The Museum of Crypto Art

Cofounder Colborn Bell shares his vision of democratically governed art institution for the metaverse.

For almost a decade, Transfer has been bringing digital art into exhibition spaces and into collectors’ homes. Founder Kelani Nichole has organized over eighty solo shows, experimenting with new models for presenting time-based media art in the white cube. In addition to supporting artists through exhibition opportunities, Nichole has also built an expansive collection of digital artwork representative of the gallery’s community. Here she reflects on her personal collection—which she considers to belong to Transfer as well—and how it has helped her understand the importance of stewardship and preservation in the digital art space.

Transfer was founded in 2013 in a warehouse in Brooklyn. It came out of early curatorial work that I had been doing with a collective called Little Berlin in Philadelphia. The collective maintained an “undefined exhibition space” open to different types of curatorial interests, and my interest at the time was net art. I had been working online in my career as a UX designer for a decade at that point, and it made sense to start looking at art online as well. An article titled “The Digital Divide” by Claire Bishop came out in Artforum in 2012, and I felt like she had missed what I was seeing in these practices online. My response to that was opening Transfer. In the early days, we only produced solo exhibitions; this allowed us to focus individually on each studio by giving over the space to one artist at a time to really experiment with what it meant to bring their practice away from the screen.

Early on, I realized that my practice at Transfer looked a lot more like philanthropic support of these studios than a traditional gallery-style representation of artists. I saw this effort as a long-term investment in the artists, and I wanted to start collecting to steward these works and maintain that early investment. Most importantly, the reason that I started collecting in 2015 with a purchase of Lorna Mill’s gif Dream Muscle was that I wanted to understand what it meant to have it in my home, to turn it on and off each day, and dwell with the art.

I think artists working online fit in the larger historical trajectory of time-based media art. As a gallerist who has represented websites, and made a market for new ephemeral and distributed formats, I have developed a rigorous process for what it means to acquire a work of time-based media art. NFTs have created an interesting mechanism and value proposition that has caught the attention of popular culture. Now everyone sort of understands what it means to want to own something that everyone else can also see online. I strongly believe that NFTs are really only one possibility for how decentralized technology will transform our relationship not just to art, but to many, many things in our lives and in this world.

When NFTs really took off, I abstained from collecting on Ethereum—that’s not something I’m interested in. Environmental impact aside, it just wasn’t the type of market that I wanted to participate in. When Transfer’s director Wade Wallerstein and I noticed that many of the artists we work with were jumping into Tezos, we followed them and started investing and collecting. Lorna Mills was one of the first Transfer artists to get on Tezos. She was creating atomized pieces from her installation works and releasing them in large editions to make her work accessible. We collected a ton of them, and saw that as an archival activity. Now Transfer has a very prolific collection.

Another artist who’s been in my collection for a very long time—and the first piece that entered the Transfer collection on Tezos—is Faith Holland. I love Faith’s work. It’s a pillar of both Transfer’s program and my collection. Ever since I showed her Ookie Canvases, I’ve had one hanging above my bed. These are very special digital prints on canvas: they’re huge, beautiful physical objects. Her Underwater Internet NFT is a poetic musing about the environmental impact of this technology, and a very beautiful, serene look at our future demise.

I think my program at Transfer is really distinct in the sense that it provides a humanistic look at technology. I often support artists who do more figurative work: you see representation of the body much more in my program, as opposed to digital work that is algorithmic abstraction. For example, Rick Silva, who thinks poetically about humanity’s place in nature in his digital work, or LaTurbo Avedon who is an avatar artist thinking about virtual identity and metaverse spaces.

At one point early on, I noticed that there was a slight imbalance where Transfer had more men than women in the program. That was a wake-up call for me, and I devoted an entire year of solo exhibitions to women and femmes. The work was so powerful in that year that I just kept doing it, and began to incubate this whole movement of feminist artists who were “refiguring technology,” to borrow a term from Morehshin Allahyari.

