Metaverse Not Found

As the metaverse falters, Manny Palou’s open-source body scan turned game anticipates other ways of making bodies virtual.

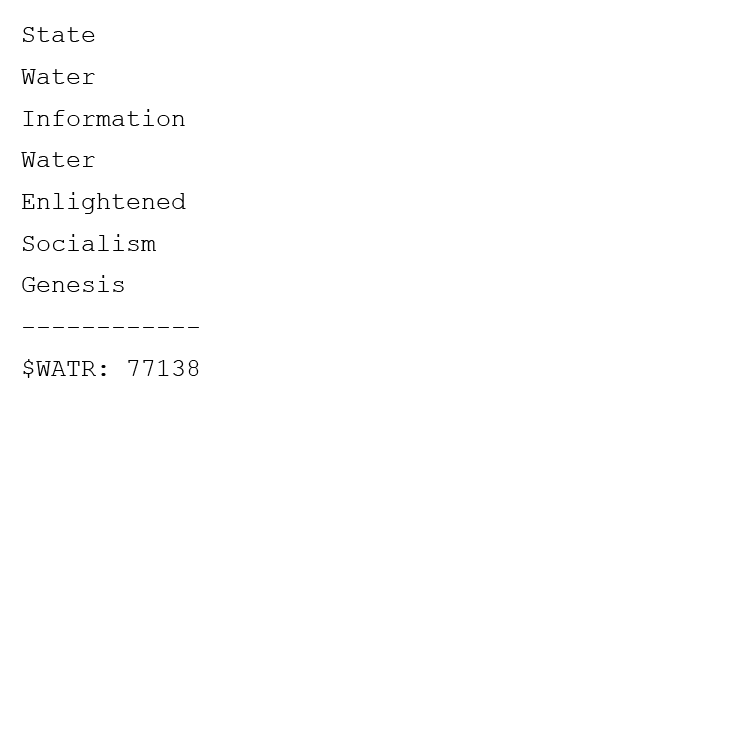

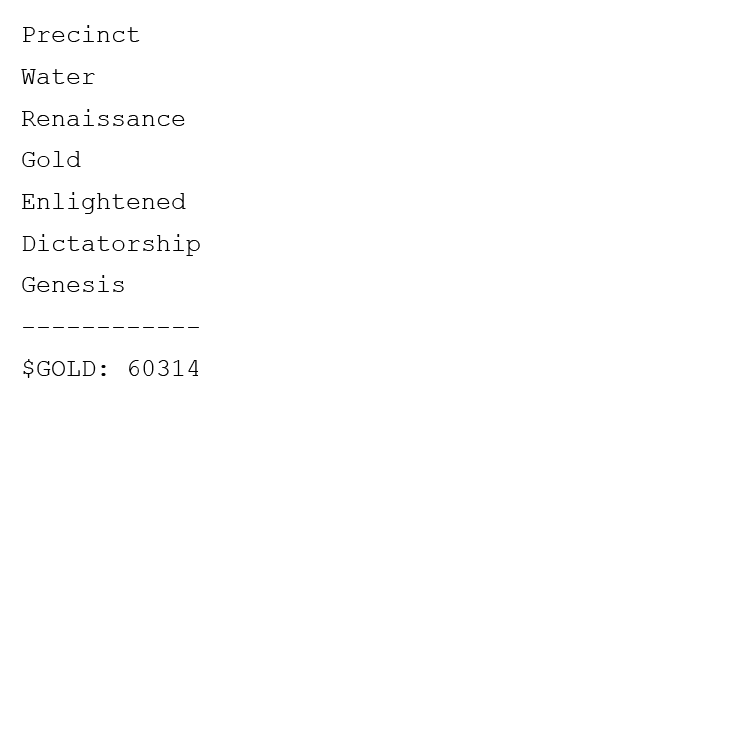

One day in early September, tokens for a game called The Settlements appeared on the NFT marketplace OpenSea. As with many NFT titles, it was unclear just what kind of game it was or how it was supposed to be played. There were no screenshots, FAQs, or tutorial videos accompanying the listed NFTs. The game pieces looked like digital flash cards for a midterm exam about an obscure colonial fantasy world. Plain text listed each imaginary settlement’s size (Camp, Village, Hamlet, Town, Precinct, District); main resource (Wool, Grain, Gold, Iron, Wood); historical period (Renaissance, Classical, Future, Information, Modern, Ancient); government (Dictatorship, Communism, Aristocracy, Oligarchy, Socialism, Democracy); and “realm” (Valhalla, Keskella, Genesis, Shadow, Plains, Ends). A cryptic website for the game suggested these pieces, and the colonial resources they generated, would be used in a “turn-based, on-chain, nft game where rarity can be discovered not determined.”

In its first twenty-four hours, The Settlements generated more than 1,300 transactions—either people paying a network fee to mint a new game piece on the Ethereum blockchain or buying one that someone else had minted and put up for sale. A Discord server bustled, with hundreds of posts from new players eager to see what others were doing. Someone created a standalone wiki to explain the basics—but the gameplay tab was conspicuously blank, as were most other pages. Another person wrote a song about the game, using an on-chain music production tool. As more people joined, the market value of game pieces steadily rose. Nearly ten thousand tokens would be minted, ranging in value from 0.01 ETH (around $39) to 20 ETH (more than $78,000). Like gamblers around a hot craps table at 3AM on an otherwise dead casino floor, there was a hopeful camaraderie that everyone present might profit from some runaway exponential growth, doubling the size of their chip stacks with every roll of the dice while the rest of the world slept. “This is SO AWESOME!” a user called Zhoug wrote on the Discord server. “Look at the $GOLD distribution forming! The players are entering the area. It’s happening.”

