Libby Heaney & Sarah Shin

How can the empirical fields of science and technology be reimagined to reflect a more mysterious reality? Might quantum physics offer a useful framework?

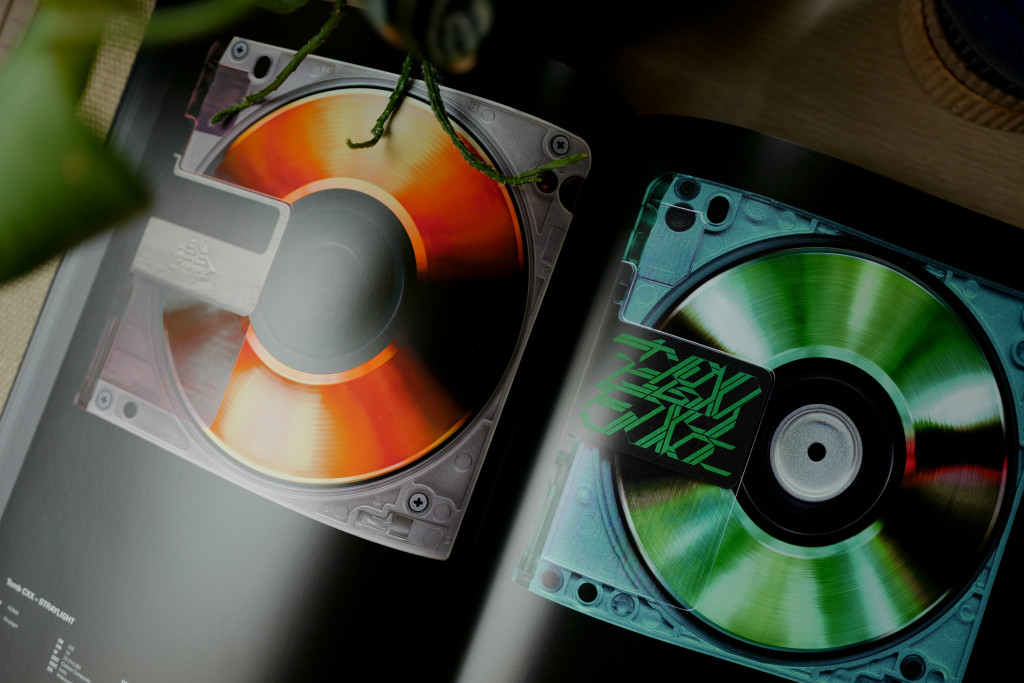

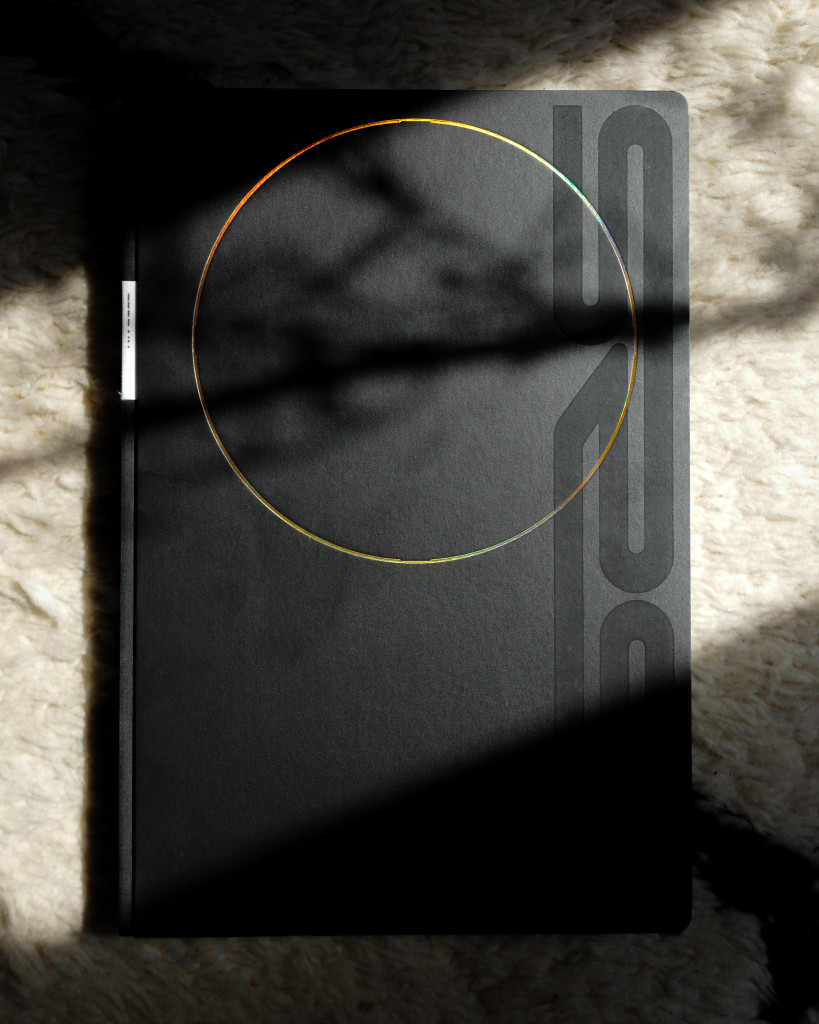

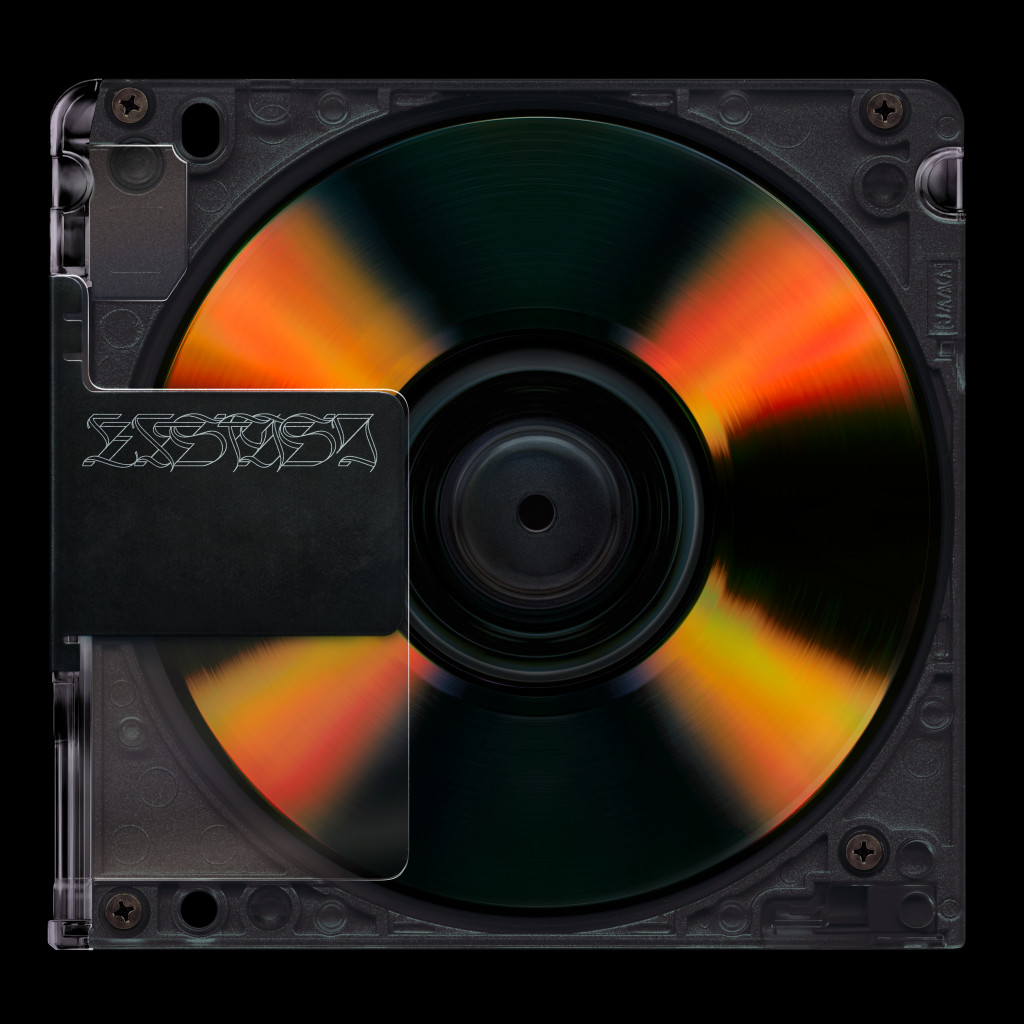

Both David Rudnick and Metahaven practice a kind of expanded graphic design, extending theories of visual organization to social, cultural, and political issues. The work of Metahaven, a collaboration of Vinca Kruk and Daniel van der Velden, spans design, film, and writing. Their recent video essay Chaos Theory (2021) explores relationship dynamics between parents and children through multi-voice narration. It is presented as an installation that includes woven textiles designed by the artists. Rudnick’s Tomb Series (2021–) is a multifaceted web3 project with an emphasis on physical media. It consists of 177 unique works that appear both as digital objects and in the hardcover book Tomb Index, overlapping in a meditation on emerging value systems and immaterial ownership. The project builds on Rudnick’s MFA thesis project, which was advised in part by van der Velden. In the conversation below, van der Velden speaks on behalf of Metahaven with Rudnick about how emergent forms of social organization are manifesting in digital and physical environments, and the ramifications of these shifts for the work of designers.

