Rare Scrilla & Pepenardo

Two artists talk about the Fake Rares community, how it maintains and updates the legacy of Rare Pepes, and the future of art on Bitcoin

The NFT market has brought attention and money to creative coding, once seen more as a hobbyist activity than a path to a viable art career. In addition to creating new ways of collecting generative art, the blockchain also offers some new ways to make it. The small, cohesive body of work released in the last year by the artist known as DEAFBEEF is entirely on-chain, meaning the code that generates his monochromatic audiovisual compositions is contained within the NFT that the collector purchases; in some of his series, the owners of the NFTs gain permission to change the code and modify the work. Over her twenty-five year career LIA has experimented with generative processes in every medium imaginable, from interactive websites and live concert visuals to plotter drawings and 3D printed sculptures. She recently released her first on-chain project through the Art Blocks platform. DEAFBEEF and LIA met to talk about what their seemingly disparate practices have in common, as well as the misconceptions held by many who are encountering generative art for the first time.

DEAFBEEF As someone who has been making generative art for a long time, I’m curious how you feel about all the recent hype and speculation around it.

LIA I was surprised. I asked myself why it’s happening. I think it has to do with Covid: everyone has been forced to move online, so the digital stuff becomes more real. Young artists are getting more attention than the old ones. It’s the curse of the pioneers. By the time the next generation comes around, people already have some familiarity with what they’re doing and can acknowledge their work more easily. Artists in the first generation of generative art, like Vera Molnar or Manfred Mohr, did not get any attention until an essay by Casey Reas published in The Anthology of Computer Art: Sonic Acts XI.” in 2006. That’s where I first heard of them.

DEAFBEEF I’ve learned that there are many threads of generative art. It’s not one lineage. It’s been interesting to piece things together and hear about everyone’s different experiences.

LIA What I’m seeing now is a lot of art that is not really art. People are just taking the formulas and choosing some colors and that’s it. There’s a wonderful list of generative formulas compiled by Taru Muhonen and Raphaël de Courville. I call it the List of No Excuses. If you know that list, you can better judge generative art. You can tell how much artistic input there is. I’m not saying artists can’t use those formulas, but they should add enough to make it their own. Tyler Hobbs wrote an article about what he used to make Fidenza, and it’s based on flow fields—algorithms that mimic the motion of liquids and gases. I was in a bad state in 2018. I didn’t have much income and my work didn’t seem to be getting much attention. So I decided to do something really basic with flow fields. I used the colors from Van Gogh’s Starry Night for the palette, because the shapes of flow fields remind of that painting. And I sold the work. I can do easy art without much input, too! But it wouldn’t make me happy in the long term.

DEAFBEEF There’s an interesting intersection of hype and money around generative art. The collectors coming to NFTs from decentralized finance are often only seeing generative art for the first time. They think it’s cool, but they don’t have very much context. They think it’s new and exciting. As someone who came to the NFT space very recently, I think about the wide variety of generative work that came before that. Where does it fit in? People don’t know about it and we should show them.

LIA I should say that working for a long time in the field doesn’t automatically make you good. Someone can create bad work for years. And there are some new artists whose work I really like, such as IX Shells, who is quite young. I love her work. But I know all these formulas, so if I see a work that uses flow fields I’ll recognize it as such. And as people see more work, they’ll say: “Hey, this looks like a Fidenza.” If everyone uses a flow field, it’s not artistically interesting.

DEAFBEEF A lot of the generative art that sells well is seen as painting. People can understand it because it looks like an art object as traditionally understood. And maybe it resembles abstract expressionism or something else they’re already familiar with. And that’s why it does well, but we have to remember that commodity value is often independent of artistic quality, and that there are many other generative art formats to explore. By the way, I don’t mean this to be negative. I admire Tyler’s work. And I understand he doesn’t control how his work is received.

LIA His work is very good. I think Fidenza is great, he added enough to make it his own. But I’m not so interested in exploring formulas. When I started I’d look at programs to see what formulas others were using and see what I could do with them myself. But later I tried to make work that reproduced patterns in nature. In 2018–19 I made work about the four seasons. In spring, for instance, there are fresh flowers and everything is colorful. I tried to translate that principle into shapes and forms. In winter everything is black and white, and nothing moves much, as if it’s frozen, and the autumn piece has leaflike structures in brown and red. That’s more interesting to me—to have something I want to show. Some of the works I see are appealing, like eye candy, but I’m having a hard time understanding why people are doing it. It seems more like a study, an experiment to see if the formula works, than an attempt to express something.

DEAFBEEF Right now we have an image-forward market. Over time it will mature, and there will have to be more to the artwork than what we’re seeing in some cases now. You’ve described your work as “making machines.” I also think of designing a system as the artwork. The system could be a process or it could be a class of outputs. For your Art Blocks project you made a system that can generate a class of outputs that are within bounds that you’ve designed. So it produces these external objects. But I still think of the system as the artwork. I’ve talked about scrawling directly onto the digital medium and that being my artwork. I tend to work at a low level, working with raw numerics, but I’m still writing systems to manipulate those things.

LIA I don’t know if you’ve looked at the rarities on my Art Blocks project, but I have one number that’s labeled “tested in LIA Labs.” That’s my joke. Because sometimes the process gets down to tweaking the numbers that define the parameters—of rotation, size, speed, transparency. I think that’s the artistic part. I don’t know why 0.3016 works as a number, but it does! I think of it like ballet dancers on a stage. They move in the same way, but each one is different. If they were identical, it wouldn’t be beautiful. A specific number can create the right amount of variation. If it’s too little, or too much, it won’t look good.

DEAFBEEF When I talk to artists I often hear about that spectrum. Too much variation is just noise. No variation is boring. In between somewhere is a sweet spot and that’s what a lot of generative art seems to be navigating. And the great thing about generative art is that you can leverage the system to add that noise using randomness, whereas it would take too long to do it manually. As the artist you’re leveraging the computation to do all that while inserting yourself in a feedback loop to judge the aesthetic outputs and tweak the algorithm to get them where you want them.

There’s a misconception that generative art is about designing a system that runs automatically, which leaves people wondering what the artist actually does. But when you’re in the process of designing the system you’re in that feedback loop making decisions. It’s a unique kind of conversation between a machine and a human.

Sometimes when I’m communicating this to a layperson I say it’s like turning knobs on your stereo, to adjust the volume, or the levels of treble and bass. You’re tweaking things. In systems language, these are inputs. Different inputs correspond to parameters. While exploring, an artist might fix those inputs and capture the result, whereas in an interactive work those inputs might change in real time as the system is working.

I’ve made a deliberate decision not to make interactive work right now, so I don’t have to depend on particular libraries or hardware. Real-time interactive systems are more complex. My goal was to make it simpler for myself because my time is often fragmented. I want to make sound and monochrome animations that are pre-rendered, so I can use very basic tools. It’s probably quite different from the way you work.

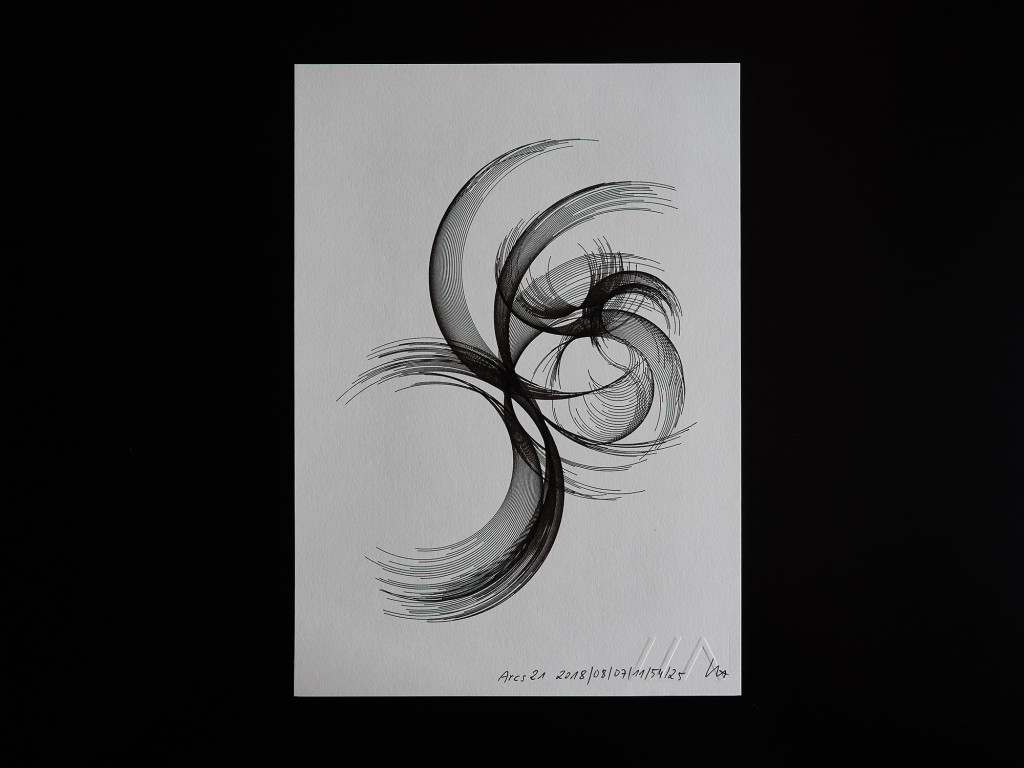

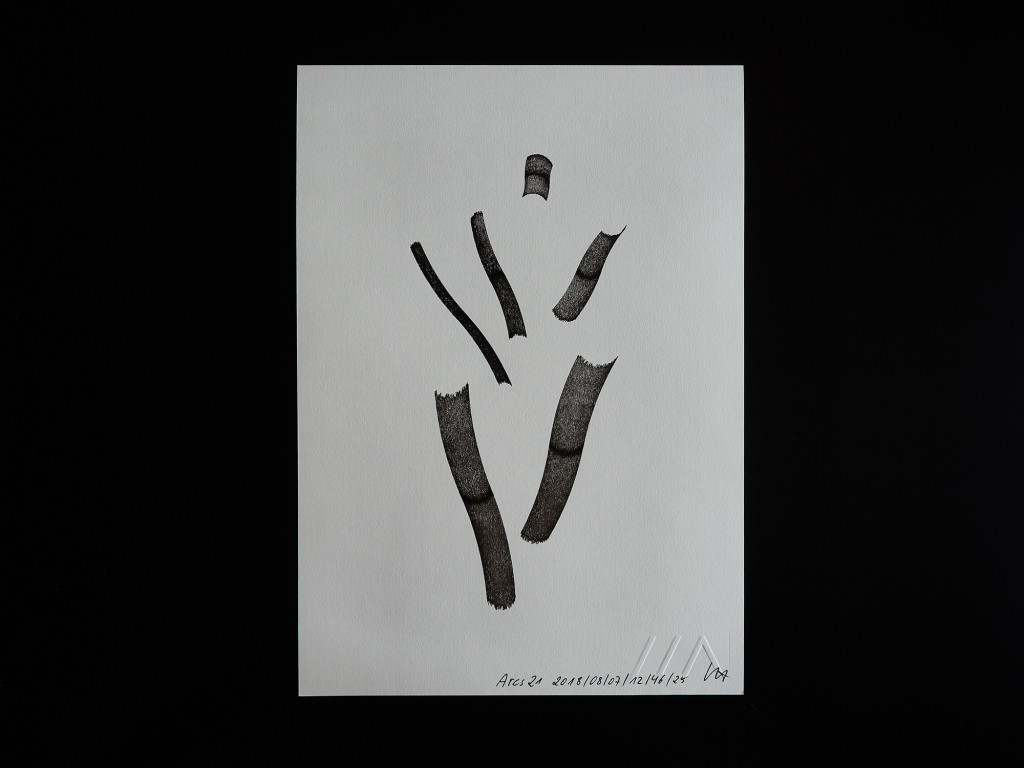

LIA I don’t think our work is so different. A lot of my stuff was monochrome when I started. The interesting part about interactivity for me was that people would always use it in ways I didn’t expect. In the last twenty-five years I’ve done so many different things. It’s hard to pin my process down. What I like to do is abuse a system, or hack a system. I borrowed a plotter to make drawings and I thought it was boring. If I’m just using it to output something that’s on a computer I could use a printer. So then I figured out how to hack the thing and move the pen up and down, and then I inserted a brush. I use a tool as long as it’s interesting and then I get bored and move on to something else.

DEAFBEEF I can certainly identify with that. And many other generative artists would say the same. Because the goal is to find something interesting to tinker with. And the exploratory process of that, at least for me, is the motivating factor. And I think a lot of people feel the same way. You’re looking for the same thing that someone else might find when seeing an artwork for the first time. You want to surprise yourself with your system.

You could say generative art goes back millennia. Every culture makes patterns according to formal rules, in textiles in beads. There are sacred geometries. The music of the ancient Greeks was based on the movement of the planets. But if we’re talking about technology of the last hundred years, then sound technology is much simpler than anything visual. It’s just one signal. It’s a voltage that goes up and down. And you can process that much more easily than a video signal. So there are connections between music and generative art, sometimes it’s been a precursor. I recently learned that Vera Molnar was friends with composers like Michel Philippot, a serialist who wrote using the twelve-tone technique. It was through the influence of serialist composers that she began using aleatoric methods in her work. She was already doing the constructivism-inspired work, but she got the idea to use dice to incorporate randomness before she started using computers. Manfred Mohr was influenced by the same composers. He knew Pierre Barbaud, who was friends with Molnar as well.

LIA In the eighteenth-century composers used dice games to write music. A schema for one such game was attributed to Mozart.

DEAFBEEF It’s not that there’s a lineage from music to generative art, but there are cases where they did connect. For me, the paradigm of a system with inputs and outputs maps perfectly with electronic synthesizers.

LIA When I started with generative art I made works with sound. My first programming language was Lingo and I used Macromedia Director, which was normally used for making CD-ROMs. It’s funny—my early works all have sound, but when I started showing at museums it became a problem. They’d use headphones, and only one person could listen at a time. I think that’s one of the reasons why I stopped making sound pieces.

DEAFBEEF Yes, sound is at a disadvantage. Social media is also visually dominated. I don’t think you can even share just a sound piece on Twitter. There has to be some kind of visual placeholder.

LIA That speaks to a bigger problem: there are platforms that define what you as an artist can do. I could only put generative art on Hic et Nunc because they were the experimental guys. I can’t put it on Foundation or SuperRare or anywhere else. The platform Art Blocks allows generative art that uses the token hash as input—if you press A when looking at one of my works there you can see an animation. SuperRare and Foundation have a 40 MB limit. That’s nothing if you want to make a really nice video. I put two on SuperRare and they are quite small, under a minute long. That’s not really what I want to show, but I’m restricted there, everyone is. I can make the same amount of money with a picture, and it’s less work. So at the moment this is driving me to make pictures only.

Tyler Hobbs started calling the kind of work on Art Blocks “long-form generative art,” and said few artists can balance consistency and unity across a thousand outputs. Everyone took up this idea as if it’s natural.

DEAFBEEF It appears to create a hierarchy, which wasn’t his intent. He’s just describing one form of generative art. But the exposure that it made that way of thinking seem pervasive.

LIA He’s saying that on Art Blocks all the outputs have to look good. When I’m making a work, I get the outputs and select the ones I like best. That’s a whole process, which I think is also artistic.

DEAFBEEF Yes, of course!

LIA I have twenty-five years of practice looking at folders with hundreds of images and making selections. I make a new folder called SEL, for “selection,” and select the first batch, then I have another folder called SEL SEL, then I have a third one. There are three steps to get the ones I like best. I don’t know if they’re the best images but they’re the ones I like.

DEAFBEEF That’s the part that the human brain brings to this feedback loop.

LIA I’m looking for something interesting. It’s hard to describe. You can’t say that straight lines are good and round ones are bad. It’s about the proportions.

DEAFBEEF Max Bense and others in the 1960s and ‘70s somewhat naively tried to write rules about what is good aesthetically. And that played a big role in the early constructivist kind of generative art. But ultimately you can’t rely that heavily on formalism. Perceptual and contextual judgements are needed.

LIA I’ve watched a lot of food photography videos for my blog. They have a lot of rules. The spoon has to go at a certain angle. If you put berries on something, there should be an odd number of them if there are fewer than seven, but if there are more than seven it doesn’t matter.

DEAFBEEF Food photography is long-form generative art! Roll dice within those parameters and you’ll always get the perfect food photograph. In making your Art Blocks project, you still had to make those selections. You still went through thousands of outputs and then constrained your inputs so they mapped onto that set. It’s not really that much different when you think about it. People mythologize the idea that one program can produce so much variation. But systems are composable. You can always take two or more programs that have different kinds of outputs and put them into one program that selects between them. Mathematically, there’s no difference between “multiple programs” and a single one that performs a selection between a set of parameters . At the most basic level it’s all the same: it’s a system that has a generative part and a human in the loop who makes some type of selection. Whatever paradigm you subscribe to—whether the work is interactive, whether you present one output or all of them—is secondary. Now some of the selection has gone to the market and the collectors, who value attributes that show up infrequently in the outputs. The rarity thing is strange, and says a lot about social psychology.

LIA It’s not something I was looking for when I was selecting.

DEAFBEEF If you wanted it to be rare, you could make it rare.

LIA When you’re writing the program and find a nice accident, you figure out how to repeat it. With my Art Blocks project I built in some rarities. I played the game. I don’t think the rare ones are the most beautiful. They might even be uglier than the rest. But they’re rare. I personally wouldn’t pay more for something because it was rare. This way of thinking turns art into Pokemon cards.

DEAFBEEF Yup, collectability. I like thinking about all these concepts. It’s interesting conceptually, and an artwork could comment on how this is happening on such a huge and intense scale. Rarity is arbitrary. The artwork is the system.

LIA There’s not enough critical discussion in our field. I’ve stopped going to Ars Electronica. There would always be one or two good pieces. The rest was crap. And there was no critique. Everyone just patted each other on the back. The focus was on new technology. When Kinect appeared everyone was making work with it. And I wondered: Did you really want to make that? Were you really waiting twenty years for Microsoft to put that on the shelf so you can finally do what you’ve always wanted? There’s no critique in generative art. I live in Vienna. Austrians are moaning all the time. It’s an art form, especially in Vienna, to say how shit everything is. I have a hard time with Americans because you always have to be happy. The fact that generative art all happens online now means it’s happening on Twitter and Facebook and other social media platforms, which are all American. I’m not saying that Americans are unable to have critique. But it’s not happening. I would love to have someone tell me my work is not good enough, that I should have changed this or tried that.

DEAFBEEF For a lot of people creative coding was a hobby. When they showed their stuff to their friends on social media, they weren’t looking for tough criticism. But if it’s being presented as art and collected at high prices and interacting with the wider art world, then there must be critical discourse. And I look forward to participating in that.

—Moderated by Brian Droitcour