The energy poured into the game was out of proportion from the effort that had been put into making it. Ethan Daya, a 24-year-old designer and engineer from Sydney, wrote the code for The Settlements over the course of three days while trying to teach himself Solidity, a common programming language for the Ethereum blockchain. Daya had spent most of his still young career working in marketing and consulting, but in 2020 began working at Zora, a crypto startup dedicated to making it easier to buy and sell digital assets that had raised $8 million in funding as of March 2021. The company’s main technology relied on a cryptographic registry that would let users submit bids for items stored on the blockchain regardless of whether they were for sale or not. Those bids could be stored and tracked over time, giving artists or owners a more accurate valuation of their assets, creating what the company described in a whitepaper as “buy-side liquidity”—basically, a clearer picture of how much real money there was in the market ready to spend. It could also share a percentage of any sale with up to three stakeholders—the original creator, the current owner, and a previous owner—which would theoretically ensure the profits from any sudden appreciation could be distributed to more than just the person lucky enough to own it at the time.

One of Zora’s backers, Vine co-creator turned crypto entrepreneur Dom Hofmann, had created a strange NFT hit this summer with Loot, a pseudo-game that allows players to mint and trade Dungeons & Dragons–style inventory lists. There was no shared game world or quests to use those items in, but for many it was fun enough to imagine one for themselves, and they began coding their own mods onto the blockchain to create 2D maps for worlds they imagined their characters questing in, and simple pixel art to represent the near infinite number of weapons, armor, and artifacts. Daya thought that a similar approach could work with empire-building games like Sid Meier’s Civilization and Age of Empires. He ended up with The Settlements, which he’d thought of as an antidote to the games industry that—as he explained in a launch-day Twitter thread—“began and ended at the gates of these massive game corporations and the items/things we collected weren’t really ours.” Pushing back against the model of games like Fortnite and Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, where massive conglomerates sell players costumes and decorative items, Daya wanted to reorient the games industry around a less centralized vision, where players owned the pieces they played with, and each player’s pieces were unique to them and them alone.