METAHAVEN Objects of graphic design can serve as a compounded narration of the time in which they were made—they reflect things from the much larger environment that they exist within. I’m curious about your Tomb Series and how it relates to your practice as a graphic designer, as well as how you think value is circulating that project and comparable forms of serialized digital objects, like NFTs and governance tokens.

DAVID RUDNICK The core of my MFA thesis from 2016 could be condensed into a single sentence. My assessment was that the transition from the medium that was known as graphic design in the twentieth century to the current visual milieu could be summed up as a transition from a system of grids to what I refer to as a system of overlays.

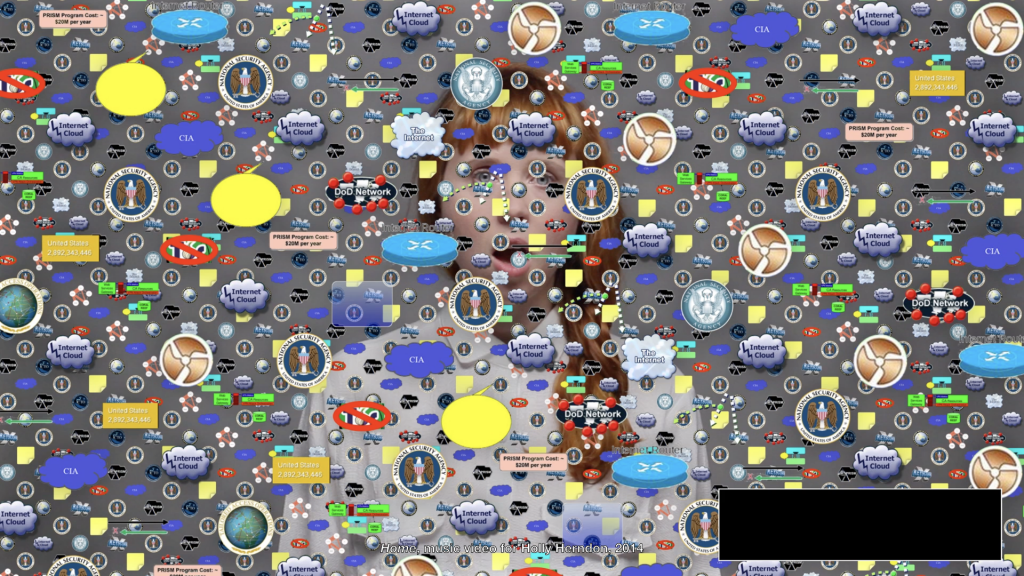

A system of grids is a prognostic, social, pre-fact practice of designing, and is also a practice of envisioning and orienting systems of information and data into preordained, geometric, or rectilinear systems that then stay concrete. They accrued strength through their consistency and through the application of art, social activity, capital, and data through the system. But we were emerging into a reality where the systems of visual application and social design had become reactive and responsive. This was collapsing the social space of action to the observer and what they could apply on top of either the physical world in a kind of AI/AR overlay matrix, or within digital realms that they could reorient, or apply filters to reshape and reflect their experiences.

We don’t have a word for this overlay system. It’s not modernity, and it’s not postmodernity, which consisted of rearrangements within the grid. Our built environment as well as the digital realm in which we find ourselves on a day to day basis, in addition to our movements on a macro level—socially, digitally, and politically—continue to push us further into the overlay system, and into a world where our tools are that of superimposition. These tools emerge from the observer and may not be objective. It is unique and peculiar to the individual, not a kind of designed map that’s available to all observers.

