Connie Bakshi

A studio visit with the self-described "digital shaman," who uses AI to explore ancient culture and the human psyche

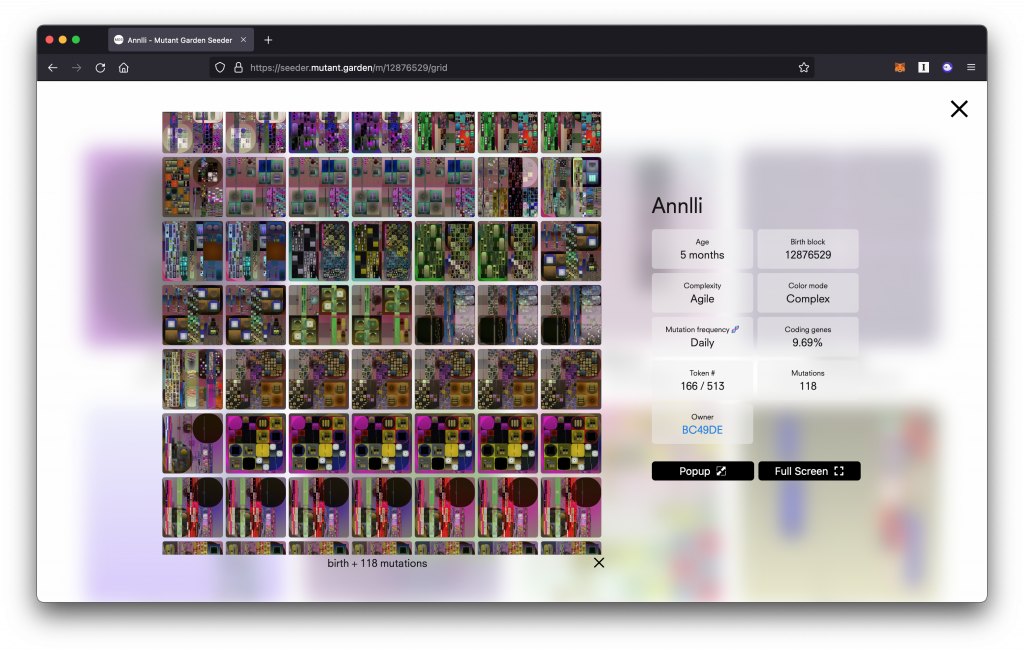

In the work of both Harm van den Dorpel and Jenna Sutela technological processes serve as metaphors for biological ones, and vice versa. Their art stages confrontations with nonhuman otherness, inducing a sense of wonder at the systems that organize nature and information. The two artists met to talk about genetics, computation, complexity, and randomness, and how those concepts play out in their respective practices. They also discussed their experience with NFTs. Van den Dorpel is the cofounder of left gallery, which has been using blockchains to certify and sell digital works by himself and other artists since 2016; in 2021 he released the NFT project Mutant Garden Seeders, in which on-chain algorithms model genetic mutations that evolve with each transfer. Sutela minted her first NFT this year: a video titled YAMSUSHIPICKLE, commissioned by the platform Kanon.

JENNA SUTELA YAMSUSHIPICKLE is a video vanitas, or memento mori. It takes after historical artworks that remind us of the transience of life and the vanity of earthly pursuits. A vanitas often symbolizes something opposed to material wealth, and I had this idea to create a crypto vanitas that would feature the emblematic foods of decentralized finance—yam, sushi, and pickle—rotting away in a little terrarium at my studio for quite a long time. It’s a meditative piece. Making it, for me, was a way to spend some time thinking about this emerging ecosystem that is itself very much alive. Harm, it brought to my mind your Pixel Sorters as a work made in a similar spirit.

HARM VAN DEN DORPEL My Pixel Sorters are a series of algorithmic animations, based on black-and-white found images. The images used are representational, but my treatment emphasizes the artificial materiality of pixels, which seem to have Newtonian properties. Pixels fall down until they hit a dark pixel below, in which case they slip either to the left or right, creating somewhat sad collapsed compositions. They’re certainly about decay and extinction.

SUTELA For Gut-Machine Poetry I inserted fermenting foodstuff into the gut of a computer, using a kombucha culture as a random number generator. The symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast in the fermenting tea drink took part in language generation, and this whole process mimicked an embodied condition that’s usually lacking from computing. The work reflects on the way we compute as humans—how the gut-brain connection works in terms of the microbiome controlling our thoughts and emotions, or how our decision-making is decentralized.

VAN DEN DORPEL Randomness is often lacking in computers. Computers have a clock made with a quartz crystal that vibrates at a stable rate, but it doesn’t do it perfectly. So random numbers are often taken from the imperfections of those vibrations. For Mutant Gardens, I used a mathematical number generator, which returns random numbers, but always in the same order. It had to be deterministic, or else each mutant would be different every time it was rendered, and there would be no point in connecting it to the blockchain. If you played the whole history of Mutant Garden Seeders, you would end up with the same results. It’s all cryptography on blockchain. The block hash is taken as seed for such random number generators.