***

Daya’s ideas seemed simple enough when I read them on Twitter, but in November, when I tried to buy my first token for The Settlements, I quickly found myself lost in a multiverse maze of walled gardens, none of which seemed especially eager to connect. I spent a day researching different crypto exchanges to convert my dollars into Ethereum. When I settled on one, I had to pay a 7 USD fee to miners, in the form of “gas,” to convert the 125 USD from my checking account into an absurdly fractional sum of Ethereum. I then created an account with a crypto wallet a friend recommended and installed a plug-in for the wallet on my web browser and moved my small sum of Ethereum into it, paying still another gas fee to complete the transaction.

There was no shared game world or quests to use those items in, but for many it was fun enough to imagine one for themselves.

When I tried to buy my first settlement—the cheapest one available at the time was listed at a price of 0.01 ETH, or roughly 47 USD—I discovered that the wallet my friend had recommended wasn’t supported on OpenSea. After some more research, I found one that was. I created a new account, transferred my Ethereum from my first wallet back to my main crypto account, and then to my new wallet, paying network fees at each step. When I returned to OpenSea ready to buy the settlement I hit another wall when I learned the gas fee to complete the purchase would be around 311 USD, or six times the cost of the token. I briefly considered moving more money from my checking account, but that would have left me short on rent for the next month. After I made peace with defeat and converted my fractional sum of Ethereum back into dollars, I ended up with around 77 USD, almost 50 USD less than I’d had a few hours earlier.

As I tried to figure out what had happened, I began to think that maybe NFT games weren’t meant for people like me. Despite the wave of rhetoric about decentralization and democratization, the world of NFTs seemed even more exclusionary and inaccessible than what preceded them. They reminded me most of high roller rooms in casinos, where it appears as if everyone inside is playing the same game of blackjack as the people crowded around the ten-dollar tables outside. But because high-net-worth gamblers are responsible for such a disproportionate amount of most casino’s profits, many are allowed to customize the rules of each game to their own particular liking. They can choose how many decks are placed in the card shoe, split cards and double down more often than ordinary players, and benefit from rebates guaranteeing that they’ll get back a percentage of their lost money at the end of the night. The game is ultimately a pretext for a struggle over leverage between the high rollers and the casino management. Even if a person like me could scrape together enough money for a minimum bet at a table, I wouldn’t really be playing the same game.

Around the same time that I failed to buy into The Settlements, many early adopters seemed to be questioning their place in the game’s world. Had they been duped into thinking they were buying into a high rollers room, only to follow the winding labyrinth of the casino floor and end up back on the sidewalk? After the flurry of activity and transactions following the game’s launch, things had mostly come to a standstill. The number of weekly transactions on OpenSea plummeted from more than thirteen hundred in the first week to just sixteen in the second, before hitting zero at the end of September. A half-hearted attempt to organize an in-person meet-up for members of the Discord group came to nothing. Daya had stopped posting and no longer seemed to be updating the game’s code. Instead, he posted on Twitter about burnout. “Working 24/7 is dumb and as someone who did it for over a year and a half only leads to not vibes,” he wrote in late November. “Encouraging a culture of pain is not the reason why we wanted to try something different and isn’t going to be the way we convince the world that crypto and web3 is net positive.”

In late November, Twitter user @0xSettler noticed that Daya had removed The Settlements from his bio and gave voice to a thought that many seemed to have been thinking. “man, ethan finally rugged @the_settlements after all,” they posted. “sad day. feels bad man”

“oooooof didn’t think this day would come….” Zhoug wrote from their Twitter account.

“gutted,” 0xSettler replied.

Just two months after the game had appeared, players still posting on Discord admitted they had “come to a crossroads.” Could the community keep working on new ideas for the game without even cursory support from its original developers? Or should they accept their collective losses and move on? Some turned on Daya. One player, GoalieThom, encouraged people to “be careful for any next project that comes from the original dev (and be careful with Zora if this is how they handle projects).”

After several days, Daya finally posted an apology and an explanation, saying he had been overwhelmed with other work at Zora, which had opened markets for more than one hundred other NFT projects like The Settlements. He disputed claims that the game had been a scam, claiming he had lost between 2 and 3 ETH trying to make it work. “Like I said in my first ever tweet this was a child of my 3rd day of solidity (V2 exists because I wrote bad code) and was keen to just try something out & I was so surprised people got involved,” he wrote. He offered to hand over the code he had written for The Settlements to anyone interested in trying to keep the game running, but admitted they would be on their own.