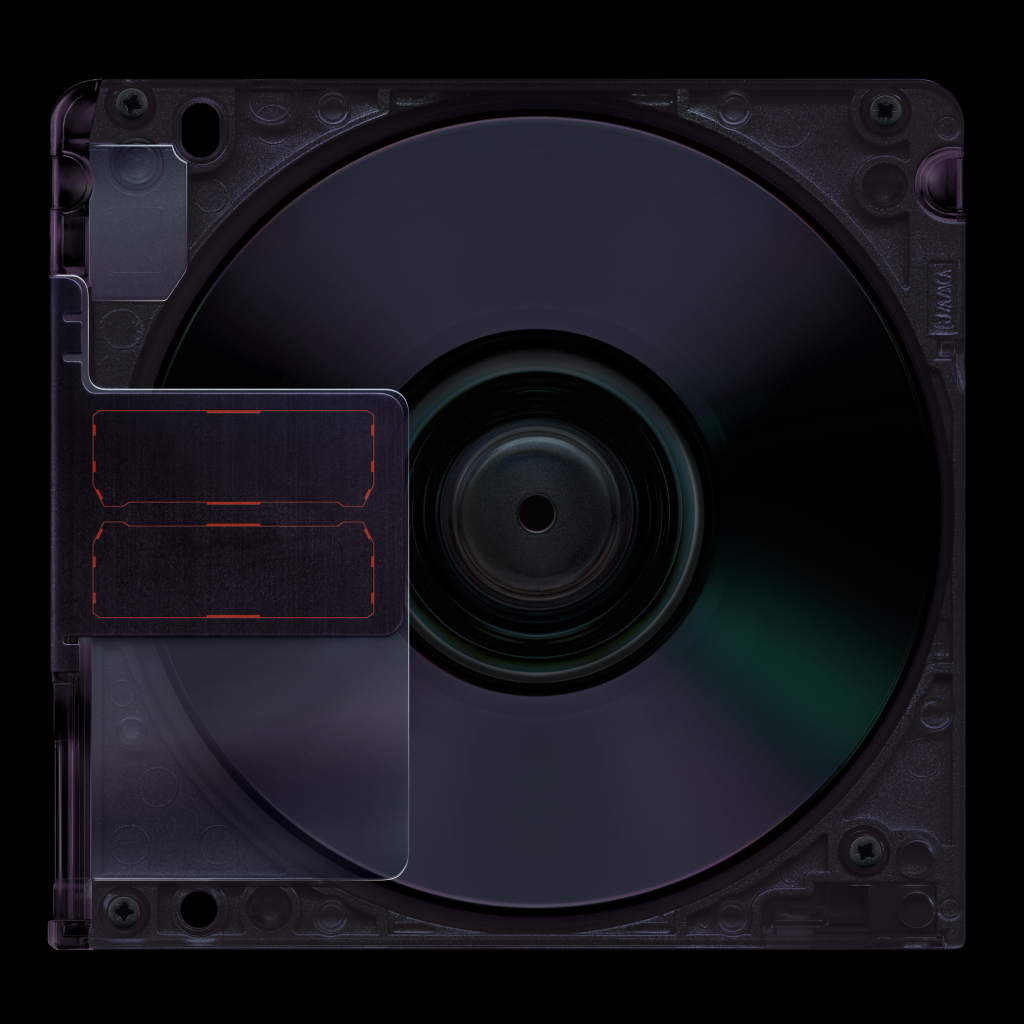

The value systems of the future may have to confirm, contort, and respond to the ways in which individuals receive speculative and reactive value. The Tomb Series is a body of work that I think makes quite concrete the relationship between the ruins of a recognizable interworld between subjects and a set of functions that can be applied to them, be they mechanical or activated by digital structures, like blockchain or contracts. They can also be activated by poetic or emotional things, like their names. This is one of the things I like about making work on-chain: it can be both interpretable and protected from fragmentation.

METAHAVEN Metahaven’s practice started in 2004 with a project for a self-declared nation in the North Sea created in the 1960s, the Principality of Sealand. During the dotcom boom of the early 2000s, it became a short-lived data haven, meaning that it was a physical storage space for information that would exist outside of the jurisdiction of governments. It had a libertarian streak.

We saw this as a research case, and we created a completely online, jpeg-based visual identity for Sealand. It claimed that the physical objects tied to sovereignty no longer needed to exist physically in order to be valid as signs that demarcate identity and positionality. In turn, these jpegs were reproduced through, and gathered their legitimacy through, Google search operations. This meant that anything linked to Sealand in even slightly oblique ways—and that could go as far as someone tangentially related to the murder of Gianni Versace, whose killer was carrying a Sealand passport—became part of a universe of links and references. The idea of the search links all of these things together and creates identity.

