Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley & R.I.P. Germain

The two artists discuss their use of gameplay as a strategy to make the viewer engage with the difficult questions raised by their work.

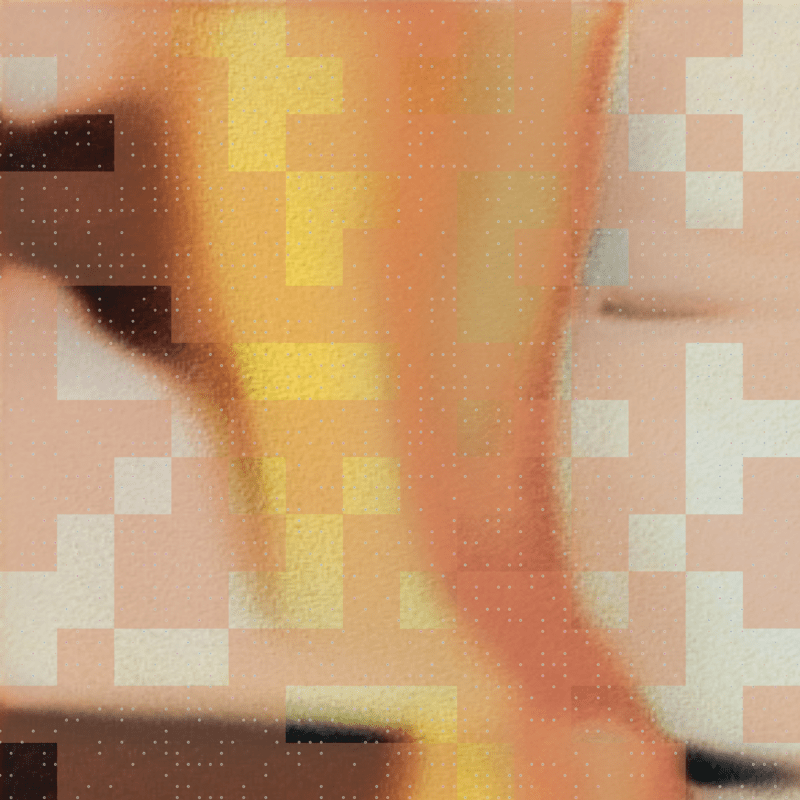

Artists test the limits of their tools and materials—and push past them. But their ideas are often shaped by what those tools and materials do best. This dialogue is part of the process, whether the artist is working with oils, clay, or algorithms. Ira Greenberg has long employed procedural methods, painting and drawing within systems of rules he devises. This led him to coding with Processing, which in turn informed the way he paints and draws—an effect he calls “post-computational.” In recent years he has taken up generative AI to combine his interests in figuration and computing, previously limited by the capacities of algorithms. Ivona Tau is a photographer and AI researcher, who combines those pursuits in a body of work that might be described as photography without a camera, often training AI models on her own archive of images. The two artists met and reflected on how computational tools have shaped their respective practices, and changed their approach to the older mediums they work in. They also compared notes on their experiments in the new field of long-form generative AI, which takes the publishing mechanism popularized by Art Blocks—where the output of an artist’s algorithm is instantly minted as an NFT—and applies it to the outputs of AI models. This year Greenberg launched a marketplace, Emergent Properties, devoted to such projects. Tau employed that format for her collection Infinite | 無限, released by Bright Moments shortly after this conversation was recorded.

IRA GREENBERG The panic about AI is a new version of the historical fear that has been present during any technological change. Painters worried that photography would destroy painting. Obviously, with any technology there are all kinds of ethical considerations and concerns about accessibility. But the displacement of material practice by AI doesn’t keep me up at night.

IVONA TAU Novelties are always scary, especially with technological revolutions that impact not only art-making but many areas of people’s lives. But I think that the search for the best possible diffusion models is like the race that happened in photography, when new and improved cameras were introduced on a steep curve. As the technology reached a plateau, people started going back to older methods of photography, or experimental ways of using silver plates and cyanotypes. After this stage of fear we’re currently in, I suppose we’ll see increased attempts to perfect the technology, and then perhaps a return to older, analog AI technology.

