Painting the Blockchain into History

Robert Alice endows Bitcoin with the gravitas of inevitability by enmeshing paintings of its founding code in a network of references to histories of art and computing.

In 2008, Damien Hirst sold more than two hundred new works at Sotheby’s, flouting the conventional wisdom that the gallery is the venue for primary market sales while the auction house is where collectors flip works to their own advantage. With this auction of his paintings, drawings and sculptures, Felix Salmon writes in a 2017 New Yorker profile, “Hirst moved out of the world of commodities, which are bought and sold speculatively with a profit motive, and moved into the world of luxury goods, which are bought to be consumed and enjoyed.” Hirst’s direct-to-consumer approach, in this formulation, is inextricable from the work he creates—the market is his medium and the resulting products are diamond-studded (or formaldehyde-preserved) toys.

Salmon paints a picture of the “exuberant present” in which collectors can commune directly with Hirst—and Hirst, in turn, can control his market. If this sounds familiar, it’s probably because you heard something like it from crypto evangelists last year. Though Salmon didn’t have the words for in 2017, he was situating Hirst as a progenitor of the decentralized, peer-to-peer transactions that form the backbone of the NFT market. Hirst’s career-long penchant for disruption makes him a good candidate for a blue-chip transition into web3, a world that prides itself on its unruly nature and maintains an antagonistic relationship with the fustier parts of the art world.

Hirst’s career-long penchant for disruption makes him a good candidate for a blue-chip transition into web3.

Indeed, Hirst launched his first NFT project, The Currency, in March 2021, at the height of the NFT boom, when every artist, brand, and institution was clawing for a chance to drop their own collection. The Currency had the potential to situate Hirst as a sharp critic of the market and a leader of gallery-free sales. But it could have also outed him as a huckster, yet another celebrity looking to exploit the popularity of NFT collections for his own financial benefit.

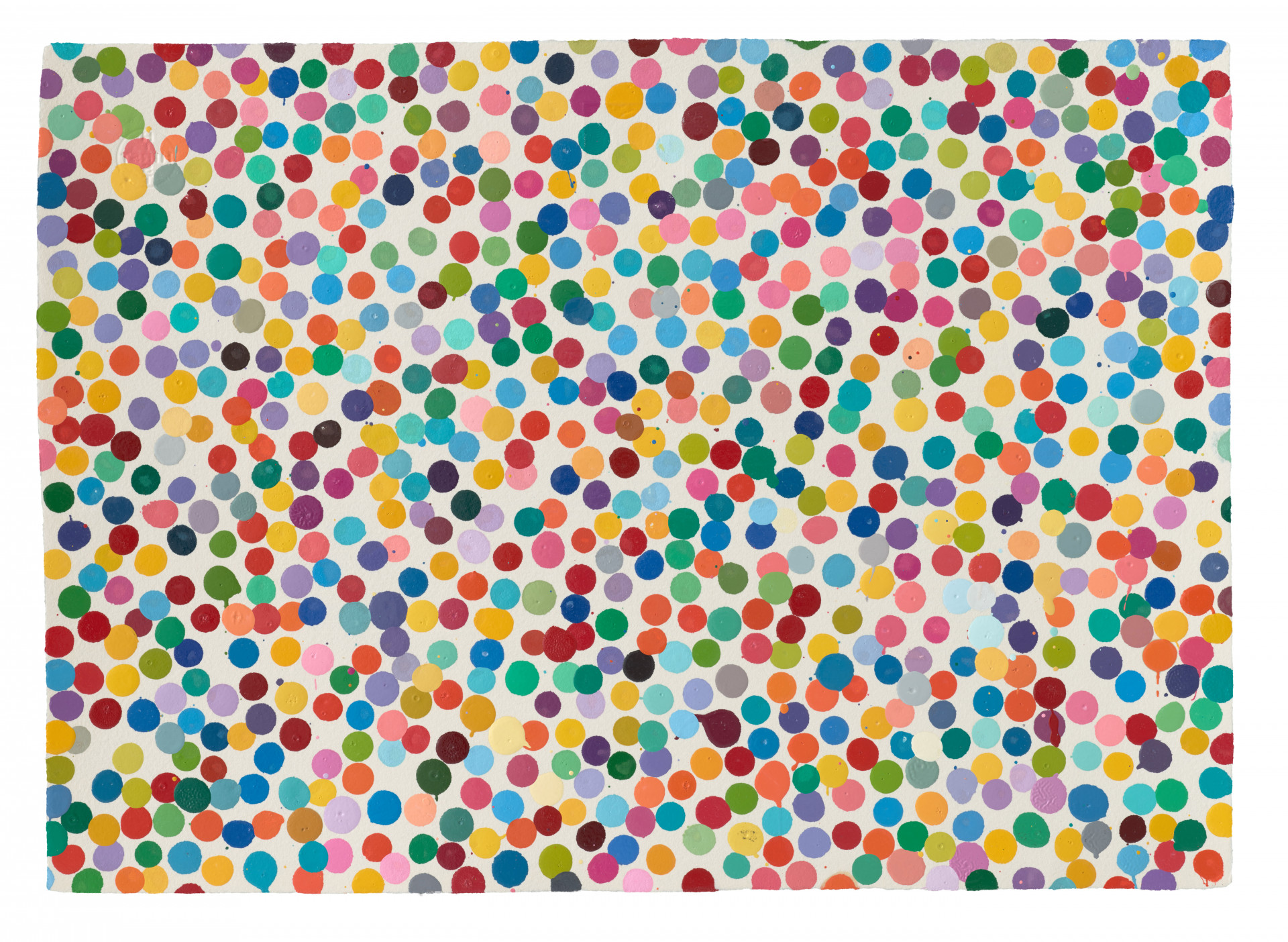

The conceit of The Currency is simple: buyers were offered ten thousand NFTs, which correspond to an equal number of works on paper that were stored securely in a vault somewhere in England. The painted works on paper are continuations of the spot paintings that the artist began creating in the mid-1980s and, more directly, the dot paintings he started in 2016. After purchasing an NFT, a collector could choose whether to keep it or trade it in for the corresponding physical artwork. The one not chosen would then be burned.

