Silent Speech

In animations of hands offering up poetic inscriptions, Shirin Neshat articulates how the urge to speak has the power to communicate, despite coerced silence.

At the center of the first room of Charlotte Johannesson’s exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary hangs a tapestry: a long vertical creation in purple and fuchsia wool. At the top is a simplified world map drawn in thick pink threads. Below, a woman’s face emerges, itself map-like, picked out with a few strong contours and pools of negative space. It is the artist, half turned to the viewer, mouth open as if to speak, her visage streaked with parallel lines like a printout from a struggling printer. Above her head, a few pixelated words: SAVE AS ART? YES/NO. It’s a pointed question, given the context. Johannesson’s important, unusual body of work—which since the 1970s has combined artisanal weaving with pioneering computer graphics and countercultural themes—is only now getting the institutional recognition it deserves. Some of the pieces have literally been saved, from old floppy disks and studio boxes, to make their debuts here. This tapestry, one of a series made recently in 2019, seems wryly to acknowledge the artist’s shifting status in a changing art world.

Johannesson saw an affinity between programming and weaving: both deploy carefully arranged color markers to construct detailed images on a flat screen.

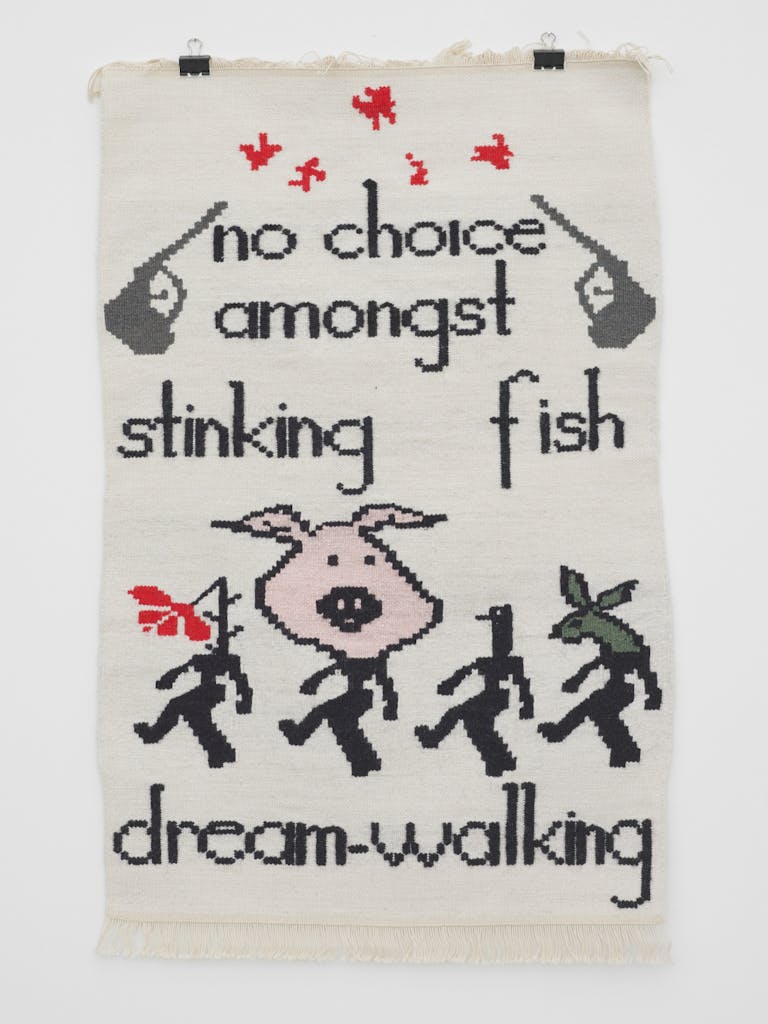

Born in the Swedish city of Malmö in 1943, Johannesson initially studied traditional weaving. But rather than settle into the safe, decorative work associated with the craft, in 1966 she set up Atelier Cannabis, a workshop, gallery, and popular countercultural hangout, with her partner, Sture. There, she crafted politically charged hand-woven textiles that responded to the geopolitics of her time. Works such as Frei Die RAF (Free the RAF), 1976—which depicts the cartoon character Snoopy in fighter-pilot’s attire firing a machine gun at a tank, and refers to the terrorist