Burn Out

Damien Hirst might have blazed a trail to peer-to-peer sales and digital ownership in the art world. But he’s too attached to the old ways.

These days you don’t hear so much about art’s power to shock, outside some prankish edgelord juvenilia. Gone are the days of the slap in the face of public taste, of épater la bourgeoisie. Performance art in particular is especially tame. Maybe somewhere artists are still enduring pain, or tossing around their own blood and shit, or doing other things that make you nauseous with revulsion or afraid for the artist’s safety. But that work isn’t championed by art institutions, which are more scared than ever of making anyone uncomfortable. When they do present such work, it’s seen in decades-old documentation, in black-and-white photos and videos. Museums would rather steward radical histories than engage with the radical present. They like to present new art that soothes and heals, that gives viewers a space to relax. This is fine by me—I love it when I walk into a gallery and find a place to sit, or better yet, lie down. But it is a bit worrying that the mantle of the disruptive avant-garde has migrated so smoothy from art to the tech industry, which is transforming how we think and live in ways that art once aspired to. And museums are eagerly rebranding art as a space to get away from all that.

Museums like to present new art that soothes and heals, that gives viewers a space to relax.

Lauren Lee McCarthy doesn’t let us get away from any of it. She is one of the few performance artists I know of working today who regularly makes me feel uncomfortable and disturbed, even though her work is couched in the soothing language of care and comfort. Sometimes her installations invite you to lie down! But the therapeutic tone enhances the creepiness. The tension in McCarthy’s work distills a bigger paradox: despite all the havoc that Silicon Valley wreaks, its innovations are presented as fixes that make life simpler, easier, better. Apps make things convenient by harnessing our data to predict our behavior, to sell us to clients, to train more efficiently invasive technologies. And consumers readily give up everything in return. McCarthy shows her audiences how disturbing this dynamic is by taking it to extremes, often inserting herself into familiar situations to embody apps, giving fleshy form to their intrusions. Her exhibition “Bodily Autonomy,” at UC San Diego’s Mandeville Art Gallery through May 25, showcases her two latest projects, Surrogate (2021–) and Saliva (2023–), which take her strategy of embodiment in new directions.

Like a software developer, McCarthy iterates her works over time, adapting the concepts for different venues. Her projects can take multiple forms—as videos, talks, installations, and workshops. I attended a presentation of Surrogate in the fall of 2022. McCarthy came on stage wearing a loose dress over a swollen belly, apparently pregnant. She began by discussing past projects in the format of an artist’s talk. In Follower (2016), McCarthy would spend a day stalking a participant, taking photos and videos of them without letting them see her, to highlight the surveillance that people constantly subject themselves to through their smartphone use. In Lauren (2017–), McCarthy installs hardware in participants’ homes so she can act as an in-home assistant, like Amazon’s Alexa, except in Lauren there’s a real person (the artist) turning the lights on and off and answering questions. In the videos McCarthy made to document these projects, the participants say they find her shadowy presence comforting. The woman who appears in the Follower video says likes knowing she’s being watched, that it makes her feel almost famous. “I want to have a relationship with someone without having to talk to them,” she says. The participants in Lauren likewise appreciated her omniscient companionship.

McCarthy said she wanted to give even more of herself, to dismantle all boundaries between herself and others.

As the talk continued, McCarthy said she wanted to give even more of herself, to dismantle all boundaries between herself and others. That led her to devise Surrogate—a proposal to carry the child of a couple who can’t have a baby on their own, involving an app that lets the parents not just monitor her health and diet, but also send her commands about what to eat and when to sleep. An accompanying video shows McCarthy fielding questions from the would-be parents and the workings of the app. After playing the video, McCarthy admitted that she never followed through with a surrogacy because medical bureaucracy got in the way. In fact, most of the conversations in the video were staged. Then she removed her dress to reveal that her bulging belly was a prosthetic. It got weirder from there. McCarthy launched into a soliloquy about her urge to care for others that made this desire seem pathological. “I need you more than you need me,” she said, her voice desperate and reedy.

What started as a straightforward artist talk veered sharply into performance, in a way that made me question my position in the audience. I had been listening to McCarthy talk about her work, like an attentive lecture attendee. Then, when the Surrogate video played, my feelings modeled those of the parents on-screen I felt confused about why she would want to give away all control over her body, frightened of the risk that entailed. Suddenly I was the witness to an emotional breakdown, sitting captive in the dark as the artist let her neuroses loose. The boundaries of the situation kept shifting, and I could acutely feel how boundaries shift in her art, too. McCarthy’s work not only dramatizes the bad action of giving away data, but also brings out the reasons why it feels good. She wants to care for people and she wants that care to be seen. She wants her audience to watch her watch after others.

