Simon Denny & terra0

How do smart contracts enable nonhuman entities to govern themselves? Can the law accommodate the systems that blockchains make possible?

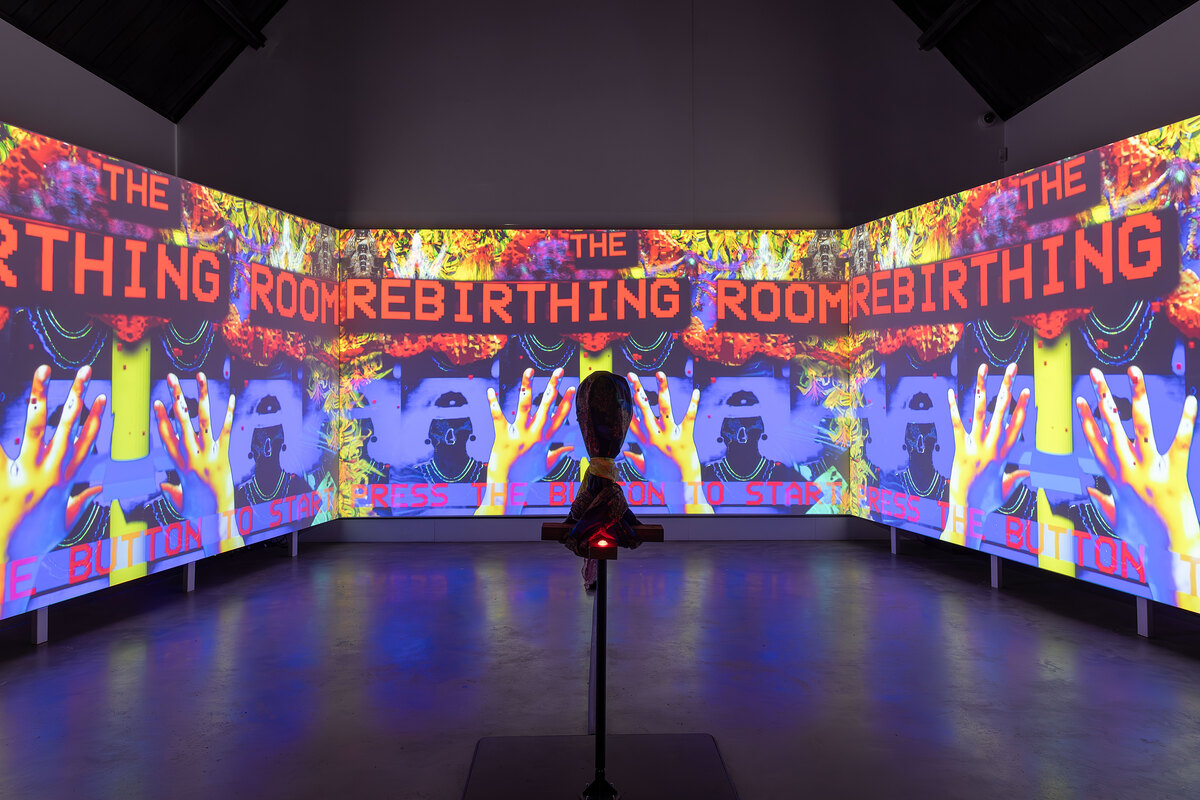

If there is one thing a game always requires of you, it is to participate. This active involvement is very different from what might conventionally be expected of a viewer in a gallery or museum. Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley and R.I.P. Germain are two artists who make use of the interactivity of gameplay, in order to compel the viewer to engage differently with the questions raised by their work. Brathwaite-Shirley’s video games, playable both online and as part of gallery installations, have centered on the lives of Black trans people, drawing on the artist’s own experiences as well as those of her wider community. The issues explored have grown increasingly thorny over the years; one recent work, THE REBIRTHING ROOM (2024), asks players to confront the ways in which they are personally responsible for their problems rather than only blaming societal obstacles. R.I.P. Germain’s multidisciplinary practice similarly draws on both personal and collective experiences—in his case, of Blackness and masculinity. The resulting works often take the form of immersive and highly detailed installations with participatory elements including, in one recent instance, a video game based on the artist’s own close brushes with death. Outland brought the two artists together for a conversation about the shared strategies and themes of their work.

