Simon Denny & terra0

How do smart contracts enable nonhuman entities to govern themselves? Can the law accommodate the systems that blockchains make possible?

Artists have been using the internet as a space for performances and other kinds of interventions as long as it has been available. But as general habits of internet use have changed, so have artists’ approaches. In the conversation below, David Horvitz and the duo Mendi and Keith Obadike reminisce about their early projects from the late 1990s and early 2000s, a time when it was more common to go online and seek information about unfamiliar topics. These days, the internet seems—as Mendi Obadike puts it—“more public and less public at the same time,” dominated by platforms that control how and what we see even as they make it easier for us to connect. In this media environment, the artist’s challenge is to create spaces that encourage reflection, and help people feel information more deeply. Horvitz kicked off the conversation by talking about his Wikipedia interventions, which led to an exchange about the artists’ conception of the internet as a space for action and how their sense of what actions are possible there has shifted over time.

DAVID HORVITZ Public Access (2010–12) was a project where I drove up to the California coast and made photographs of me standing on about fifty different beaches, from the Mexico border to the Oregon border. I uploaded the photographs to the articles about those beaches on Wikipedia. I called it Public Access because Wikipedia is a public space, and also California beaches are all publicly accessible. So it was a play between the digital commons and public land.

It came from thinking about performance as putting the body in public space, and the history of Californian conceptual art and performance—artists using their body in the work and documenting it with photography. I was also really obsessed with the idea of photographs taken in public that happen to capture a random person—here’s a photograph of the Statue of Liberty, and there’s someone there. It’s almost an existential kind of thing: someone is just living their life and they get caught in an image. You don’t know who they are. From Wikipedia’s point of view, the purpose of photographs is to have an image of the subject of an article. The image I contributed of Borderfield State Park just happens to have a little silhouette of a person standing there, who happens to be me.

MENDI OBADIKE Yeah. I like that.

KEITH OBADIKE Have you worked with other people as the body in these kinds of projects?

HORVITZ I have worked with other people, but for these specifically I wanted the body to be mine, even though I’m a silhouette so you can only see me from behind. I know it’s me, and the art audience knows it’s me when the work is shown in a gallery or a museum. But for someone who sees it on Wikipedia, it’s just a figure. It could be anybody.

K. OBADIKE What informed your ideas about the internet as a public space?

HORVITZ It’s a little weird about talking about this project because it’s over ten years old, and our perceptions may have changed. I ended up getting banned from Wikipedia, and that became part of the work. The Wikipedia editors saw me as an artist out of control. They wanted to control me. I saw a parallel to what was happening in Malibu at the time, where the beaches are public but property owners hired guards to block access points. The state took the people’s side, and opened up a little staircase that goes down to Malibu Beach. In an unexpected way, the banning shed light on how Wikipedia works. It’s public and we’re participating, but there are layers of control. Behind the scenes there’s this whole culture of editors.

M. OBADIKE Was there a formal response from Wikipedia?

HORVITZ No, editors make decisions and enforce them without informing you. I only found out because someone who was a fan of my work emailed me a link to the editors’ discussion board, like Check this out. They’re talking about you. I naively thought I had been doing something helpful. The article for Pelican State Beach, the northernmost beach in California right at the Oregon border, did not have an image. And I gave it an image. But the conversations about me were crazy. There’s an official process for banning someone. They can’t just do it arbitrarily. They need to find a reason and then discuss it. One of the reasons—which I don’t even really understand—is that I was “making a point.” Another was sock puppetry, when you have multiple accounts, which I was doing.

Some people argued in my defense. There was one comment where someone downloaded my image and then blew it up in Photoshop. They said that since you couldn’t see my face even when the picture was enlarged, there was nothing wrong with it. Alex Provan, the editor of Triple Canopy, got involved in the discussion to support me. But then another Wikipedia editor found a photo of me and Alex on Flickr from 2005, and said Alex’s argument was discredited because he’s my friend.

M. OBADIKE That’s wild.

K. OBADIKE We also had an experience of getting banned. Our project Blackness for Sale (2001), which placed an ad for my Blackness on eBay, got kicked off the site. It was just a form letter from a bot saying, We’re pulling your thing down. Here’s why. I put it back online and we got another automated response. That went on for several days.

At the time, in the ’90s and early 2000s, it felt like there was more open space online that wasn’t so overtly controlled by large corporations. We thought of the projects we were doing online as public artworks or interventions. Because there were fewer big institutions controlling what we engage with, people could stumble onto works and have interesting, sometimes awkward interactions with them, like you want with real public art. You want people to be able to engage with something, fiddle with it, look at it from different angles, sit with it a while. Now the way people behave online has changed in many ways, and one of the biggest changes is the amount of time we spend on any given site. The attention economy has changed. So it’s a very different space, if it is still public at all.

