Taxation without Representation

Simon de la Rouviere adapted an experimental property tax model to design a new royalty scheme. What might be lost in translation?

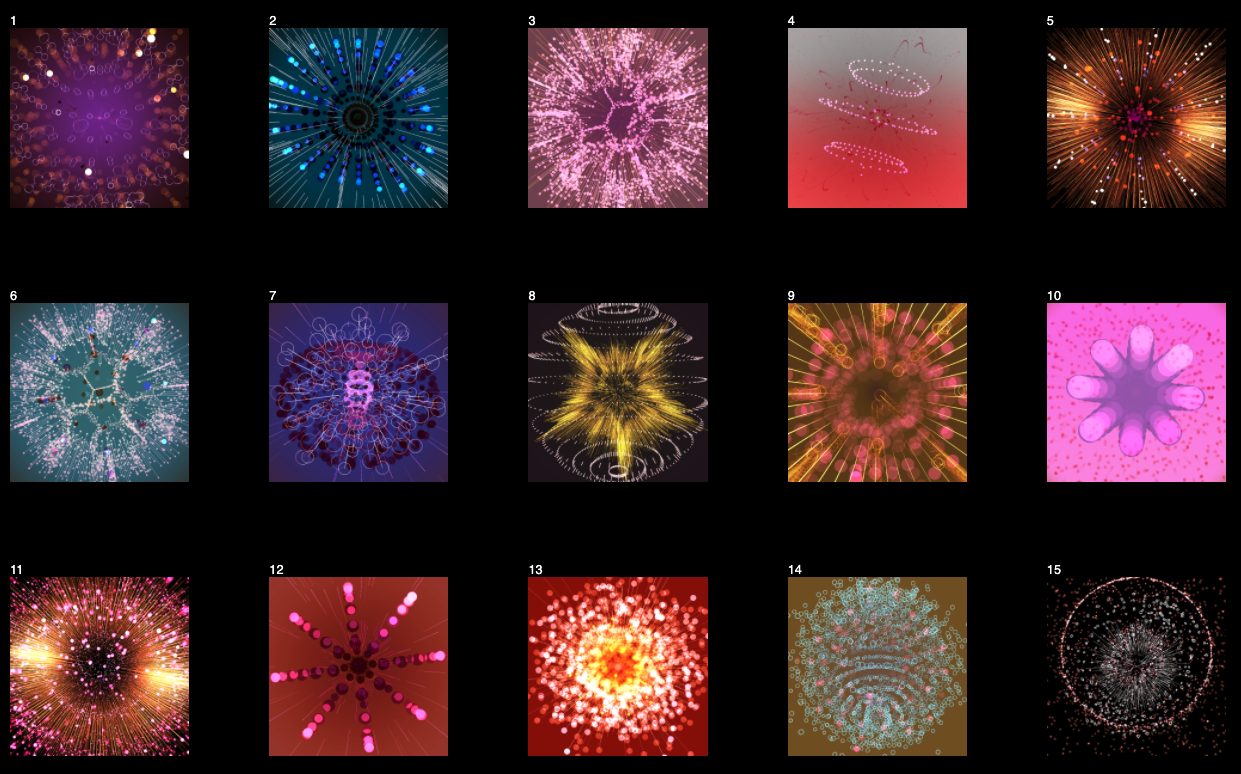

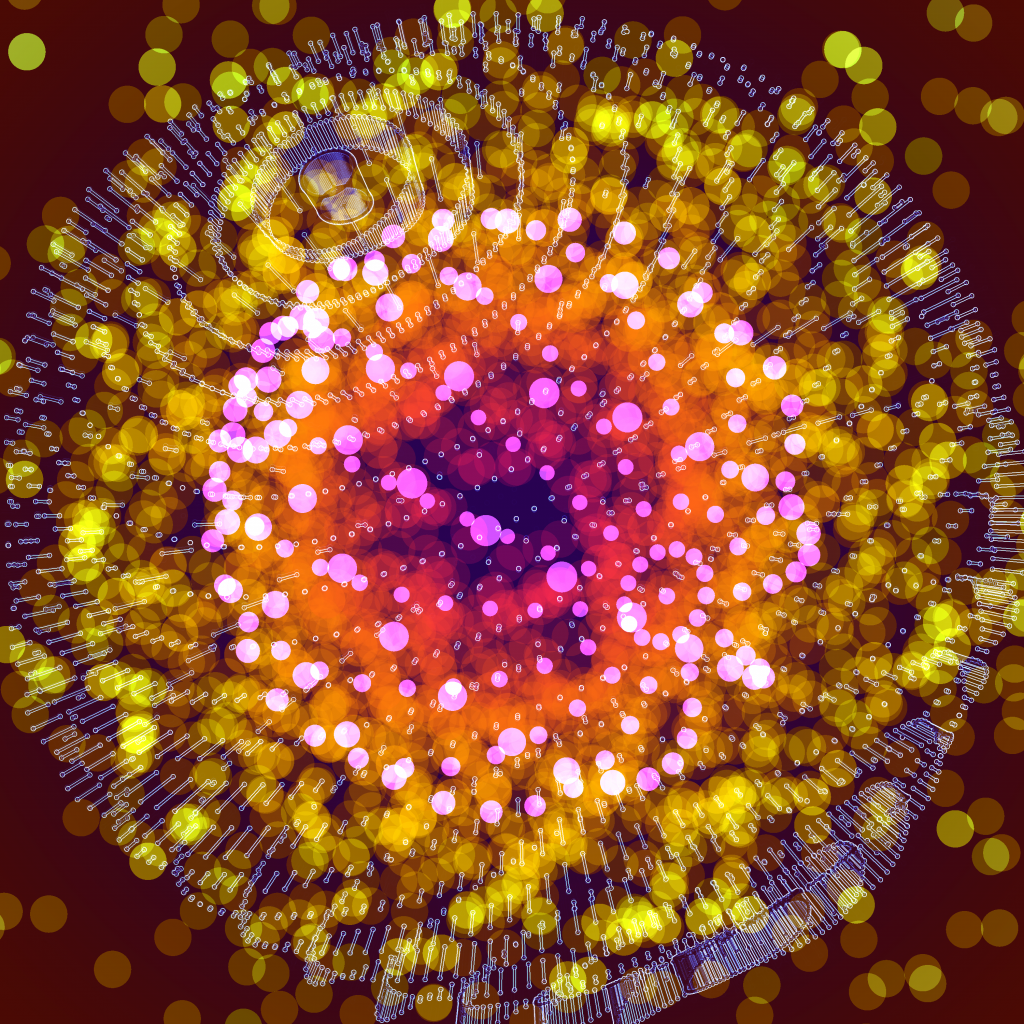

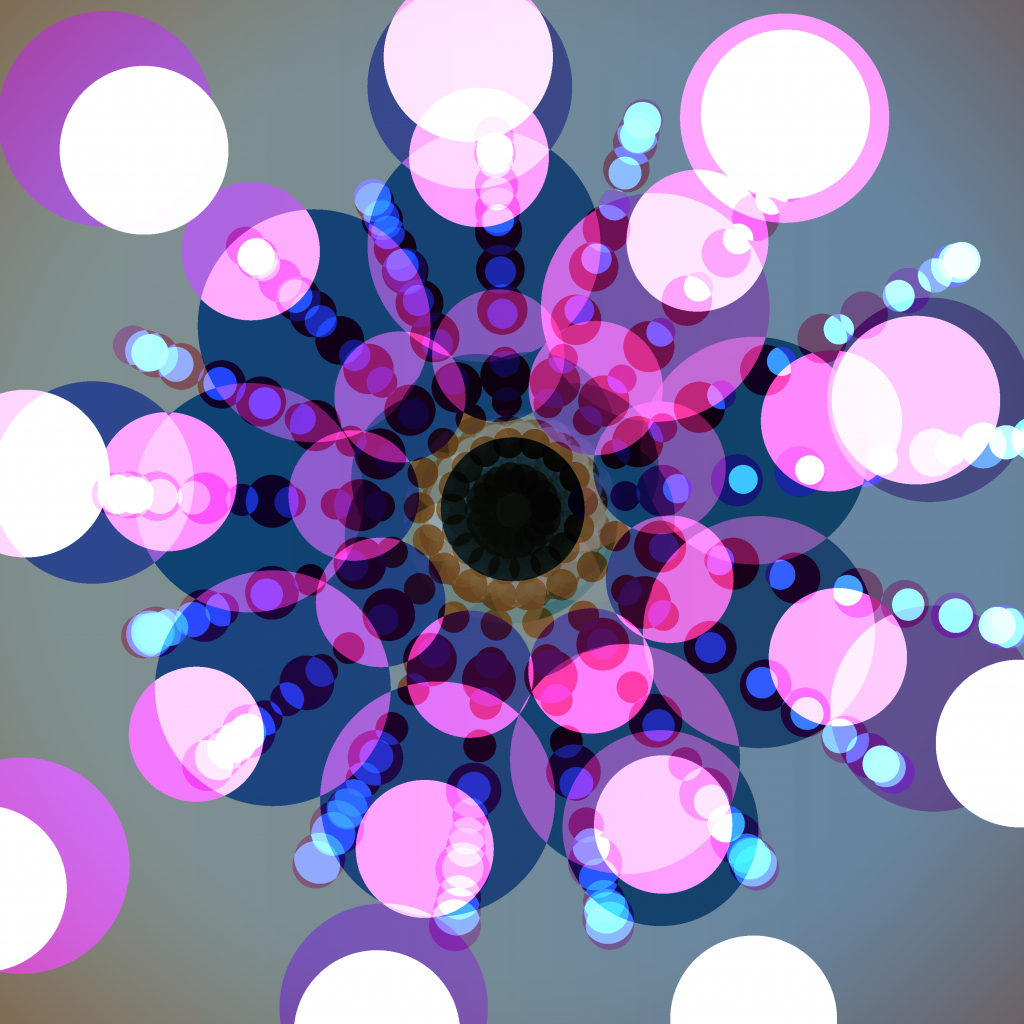

The patterns in Leo Villareal’s Cosmic Reef evoke star clusters and the splatters of rain on windows, the radial symmetry of flowers and champagne bubbles. The 1,024 animations in the project were minted as NFTs on Art Blocks. But unlike other series on the generative art-focused marketplace, Cosmic Reef consists of live simulations that do not loop. The endless morphing can be hypnotic and awe inspiring. Sitting with these shifting nebulae induces meditations on complex webs of associations—the similarities of computer algorithms and biological patterning, the utopian possibilities enabled by electric machinery, and the environmental damage wrought by their energy consumption. To see Cosmic Reef as a set of pretty animations would be like looking at the work of Turner and Whistler as charming impressionistic paintings rather than scenes that capture the effects of industrial pollution, social storms, and political uncertainty.

Like Villareal’s earlier works, Cosmic Reef intertwines engineering efforts with aesthetic achievements. Villareal calls himself a sculptor, though most might think of him as a light artist. He is best known for monumental projects like Multiverse (2008), a sparkling underground concourse linking the buildings of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and The Bay Lights (2013), an installation of 25,000 LEDs that form abstract patterns on the bridge connecting San Francisco to Oakland. While it may be obvious to most viewers that the flashing of lights in these works are somehow controlled by computation, it’s less apparent that these are generative works. Villareal’s light installations express algorithms that he develops and tweaks, often for months on location, to create the final effect, one that is integrated into its environment. The increased interest in generative art brought about by the NFT market offered an opportunity for Villareal to foreground this aspect of his practice. Art Blocks, which invites artists to incorporate a transaction hash into their algorithms so that each collector receives a unique iteration of the work created at the time of purchase, provided the context and the technical infrastructure he needed to do so.