DANIELLE BRATHWAITE-SHIRLEY When I was growing up, art never seemed like something that could be a career. But then I ended up doing an art foundation course and I quickly abandoned my plan to study physics. At first, my approach was to try to replicate someone like Picasso. I thought art was spending months in the studio alone painting—until I started meeting people in the burlesque scene: Travis Alabanza, Munroe Bergdorf, Rhys’s Pieces, Rebekah Ubuntu, Sadie Sinner, Alok. They approached art as a career: I need to make rent next week, so I need to make work and put it out in the world.

I started basing my work on these people, who were invisible to society but very visible to me as they were my friends. I began to make work about what it means to have our identity—being trans, queer, being people of color—and to be treated in a certain way due to that identity. And I started to think about what things were missing in our world that I wanted—such as an archive for us, a video game for us, a film for us. And from there it blossomed out to what I do now.

R.I.P. GERMAIN It’s funny that you mentioned physics. In college I was studying to become an architect, and I studied physics as well. Art for me as a child was just something I did every day but it didn’t feel like a viable option to make money. And looking at the industry I would have entered into, at the time I didn’t feel that there was anyone like me in it, from a class or racial perspective.

So for several years I wasn’t making art—or if I was, it was on a subconscious level, like at one point I started trying to make clothes. I even got a grant from the Princes Trust. But I was also just living a regular life, working regular jobs. I always joke that my now partner bullied me into making art again. We were friends from university, we lost contact, and then years later when I was working in an airport she got in touch out of the blue to ask if I wanted to work in her studio. Later she started her own gallery space and said I had to stop working for her so I could make art. She said, “I’m not letting you not make art anymore. You’ve got a show here so just get on with it.” When you’re making the works for that first show, you start to get a maniacal urge to produce and it becomes integral to your core. Once I started making art for the second time I finally realized I couldn’t function without it, even if I never showed work in public again.

BRATHWAITE-SHIRLEY Yes! It does start to feel like even if my career failed I’d have to keep doing it, even if it doesn’t feel good. It’s like a cruel mistress.

The first things I started to make after the paintings were digital drawings. It was a time when digital art wasn’t very big yet. But the works didn’t really do anything. It wasn’t until I started making films that I found a language that made sense to me. I could get a reaction from my work that wasn’t a psychological assessment of the work but more of an emotional response. My first film, BLACKZILLA (2018), is an animation which asks people to think about what it would be like to live on a planet where only Black trans people could survive. It has both laughter and super low moments of sadness, because I want to get people to flip between those emotional states.

After that film, I started making animations which would contain fake video game choices. I would almost call them concept art for video games because they’re very similar to the games I make now, except the choices were faked. I wanted to play with making the choices visible but then not picking the ones I thought people would want to pick. But then one day someone watched one of my films and they said to me, “I find that film very beautiful and I like that it’s beautiful because I can ignore what you’re talking about.” That’s when I decided these things could no longer be passive. They should be an active experience, where you have to make a choice. Making games and interactive work—work that challenges the audience—came to the forefront for me. I realized that if I really care about the concepts I’m thinking about then the audience needs to have a harder decision going through the shows then they usually do in our institutions.

R.I.P. GERMAIN It wasn’t until about a year ago that I realized the first work that I presented in a gallery, Tyson (X) (2018), was basically a snuff film. In the summer of 2018, there were a lot of kids in London dying due to violence. I was very involved with the drill scene in the UK, and it was becoming quickly apparent that a lot of the kids in this scene were either getting locked up or killed. But it wasn’t being covered in a critical, complex way. I’d spent months following all the gangs on their social media accounts—that generation has a different relationship to privacy. They really do not give a fuck about what they are uploading onto these platforms because most of these clips are being used as taunts against their opps, and quick and easy ways to flaunt what they’ve done. I had footage of bank robberies, jailbreaks, stabbings, everything. I made karaoke videos and used these clips to make background visuals, accompanying songs which were talking about doing the same things the videos depicted. I then challenged audiences to get up on stage and sing the songs that I knew they liked—obviously no one did.

Since then, a big part of my practice has been focused on that dialogue between myself and my audience: it’s about how they participate in the work, whether through passive engagement or overt engagement. Sometimes I want more passivity and sometimes I want more of a forced engagement where you have to do something in order to activate the work. In my interactive installations, there are all these sounds and smells. You might have a video game to play, objects to pick up, or puzzles to solve.