GREENBERG I don’t think more polish and greater detail—five fingers on a hand and so on—will always make better work in terms of what I’m trying to express. Initially I had trouble with Midjourney because everything coming out of it was so highly polished, and I’d been enjoying the earlier checkpoints of Stable Diffusion. But then I questioned my own beliefs, and I was able to get under the surface of Midjourney and find plenty of creative space to work. Tools can be over-engineered. In many ways the creative coding revolution of the ’90s was a response to shrinkwrapped software, when the friction and emergent properties of the creative process were disappearing.

TAU I’m totally with you. I prefer interesting glitches over polished perfection. For me that’s why I use AI. If I wanted to create a perfect image, I would just take my camera and go to Iceland. I don’t need AI for that. But AI has impacted my approach to photography on an unconscious level. I started noticing color the way GANs would notice color. And I started consciously seeking out particular colors and patterns. I’ve also grown to admire the properties that are difficult to replicate with AI—not technical things, like composition or color, but surprising juxtapositions, irony, humor, thematic contrasts.

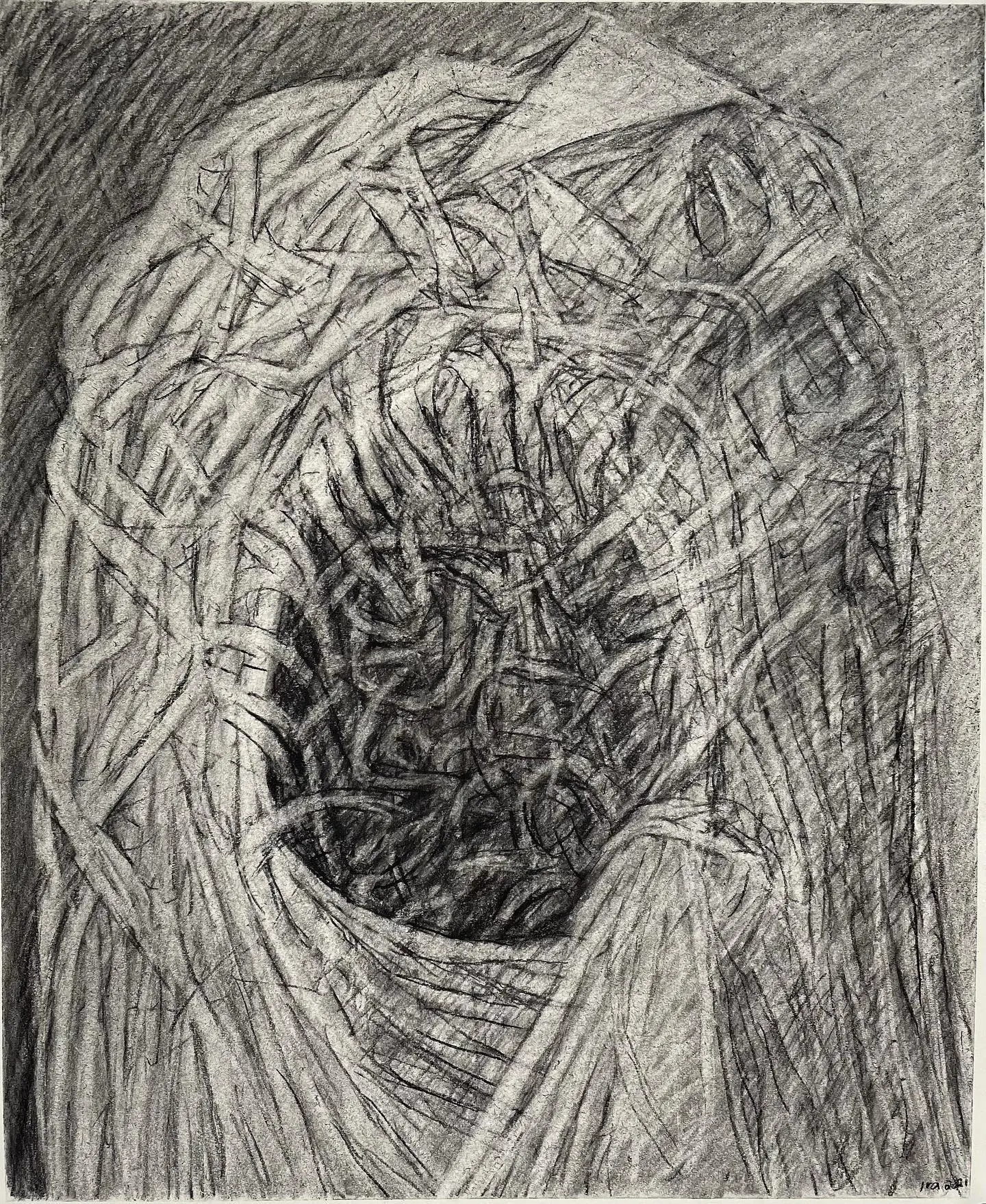

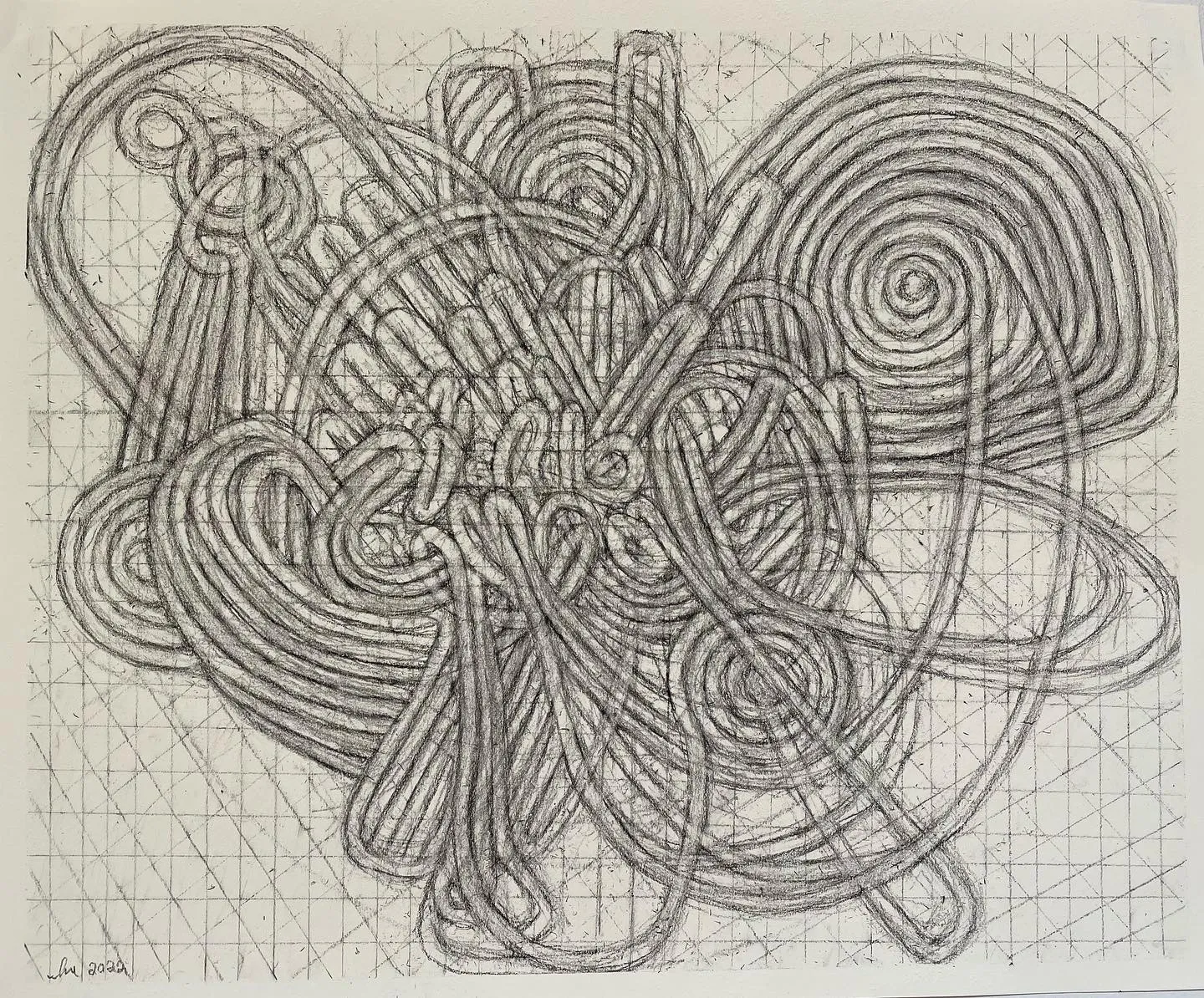

GREENBERG What you said about your unconscious being influenced by your use of this technology resonates so strongly with me. We’re becoming cyborgs in some sense. That’s why I came up with the term “post-computational” for myself. When I transitioned from painting to coding, I was thinking about applying everything I knew about painting to coding. Then at some point I realized I was seeing the world differently because I’d been changed by coding, and that influenced me when I went back to drawing and painting. I think about the idea of embodied algorithms all the time. Years ago I created a project based on the concept of artificial stupidity, because that was so much more interesting and more human than the perfection of artificial intelligence.