M. OBADIKE On the one hand there’s more corporate ownership of the spaces where people spend time online, but we think of it as more public than we did in the ’90s and early ’00s. Back in the day, you would go to personal websites, business-owned websites—they were more attached to an entity, and less public-seeming. But having your own website meant you could say whatever you want, whereas now you go social media platforms and people think the companies that run them are responsible for what people say, or should be responsible. So it’s weird. It’s more public and less public at the same time.

HORVITZ That’s great. I never thought about it that way. Do you still make work on the internet?

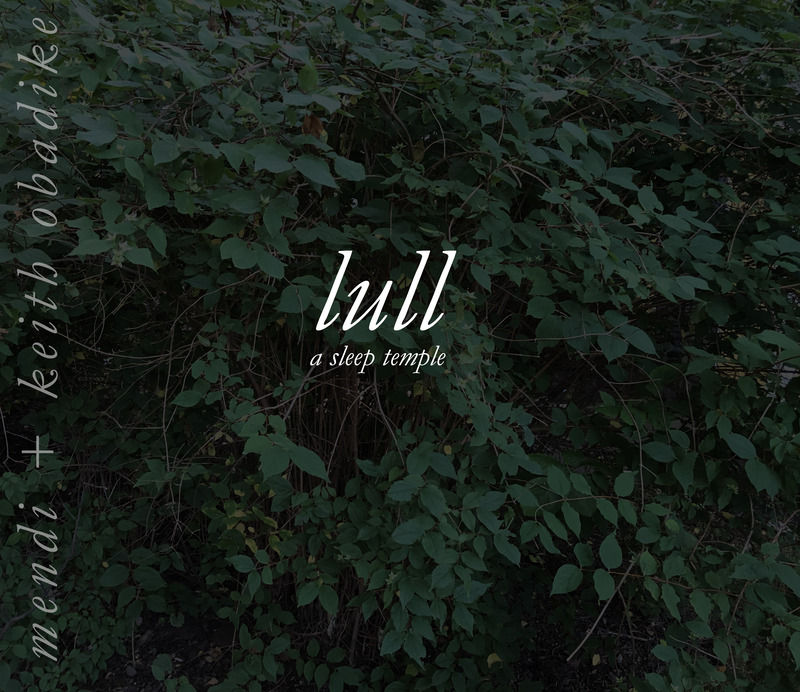

M. OBADIKE Yeah, during the pandemic we made Lull (2020), an eight-hour overnight sleep piece that streamed to different platforms.

K. OBADIKE Around the time of George Floyd’s death, people were starting to go out to the street to protest. People in the media were talking about a “time of unrest.” So of course we were thinking about rest. We’d been talking for a long time about making a live event where people could come sleep. So we decided to do it online. We wrote an eight-hour piece of music with text and we streamed it. Originally we did this with the Gray Sound series at the University of Chicago, then later with the Look + Listen Festival in New York. Some people stayed up and had dialogue with us all night. Some people just went to sleep—which was the point!

HORVITZ But were you asleep?

K. OBADIKE Yeah, we went to sleep eventually.

M. OBADIKE There are patterns in the music. There’s an invitation to slow down your listening. Then there are voiceover parts that are more story-like, with space between words. You really have to fight to stay awake during some of those parts. As it ends it wakes you up. We usually fall asleep and dream and wake up in the same places.

HORVITZ Because it’s on the internet, not everyone’s going to be in the same time zone.

M. OBADIKE Yeah, some people wrote to say they wished we would stream it at another time. And we did it three or four times, for different cities around the world.

K. OBADIKE We did other streaming projects—Difference Tones (2022) with Buffalo AKG Museum and Lift (2021) with the Yale Center for Collaborative Arts and Media. We don’t currently have plans to make something else for the internet—it’s a different place now. But who knows?

HORVITZ It’s interesting because I made all my work on the internet in the early 2000s, when I was in my twenties. It was an accessible place for me as a young artist to start doing something publicly that would have an audience. As I get older I don’t know if I have less interest or less time or just fewer illusions.

M. OBADIKE It’s just changed so much. It doesn’t mean the same thing. We did start getting more opportunities in physical spaces, but I had no plans to stop making work online. But everything around it changed. And then I was like, do I want to say something in this environment? Not yet.

K. OBADIKE We changed a bit, too. Our lives are busier now that we have kids, so when I have time to make stuff I want to get to a different space. I’m often trying to step away from the computer.