Villareal’s light installations express algorithms that he develops and tweaks, often for months on location, to create the final effect.

The brilliant hues of Cosmic Reef may surprise some who associate Villareal with the monochromatic color schemes of Multiverse and The Bay Lights. But color has cropped up throughout his career. Red Life (1999) is an easel-sized panel of incandescent light bulbs that brighten at random behind an opaque sheet of plexiglass that mutes the effect. Red Life was also his first use of generative systems. Villareal improvised on mathematician John Conway’s rule-based configuration Game of Life, first published in Scientific American in 1970. Every cell on a two-dimensional, rectilinear grid responds to the behavior of its neighboring cells. The development of the system varies according to the initial configuration provided by a player.

The iterations of Cosmic Reef stem from 3D models of simple geometric shapes like a torus or sphere. The work extends the three-dimensional approach to light that Villareal has taken in projects like Illuminated River (2019/2021), for which he designed waves of light undulating beneath every bridge crossing the Thames in London, in order to limit light pollution. For Cosmic Reef, Villareal used Three.js, a Javascript library that renders 2D and 3D images in a browser, to produce similarly nuanced dynamics on the web. The depth and the flow among foreground, mid-ground and background feel cinematographic.

While the history of digital art is often told through an evolution of lens-based practices, an alternate genealogy might be found in light art.

While the history of digital art is often told through an evolution of lens-based practices, from photography to film to video to computer imaging, an alternate genealogy might be found in kinetic art and light art, both of which are connected to computer art through the common use of electricity. What most people call light art, in the vein of James Turrell and Robert Irwin, became associated with phenomenology and installation art as an extension of sculpture. But inher dissertation McLuhan’s Bulbs: Light Art and the Dawn of New Media, art historian Tina Rivers Ryan argues for seeing light art of the 1960s as a reflexive presentation of the nature of electricity. The lightbulb manifests the underlying materiality of the medium and comes to represent electricity’s power. The significance of the history of light art to a digital practice becomes evident across Villareal’s trajectory, from his early use of light bulbs, then to LEDs, and now to his adoption of the light-emitting screen of the computer monitor for Cosmic Reef.

Light is a symbol of thought and inquiry. It is the central metaphor of the Enlightenment, an era disrupted by science, a revival of interest in history and a general questioning of social practices. From gas lamps to the electrification of urban centers, light has contributed to the standardization of working hours and their extension into night. It disrupts circadian rhythms and disorients migrating birds. It powers computers and global connectivity. The title of Cosmic Reef urges us to consider a realm beyond our screen-mediated reality, to ponder the vastness of space and sea. Yet it strikes a somber note by identifying a famously endangered ecosystem, while attached to an artwork produced and sold using a technology widely associated with environmental harm because of its voracious energy consumption. The environmental issue is often used as an easy dismissal of NFTs by audiences who easily accept other uses of energy. But how do we extricate ourselves from the mundane acts that contribute to individual’s carbon footprint, or address the fact that individual energy use is trifling when compared to corporate expenditures? All the benefits of light’s metaphoric and practical applications have come at social and ecological costs. It is reassuring and admirable that Art Blocks has made carbon offset efforts beyond the emissions associated with initial minting of the NFTs.

Villareal’s artistic process is one of adjusting and optimizing, capturing what works and layering further. He describes it as like tending a garden. Disassociating his longstanding environmental concerns from this project proves difficult. With Cosmic Reef, he foregrounds the algorithm that drives the electricity, but that underlying code leads to thinking about the planetary impact of digital culture. Cosmic Reef highlights the material ties between the virtual and the tangible, between the ephemerality of light and the irreversible environmental impact of the infrastructure that makes it available. Our future depends on recognizing them as interrelated. The rules and parameters of one layer influence the options of the next, each key and brushstroke realizing a vision of interdependent sustainability, with damning consequences if ignored.

Charlotte Kent is an assistant professor of visual culture at Montclair State University and an editor-at-large at the Brooklyn Rail.