TAU The things that we think of as the disadvantages or flaws of the algorithms are the properties that emerge on their own. This stupidity is not something that was engineered.

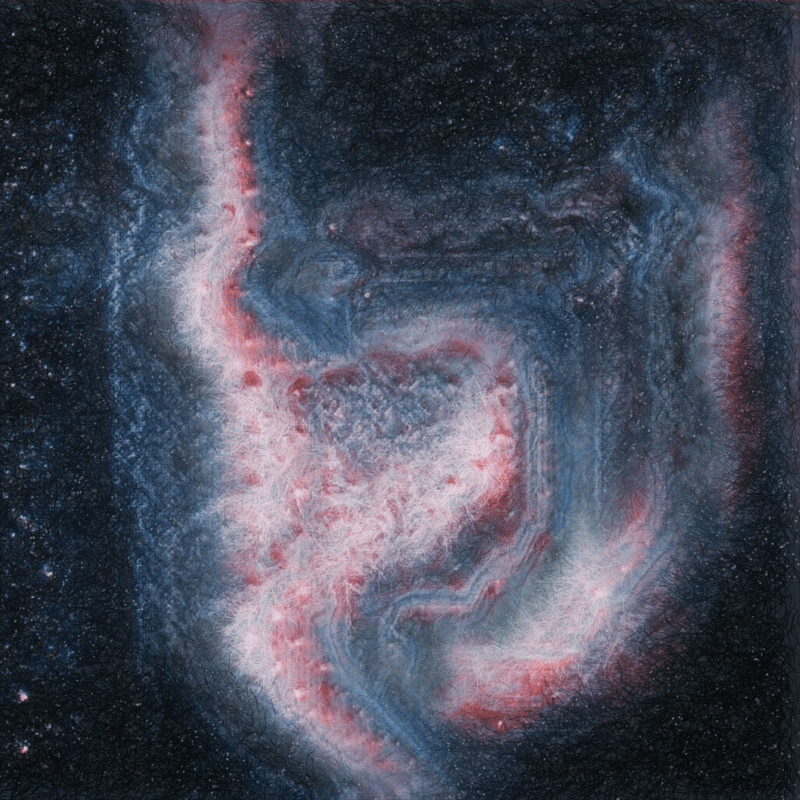

You talk about your work as post-computational. “Post-photography” is a term that is becoming quite popular right now among artists working with generative AI. The term seems to be fluid, as many artists understand it quite differently. To some extent it’s about the new functions of photography in a world where we don’t need cameras to capture our surroundings. But for me, post-photography is about the machine gaze. It’s exploring how computational power can shed some light on those vast data sets that humans can’t process alone. It’s interesting to see how a diffusion model trained on the whole internet captures biases and stereotypes, how this huge, vast amount of information is compressed into something that we can see more easily. And I do that in my own practice, by training on data sets that encompass years of my photographic practice. This helps me see patterns emerge, maybe mistakes, like uneven horizons, that I otherwise might not have noticed because I was looking elsewhere. Leveraging those computational powers is quite an important element of post-photography.

GREENBERG That makes me think about the temporal connections in practice. When I paint or draw, I typically make a piece that then leads to another piece which becomes a series. Most artists work in a cyclical way—we return to themes. It sounds like you’re collapsing that by training against the whole set. Is that right?

TAU Yes, absolutely. Although I also like taking models from previous projects and fine-tuning them on new data sets. It’s an artificial way of emulating the evolution of a human painter. Those models forget quite a lot, so the influence of past work may not be as strong, but some concepts get reimagined in interesting ways. For example, if you took a model trained on the human faces from FFHQ [Flickr-Faces-HQ] and finetune it on a very different dataset, you’d see some horrible things as the model transforms the face into a new domain. It wouldn’t be good for your sleep, but the results might be quite interesting to explore.

