For The Record

Arcual is the latest venture to promise that its blockchain technology will transform the art world, but thorny questions remain.

One of the main complaints or criticisms directed against large language models (LLM), like OpenAI’s GPT series and Google Bard, is that these technologies generate seemingly intelligible statements, but they do not and cannot understand what they say. Versions of this have proliferated in both the academic and popular media over the past several months. Consider the following explanation offered by Ian Bogost in an op-ed for The Atlantic: “ChatGPT lacks the ability to truly understand the complexity of human language and conversation. It is simply trained to generate words based on a given input, but it does not have the ability to truly comprehend the meaning behind those words.” Or a similar statement from linguist Emily Bender in a recent profile of her published in New York magazine: “The models are built on statistics. They’re great at mimicry and bad at facts. Why? LLMs have no access to real-world, embodied referents.”

We now have writings without the underlying intentions of some living voice to animate and answer for what comes to be written.

If the terms of these critical appraisals sound familiar, they should. It’s just good old fashioned logocentric metaphysics. Logocentrism, as the philosopher Jacques Derrida explains, is not just one –ism among others; it is a way of theorizing language that gives central importance to the immediate “presence” of the spoken word, thereby rendering writing a secondary and derived technical reproduction, the trace of an “absence.” This way of thinking has had a controlling influence on Western culture’s way of making sense of all kinds of things in philosophy, science, and the arts. Derrida, for his part, does not just challenge the long shadow of this ideology; he pursues and documents its deconstruction. And in doing so, he provided us with a way to think about LLM technology outside the box of Western metaphysics.

In response to a written text, logocentrism has made it reasonable to ask who (or even what) speaks through the instrumentality of the writing and can therefore take responsibility for what has been said. This seemingly reasonable expectation eventually comes to be formalized during the modern era in the figure of the author. As Michel Foucault explained in the aptly titled essay “What is an Author?” (1969), the concept is not some naturally occurring phenomenon; it was a literary and legal affordance deliberately fabricated at a particular time and place in an effort to determine who is speaking

LLMs effectively interrupt this expectation, as it is difficult if not impossible to know who or what is actually doing the speaking in the texts they produce. It is this indeterminacy or withdrawal of literary authority that was already announced and marked by the apocalyptic title of Roland Barthes’s essay 1967 “Death of the Author.” Though Barthes and Foucault of course did not address themselves to LLMs, their work on the “author function” anticipates our current situation with algorithmically generated content. We now have writings without the underlying intentions of some living voice to animate and answer for what comes to be written. Such writings are, quite literally, unauthorized.

Once the written text is cut loose from the controlling interests and intentions of an author (which is, it should be noted, a technical fact of circulation identified by and not the result of innovations in literary theory), the question concerning significance gets turned around. Specifically, the meaning of a text is not something that can be guaranteed a priori by the authentic subjectivity of the one who is assumed to be speaking through the medium of the writing. Instead, meaning becomes an emergent phenomenon that results from readers’ engagement with the text.

Logocentrism actually has everything backwards and upside down.

While the significance that emerges in this process is customarily attributed to the intentions of an author, that attribution is (and has always only been) projected backwards from the act of reading. Thus, meaning is actually an effect that is, in the words of Slavoj Žižek, “retroactively (presup)posited” to become its own presumed cause. And in this process, as Mark Amerika explains in Remix the Book (2011), the artist becomes a postproduction medium. Logocentrism actually has everything backwards and upside down.

Ultimately, the issue is not (at least not exclusively) where meaning is located and produced. What is at issue is the concept of meaning itself. Since at least Aristotle, language has been understood to consist of signs that refer and defer to things. Following this classical semiology, it has been argued that LLMs do not “truly comprehend the meaning behind the words” (Bogost) because they “have no access to real-world, embodied referents” (Bender).

This seemingly commonsense view, however, is not necessarily the natural order of things. And it has been directly challenged by twentieth-century innovations in structural linguistics, which sees language and meaning-making as a self-contained system. The dictionary provides what is perhaps one of the best illustrations of this basic fact: words come to have meaning through their differential relationship to other words. In pursuing the meaning of a word in the dictionary, one remains within the system of linguistic signifiers and never gets outside language to the referent or what Derrida has called the “transcendental signified.”

What is at issue is the concept of meaning itself.

As the philosopher famously (or notoriously) stated: “There is nothing outside the text.” This does not mean—as many critics have mistakenly assumed—that nothing is real or objectively true and that everything is just a socially constructed artifact or effect of discourse. What it indicates is that a text—whether written by a human being or generated by an LLM—comes to enact and perform meaning by way of interrelationships with other texts and contexts. Consequently, what has been offered as a criticism of LLM technology—namely, that these algorithms only circulate different signs without access to the signified—might not be the indictment critics think it is. As viewed from the perspective of structural linguistics, it is an accurate diagnosis of how languages actually function.

