The Sphere DAO

Might blockchain technology offer new ways for artists working with performance to sustain their practices?

Jack Kaido is a pseudonymous artist whose abstract works employ bold palettes, expressive strokes, and jagged fragmentations and displacements that emphasize their digital origins. He’s also an avid collector who owns hundreds of works minted on the Tezos and Ethereum blockchains, and he supports the field further through his vocal advocacy for digital painting on Twitter. Below he shares some highlights from his collection, discussing how he identifies strong pieces and how his experience as an artist informs his perspective and taste.

I collect all types of art: oil paintings, prints, drawings, art historical ephemera. When I’m looking at abstract digital art, the first thing I consider is the artist’s understanding and use of color. I look at the relationships between the colors they use. As someone who paints every day, I can instantly detect when another artist understands composition well. To those who don’t paint, a work may just look like shapes that harmonize, or maybe they seem random and chaotic. But painters can spot deliberate choices in the placement of forms and colors, and see the years of practice over which an understanding of composition became habituated.

The above applies to both digital and physical abstraction. But with digital art I also ask questions like: Is this doing something new that hasn’t been seen in physical abstract painting? Does it incorporate elements unique to the digital medium? If so, how well? I own several physical-to-digital pieces, like the ones by Festinalente, who scans beautiful works made on canvas. But I’m moving toward only collecting digital-native art, as it better reflects the tech used to immortalize it, the time we’re living in, and the future we’ll inhabit.

Artists are inescapably drawn to work that shares similarities with their own. But I also love and collect art that is not like mine whatsoever. It’s neat to know about the process behind the work I collect, but it’s not crucial. I’d rather not know how many of my favorite physical artworks were created. The same goes for digital art. I’d rather marvel at how the artist made the work than deconstruct every aspect of its making. That way the work retains all its magic.

One exception is the artist known as Synesthesia. Understanding his process was important to my decision to collect his work. He makes visual images with sound, hooking up synthesizers to a computer with software that produces images that he then edits and refines. Many of them are excellent abstractions in their own right, never mind that they are formed by sound. As a bonus, collectors get editions of the track that was composed to make them. It’s pioneering in several ways.

It’s enjoyable to accidentally discover a process or piece of software that someone else used to create something when making my own work. Sometimes I can identify the software used to make a work when first looking at it, if the artist is using a certain brush, filter, or other tool without taking it any further. At other times I can spot one piece of software but not others that were used to make it. I’ve thought about this a lot, and what it means for the future of digital art. As the number of digital artists increases, the diversity of software available to those artists has to increase at approximately the same rate. Otherwise everyone will eventually be using the same narrow set of digital tools, and the resulting art will be homogeneous—especially when it comes to digital painting. If we can easily identify the software being used now, what will it be like it ten years with many more artists using it? So I think it’s important for artists to build their own custom brushes, tweak existing ones, alternate between different software, and use as many programs as possible to make one work to arrive at artworks that are uniquely their own. It requires time, effort, and experimentation, but ultimately it’s worth it.

