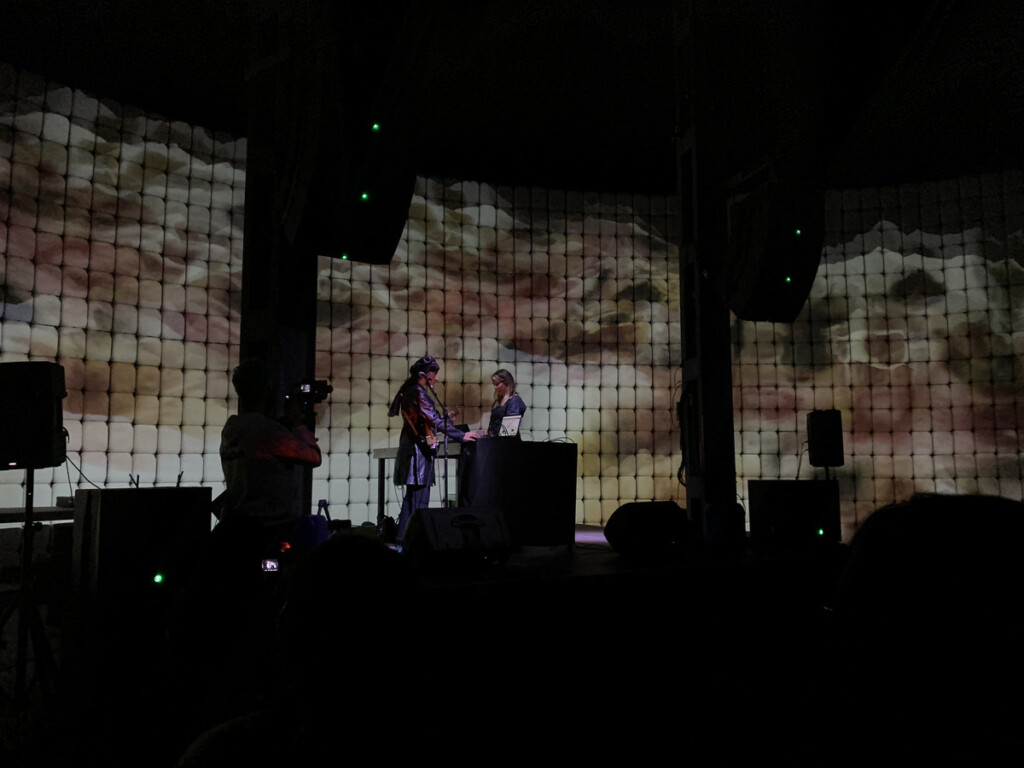

In 2019 I started a project called The Whole Earth Chanting. Nabihah Iqbal and I were commissioned by Loughborough University through Radar, their contemporary arts program. I collected data sets of human and nonhuman chanting from all different sources. This included things like football chanting, Gregorian chanting, Kirtan chanting—experiences where you’re in a collective—but also bird song and the periodic rumblings of inanimate objects. There were rumblings from the quantum physics lab at Imperial College, in London, that were picked up by contact mics. That actually sounded like minimal techno, interestingly. I trained an AI program, WaveGAN, on these sounds, so at certain points different types of chants blurred together in the latent space of the GAN to create hybrid voices that were neither human nor bird or machine. The idea was to subvert the traditional Western approach of taxonomizing. Lots of sub-bass frequencies were pulsating during the performance and you could really feel the music in your body. It felt like the usual categories through which we see the world started to dissolve and new moments of collective identity or belonging with the other, including the other in ourselves, could come into being and then decay.

I’m still working with these machine-learning generated sounds and using quantum entanglement data to weave them together in new, unusual compositions. There’s such a richness to the latent space representation of these sounds that when you go on these journeys into a latent space it is like you’re encountering a series of similar but different parallel universes because of how the AI has reconstructed and arranged these utterances. It’s a paradoxical way of working with machine learning away from the binary. It’s a quantum way of working with it.