M. OBADIKE A lot of the young artists I talk to feel like they have to market themselves on the internet. When they have something they want to say from their hearts, it goes in the same space where they feel like they have to be present to be relevant. That’s very different from when we started out on the internet.

K. OBADIKE I think there’s a lot of great stuff on Instagram, maybe TikTok. But I’m not sure how much self-awareness there is around the containers that people are putting the work in.

HORVITZ I’ve spent the last three years making a garden. I was recently asked to teach a post-internet class at the University of California, Riverside, and half the class will be about my garden, because that’s post-internet for me.

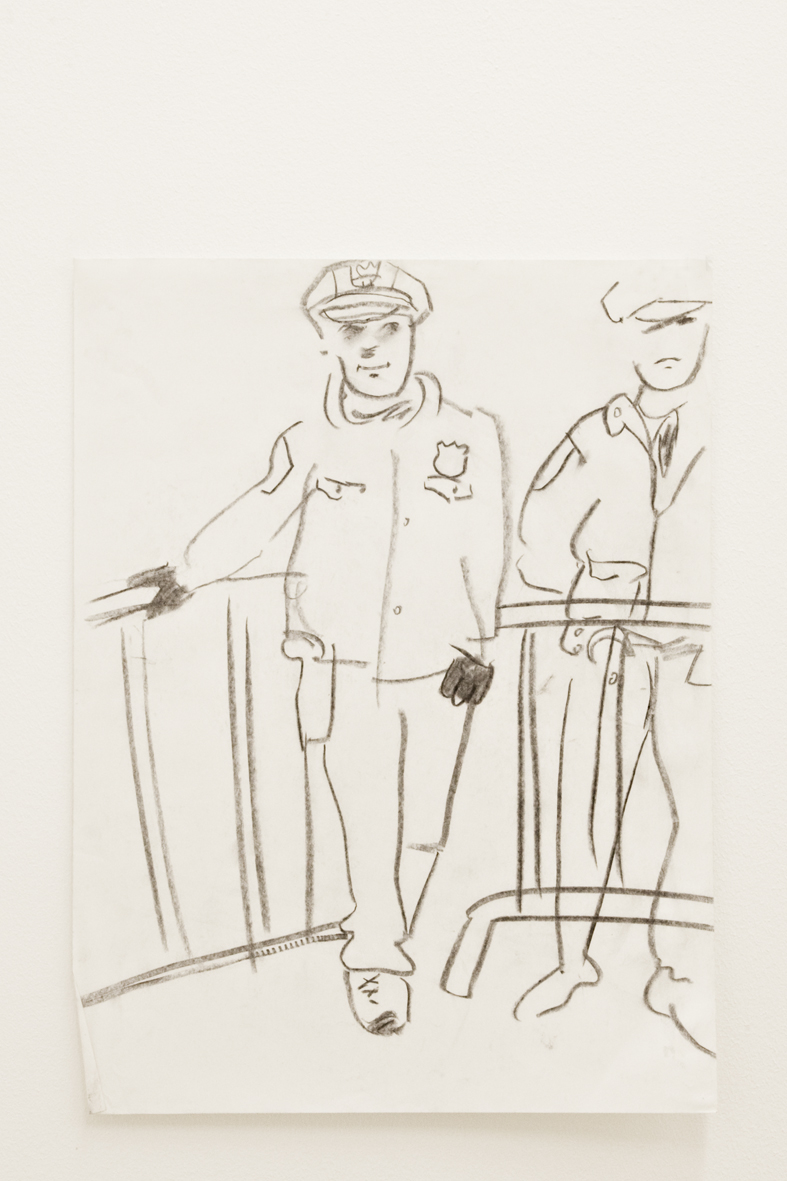

Working online ends up affecting the way you work in other spaces. Around the time of Public Access the Occupy Wall Street movement started, andI went to Zuccotti Park and organized life drawings sessions using police as models, and their “pose” was watching us. We were returning their gaze, or responding with a different kind of gaze, by looking at them and sketching them. The park is a “privately owned public space”—a New York real estate term I still don’t quite understand, though I could see a parallel at the time to the ownership structure of social media.

K. OBADIKE Certainly the way that we worked online shaped how we do things in physical public spaces. A lot of our projects in public will have nodes of different areas of activity. I think that came from the concept of hypertext, a way of making things available to dip into and out of while you’re engaged in a larger piece of text or experience. Does that sound true to you, Mendi?

M. OBADIKE Absolutely. At the beginning I think we talked about wanting to translate the experience of hypertext. We were very conscious about that. But since then it has just been how we work and how we think.