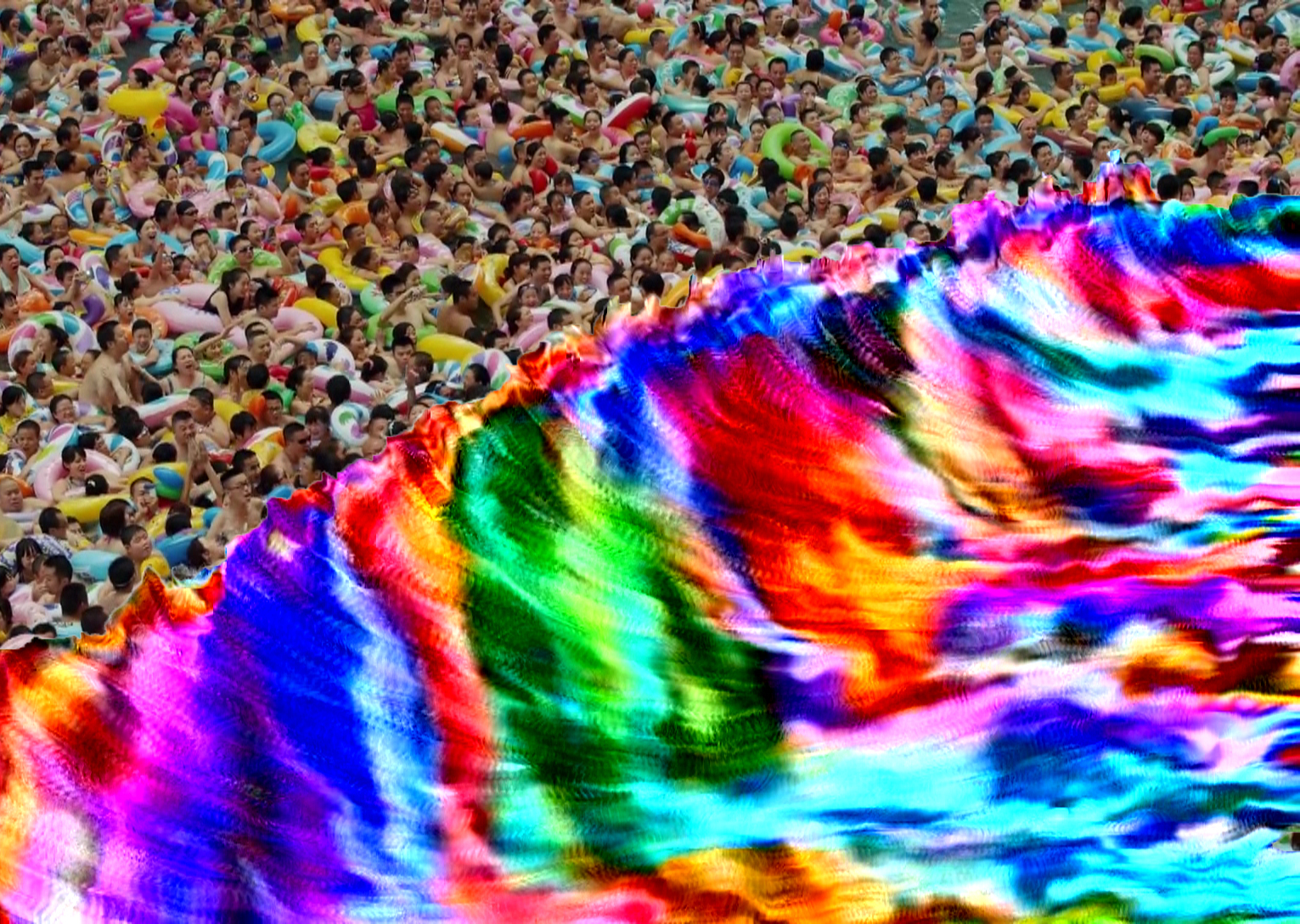

I love generative art and own quite a bit of it. But I do have a soft spot for handmade digital art. Some works I’ve collected are hybrids, handmade then ran through AI or vice versa. A prime example of this is Jaime Derringer’s “Chromesthesia” series. She uses palettes dominated by pinks, oranges and reds, and her images have large digital brush strokes stretching and pulling the color in different directions. She then runs the results through AI. It’s a fusion of color and glitch bound in tight compositions. They are like digital flowers that bloom from between silicon-chip cracks. Her follow-up series, “Chromesthesia 2.0,” puts the images through AI again. I don’t understand the intricacies of how she uses AI, but her work is consistently strong and her style is completely unique, and that’s enough for me.

I’m drawn to highly expressionistic abstract art and its opposite, minimal. The tension between expressionism and minimalist restraint permeates my own art. I naturally lean toward expressionism, and I have to work hard not to fill up empty space. Creating minimal artworks that possess the power to evoke something in another person is a lot harder than it looks, especially in abstract art where the viewer has have no representational reference points.

Lisanne Haack is a magnificent abstract painter. She paints physical oils wet-on-wet, which is difficult because it can easily turn into the dreaded sludge. She paints quickly and is very loose in her placing of ribbon-like forms, yet the composition is always strong. She recently tried her hand at digital painting. It’s a different medium with its own set of challenges, but after just a few tries she was producing works that are just as fluid, vibrant and moving as her oil paintings.

Aertime has been creating digital images for around eight years. His art has influenced my own a fair bit. This may not be obvious, because I’m an abstract artist while his art features representational images and digitally built worlds; mine is 2D while he uses 3D software. But both of us fracture images, spreading elements of the main image across itself, so they poke through the surface. It’s as if an increased amount of aberrant digital information has passed through each image, and you can see their trails, but it’s evocative and aesthetically pleasing.

Bay Fragile creates minimal, unusual, melancholic compositions. Recently he has turned to ASCII art, with darker parts of the composition wholly comprised of numbers and glyphs. Chepertom is doing some incredible glitch work. Yazid is doing all sorts of abstract generative conceptual pieces and performance pieces. Most of the artists I collect are doing new and unusual things.

Pseudonyms are common in the NFT space because cryptocurrency and the ethos of decentralization lend themselves to that. You can anonymously set up a page on a decentralized platform and begin sharing and selling. That’s harder to do physically. In my view, an artist’s identity isn’t important, not as much as people think it is. Anonymity means more focus on the art and less on who the artist is. Less cult of personality, more collective cultivation of ideas. Anonymity also gives artists to build careers without the nonsense that permeates the contemporary art world, like classism and—on the flip side—tokenism.

There are obvious problems with anonymity, of course. Anonymous artists need contingency plans in case they fall ill or die. Who will researchers and curators contact posthumously? What will art history of the future look like, with absences in information? But ultimately historians will still have what matters most: the impact and meaning of the art itself.

—As told to Brian Droitcour