SHIN I’m currently rereading Air Age Blueprint by K Allado-McDowell, which I edited last year and was just released. They co-wrote it with GPT-3. There are two characters in this book who are similar, but not identical, to the author. They are fictionalized and GPT-3 wrote memories, affect, and theory from their perspectives. It says things like, “How to stop being miserable and become aware of possible futures” or “How the apocalypse is always occurring here and now.” If GPT-3 is trained on most existing human written language, then it acts as a collective unconscious, with its biases and all. It’s essentially really good at recognizing patterns, right? It must be able to recognize the patterns that are even unconsciously written in by the human author. That it’s able to all this up feels so uncanny.

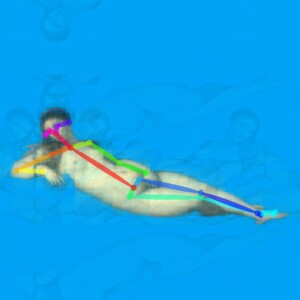

HEANEY It’s amazing, but also there’s the whole issue of machine learning bias. The written word, for instance, has historically tended to come from a lot of white middle-class men. In 2020 I was researching representations of the body in art history. I was looking at bodies which were deemed acceptable by society (i.e., white men) versus those that were seen as ugly or monstrous (usually older women, witches). And then I was looking at AI data sets of the body that are typically used for pose detection. The same bodies that were acceptable in Western art history were in the AI data sets. All the bodies were young, white, fit hero-type bodies or Venus-type bodies. They were no disabled people, no older people, and as far as I know, no trans people. I actually interviewed someone at Microsoft and they tried to justify why this is the case.

So, in 2021 I made touch is response-ability, a touch-screen artwork that can be presented as a performance on Instagram stories as well. In the first frame there’s a digital collage of a Venus figure, but it’s cut out from its background, and it’s being watched by Open Pose algorithm, which is a popular AI pose detection algorithm. The subsequent frames have been processed using a quantum computing algorithm that I wrote to make the body plural and boundaryless, using quantum patterns from entanglement data. Participants move through the frames by touching the images and the body starts to deconstruct or become wavelike or fluid. And as this happens Open Pose can no longer track the body. And then at some point, we can no longer see it either. But it’s still there because as the animation progresses and the frames cycle through, it starts to reappear. It’s just that the digital information of the image went from being binary to quantum (or nonbinary) so it was scattered in a way that was no longer recognizable to humans or to the machine. It’s showing how quantum processes can help us move beyond certain fixed ways of seeing into other fluid ways of seeing.

I’ve bought some books from Ignota over the years. The first one was Ursula Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, where she talks about moving beyond a certain male-dominated hero narrative of technology. But perhaps you can talk about this.

SHIN Yes, thank you for bringing up Le Guin. Instead of heroic stories of winning and action, we can create narratives that are more about things arriving or simply arising. Based on Elizabeth Fisher’s feminist theory of evolution, Le Guin’s argument is that the first human tool was not the spear but the receptacle, or carrier bag—something that holds. My other publisher, Silver Press, is soon publishing Space Crone, which is the first collection of Le Guin’s writing on feminism and gender in one volume, edited by myself and So Mayer.

I was further drawn to quantum metaphors through acquiring and editing Quantum Listening, a reissue of a 1999 essay by Pauline Oliveros, for Ignota. I had the honor of working with her partner IONE and Laurie Anderson on their contributions to the little volume, and with the artist Aura Satz, who created beautiful, resonant illustrations based on her Tuning Fork Spell images. The origins of deep and quantum listening were when Oliveros was teaching in Santa Cruz and a student self-immolated in protest against the Vietnam War. Then, when I was editing this book, Russia invaded Ukraine. In her introduction, IONE writes about how she is listening to the sounds of the war on her TV set, at the same time as the roadworks going on in her own street. What use can listening offer in a time of war, which makes people feel so entirely helpless and useless? Quantum listening is this practice of listening to more than one reality at a time, which somehow makes it more possible to tolerate the fracturedness of reality. It’s about being able to hold paradox: to understand that everything is always both.

—Moderated by Gabrielle Schwarz