I don’t often use the word “entropy.” I understand that systems tend to want to evolve toward the highest degree of randomness, or equal distribution. I don’t know if I’m looking for that. I’m trying to provoke complexity, but also to contain complexity or tame it.

SUTELA Engineers at Sun Microsystems used lava lamps to generate random numbers in the ‘90s. I also used them in my work I Magma, but I turned the process around, so instead of randomness I used machine learning to identify signs, patterns and meaning in the bubbling blobs of liquid and color.

VAN DEN DORPEL When you were talking about YAMSUSHIPICKLE, did you say that those foods are the most eaten foods among crypto developers?

SUTELA They refer to some popular DeFi protocols. I guess the whole phenomenon started with the Yam token. Then came the Pickle token and SushiSwap.

VAN DEN DORPEL It’s a symbol for that world. And the lava lamp is also a symbol for hippie culture. . .

SUTELA Yeah, domesticated psychedelia. There’s a web performance company in San Francisco called Cloudflare that uses a wall of lava lamps to encrypt online data, in celebration of their history as random number generators at Sun Microsystems. I’ve been influenced by the history of alternative cybernetics—ideas like British cyberneticist Stafford Beer’s pond brain. In the 1950s he was thinking about how an ecosystem with all its organisms could replace humans as managers of a factory. The environment that we live in is ultimately unknowable and always changing, and maybe biological systems would be better at adapting to unforeseeable fluctuations than computers. The world is not a closed jar. We’re living in an open ecosystem, and I think there’s a lot that can be learned from biology. And our brain is not the limit of consciousness. A lot of my work deals not only with the bacteria that we’re made of but also with the intelligent machines that we cooperate with that function as our interlocutors and infrastructure.

VAN DEN DORPEL I think of DNA in humans or plants as little computer programs, or actually very large computer programs. A tree has millions of leaves, but the leaves don’t have their own specific encoding in DNA. The DNA has programs for making leaves, and these programs are executed a million times, recursively. If the genetic info for each leaf had to be saved individually in the DNA, the DNA would be way too large. So there’s compression, like a zip file. If you unzip the DNA, it becomes larger, because you have recursion, and these algorithms that are in the DNA have parameters. If a gene makes a leaf get smaller and smaller at each iteration, at some point the program decides to stop making leaves, because they are too small to be practical. So I tried to emulate this process of recursion and repetition and variation within a computer program that could also mutate.

Often in generative art, each specimen is forgotten as quickly it was generated. This is why I found connecting generative art to a blockchain so powerful, because suddenly the seed of each specimen is stored permanently. It’s similar to our DNA, which doesn’t change during our lifetime. There might be mutations but for the most part it’s stable. Digital art is defined by fluctuating data and software, but on a blockchain parts of it are fixed, immutably. We don’t know how long Ethereum will exist, but we trust that it will last forever, as long as mankind will propagate it. It feels set in stone, engraved forever, whereas generative art used to seem so ephemeral.

SUTELA That deeper sense of time is key to my thinking and working. I like to consider the time before and after us as well, and how we share a place with other life forms and forces in a broader open system and on a deep timeline.

VAN DEN DORPEL When you see food rotting in a vanitas, you can wonder what bacteria grow on it and from it. You can ask what it transforms into. This kind of thinking gets extreme with the NFT, because it’s not just an artwork, it’s also currency, and the transformation of its value can be clearly expressed in the various coins you can exchange it for. Something I’m still struggling to understand is the extent to which my art is currency. Of course, I benefit from this financially, but sometimes it’s not really clear where the true appreciation lies. This has always been a problem with art. But the transformation—an NFT is exchanged for coins, which then are used to buy another NFT—happens in such a short span of time that I’m left feeling a little confused. Even so I find it fascinating to consider the artwork currency, because it does away with the common hypocrisy of thinking the artwork transcends all that.

SUTELA It’s a bit daunting to be so close to the finance side of things when it comes to NFTs. There’s a lot of financial speculation around artworks and, as an artist, you need to watch it in real time. On the other hand, all this was already happening before, behind an institutional veil. Now the artists are closer to it, and this means they end up with more money from the work and can make decisions about its further distribution. This comes with a lot of responsibility, too. Working with Kanon on YAMSUSHIPICKLE felt a bit closer to a traditional art commission as my work was part of a collection and was not speculated on individually. So this was like baby steps into crypto. Also the vanitas is quite a long NFT—the duration is 3 minutes, 11 seconds—because it uses a protocol called KSPEC that enables attaching larger files in various formats to NFTs. You become an artist because you want to escape thinking about money—and formats, for that matter. Of course you can’t live without thinking about them. But suddenly they are so present.