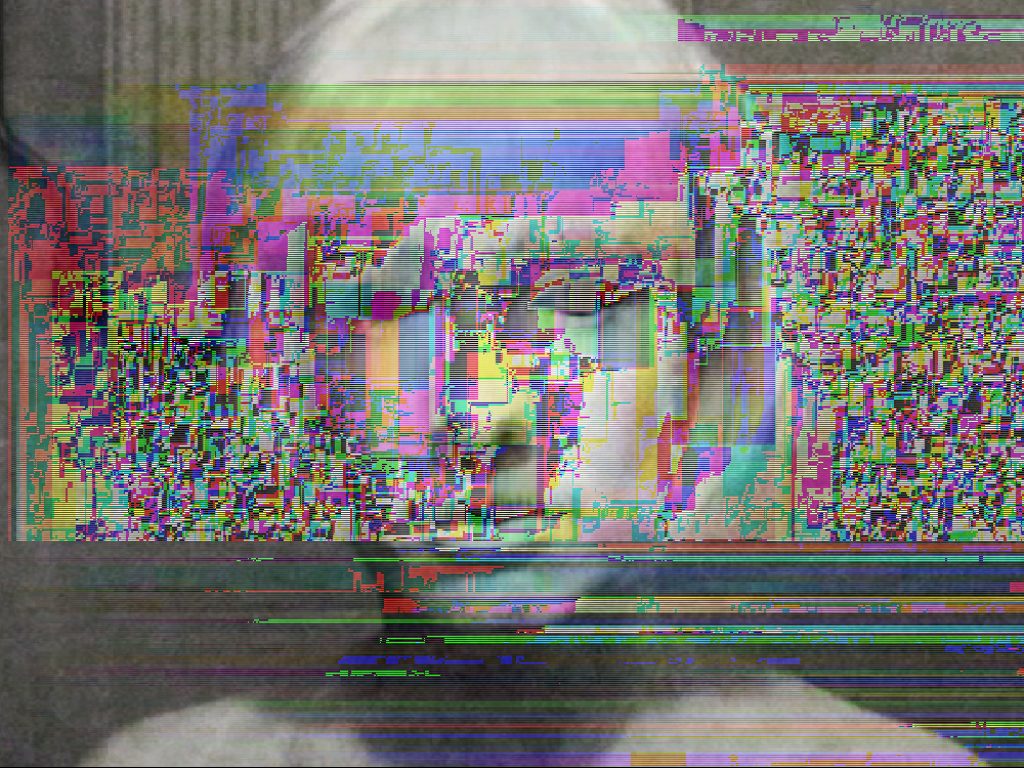

Rosa Menkman is one of many artists who I work with who have a research-based practice. She is one of the founders of the glitch art movement, and published her “Glitch Studies Manifesto” in 2011. It’s always a challenge to think about what it means to monetize, distribute, and exhibit research. She builds worlds, makes video games, and creates environments, but her work also takes the form of prints, publications, and installations. She releases her research for different series on Tezos as PDFs for collection. These include her institutions of Resolution Disputes (2015) and her Glitch Manifesto (2010). These PDFs are already online, but releasing them as NFT editions created a way for collectors to show their support for Rosa and her practice. I also collected Rosa’s A Vernacular of File Formats, which is a print series that she’s well known for. They’re small and portable, so many collectors have brought them into their homes.