What I want to say in response to your story about the Tomb Series is about fiction, storytelling, and also about simulation. These new NFT series are reminiscent of serialized fiction. For example, there’s a children’s book series called Warrior Cats, which is like Game of Thrones but with cats. It’s a potentially endless series of iterative fictions about clans of cats, and the covers are all different cat faces with glowing eyes printed in high gloss. So there’s always the same visual formula behind them. The characters in the series number in the hundreds. They’re almost uncountable.

This is similar to how you described web3 from your perspective. What you gave as the premise coming from your thesis work, leading up to the Tomb Series, exists by intense narration, by an intensely projected theory of the world. There are artists that just throw objects into the world without explaining the philosophy behind why they exist. When you describe the Tomb Series, I am intrigued, but also fascinated by the narrative intentionality that seems to be there.

RUDNICK You said that the number of Warrior Cats was “almost uncountable.” That’s a phrase that I often return to when talking about the value of web3 projects, and a factor you can apply to some of the core constraints of the Tomb Series. When looking at some NFT projects, the astronomical number of objects in a series seems to be decided on a whim, somewhere between total caprice and greed. The creators are asking how many they need to make to generate enough money, but also enough to reliably produce interest, diversity, or structured rarity. I had no interest in conceiving of a series in that fashion, and all the works in Tomb Series are titled and composed in advance. They’re not generated at mint. The number of them—177—is a somewhat arbitrary figure that felt like the right amount in my head, and the number at which I could generate different named positions myself without relaying a sense of exhaustion to the viewer.

When I arrived at 177—and this is where the macro political idea of how these things relate to real world structures comes in—I immediately starting moving towards other structural elements because I felt that there would be some degree of self-organization thematically, and that people would want to project hierarchy. Maybe viewers would identify themselves more with certain bodies, or they would see similarities or differences within them. That’s when I created the concept of the eight “houses” that the different Tombs are sorted into. Yes, one could draw analogies to narrative, but I also think there is another component that is purely structural. How do we approach a collection of things as human beings, and how do we create value? One can choose to approach an NFT project as producing a token that is a different way for an individual to accrue wealth. But I think that where you see narrative or storytelling, I see a privileging of a system of a different type of value.

METAHAVEN There are all of these developments in the world that are all in some way related. There is the crisis situation with energy, which is precipitated by Russia’s war in Ukraine. There is a shortage of airline staff, resulting from neoliberal systems of flexible contracting (among other things), that causes people to miss flights and lose their luggage. There are the ways in which digital currencies rely on the energy grid, on some form of common resource, which is entwined with geopolitics and other layers that sustain the system. It’s interesting that the system that came after the grid is actually extremely patchy, and extremely entangled. “Entanglement” is a word that is used so often that I use it with caution, but I think it speaks to the way these systems feel to us. Those feelings have been key to what Metahaven has been doing in our use of moving images.

Right now, we’re making a film called Capture, which is focused on the compatibility, or incompatibility, of art and science. Our protagonist is winding a story around a series of videos that belong to the CERN particle colliders—a historical body of film footage that covers how CERN developed its colliders since the 1950s to go after fundamental particles. One question that’s always key to us is how the subjective narration of these realities feel and show how the story isn’t totally capturable from the purview of a single systemic, or indeed scientific, viewpoint. However, what we’re interested in capturing is the idea of the overlooked, the idea that there are always people and entities that are not seen by a system that claims to be universal.

When we talk about web3, and the ways in which it may develop, I feel convinced that it has not yet reached anything close to resembling a final form. For example, what is the value of labor that is informal, that is not covered by a DAO, or not covered by agreements, contracts, or formalization through code? There are some groups of people whose labor cannot be tokenized because they lack the interest, the access, or the means of registering themselves in this type of post-grid structure.

There are also restrictions of data in web3 that come to mind. There’s an interesting notion of storage limits within web3, or NFTs specifically. There are similar restrictions in the moving image when Netflix streams in 4K. We were told that Netflix actually has contractual clauses in place about the percentage of shots in a production that can be handheld, because a handheld shot means more data. There’s a storage and transmission component to that in the 4K regimen that leads to cost. Of course, such a restriction may have consequences for how something feels or appears.

RUDNICK To return to your idea of the overloads, or the unseen, and as well to the idea of the future of web3, imagine that fifty years from now we no longer have the privilege of being able to look at the world and focus on the parts of it that are not the catastrophe, because perhaps at that point everything is the catastrophe. The accumulation of these actions has reached the point where it’s unmistakable that we are surrounded by the legacy of our folly, and of our mistakes, and of the things that we had overcommitted to and in turn destroyed some of the things that we had taken for granted. I would imagine even more that this has been an important tenet of the conversation about NFTs over the past eighteen months. Wanton consumption, and massively wasteful lossy processes, will not be viewed particularly fondly, to put it mildly.