VAN DEN DORPEL I don’t see how there’s a way back. The toothpaste is out of the tube. Artists are selling their own work and doing just fine. Collectors who do not collect NFTs are called “legacy collectors,” which I think is too harsh. I work with brick-and mortar galleries and setting a price point for physical artworks has become very difficult. Collectors are far more willing to pay a high price for an NFT than for a material object. You cannot flip a physical thing as easily, because you need to ship it, so the market value doesn’t fluctuate with the same acceleration. Now, a commercial gallery show is something you do because you really want to do it, not for financial reasons.

The money part is difficult, but it was important to me to make Mutant Gardens as a work that takes into account these dynamics. It’s a provocation, because NFTs are supposed to be fixed when you buy them, but mine evolve all the time. One might change from a beautiful intricate composition to a gray rectangle, and that impacts its market value. If a collector wants to flip a mutant but it turns gray, people are less willing to buy it.

When is an artwork alive and when does it die? I like the writing of Boris Groys on that question: does art die when it’s acquired by a museum? I don’t really believe that my mutants are alive, but they are changing. In bio art, you stage an environment in a laboratory with a set of starting parameters and then you calculate its changes over many days. That’s roughly similar to the iterations you have in generative art: you end up with something that is predictable but also always different. But bio art isn’t deterministic. Or maybe that’s the big philosophical question. If you made YAMSUSHIPICKLE again, it would not be identical. It would pose the question of what else happened.

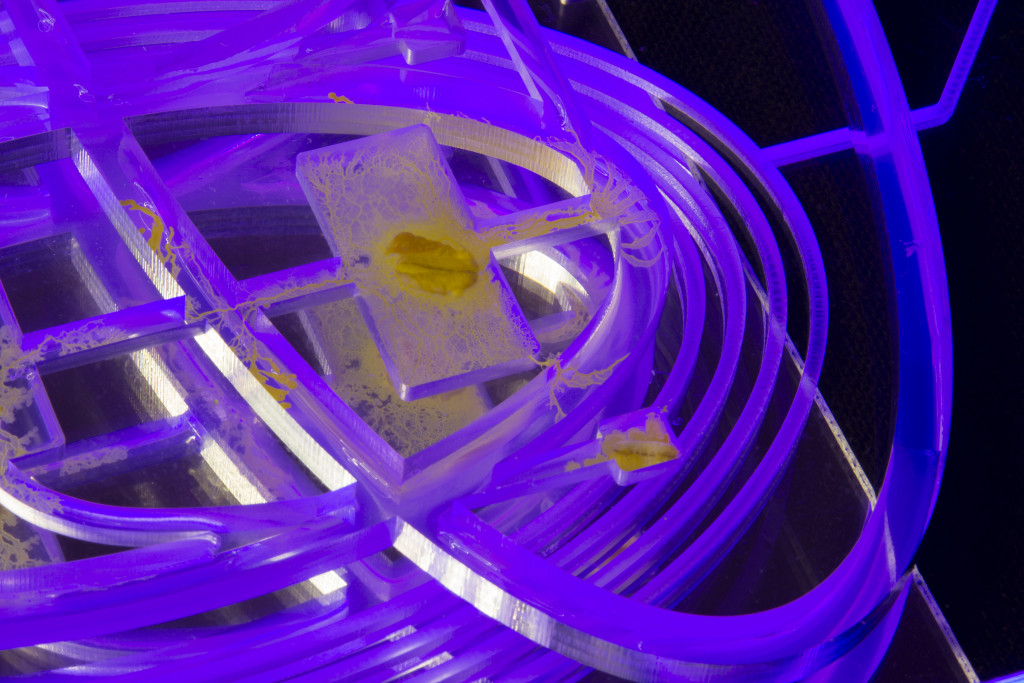

SUTELA That’s right. Different bacteria might enter. It’s like my slime mold works, these large petri dish-like labyrinthsthat are put together in non-laboratory conditions, so other stuff gets in. They’re different every time, not only because of the route the slime mold takes but because of whatever else is there and thrives on the agar that lines the labyrinths. To some extent, you can limit these sorts of chance events when you work with code.

VAN DEN DORPEL There is a potential risk in my code—don’t tell the collectors! My code that generates the aesthetics of the mutants depends on many external libraries that I didn’t make myself. If those developers change their library, my mutants might render differently. So I tried to secure this by freezing the version numbers of those dependencies, but you can never know for sure. At some point a library might be withdrawn by the developer and I would have to use a different one or version. The code is part of a larger ecosystem. Blockchain has this promise of immutability, which to some extent it can deliver, but there are so many more factors at play. Maybe this is similar to your laboratory/non-laboratory situation: external factors will always influence the outcome somehow.

SUTELA At least the slime molds, my single-celled yet “many-headed” co-creators, are extremophiles. They thrive in extreme conditions and are somewhat immortal. Pretty sturdy and trustworthy.

VAN DEN DORPEL They will survive mankind.

SUTELA Like stone.