***

In a 1977 interview, Barbara Walters asked Dolly Parton why she wore such outlandish wigs and makeup. Walters seemed to suggest that there was something fraudulent in Parton’s appearance, that it was intended to manipulate her audience into becoming infatuated with a person who wasn’t really there. For Parton the ornamentation was a necessary precondition of stardom. She created her image to make people happy, not to manipulate them. “Show business is a moneymaking joke,” she said. “And I just always liked telling jokes.”

The world of NFTs is often described as a joke, but it’s also a moneymaking one, prone to exponential growth that can often seem as suspiciously unreal as one of Parton’s wigs. The fantasy soccer game Sorare saw quarterly sales grow more than 5,000% year-over-year, with more than 150 million USD in revenue in 2021. The Pokémon-esque game Axie Infinity saw monthly revenue grow from 670,000 USD to 350 million USD between April and August of 2021, while creating an unexpected new career path for hundreds of underemployed people in the Philippines and elsewhere. These gains often come with a veneer of bizarre pixel art, illegible glitch fonts, and in-crowd vernacular so impenetrable it seems like an obvious signpost for a scam. As software engineer Stephen Diehl put it, “Any application that could be done on a blockchain could be better done on a centralized database. Except crime.”

Yet what’s unique about the crypto world is not its susceptibility to fraud. Daily life is already suffused with legal or unprosecuted forms of corruption and deceit—whether it be Facebook inflating its video view numbers to justify higher ad rates, Boeing’s disastrous lies about the 737 Max, Bank of America’s deceptive coercions to bilk struggling homeowners out of a few more payments before foreclosing their homes. No one enters a high rollers room thinking the odds are in their favor. People enter because it reminds them that winning a life-altering jackpot is a real possibility. Even if they spend the night losing, the aura of money and the peripheral sounds of someone else’s lucky streak are enough to stoke the imagination and resupply their determination to keep going for a little while longer. In the same way, the self-evident reality that there is often, or always, no there there with NFTs is part of what gives them power. It creates negative space that can be filled with entrepreneurial optimism, which, like a painted face or an artificial bouffant, can draw attention that becomes its own reason for being.

The self-evident reality that there is often, or always, no there there with NFTs is part of what gives them power.

As the remnants of the community of The Settlements players tried to figure out what to do next, it began to seem as if many had grown attached to the game not for what it was, but because of the chance it gave them to daydream together of a brighter future they were sure was still coming. On Discord, Zhoug tried to organize volunteers to take over, suggesting a potential migration to another blockchain with less onerous network fees. In exchange for their work, volunteers would collect a 30% commission on every future transaction. “Hype can come back quickly,” they wrote, “especially for a resurrected asset (look at CryptoPunks). It could still be an epic game.” Another user suggested adding a feature that would let existing players combine their settlements to create cities. Existing players could also potentially “stake” new users—covering their upfront costs for acquiring a settlement—to try and expand the community. Someone else suggested trying to connect the game with Treasure, another new NFT project with a similarly nebulous fantasy design. One user suggested that Daya could donate any funds generated from minting game pieces to form a treasury to help the community fund the game’s ongoing development, but Daya shot the idea down, saying there was no money to donate.

Soon trolls began posting among the true believers—“ded,” “wen refund,” and other faithless digs—but the diehards laughed it off. While there were still dozens of hurdles in their way to keeping The Settlements going—high gas fees, special programming languages to learn, new game design concepts to prototype—fans were defiant. As long as there were even just a few people keeping the flame alive, they had hope, and that made their cryptic little squares of plain text seem precious. “we’re going to be dead and gone before Settlements is lol, it’s churning away on-chain. L2s are ramping up faster than expected, once us codey-boiz and girlz get up to speed on how to do this shit,” Zhoug wrote, “we’re gonna come back and build.”

Michael Thomsen is a game critic. He is writing a book on mixed martial arts.