BRATHWAITE-SHIRLEY When I taught myself how to make games, I did it like a diary. Each day I would go into Blender’s game engine and record something about my life or my friends, and then I would try a bit of the visual scripting—for instance, “W to move forward.” I was learning all about logic, choices, how much freedom to put in the game, how much active time, how much passive time. It was also extremely helpful in understanding that I need to make sure that the artwork is the path through the game, not the thing you see. The real artwork takes place inside your body and everything else—the visuals, the sound—is just a way to get you there. You shouldn’t leave with the images of the game, you should leave with the feeling that you had when you made those decisions in the game.

Later I started working with coders and talking to them about how to make a game properly. And I did a lot of work with the community to figure out what the choices in the games should be. Those conversations allowed us to ask questions like, if you’re trying to center a certain group of people, should there be an option to pick your identity? How much should be missed if you pick a certain gender or identity? Should it make you feel safe or not safe? Is the environment that you’re playing in important? Should the game be online? Should it be offline?

R.I.P. GERMAIN Being an avid gamer, I’ve always had a huge respect for the amount of skill and expertise it takes to make a game, regardless of how big or small the game may be. For the game I made, I knew I would need help in order to get it to a level I’d be happy with, so I worked with a coder. I designed everything, though—I designed the layout of the rooms, the dialogue trees, the “levels” that you go through. Like you, I wanted the player to feel exactly how I felt, because the game that I made was based on real-life events, although you play in surreal environments.

There are six minigames within the main game, based on six near-death experiences that I’ve had. The dialogue trees are real conversations that I’ve had. I remember them all verbatim. The difference in the conversational paths then becomes an analogy for how precarious Black life can be. With a choice like “…you alright?” or “you alright!?!,” I understand the difference, but someone who doesn’t usually have those experiences may not get it. The main goal of the game is to force the audience to engage with life experiences that they usually have the privilege to avoid. I’ve had a lot of people say to me this game is hard. Well yeah, think about the people who have to live it and how hard it is then to make it to an adult age with your mind and body intact.

The game is called A Saaarf Demo (2022). At the time I had ambitions of making a full-length video game, so I thought this could be a demo of sorts. And “saaarf” is a phonetically strained take on “sawf,” Jamaican Patwah for “soft”—like, weak. I wanted to investigate aspects of Black masculinity that I’ve had lifelong struggles with and explore what it means to show “weakness” versus strength. You know, like, if someone is approaching you for a satchel that you’re carrying, is it really weak to just hand it over if you’re not going to be pressed about replacing it? Conventional Caribbean machismo culture would say that you are weak if you do that, you shouldn’t give up anything, under no circumstances whatsoever. And I didn’t when I was in that situation. But sensible logic, especially now that I’m a father, dictates I just give up the bag so I can go home to my daughter. A lot of people have died over holding up this trope of hypermasculinity.

BRATHWAITE-SHIRLEY In a way, I feel like my practice is an escape room—and if I could lock people in I would. Like, that’s what I feel like, I’m locked into a certain way that I’ve had to have to live my life. I made the game GET HOME SAFE (2022) while literally trying to get home safe. I would fake being on phone calls and sing into the phone while getting propositioned, being followed home by cars. That was the technique I used to collate the material for the game, but it was also a whole game in itself, a strategy for keeping me safe.

Something that I find very interesting as a parallel in our practices is that the game does not begin and end at the obviously “interactive” portion of the works. I think that’s the difference between a video game on a console and a game in art—the latter doesn’t have to start when you sit down and press a button. It can start when you read the exhibition text, see the colors on the wall, notice how the floor feels, the smell in the gallery. My installation SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE (2021) is a good example of this. Before I get you to play the game, I’m trying to get you excited to pick up the gun, which is used as the controller. It’s the first thing you see when you enter the curtained space where you play the game. The idea is then to talk about these feelings of excitement that come with seeing a gun. I’ve had friends who joined the army and are dead now because they wanted to be in Call of Duty.

A lot of people told me that my game felt impossible to complete. It’s very possible to complete but you just have to work hard. That’s another parallel, I think, with your work. The whole point of it is that it is rough. The more time people spend with it, the more they get out of it. Often in the art world the opposite feels true. The work does everything for us, we don’t have to do anything. But especially with your work, I feel like people miss so many things in your shows, don’t they? They don’t realize how many clues you have left everywhere, because they’re in gallery mode.

