J1mmy.eth

A visionary leader in the NFT space talks about his latest initiative and his favorite digital artists.

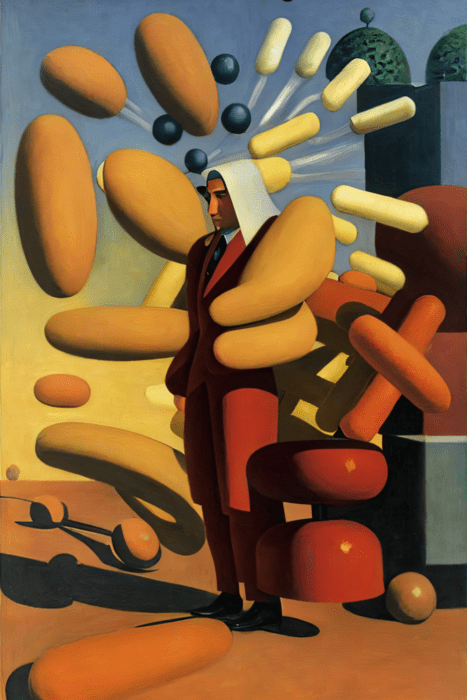

Over the last three years, the art production DAO Bright Moments has honed the proposition that the revelation of the output of a generative artwork is a special occasion that artists and their audiences can share. They have organized projects, events, and exhibitions around the world to highlight and celebrate these moments of discovery. What began at a casual gallery on the boardwalk in Venice Beach, California, will conclude this weekend in Venice, Italy, when Bright Moments presents “The Finale” at the Scuola Grande San Giovanni: a live minting experience that includes almost every artist who has participated in the DAO’s past projects. To mark the occasion, founder Seth Goldstein met with Outland to talk about the evolution of Bright Moments, from the introduction of on-site minting as a practical way to onboard people to collecting NFTs to its positioning of generative art as a kind of participatory performance. The conversation highlights the DAO’s major projects, though its activity extended even further, encompassing residencies, traveling solo projects by Casey Reas and Michael Kozlowski (aka mpkoz), and meetups with smaller-scale presentations of artworks in New York and Venice Beach. As a collector, Goldstein “buys his own supply,” as he puts it; this text is illustrated with works in his vault from Bright Moments events, as well as CryptoCitizens, a pixel art collection with 1,000 NFTs minted for each of the cities where the DAO has been active.

At the end of 2020, my partner Kristi and I moved to Venice Beach from San Francisco. It was deep in the pandemic and we didn’t really know anybody. Around that time the latest wave of NFTs was emerging on SuperRare, Foundation, and other platforms. I think it was stirred up by Covid behavior—people were at home collecting things, whether that was meme stocks or NBA Top Shots or watches. I was taking photographs of sunsets in Venice Beach, and turning them into AI videos using Runway and some other GAN models. I put the videos on Foundation and had my first experience selling a piece of digital art. It was transformative for me. I didn’t have to frame a photograph and ship it across the world. I could just wake up the next morning with ETH in my account and the artwork in somebody’s wallet. As an entrepreneur, I was really excited to think about all the ways that this could unlock a certain kind of creativity.

I grew up as a theater kid and was influenced by the avant-garde scene of the 1970s and ’80s. I was Robert Wilson’s archivist when I came out of college. In 1993 I went to Karlsruhe when they were just starting the Center for Art and Media under Jeffrey Shaw. I worked in the multimedia lab. But when the commercial web opened up in 1995 after the launch of Netscape, I realized that digital art would be tricky to do as a business. So I shifted into internet technology startups, starting with online advertising. And that was my career for 25 years, before I started Bright Moments.

We got a six-month lease on a gallery in Venice Beach starting April 1, and showed NFTs. People would stop in from the boardwalk to watch an NBA Top Shot. The first artist we reached out to exhibit was Jeff Davis, who also happened to be the chief creative officer and one of the founding partners of Art Blocks. We were concerned that when the show opened we wouldn’t have enough people with active wallets to purchase Jeff’s work. So we had the idea of giving away a set of CryptoVenetians, which were obviously inspired by CryptoPunks and other collectibles. The difference here was that you could only get one if you showed up at the gallery. And then we’d help you open an Ethereum wallet on Metamask, and transfer 10 BRT tokens, our native ERC-20 token for the Bright Moments DAO. These weren’t traded on Uniswap. There was no liquidity pool. That’s how we geofenced the experience.

It took time to mint each CryptoVenetian. It was a weird farm-to-table experience at a time when things were happening fast online. CryptoPunks got claimed in a week in 2017, and Bored Apes sold out in twelve hours. These drops were happening so quickly because they were purely transactional. What we stumbled onto is the special experience of a human being looking at a screen with other humans as a work of generative art is revealed for the first time. It’s memorable because you’re bringing something that is mathematically random into the real world.

That live-minting experience has been the most interesting throughline of Bright Moments. It evolved from a fun, degenerate thing we came up with in the summer of 2021 to something elevated, a kind of performance art. Aaron Penne and Boreta had been to the gallery that first summer, and that September we did a project with them called Rituals, which went on to win the Lumen Prize. It’s a beautiful work of 1,000 outputs, 800 of which were minted online—but the first 200 were minted in the gallery over the course of 50 hours, starting Friday at sunset and going nonstop until Sunday at sunset. Collectors had a fully immersive experience; they’d sit in a chamber and write down a few words on a piece of paper, which they’d hold onto as the work was presented to them. It was pretty out there—beautiful, experimental.

