Wellness Program

Maya Man’s generative art project about the aesthetics and messaging of self-care memes builds on her exploration of performing femininity online.

Comparisons between the recent boom in popularity of NFTs and the tulipomania of the Dutch Golden Age are so common as to have lapsed into cliché. But it wasn’t always so. In 2019—before anyone but the most dedicated of crypto and tech enthusiasts had heard of non-fungible tokens—British artist Anna Ridler created Bloemenveiling, an online sale of AI-generated animations of tulips, traded on the Ethereum blockchain. Ridler and her collaborator David Pfau built their own decentralized application through which to sell the works and wrote smart contracts coded so that the digital tulips would succumb to “blight” and disappear after a few days of viewing. They also programmed bots to drive up prices in a simulation of the competitive frenzy that once fuelled the tulip market. The project encapsulated new possibilities for commerce as well as their dystopian discontents, embracing art’s capacity to hold contradictions as it gives insight into novel technologies.

The immediate context for the project was the crypto hype cycle, then already in full swing. Looking back today, Bloemenveiling seems eerily predictive of the NFT market that would erupt in the early months of 2021. “Never did we imagine that there might be a market for NFTs even if the artworks which they represented could be freely viewed and shared by anyone,” Ridler has since written. Yet now the vanishing act that the tulips were programmed to perform reads as a canny comment on the manufactured scarcity of art on the blockchain, and on the chasm between the aesthetic object (in this case, the tulip animation) and its speculative value. If you chose not to view the tulip video, it would remain whole. Making that choice would be a little bit like stowing away a Monet in a freeport warehouse: to actually experience and appreciate the work, you would have to accept risk and loss.

The tension between art appreciation and the logic of trading and speculation—when is the right time to buy, and to sell, and for how much?—is made literal.

Since 2017 Ridler—who holds an MA in information experience design from the Royal College of Art in London—has worked extensively with emerging technologies, in particular generative adversarial networks (GANs). She often speaks of her interest in using these technologies not for their own sake but to work through and “unpick” the ideas that shape them. It makes sense that her early work on blockchain technology, which combined an unusually hands-on approach with examination of cultural and historical parallels, would result in such a prescient take on NFTs. In an interview late last year, Ridler said she wasn’t sure she would take it up again. “I hated working with the blockchain. It’s a really complicated technology,” she said.