GREENBERG It reminds me of a journey with AI in the very early stages of Oracles, my first long-form generative project. I don’t remember what the initial impulse was, but I wanted to see how far I could push the graphic vulgarity, the vascularity and things like that. I got to a point where I started feeling physically nauseous at what had been created, so I pulled back. But I thought it was extremely interesting that I had that physical reaction to things that I was making essentially with numbers.

TAU Some people were drawn to the grotesque, especially in the earliest AI models. There were a lot of uncanny figures of body parts tangled together, some quite creepy imagery. If we assume an image was created by a human being, we can attribute it to their creepy personality. But somehow the absence of a human author, at least as perceived by the audience, makes it scarier.

GREENBERG The mystery of the AI contributes to that feeling for some people. For me, AI is a completely natural extension of creative coding. In a sense, AI is doing for creative coding what oils did for painting. That’s potentially a controversial thing to say, because there are far fewer egg tempera painters today than there were when oils were introduced.

When I started coding as opposed to just using software, creating any type of representational imagery with code was extremely difficult. There are people who spend a lot of time trying to code natural algorithms, and there are clever things like Lindenmayer systems and other approaches to get fractals that approximate natural structures. But those were too formulaic for me. So like most artists I spent time in the nonobjective space, which is fine. But my painting practice spans figuration and nonobjective abstraction, so I had to give up a big part of what interests me. With AI I feel like I can now do creative coding in that figurative space, which is insanely exciting to me.

TAU We took opposite paths. I discovered creative coding very late, through AI. It was such an eye-opener to realize there was a whole community of people creating art using algorithms. That motivated me to engage with those practices and merge them with AI—adding some procedures on top of the outputs, or maybe inside the models. I completely agree that they are related, even to the point where AI is an extension of creative coding. They may be more or less sophisticated algorithms, but they’re essentially the same thing. So the division seems quite unnatural.

I’m often asked about the difference between generative art and AI art. In my understanding, generative art does not even need to have code. We can have generative art with random processes, like throwing dice.

GREENBERG I’d say the drawing I do is generative art. I start with a diffuse type of randomized space and let something come out of it, and I try not to control it for a long period of time.

TAU When using these methods, you have to decide whether to curate the outputs or to create the model and accept the randomness of its outputs. The move from curating everything to allowing randomization during the mint was very scary for me. I was used to working with imperfect models and finding joy in retrieving those instances of latent space that I felt could tell an interesting story. It takes a lot more work to create this perfect model, and it’s something I’m currently struggling with right now in my project for Bright Moments Tokyo, where I’ll be publishing the GAN model weights to IPFS and the blockchain, with outputs generated live from from the model, so it just needs to be almost perfect, or at least I need a degree of certainty that I’ll be happy with the results. Sometimes it feels like being a parent and setting a child free in the world to live their own life. And then some artists have introduced ways of letting collectors influence the outputs, which to me feels like co-creation and engaging other people in your practice. Both approaches are interesting.

While it takes a lot more work to create a perfect algorithm, you still need to find ways to tell the story. If the model is similar to Stable Diffusion and can create anything, you lose authorship. It’s important to be mindful of this boundary.

GREENBERG With long-form generative AI, I learned that if my control was too tight—if I was really confident in the output I was going to get—I was killing the expressive potential. There have to be some pretty shitty outputs in order to get ones that I think are amazing. It’s like giving birth to five hundred children. Emergent Properties is a platform that grew out of discussions between me and my cofounder Emil Corsillo about putting AI on the blockchain. We had to use different platforms to connect our work to the minting process, which was frustrating.

We have a team of five people who love hacking on really hard technical problems. We’re building a modular pipeline that will allow people to mix outputs from GANs, Stable Diffusion, JavaScript, and post-imaging, then go back to JavaScript and add another layer from a GAN, or whatever. The long-term vision is something totally pluggable, so artists can drag stuff around and create what they want. It won’t matter whether someone is a painter or a PhD in AI like you. Ideally the pipeline will work for all of them. It will also allow them to manage the level of control. Artifacts and imperfections, like drips of paint, are really important for recognizing art as something human, so I don’t want to engineer them out of the process entirely.

TAU That’s fascinating. You’re doing an amazing job tackling those technical challenges. Even having a PhD in AI doesn’t necessarily mean you’re strong on the technical side. I understand quite a lot about how the models work, but I don’t have a serious background in coding. When I was studying mathematics, we had to write code on paper—it was about understanding how the algorithms work, rather than making a functional program. So it’s always wonderful to work with someone who is able to put your ideas into life.