R.I.P. GERMAIN Exactly, and that’s the point: highlighting and trying to undo how we’ve been raised to conventionally engage with an art space. Speaking of guns, I’ve presented three real guns in shows that audience members could have picked up easily. But they’ve chosen not to. I believe this is because they see art as precious objects that they’re meant to passively observe and not touch, even when there’s an overt offer to do so. In a gallery there are these conventions that set up a barrier between the audience and the points you’re trying to get at. People think of the gallery as a safe space but the topics we’re trying to approach are for us, in lived ways, not safe spaces. We’re trying to show how various aspects of who we are mean that when we go into the world, life has the difficulty settings turned up a notch or two.

It’s interesting how you talk about how you situate your work in its environment, anticipating how people will engage with it and playing around with that. I do the same thing. When I showed A Saaarf Demo as part of “Jesus Died For Us, We Will Die For Dudus!” at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, I placed it in the back of this trap. There are weights, there’s a scooter, there’s a weed grow. People are always doing things like playing video games in those types of places. That’s how they pass time. These are also places that are run by hypermasculinity. The idea was to create a space that replicated that atmosphere and its tropes, and then put a game in there that’s trying to discuss and dismantle those tropes.

When I first presented that game back in 2022 at Two Queens in Leicester, I recreated a fake newsagent’s that I had come across in east London, which was actually an elaborate cover for a peephole drug depot. I worked with Ezra-Lloyd Jackson, this amazing perfumer, to try to create a scent that invoked empathy when you smelled it. So when people entered the room they were already in the right frame of mind to be open to new ideas and feelings, and not to come in with their preconceived biases and sit stubbornly in them.

I completely reject likening my installations to escape rooms. I’ve never used that term when discussing them nor tried to build them within that framework—it’s just that with the scene I’m talking about, the security parameters that they put in place, the hoops that you have to jump through in order to gain access into these spaces, the experience can be likened to an escape room. For instance, you can’t wear hats, you can only come in groups of two at a time, etc. That’s just the nature of those spaces. And they exist because the needs of a large portion of the people that frequent these places aren’t being catered to by mainstream government services, so these illicit “community” spaces are flourishing instead.

BRATHWAITE-SHIRLEY Talking of safe spaces: in the past, I’ve made a lot of work that has made people who were uncomfortable feel more comfortable and people who were comfortable feel challenged. Now I’m trying to make work that kind of challenges everyone.

R.I.P. GERMAIN Yes! You and I are in the same place!