Tyler Hobbs came to Rituals, and we started talking about doing something later that year at 150 Wooster Street in New York. People obsess about the traits and rarities in Tyler’s Fidenza (2021). He conceived Incomplete Control (2021) as a smaller collection without traits or rarities. We released it over four nights in December, minting twenty-five works each night. Collectors would go downstairs to a private space, show their mint pass, and the token would be transferred. Security and privacy were important, because a number of people wanted to remain anonymous. Tyler was standing at a giant 100-inch monitor upstairs. As the works were minted, they’d appear on the screen, and Tyler would describe what he saw. Makaya McCraven and Carlos Niño, two of Tyler’s favorite jazz musicians, would improvise in response to the art. It felt like a 1950s beatnik evening with jazz and spoken word poetry. It was thrilling for collectors to be there in that moment, when the artist was seeing the work for the first time. It’s so different from the traditional gallery, where you go see paintings that have been finished for months. And it was an important project for Bright Moments, because we were across the street from where Paula Cooper had her first gallery. It was our entry into a more serious art world.

Randomness is the magic of on-chain generative art. You’re triggering it as the collector. The algorithm is going to give birth to something that is unknowable until it’s minted. In 2022 we did a solo show with Ben Kovach, “100 Print,” that was very different from our other events because he wanted to mint the outputs in advance. We introduced a draft pick: the first mint pass is the most expensive, the hundredth is the cheapest, and the cost decreases as the count goes up. Collectors studied the outputs before the event. I had the fifth pick, and I was petrified of missing something good if I didn’t do my homework. It created this interesting competitive tension, and everyone got really engaged with the algorithm and the outputs.

After Incomplete Control we sold golden tokens and used the proceeds to rent Kraftwerk in Berlin for ten nights in April 2022. Each evening we dropped a new project, and the artist got to take over all the screens in the venue. A few months later we went to London and featured seven artists, each of whom got to have an exhibition for five days at a gallery in Soho. Before Emily Xie’s show, we sat down with her and talked about her algorithm. People had some context, an understanding of her process, when they went to mint the work.

We decided to build on that in Mexico City that November. We had an amazing lineup—Iskra Velitchkova, Marcelo Soria-Rodríguez, Snowfro, Pixelfool, Anna Lucia, and more. And we reached out to Casey Reas to coordinate an educational track. He did a conditional drawing workshop with Zach Lieberman, working with paper cutouts. Karate Kid and Kate Vass gave talks about the history of generative art. We had Ganbrood and Sofia Crespo talking about AI art, before we had done any AI art drops. All the artists had a chance to talk about their algorithms in advance of the mint. That workshop program became a part of the experience in every city that followed.

Mexico City also introduced a new kind of tokenomics. We randomized the mint passes, so collectors didn’t know if they’d get an Iskra or a Pixelfool. That normalized the prices to support the live experience that we want with artists and collectors. Otherwise a Snowfro pass might have sold for 20 ETH—it was his first drop since 2020’s Chromie Squiggle—and another artist’s for 0.5 ETH, which would have created weird social dynamics. Some of the collectors in Mexico City were disappointed because they wanted to be able to purchase a specific artist mint pass on primary. But we were doing a group show, and we didn’t want to have a situation where some works sell out and others don’t. Of course, there’s trading afterward. Markets are markets, and they’re going to reflect what people think is a higher store of value.

These days artists aren’t making money on secondary because most marketplaces and collectors don’t honor royalties. By selling mint passes in advance on primary and giving 70 percent to the artist, we shifted a lot of value away from flippers. We’ve paid out about 7,000 ETH over the last three years directly to artists. I think we’ve really helped the ecosystem grow.

The 30 percent of the mint pass price that we keep goes to producing the experience. We also keep almost all the proceeds from CryptoCitizens. For Venice, we’ve actually reconnected the mint pass and the CryptoCitizens. A golden token for Venice gets you a CryptoVenezian and a mint from the finale collection, which includes around 65 of the artists we’ve worked with. You’ll enter this magnificent Venetian scuola. You’ll mint your CryptoVenezian. Then you’ll go to another room and mint another project from a separate contract. It could be a Deafbeef, an Iskra, a Monica Rizzoli. It’s all probabilistic and all on-chain. It’s a fun way of joining the pixel art with the generative art at the end of our roadmap.

We’re close to completing a three-year journey. I’m trying to stay present for that. Bright Moments started in the depths of the pandemic. We went through the bull market of jpg summer. There have been crazy ups and downs. I know I’m not going to do something like this again in my lifetime. We accomplished something that goes beyond money or status—we said we were going to go to ten cities and we finished what we said we’d finish. I hope the art we supported will stand the test of time as a sort of canon, a time capsule of this chapter in the history of generative art. But what’s most important are the people. We built a diverse team of people from Venice Beach to New York to Tokyo to Buenos Aires. To see folks in their twenties who came of age at a very difficult time during Covid develop valuable skills in smart contracts, web3 marketing, live event production, generative AI—that’s really special. That’s our real legacy.

—as told to Brian Droitcour