Returning to the question of control, how do you determine how much control to exert in your own work?

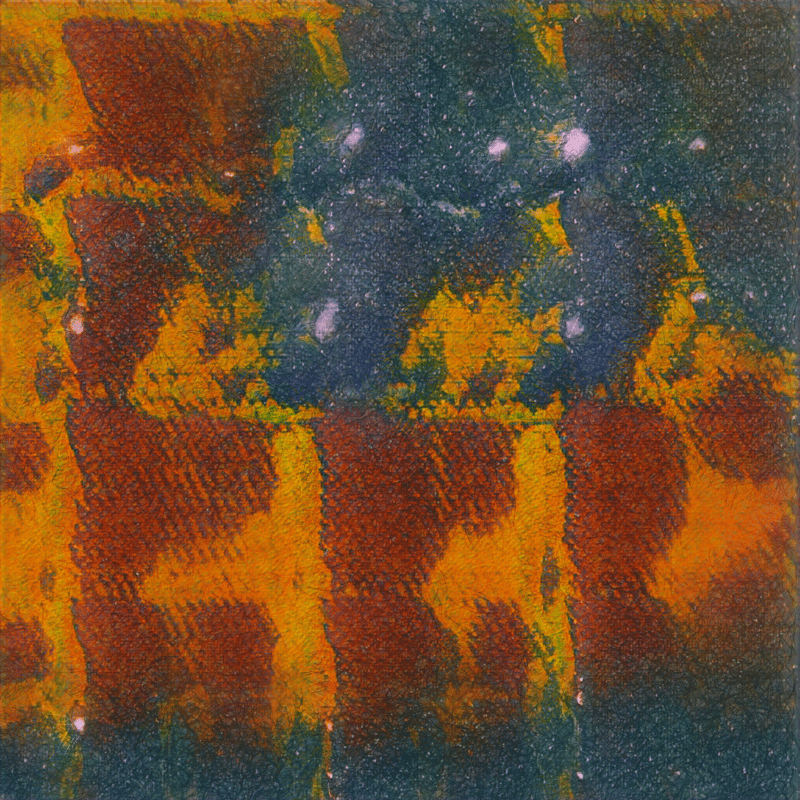

GREENBERG In Oracles, some outputs were way out there. I was shocked in a kind of exciting way. I had to just accept the good with the bad. With Beasts it was about how ridiculously far I could push the range of stuff that comes out of one system. In that case I had an explicit goal, to make a use-case test for the platform.

TAU That resonates with me. I want to keep the joy of the chance encounter. When you play with the trained model and stumble upon something that is so different and so weird, but also so amazing, you want to replicate this experience for viewers as well, so they don’t just see five similar outputs with different variations.

GREENBERG In every Emergent Properties drop, the collection tends to get too uniform, and the artist has to go back and reintroduce chaos.

TAU I guess it would also depend on the size of the collection, because you would approach an edition of ten or twenty differently than an edition of five hundred. You might allow for more mistakes in the bigger one.

GREENBERG Absolutely. Ten would be very scary for me. What’s the size of your collection for Bright Moments?

TAU One hundred, which is also very scary for me.

GREENBERG When these projects are introduced, there needs to be some kind of statement telling people not to judge it by the worst or best outputs, but by the whole.

TAU Yeah, a disclaimer!