Red Army Faction active in West Germany at the time—shaped Johannesson’s early reputation as a dissident figure in the Swedish art scene. The tapestry also suggests her underlying interest in digital technologies: Snoopy and his enemy are constructed from vertical and horizontal blocks like early games console graphics, and Johannesson “signs” the piece with her and Sture’s social security numbers, bringing to mind increasingly systematized, computerized methods of state monitoring and control. In 1978, when Johannesson abandoned the loom for the Apple II Plus (one of the earliest personal computers), this aspect of her work really came into its own.

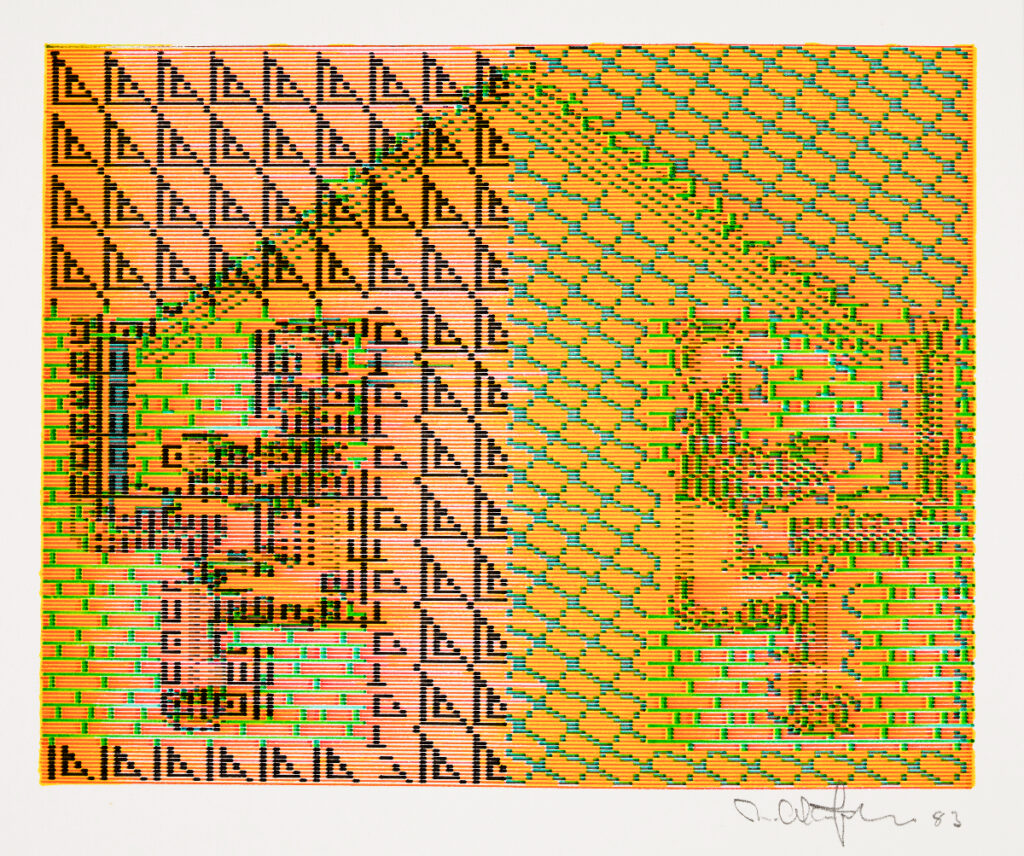

In the absence of graphics software or personal printers, Johannesson taught herself programming to compose her images and transferred them onto paper using an architectural plotter machine. She saw an affinity between this method and weaving: both deploy carefully arranged color markers to construct detailed images on a flat screen. “On the computer there were 239 pixels on the horizontal side and 191 pixels on the vertical side,” she once explained, “and that was exactly what I had in the loom when I was weaving.” Digital art was an evolution of her previous method and the new process, while arduous, suited her. It suited the works, too. The 34 plotted graphics in the exhibition retain the intricacy of Johannesson’s earlier woven pieces, but with a greater sense of technological precision, and they buzz with energy and urgency to match her chosen themes. Take Black Hole (Purple Blue; 1983), a geometric rendering of its mysterious subject that betrays the artist’s fascination with science. Constructed out of tiny, jostling dots of dark ink, the image seems ready to disintegrate at any moment into its atomic parts. A similar shuddering power pervades Rocket (1981–86), which depicts an enormous projectile bursting with cartoonish violence from our world directly towards another Earth, which seems to hover out of reach.