K. OBADIKE One of our first semi-public sound installations was Big House / Disclosure (2007) at Northwestern University in Illinois. We were using data from companies that had profited from the transatlantic slave trade—contemporary companies that descended from companies in the 1800s that insured slave owners or somehow traded in slaves themselves. We were tracking the stock prices of those companies. And as those prices would rise and fall, that data would change this 200-hour house track playing in a building at the university.

M. OBADIKE And it was streaming online.

K. OBADIKE There were other aspects of the project, too. We had some performance scores that we made, with poems and photographs and other little components. That was our first step in taking ideas from online projects, where we had all these different things on a website. Big House / Disclosure was in 2007and we continue to do multinodal projects, pulling data from the internet in order to make things happen in physical spaces. Later on, we got to using databases. In the “Numbers Station” series (2015–), we take databases with information about stop and frisk and things like that and sonify them.

M. OBADIKE We also did a project called Fit (2016) where we were tracking the search for the phrase “Black Lives Matter.” It was about how you could tell what was happening based on how often people were looking for that phrase. It wasn’t something that happened online, but it was data that came from the internet because of what that said about the public watching certain deaths and certain trials.

HORVITZ Were you tracking that regionally?

K. OBADIKE No, we were looking at Google in general over time. You could see the peaks and valleys. When someone got killed by the police it would become a big news story, and then interest in it would sort of fade away.

HORVITZ That raises questions about who is searching for it and why, and what comes up when they’re searching. There’s also predictive search, when you start typing and it fills the rest in for you, and that changes depending on location—if you’re in New York or Iowa, it predicts what you want depending on the trends in the area. Recently I was entering a question about Japan into the search bar and one of the suggestions was “Why doesn’t Japan hate the US?” It blew my mind.

M. OBADIKE And you just don’t know the purpose of the search, whether the person is really interested in what they’re looking up or repulsed by it. Data tells you something, but there are things you still don’t know. So we invite other people to look and listen and think and experience that uncertainty.

HORVITZ Data creates a lot of absences.I did a project in 2007 called I will think about you for one minute. I’d send the person two emails, one when I started and one when I stopped. The timestamps of the emails would mark the length of the minute. The email was the work, but the project was also about changing the direction of the attention economy: I’m going to think about you instead.

M. OBADIKE And I’m gonna prove it! I love that. I feel like there’s so much to it. How do you know when somebody’s thinking about you? And then there’s the question of form. I wouldn’t say I experience the timestamps as material, but they enable me to perceive something immaterial. They offer a form for perceiving this thing that doesn’t have a material presence.

HORVITZ I was calling it a residue.

K. OBADIKE I love pieces that have this two-sided nature. What I love about your piece is that it implies real intimacy: I’m going to think about you for a minute. Yet it’s so incredibly distant. It’s so hilarious and so serious.

M. OBADIKE Do you think about it as an internet work?

HORVITZ I don’t really think about it that way. I mean, yes, because it uses the internet but also, no, it’s conceptual art—just words and thoughts. The internet makes it more accessible, more available. I don’t know how else to say it. It’s enabled by the internet, maybe.

K. OBADIKE The timestamps make it available, like an entry in a log.

HORVITZ Sometimes I’ll go to someone’s house and see the emails framed on the wall—whoa.

M. OBADIKE There’s something interesting about printing things from the internet.

HORVITZ Yeah, I love printing.

K. OBADIKE That was a special time in the early days of the internet when people would find things that were important and print them out on paper. What do we do with things that we find fascinating or curious or moving on the internet now? How do you hold on to those things?

HORVITZ Take a screenshot.

M. OBADIKE Exactly.

HORVITZ Then what do you do with the screenshot?

M. OBADIKE Nothing. Or you print it in a book of photos.

K. OBADIKE I think a lot of the stuff that we have done with data is about trying to make information visceral, to give people a way to feel it. The last few years of dealing with more and more data taught us that having a lot of data doesn’t mean we know any more. So what do we do with it? I think part of what we do as artists is help people feel different kinds of data, help people have an emotional engagement, so they can laugh or feel deep confusion.

M. OBADIKE Having more data makes it harder for us to have feelings. The more data we have, the less we feel like we know unless there’s an environment built around it to help us engage with it.

K. OBADIKE Yeah, the work is about creating a context where that can happen. Artists are always taking the scraps and the junk and then showing you how you can feel something about this thing that you might have thought was worthless. A lot of the data dumps from official institutions are about making data points somewhat homogenized even as we see variables. In the physical world, we understand nuance and texture and taste. Our work is in part about bringing some of that nuance back to points of data.

—Moderated by Brian Droitcour