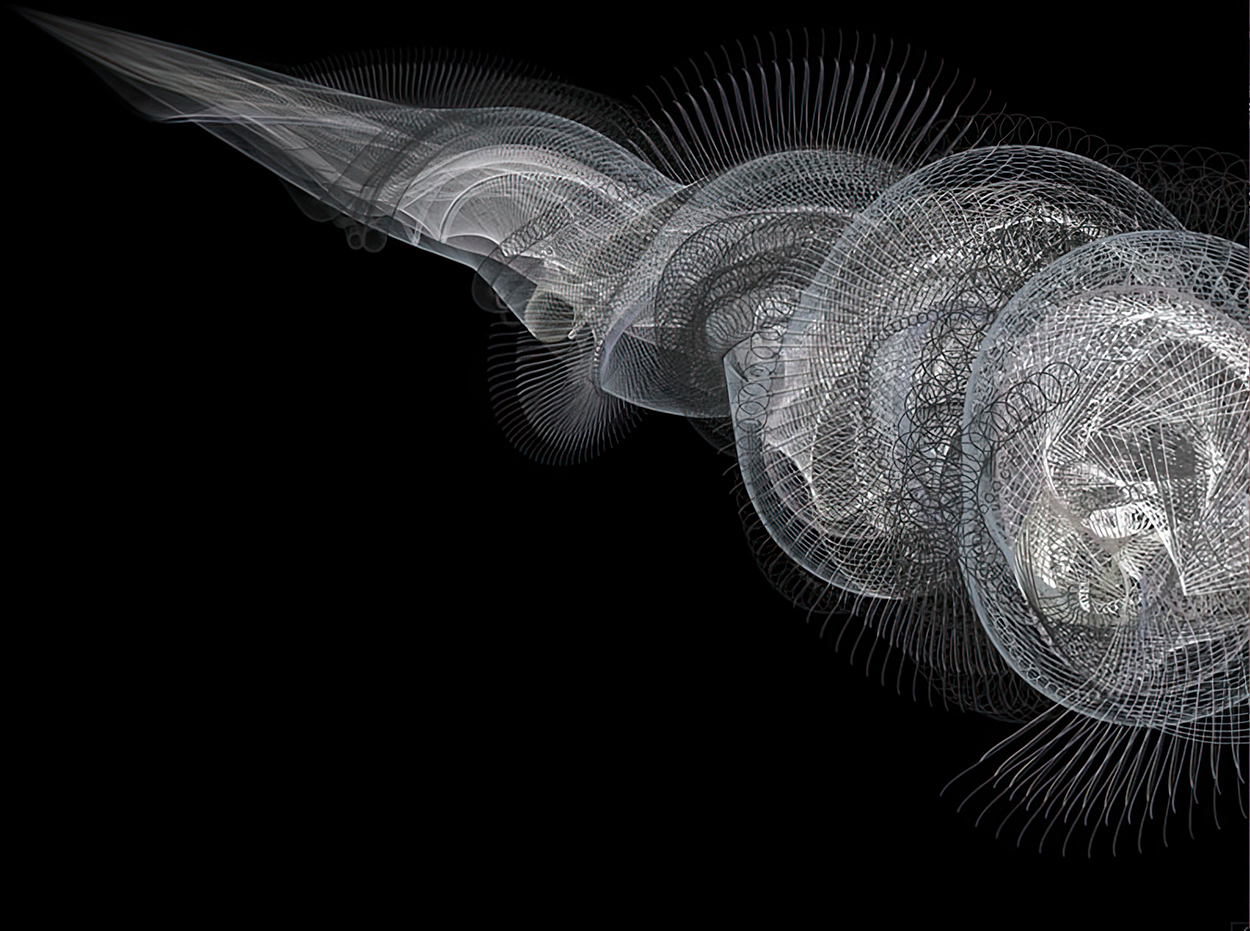

GREENBERG In 2003 I was being pig-headed and trying to do more representational work with code. A long-running project called Protobytes came out of that. I developed a library and hacked on it for many years trying to generate soft body physics with algorithms I wrote myself rather than using an existing physics library. Nearly twenty years down the road, I used that to make Glomularus (2022), my first drop on (fx)hash. Then I wanted to revisit the newer project, so I looked at putting it in immersive environments. I showed it at Refraction x Proof of People during NFT.NYC in 2023, which gave me a chance to deal with the ZeroSpace warehouse environment. The organizers were interested in pieces that would be responsive to the space.

For most of my career, I’ve been an expressive formalist. I tended to reject illustrative narrative in my painting. I’m interested in reading the paintings structurally: I’m often looking at how they’re built on abstractions beneath the surface. That’s how I was trained. Now we can work with imagery through code, when the work starts getting fantastic for me and becomes more illustrative on the surface, I can get out of the academic pocket. But I notice myself returning to these formal constructions, these paintings within paintings.