LLMs and other forms of generative AI are powerful technologies, and it is necessary to be critical of the opportunities and challenges they present and operationalize. So far, however many of the available responses from linguists, philosophers, and AI experts seek to reassert an already flimsy and failing logocentric metaphysics that has been the operating system of Western thought for centuries. Instead of trying to forcefully reassert the truth of logocentrism and the various exceptionalisms that it has historically supported, it may be more fecund to ascertain how AI technologies participate in the deconstruction of this tradition, providing ways to think and write differently.

David Gunkel is a professor of media studies at Northern Illinois University and author of The Machine Question: Critical Perspectives on AI, Robots and Ethics (MIT Press, 2012).

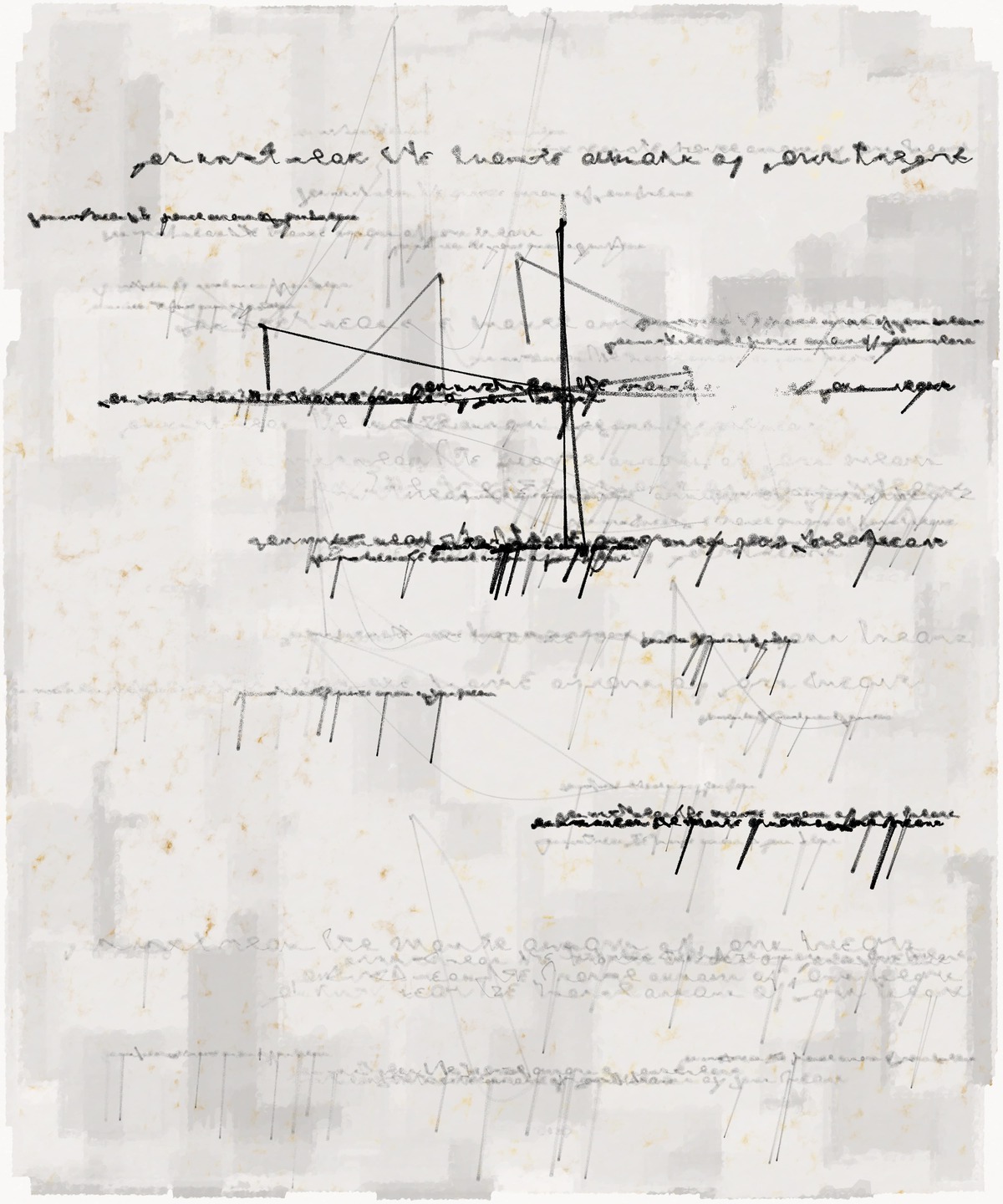

Thanks to Christian Bok and Sarah Ridgely for granting permission to illustrate this article with images from their project “Fifty Days at Iliam” (2022). Bok used the AI writing partner Sudowrite to compose poems derived from Cy Twombly paintings, which Ridgely then converted into asemic script with her code.