The decision Hirst presented—to burn the works on paper or remove the NFTs from circulation—alludes to a long tradition of artists destroying their own work, albeit with a slightly forced participatory wrinkle. When Jasper Johns destroyed his early works in 1954, the artist was on the verge of establishing his trademark style. The destruction was, in his own words, an attempt to “stop becoming and to be an artist.” Gerhard Richter did something similar when he took a box cutter to many earlier works that he considered subpar. Hirst’s proposition lacks the masochism of Johns or Richter, but it does play a similarly cynical game. The older artists’ evisceration of less developed works ensured that their careers would be presented to posterity in the most flattering light, and that their auction prices would not be watered down by inferior pieces. Through the burning process, Hirst does something similar, pushing up the value of the NFTs and the works on paper by reducing the supply of both. The Currency also shares conceptual ground with John Baldessari’s transformational strategies. For Cremation Project (1970), Baldessari dragged much of his past decades’ work to a local crematorium, where it was burned. The ashes were then displayed in boxes alongside a memorial plaque or baked into cookies. Like Hirst, Baldessari was intrigued by the potential to undercut existing hierarchies and to reposition the artist’s relationship to their work.

Hirst’s exhibition devoted to The Currency, on view at Newport Street Gallery through October 30, owes much to Baldessari’s Cremation Project. It, too, makes the destruction of art into a public act, in this case taking place in a “burn room” next to the gift shop on the second floor at Newport Street. Works that have yet to be burned, or which owners have chosen to keep, hang in large plastic sleeves that occupy most of the gallery’s first floor. Those that have been burned are replaced by monochromatic transparencies, a strategy that echoes Baldessari’s decision to create slides of the works he was destroying. By maintaining reproductions, Hirst tacitly acknowledges the primacy of physical over digital work. He’s willing to fully erase the NFT, but when it comes to the works on paper, he can’t seem to stomach eradicating it. Hirst said as much in one of the videos produced by HENI, the company that organized The Currency. “I have a much harder problem burning the paper than I do the NFTs,” he tells his interlocutor, the actor Stephen Fry. Another video featuring Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of England, shows that Hirst has little to say about financial systems beyond their capacity to enrich him personally. In this conversation, too, Hirst privileges the works on paper, referring to them as “actual artworks.” So much for a project that “tests the boundaries of the digital and physical world,” as Hirst said at the launch of The Currency last year.

Hirst has not broken new ground. Instead, he replicates a tired formula used by artists and museums who see NFTs as a way to wring more money out of preexisting works.

Hirst may be well-placed to take advantage of web3’s normalization of direct-to-consumer art, but he’s apathetic to the concept of digital ownership. He claims to be involved in a large-scale investigation into the nature of value in art—The Currency, Hirst tells us, asks the viewer to question how we ascribe value and the limits of digital ownership. But Hirst has not broken new ground. Instead, he replicates a tired formula used by artists and museums who see NFTs as a way to wring more money out of preexisting works.

Other projects that connect physical works to digital tokens, like Sarah Meyohas’s Bitchcoin, do interrogate the relationship between artist and collector. Meyohas does what Hirst claims to do, asking collectors to speculate on her future market. In an op-ed for Artnet, Meyohas cogently breaks down the difference between her project and Hirst’s, exhibiting an excellent grasp on the technology underpinning cryptocurrency and her role in critiquing it. Unlike The Currency, which must be traded in at set periods, Bitchcoin holders can swap their NFT for the petal prints that back it at any point, allowing them to trade off Meyohas’s current standing in the market. Ultimately Meyohas concludes that Hirst’s project is little more than a “CryptoPunks-inspired cash grab.”

The concept for The Currency does feel cribbed directly from the playbook of other successful NFT ventures. As Meyohas notes, Hirst, or someone on the team at HENI, likely knew about the rarities that drive trading of collections on the secondary market. This was a challenge to implement in The Currency. While each of Hirst’s dot paintings is unique, they are functionally identical. No constellation of dots is rarer than any other. To solve this, the works were assigned computer-generated names and ranked according to weight, palette, density of the dots, and even the number of drips. Later in the project, Hirst deployed other common web3 marketing tactics. He created something resembling a DAO, airdropping exclusive tokens to collectors, and started a Discord channel where he appeared for AMAs.

Yet Hirst’s act of destruction sacrifices nothing and risks very little. The physical dot works live on in digital form, reproduced painstakingly online and in the exhibition’s publication, and plastered throughout the gallery at Newport Street as wallpaper. They have not been destroyed, and their transformation into NFTs has been muddied by an abundance of branded detritus.

Meanwhile, in the burn room, several large dot paintings hang around the furnaces, seemingly suggesting that these canvases are also at risk. If Hirst were to incinerate these works, which are unique and hold significant market value, it would represent a genuinely radical move. Not to worry, Hirst’s PR staff reassured me during my visit: those paintings are safe.

Jonah Goldman Kay is a critic based in London.