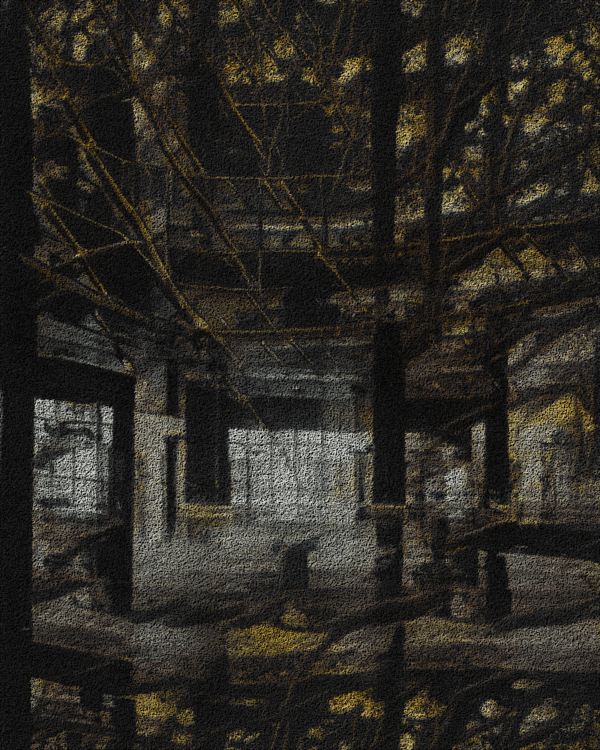

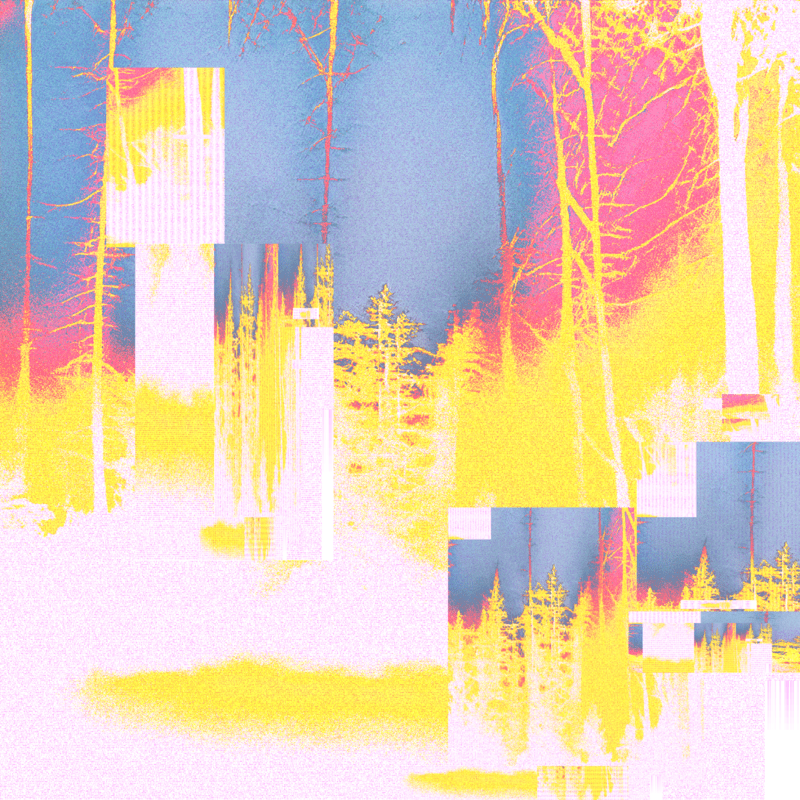

TAU For me, a motivation to explore alternate realities was my interest in Lithuanian paganism. The old beliefs were the initial inspiration for Mythic Latent Glitches (2022)—all the gods that were believed to be living in Lithuanian forests, and the folklore that is slowly dying in our time. Nowadays religion does not play a big role in most of the capitalist world. We’ve moved into a humanist, individualist society. As the world becomes so open, it feels essential to go back to our roots. Maybe AI will fill the metaphysical void left by the absence of mythology and religion.

I don’t like dystopian visions of the world because they make people feel powerless. I try to avoid them in my work, but not always successfully. Many of my works are perceived as dystopian because they show a lot of darkness, a lot of futuristic cityscapes. But I like to bring in organic and mythological themes as an antidote, especially through the connections that AI is able to find between them. That gives some kind of hope.

GREENBERG Crypto is fascinating because it’s utopian for some and dystopian for others. It’s so polarizing. Maybe because I’m getting older, I try to be more positive. It’s so easy to be bitter.

TAU Much of the criticism of AI art is also about how dystopian it is. I think it’s coincidental that we would see the aesthetic of dark fantasy in early diffusion models. But you’re absolutely right. I feel it’s so much easier to be negative about everything. It takes so much courage and work toward the opposite.

—Moderated by Brian Droitcour