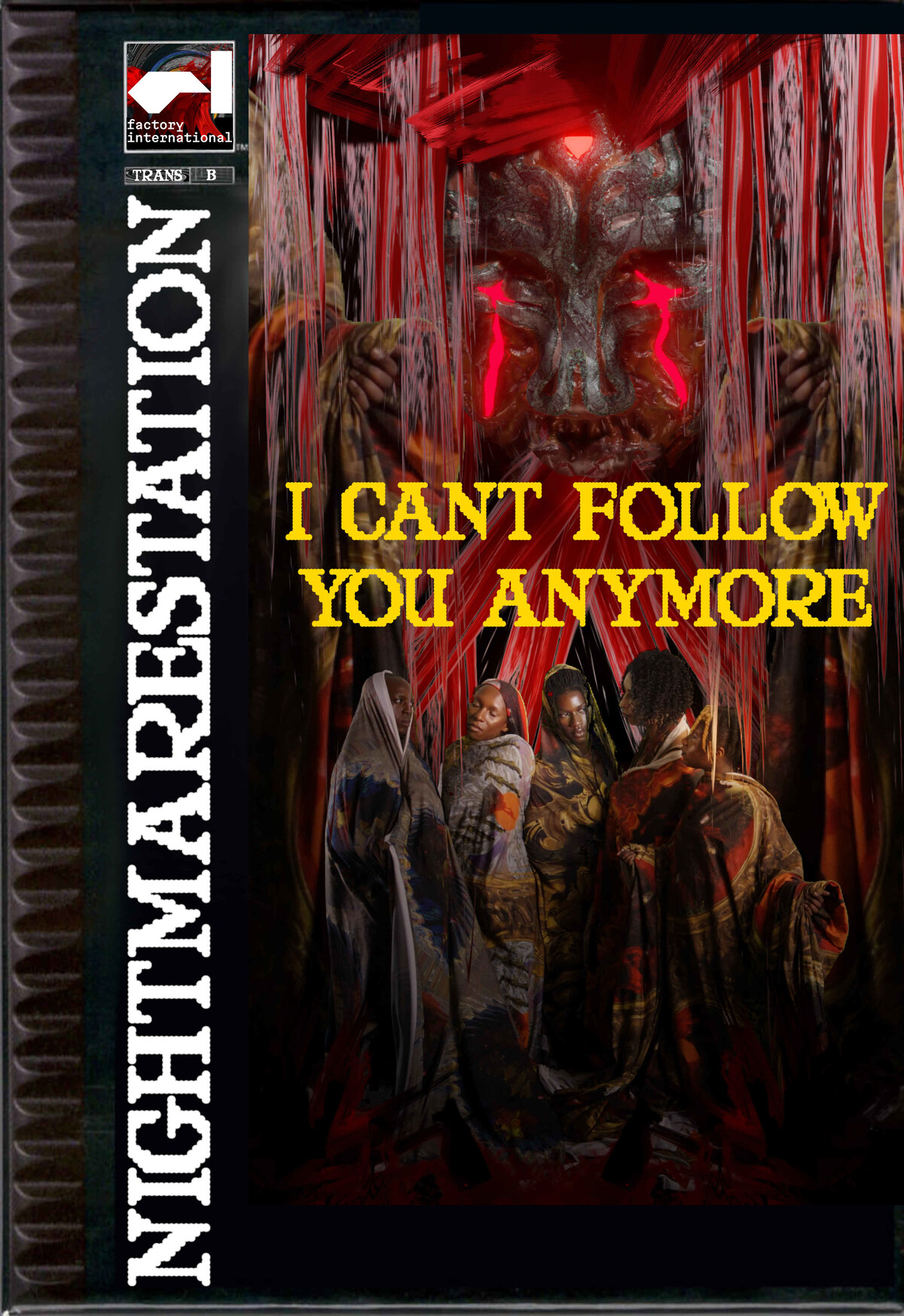

BRATHWAITE-SHIRLEY I made a game last year called I CAN’T FOLLOW YOU ANYMORE (2023). It’s all about how I used to deify, and still do sometimes, Black trans people—and how that put me in dangerous scenarios. I was told that I was in a safe space, because everyone had the same political ideology that I had. But I’ve found that this mindset is actually really dangerous. You’re not allowed to present honesty, messiness, questioning—you must present full and instant clarity and acceptability on all matters, which I think is impossible and unfair. The game is about a Black trans person who leads a fascist movement in order to liberate Black trans people, but they don’t know that the way they’re leading these people is wrong. The idea of the game is to get you to stop playing. It comes to a point when you either keep playing and you subjugate your followers, or you stop playing and they lead themselves.

Another game I made recently is THE REBIRTHING ROOM (2024), which I made for Studio Voltaire in London. In that game you fight all the reasons you’re failing—self-doubt, anxiety, fear of failure, self-loathing, etc. I made it because I have a lot of friends who were blaming society for all their failures and I was looking at them and thinking, yes, well, but you’re also dealing with your own stuff. It’s not that external factors aren’t holding you back—but you are also holding onto certain things because society has been so hard. It’s basically a room to try to admit the shit that’s holding you back that you’re doing.

One more project I’ll mention is NO SPACE FOR REDEMPTION? (2023), which I showed this year at the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. It’s about nightmare scenarios that have no good ending. They’re based on nightmares I’ve had. The whole point is to create challenging situations that I find messy to think about and don’t have clear answers on. There’s one where someone trying to get you to jump off the roof and kill yourself so they can use it as content. In another, your friend wants to have sex with you, until a famous person comes along and they decide they want to have sex with the celebrity instead.

That’s all to say that the new work I’m endeavoring to make is work that I find difficult to think about and am terrified to show.

R.I.P. GERMAIN Haha, welcome to the flock! That’s the space I bathe in when I’m thinking about the work I want to make. It’s worth making if it scares me, if it feels like everyone could hate it.

I’m not really interested in distributing an ambassadorial take on a culture or a people. My interests lie in acknowledging a reality I see, presenting the messy in it, and wanting to create a discussion around what I feel needs to change. The messiness is where I think you can find the most profound answers and new leads to forge a path forward with. It comes back to what you were saying earlier about an audience member looking at one of your videos and saying they can avoid the critical dialogue that you’re trying to instigate, and you starting to make games in the manner that you do as a response to this.

BRATHWAITE-SHIRLEY That’s why I love games or interactive shows: they make the audience part of it. They’re not just a witness to it. I always have this phrase: I’m not trying to make art, I’m trying to change art. I don’t know if I’m necessarily managing it but that’s the goal.

—Moderated by Gabrielle Schwarz