Digital graphics such as these could speak to the technological preoccupations and anxieties of their age more directly than tapestry could. Johannesson’s work from this period also seems to prefigure something of our own networked existence. Take the numerous globes and the world maps, coalescing out of clouds of pixels, a premonition of the World Wide Web. Or the simple, blocky humanoid figures, like avatars or characters in an early computer game, walking purposefully across shifting virtual backdrops. A few works depict synapses firing, and Computer Mind (1984) shows them merging with the electrical circuitry of a computer terminal to form a charged hybrid of human and machine. Staring out from various pieces, too, is Johannesson’s own portrait—her self-image reproduced, enmeshed, and at home in the digital world. These are beguiling images from an artist who seemed to recognize, early on, how digital technology would transform not just our day-to-day lives but our characters and consciousness. In the second (and last) room of the exhibition, several of her designs are blown up and projected in all their kaleidoscopic glory as a slideshow across three large screens. These works were excavated recently from old floppy disks, and the artist felt that the new format captured the feeling of total immersion in virtual reality that she enjoyed when creating the images decades earlier. The ever-changing scenes demand your attention and draw you in to their worlds.

But there’s a danger to reading too much of today’s virtual existence into these works. Contemporary online culture is one of distraction: aggressively optimized, deliberately overstimulating, promising speed and convenience and ease. Johannesson’s artworks—for all their visual energy, despite their jostling overlaid graphics and glitchy aesthetics—emerge from a place of deep focus and slow, deliberate production. The exhibition, which eschews contextual information such as wall texts in favor of a simple hang, encourages visitors to pay correspondingly close attention to the intricacies of each piece. Seen up close in this way, the surface details of Johannesson’s plotted paper pieces really stand out. Every “pixel” is a carefully chosen shape and color, fastidiously arranged like the cross-hatchings of a technical drawing or a delicate piece of needlework. The plotting machine that Johannesson used to make them applied pen to paper twelve times for every mark; the ink pools at the edge of every dot and dash, lending remarkable subtlety and texture to the works. The time and effort that went into these pieces is palpable, and integral to their appeal: it is telling that Johannesson quit her computer-based practice once software advances made the work less hands-on.

With each shift in medium, the texture of Johannesson’s work changes, literally and rhetorically.

Many of Johannesson’s later creations are more obviously artisanal, including a series of hand-made paper works from the 1990s, imprinted with images that seep softly into the fibers, and a new set of hand-woven lace designs (a nod to Nottingham’s historic local industry). Six tapestries from 2019—including SAVE AS ART? YES/NO—have been digitally woven in a neat inversion of Johannesson’s old working processes. There are even two paintings: smoothly finished acrylics on canvas from 2003 and 2006. With each shift in medium, the texture of Johannesson’s work changes, literally and rhetorically. Physical and virtual ideas collide, shape, and reshape each other. Among the recurring motifs in these later works are the camel and the palm tree. To the artist, they symbolize the ancient caravans that used to thread the globe: old networks of knowledge and communication that carried radical ideas far and wide long before modern technology found ways to rewire the world. In works such as Fairy-tale (1992), a work on paper depicting a dream-like desert scene, and Kamel I (2003), a colourful stylized canvas, subject matter and media combine to signal a sort of slowing down, a change of pace and perspective that nonetheless remains closely tied to her wider oeuvre.

Johannesson’s art somehow manages to be both punchy and delicate, technological and artisanal, quick-fire and slow-burning. This is a body of work fizzing with visionary energy, but that also benefits from slower channels of looking, making, and communicating—that has a lot to say, yet will not be rushed. It is heartening to see the art world finally give it a longer look.

Maggie Gray is a writer, editor, and art historian based in London.