There’s so much letting go in this work. What would it look like to hold on?

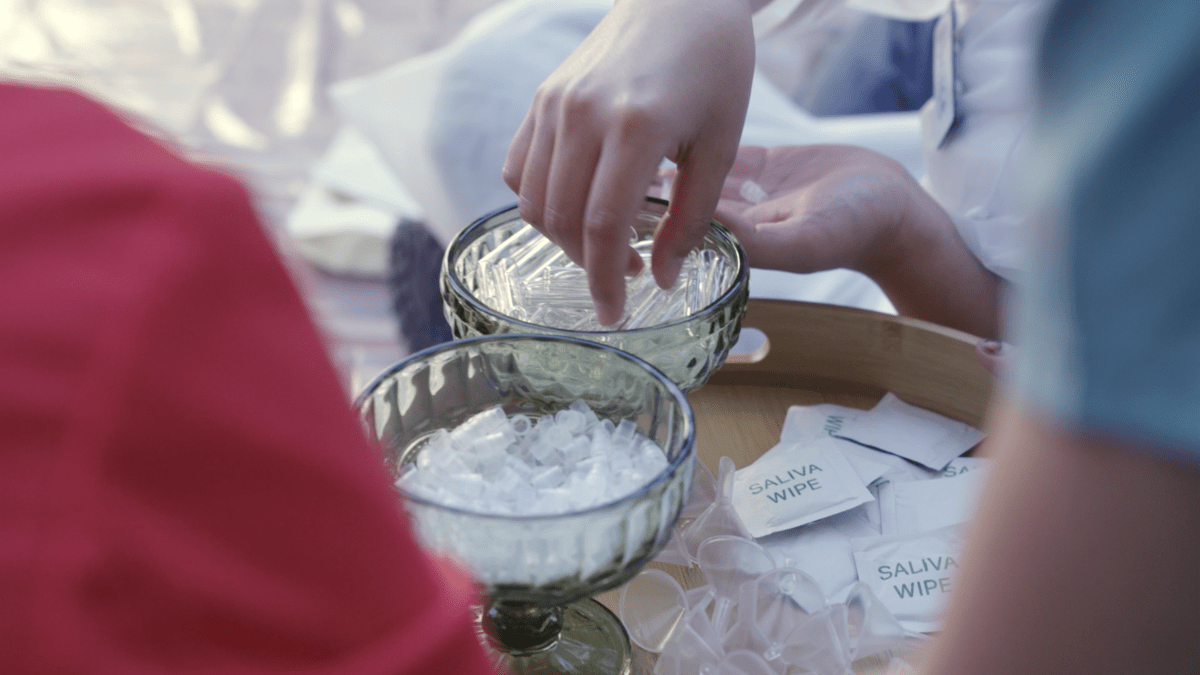

There’s so much letting go in this work. What would it look like to hold on? What protocols can help us manage autonomy of our data, our bodies? In August 2023 I went to an edition of NFT Tuesday, a weekly art-and-tech meetup in Los Angeles, where McCarthy presented Saliva. This project riffs on services like 23andme, where you give up your genetic code in exchange for an analysis of your heritage. In Saliva, you also contribute bodily fluids, but you can make some decisions about how they are to be used. Along with the vials for collecting saliva samples, McCarthy handed out cards. A short message on them notes that we’ve become accustomed to swabbing ourselves and handing the results over to corporations. “Can we determine our own terms around saliva collection?” McCarthy asks. ‘Can we take saliva exchange back into our own hands?” On the back, the card lists possible terms of exchange, with a box next to each one which sample givers can check off: “The saliva may not be used by insured providers” and “This saliva may be publicly exhibited. No identifying information may be shared beyond what is entered on the saliva label.”

Surrogate may mark a limit to how much of herself the artist can give up. I suspect there’s a reason why the presentation I saw took the form of an artist talk, tracing a trajectory that peaks with Surrogate. With Saliva McCarthy is pulling back a bit. Like her earlier projects, it resensitizes us to things we’ve stopped noticing. The difference is that it also encourages us to negotiate protocols and permissions that express our preferences, the limits of our consent. What’s radical about this participatory work is not the ick factor of trading bodily fluids with strangers, but how it coaches the audience to think about sharing themselves with intention and care. It’s art that still aspires to change how we live. How shocking is that?

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief.