Glitch, Body, Anti-Body

Legacy Russell’s feminist theory of the glitch yields insights into how social and technological systems of control can be disrupted by the art and lives of queer and trans people of color.

On the NFT marketplace Nifty Gateway, a single Ethereum wallet is the origin of works by many different artists. The wallet an NFT is minted to is the seed of the artwork’s history of ownership. While a shared wallet may seem innocuous, even collaborative, it masks the origin of the work. At its core, an NFT functions as a certificate of authenticity that confers verifiable digital provenance. More generally, the blockchain promises a time-stamped record of a chain of ownership going all the way back to the artist. But if this record does not begin at the work’s origin, the NFT is merely a receipt of past transfers, not a certificate of authenticity. Using a shared wallet is like adding a group signature to a painting made by one artist. It forever makes our knowledge of the artwork’s origin approximate.

When artist Joanie Lemercier learned that the works he was selling on Nifty Gateway were being routed through a shared wallet, he declared all his NFTs on that platform “null and void” and offered his collectors a free replacement that was minted from his own wallet on a different blockchain. He explained his reasoning in a post to his blog. The volatility of the NFT market already poses a challenge to appraisers, whose job is to ascertain the value of works of art; according to a report from UBS and Art Basel, the NFT market for art and collectibles grew from $4.6 million in 2019 to $11.1 billion in 2022. Appraisers face additional challenges due to the structural nature of this rapidly evolving technology, alongside the complexities presented by swift market growth. Lemercier’s story encapsulates an under-discussed truth: there are no established standards for NFTs. The development of best practices requires input from not only appraisers and art market entrepreneurs, but from artists, attorneys, technologists, and an unlikely source of important expertise: time-based media art (TBMA) conservators.

Over the last three decades, media art experts working in museums have developed principles for the conservation of time-based works. Projects like the Guggenheim Museum’s Conserving Computer-Based Art Initiative and the Variable Media Initiative, also instigated at the Guggenheim, established protocols recommending that conservators interview artists about their processes and document their choices of software and hardware, so that future decisions about display and preservation can be made with the most complete understanding possible of the artist’s intent. The conservation of computer-based art therefore involves what might be described as an audit function—an assessment that is made far from the intent to sell and thus is objectively focused on the artist’s point of view and the steps involved in the technological construction of the piece. While conservators and their expertise are rarely involved in the appraisal process, it is in fact their separation from the market that offers a useful model for approaching the appraisal of digital art. In particular, appraisers can learn from time-based media art conservation’s set of forensic best practices for understanding digital work from the artist’s studio to the museum environment.

While conservators and their expertise are rarely involved in the appraisal process, it is in fact their separation from the market that offers a useful model for approaching the appraisal of digital art.

Conservators have developed their approaches across an exceptionally wide array of artworks. Groups working to develop NFT appraisal standards will need to embrace the complexity, variety, and mutability of works inhabiting the NFT space. Conservators not only approach every artwork individually but synthesize into their process the working practices and intentions of a wide variety of actors, including artists, curators, collectors, and viewers.

While “digital tokens” were included in the 2020–21 edition of the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) guidelines, the standards don’t reflect the nuances of digital art, largely due to the lack of a developed market for such works. The guidelines used by art appraisers are based in the practice of valuing personal property, adapted from real estate. Appraisal encompasses many factors, including the artistic merit of the work as well as its authenticity and condition. Appraised values also vary depending on the purpose: appraisers intentionally arrive at different valuations depending on the aims of the appraisal—tax deduction for donation (fair market value), insurance (retail replacement value), or equitable distribution of assets, e.g. in a divorce (marketable cash value).

In doing their due diligence, appraisers most frequently use a “market data” methodology in which they gather recent sales records for similar works and then rely on these comparables, or comps, which are chosen carefully from sales by auction houses and private dealers. The market data approach is then modulated depending on the condition of the artwork relative to comps. While these forms of value are in shades of gray, the more binary question underlying this analysis is that of authenticity: Is the work real? Was it made by the attributed artist? Can that be proven? While appraisers do not generally vouch for authenticity of works, the work’s authenticity is a prerequisite for the appraiser’s overall analysis.

This is why shared wallets pose a significant problem. How do we know Lemercier made the work attributed to him if it is minted from the same wallet as works by many other artists? An appraiser would have to trust Nifty Gateway rather than relying on the decentralized ledger of blockchain. The shared wallet creates a “studio of Nifty Gateway” provenance, which blurs information in a way that forever compromises the precision of the analysis.

The shared wallet problem also raises two other key questions: First, how much technological expertise do appraisers need in order to comprehend the problem in the first place? Does an appraiser need to be literate in the programming languages used in smart contracts, for instance? Second, how can we create digital provenance otherwise? These questions are unusually well suited to a group of people whose expertise has been increasingly established since the 1990s but who are still often distant from markets: time-based media art conservators. The methods developed in TBMA to understand the entire construction of the work of digital art can be combined with the time-stamping functions of the blockchain itself to ensure authenticity and to track valuation, especially when it comes to the real complexities of works that must be ported over from dormant blockchains and reminted, which is likely to be an increasingly common situation. TBMA has established practices of surgery or autopsy of an artwork that can inform an appraisal’s records linking the work to the blockchain.

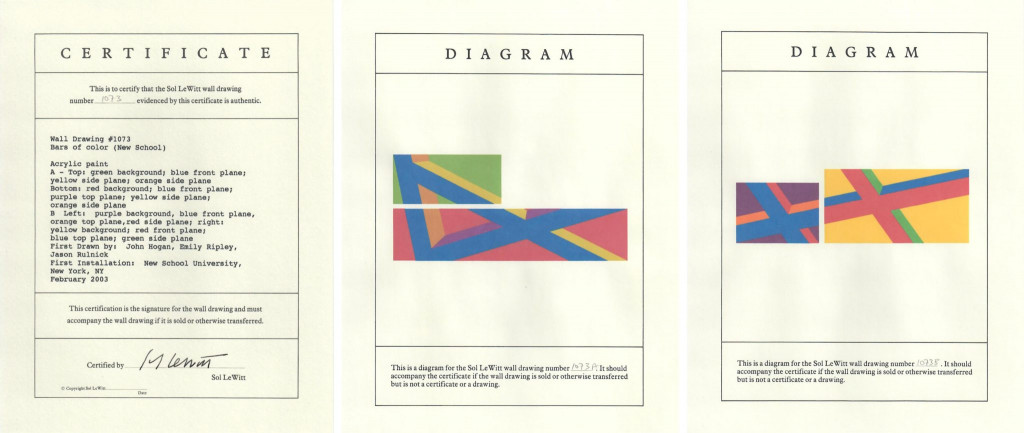

NFTs share a lineage with certificates of authenticity for ephemeral artworks. They have structural similarities with conceptual artworks such as Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings, which include the instructions for execution with a certificate of ownership. If a collector who has executed a wall drawing transfers the certificate to another collector, the physical drawing is no longer considered a LeWitt by the artist’s estate or valued as such by an appraiser. If a collector transfers ownership of an NFT, they may still have access to the digital work, but they no longer have the right to sell it.

Just as LeWitt’s certificates of authenticity bear the imprimatur of the artist’s studio, a smart contract that is deployed directly from an artist’s wallet certifies this unique and unassailable authority. A diligent appraiser would determine that the use of custodial wallets citing the name of the artist in metadata corresponding to the work does not constitute a sufficient proof of authorship, as the process could be used to mint and attribute works to artists without their consent. Nifty Gateway, Binance NFT, and other marketplaces also hold NFTs in custodial wallets after they are purchased. These platforms hold the private keys of all digital assets that they mint and sell. This business strategy may not be surprising in an age of large platforms and monetization of data, but it undermines the power of the blockchain to make it possible to trust information without trusting the recordkeeper.

Some artists hold several wallets, or transfer works to a placeholder “burner” wallet before sale. Artists may engage in these practices for any number of reasons: to preserve privacy, to create self-organizing “filing” systems of issuance for different bodies of work, to defy a platform-enforced structure, or to protect their own secure wallet, analogous to giving out a burner phone number rather than one’s actual mobile number. The artist Nicolas Sassoon, for instance, created a separate wallet in April 2021 to anonymously mint works on the Tezos blockchain under the moniker YMMSH. From an appraiser’s standpoint, the artist’s wallet is the online representation of the artist’s studio, the verified identifier of the origin point. The use of multiple wallets invites confusion and even fraud. Art historians know, for example, that Marcel Duchamp used more than one signature, signing some works Rrose Sélavy. But the use of multiple wallets is more often than not an administrative loss, rather than an artistic gesture. Appraisers need a protocol for verifying wallets of artists and collectors to effectively create standards of digital provenance. None of this will be possible without a substantial collaborative effort involving technologists and blockchain experts. Without the development of these standards, scalable technology platforms will have incentives to take custody of—and therefore recentralize—blockchain-based assets.

This is the first part of a two-part essay on developing appraisal standards for NFTs. Part two, about economic provenance and the audit problem, can be read here.

Muriel Quancard is an appraiser of postwar, contemporary, and emerging art with a specialization in time-based media. Amy Whitaker is a blockchain researcher and assistant professor at New York University.