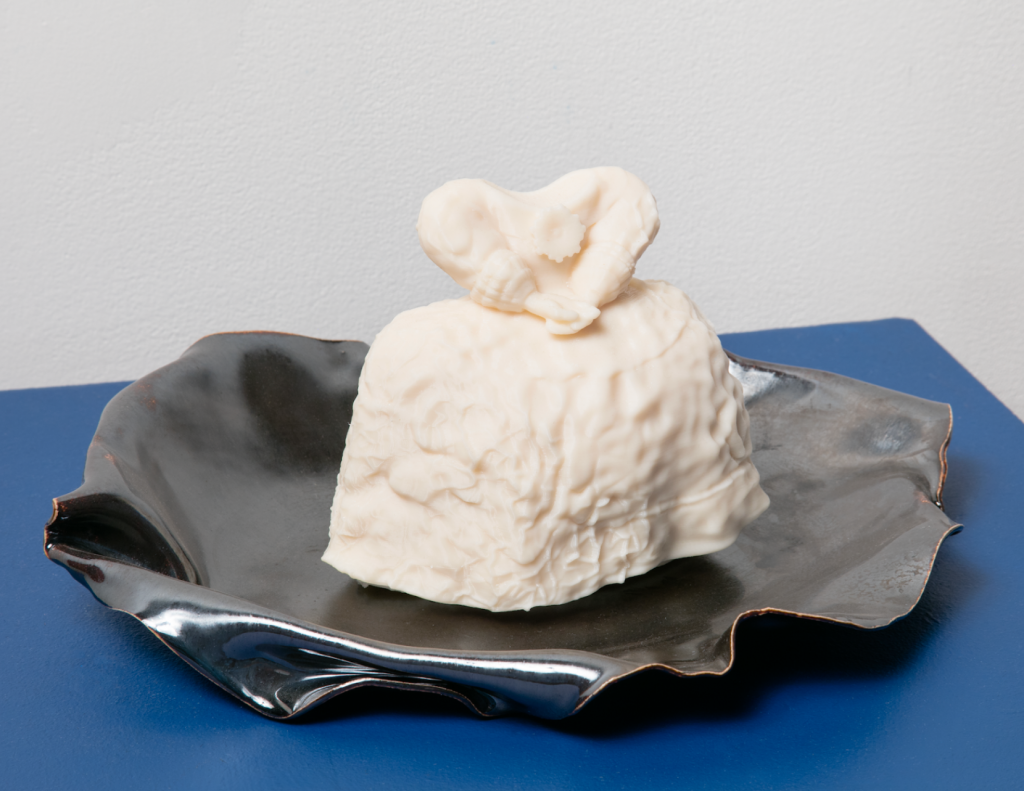

I love the idea of 3D printing as a sculptural medium. There’s so many interesting questions around conservation and ownership with objects like that, that are natively a virtual object—a 3D model. Doll’s House: Tiny Princess Dress, Plated by Claudia Hart references the princess dresses in Velázquez’s Las Meninas as a symbol of a fallen empire, and the physical tactility of the work really brings that idea to life. Hart applied 3D-scanned aged skin to the surface of the dress, collapsing time, representation, femininity, while also questioning surface and virtuality. The 3D-printed plastic gives the object a solid, substantial feeling, and the references to the body—actually, a corpse—become a bit uncanny. Having the object in my home is impactful because it’s a reminder of what it means to work in this liminal space between physical and virtual.

Conservation became central to my practice starting in 2016. The gallery matured and had started to work with bigger collections. When we did our first acquisition with the Whitney Museum, we went through an extensive artist questionnaire provided by the museum’s conservators, and I realized how important and rich time-based media conservation is. Now I see it as my responsibility to try and do that kind of diligence at the time of acquisition, instead of after the fact. It’s important for collectors to invest in the full conservation treatment because it helps ensure the longevity of your work, and their ability to maintain it. Stewardship and conservation are not easy work, and they can’t be scaled. It takes a personal commitment from a collector as well as a specialized individual—a conservator—to sit with the artist and discuss their authoring software, their process, their PC environment, and their files, which are all really important to time-based media artwork.

With Transfer’s most recent online exhibition, “Pieces of Me,” we are trying to set a model for how to bring conservation and stewardship into the NFT ecosystem. For this exhibition, produced in partnership with left.gallery, we’re doing the conservation before we mint the works. So before the works can even be sold, we’re working one-on-one with each of our artists to structure the contracts to reflect their intent for the work, and to make sure that the terms are included within the ERC-721 metadata field. We’re trying to place these works in a way that supports the longevity of the work, as opposed to just treating the work as an easily tradable commodity that you don’t have that relationship to. The gallery has committed to maintaining the works and the website for five years. I hand-coded everything, and didn’t want to put anything into grids or boxes—each work opens in its own tab, and takes over the full screen. We did one-on-one visits with each artist to make sure their work was installed with intent.

A lot of the NFT market is built on the backs of artists, who are also in the most precarious financial situation. They’ve been asked to contribute minting costs to get platforms like Foundation or SuperRare off the ground. With “Pieces of Me,” it was important for us to cover these costs, and provide specialist resources like conservation. Another thing we chose to do is redistribute the proceeds, which is something that should be done at this moment early in the development of decentralized technology if we want to see real change. The artist gets 70 percent of the proceeds when their work sells, and the other 30 percent goes into a pool which is then split across all of the artists and knowledge workers supporting the exhibition. This is a proposition that isn’t about money in a space where everything else is, and emphasizes the fact that this is an experiment with a solidarity economy. We don’t have to give our proceeds over to platforms and whales, and we can instead actually come together and think about building wealth and mitigating risk for artists in this moment of great change.

–As told to Lauren Studebaker