You are right to point out the hybrid nature of Tomb Series. The marriage between an on-chain structure, a series of digital hyperobjects, and a physical index can expose the weaknesses in the different nodes of our current system. Imagine a point in the future, where perhaps the chains have collapsed, and the ability to access the digital realm is not as ubiquitous as it is today. I am proud to engineer a project where one could open a book with zero power consumption, and read, look, and think about the fundamentals of what was built in this project, and then imagine what the rest of it may have been. We have agency working within overlooked structures, technologically less refined structures—which, from a power consumption perspective are unbelievably sophisticated structures. The form I keep coming back to is language, and specifically poetry.

I want to ask you about your weavings and tapestries, and their relationship to grids and matrices, as well as the formal codifications of data.

METAHAVEN I completely share that sentiment about poetry. It’s useful to point to the materiality of poems when we talk about materiality in art in general. For us, working with textiles was a way to let go of the control that we have when we’re designing in a purely digital space. When we began to design environments for our films, such as tufted carpets that you could sit on while watching, we started to become more and more interested in the ruggedness and imperfection present in textiles in spite of their obvious relationship to code. You can predict them, but there’s still a sense of surprise. It’s the same for moving images, when you’re working with actors and scenery in the world. It’s the opposite of a 3D rendering because you’re working with massive entropy that you can’t control. Textiles became a way for us to express ourselves essentially as a form of film stills. A woven object is an intensely more physicalized object than a printed page or digital image.

We just made works for a two-part series, Living Together in Stories, which were woven on a machine. It feels like a really natural platform for us after making work that was more “digital looking,” to make things slightly lower res. The fact that these are objects people can potentially have in their home creates a sense of intimacy with a viewer. It’s not unlike poetry. Another reason we began working this way is that at some point we felt that people assumed all our work was large by default.

RUDNICK The preciousness of scale also comes into play, and we began to discuss this when we were talking about the rugs and their potential importance as domestic objects. I feel the same way about books—that they’re aspects of private, personal space. This creates tension, or a conflict with the screen and the digital realm that is home to so much of our lives. We as a society have moved away from the “modern project,” Le Corbusier’s idea of the “house as a machine for living,” as well as the late twentieth century’s production of design objects that were designed to create environments that reflected our hopes, dreams, thoughts, and feelings. That whole aspect of the design industry has ceased to exist to a certain degree. When I think about contemporary design objects, I think about things like the ring light or the Philips Hue lightbulb, which allow you to turn your home into a well-lit streaming platform. These are objects that curate your digital space. It’s a utilization of the home as an accoutrement to the digital, rather than ias an emotional realm where our ideas of self and the world might be manifest.

Your textiles are really a challenge to the screen because they’re matrix-based. They present a different kind of screen that has an identifiable grid of real estate through which its communications are made. You can identify the individual tufts and tools by which the composition becomes a body of language and ideas.

In the weaving Transfer Entropy (g’s world), there are amazing suggestions of the movements of birds. In the “Tomb Index,” a text I wrote in 2013, I was trying to process different organizational logics that seem to be superimposing on top of one another. I wrote about how people were ordained into a line at Berghain, and how that contrasted with the interaction of bodies on the dance floor, moving in packs in response to the music. It reflected the iterative structures of religion, and how different congregations would form around central texts. I also wrote about the murmuration of the bird flocks that you’d observe walking out of the club and into the daylight at five, seven, eleven in the morning—they would move to their own rhythms and pulses. This applied to the organizational structures that were emerging with the blockchain at the time as well, these superstructures that were emerging from the visible organization of lots and masses.

How we see ourselves among this disassembling of modernity, and the removal of structures that once held space together will define a great part of how we make our way through the coming years. I think these movements—the flocks, the dances, the coming together and coming apart—are such a powerful, poetic factory in a moment where we don’t yet have the words or control interfaces to define them as anything other than inflows and outflows.

You see these murmations in web3, too, in the form of rushes into projects and rushes out. It’s funny that you used the word “rugged” when describing the texture and material of textiles, given the connotation of the word “rugging” in NFTs—the revealing of a project as a scam. In the collapse of the artifice when an audience is rugged, the poetry is gone. All that remains is the dust of whatever was there.

—Moderated by Lauren Studebaker