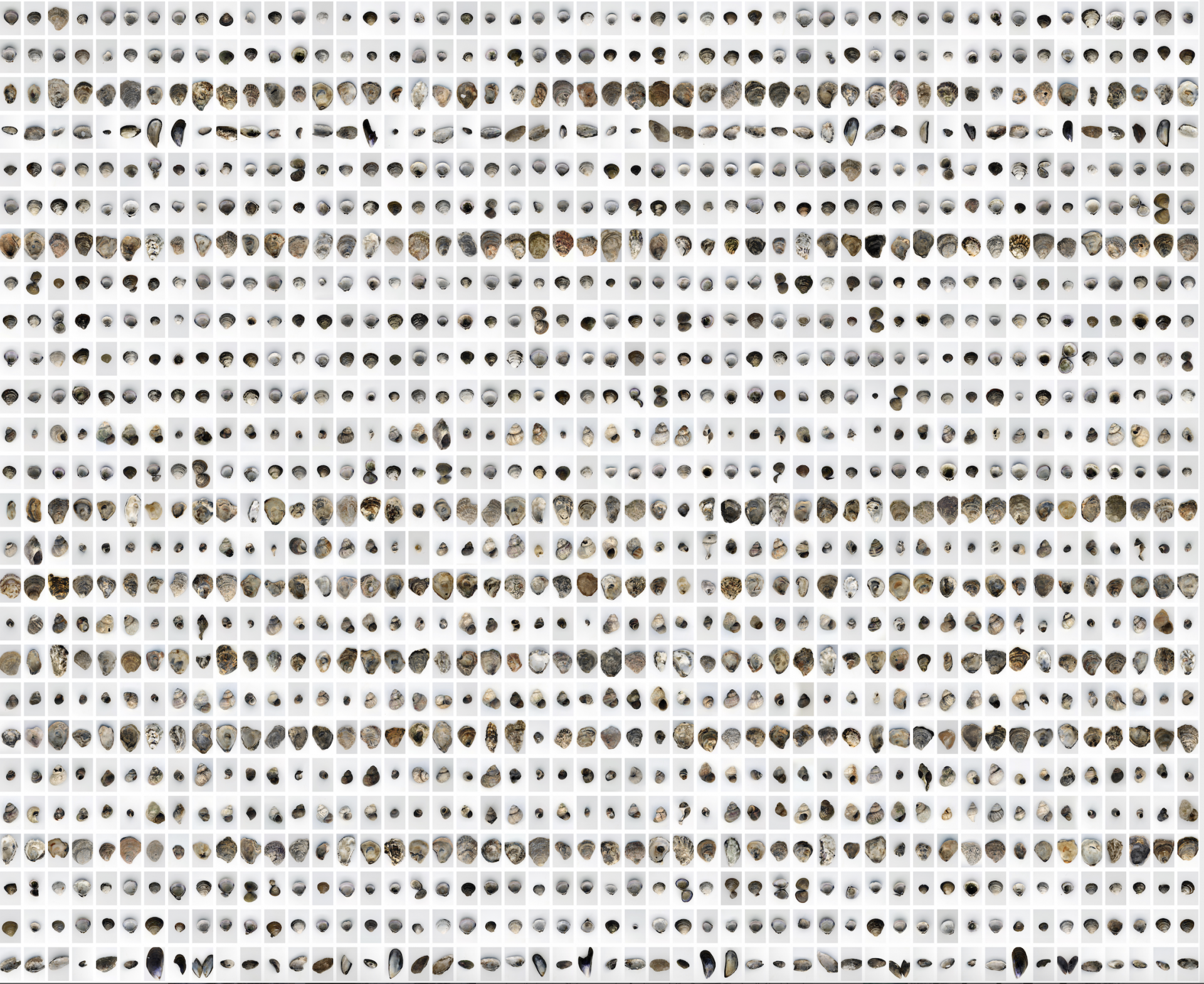

She must have changed her mind soon after. In June 2021, three months after Beeple sold an NFT for 69.3 million USD and the rest of the world learned what “fungible” means, Ridler unveiled her second NFT project. Sold by Sotheby’s as part of an online auction curated by artist Robert Alice, The Shell Record develops Ridler’s interest in what she calls “the history of manias of collecting.” This time her focus centered on the Victorian craze for shells, or conchlyomania. An interest in conchology, especially rare specimens from overseas, emerged in the eighteenth century among wealthy collectors, but by the mid-nineteenth century men and women from all walks of life were combing the shores of Britain, gathering shells for use in handicrafts or to display in specially designated “conchological cabinets.” This is exactly what Ridler did for The Shell Record. She collected shells on the foreshore of the Thames, and then photographed them for the data set—a kind of two-dimensional conchological cabinet—on which she trained a GAN to create the project’s final output: a 30-second animation of a morphing seashell.

Ridler weaves together strands of association, resulting in a tone that is both contemplative and playful. A “shell record” is a technical term used in finance, which refers to a document containing all the details of an item that has been purchased before it has been received (after which it becomes an official “asset record”). The title of Ridler’s work also alludes to the use of shells as currency, which dates back several millennia. This history is the subject of one of the foundational texts in the crypto canon: Nick Szabo’s essay “Shelling Out: The Origins of Money,” originally published in 2002. It is sometimes posited that Szabo is Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous inventor of Bitcoin, a claim that Szabo has denied. Nevertheless, the essay’s theory of “primitive money” or “collectibles” such as shells has been credited as an influence on the subsequent development of cryptocurrency, the most technologically advanced manifestation of an ancient practice. The Shell Record draws out these links between shells, money, and the blockchain. The conchological collection, we are told, was gathered in the shadow of the City of London, a historic financial center home to the Bank of England and the Stock Exchange.

Like Bloemenveiling, The Shell Record offers a commentary on the process by which objects—whether physical or digital, natural, or artificial—acquire economic value within a system of exchange. Here, too, the most sophisticated aspect of commentary is embedded in the method that Ridler chose to sell the work: an NFT auction. The buyer of The Shell Record at the Sotheby’s auction, who acquired it for 100,800 USD, received one png image of the data set and one mp4 of the morphing shell. As with Bloemenveiling, Ridler customized a smart contract, although here the work held the potential to proliferate rather than diminish over time. The contract dictates that the second buyer of The Shell Record will receive two pngs and two video files, and so on, up until the fourth buyer. The new pngs will contain elements of the previous images; the videos will be longer and faster. Once more, the tension between art appreciation and the logic of trading and speculation—when is the right time to buy, and to sell, and for how much?—is made literal. To “grow” the work, you have to lose (that is, sell) it. The original buyer of the work has it listed on OpenSea for 500 ETH, equivalent to more than 2 million USD at time of writing.

This time around, Ridler did not have to create a decentralized application on which to sell the work. As part of a much-touted sale that brought in 17.1 million USD, Sotheby’s minted the work on a platform called Nameless, one of countless services that have sprung up in the past year that allow users to customize smart contracts and sell NFTs. (Sotheby’s has since launched its own platform called Metaverse.)

The assembled data set functions as a record of a particular—and ecologically devastating—moment in time.

By both commenting on and participating in the NFT collecting phenomenon, Ridler adopts a sometimes challenging position. As she has acknowledged, the technologies she uses—both machine learning and the blockchain—involve massive amounts of energy consumption, due to the high-powered computers that are required. When interviewed about Bloemenveiling, she said: “I’ve spent months running something that can now create perfect simulacra of nature, whilst all the time using up the natural resources in order to create it. This is a tension that I haven’t quite resolved.” When I spoke to Ridler about The Shell Record, she said “the tension is still there and is something that I think about constantly.” Rather than suppress it, she places this conflict front and center: environmental degradation is one of the subjects of The Shell Record. The assembled data set also functions as a record of a particular—and ecologically devastating—moment in time. In a video statement on the project, Ridler mentions a scientific paper that inspired her. “Scientists think that shells that have been in the river since the end of the last Ice Age are now becoming increasingly rare and that these are being replaced by new species,” she says. “The change of the shells that you can find along the Thames will become a new time-marker for the Anthropocene.”

For all the ambivalence of The Shell Record, Ridler declines to propose any alternative model for the creation and sale of NFTs. That might be a more practical project—but also a less creatively fertile one. Ridler’s reflexive approach, a dexterous entwining of medium and message, instead serves as a model for what artists can bring to conversations about new and emerging technologies. Neither using them unthinkingly nor telling us what to think about them, The Shell Record simply shows these technologies, for good and for bad, in a clearer light.

Gabrielle Schwarz is a writer and editor based in London.