Handwriting in the Keyboarding Age

Generations of artists have experimented with automated handwriting, illustrating the ongoing entanglement of humans and machines.

LoVid’s exhibition “Hold On” is best reached by stepping through a giant eyeball. It is actually a work by another artist—Serkan Ozkaya, showing concurrently at Postmasters Gallery through April 23—but you couldn’t have devised a more fitting conceptual airlock. LoVid (the studio name of artist couple Tali Hinkis and Kyle Lapidus) delivers a maximalist extravaganza in their work, a riot of vivid color and pulsating pattern. Though their practice encompasses other genres, from multimedia performances to seriously cute scarves, here they show work in just two formats: flat-screen video animations, and painting-like objects described as “digital tapestries.”

Textile is, indeed, the original binary encoding—threads are either warp or weft, over or under, visible or unseen.

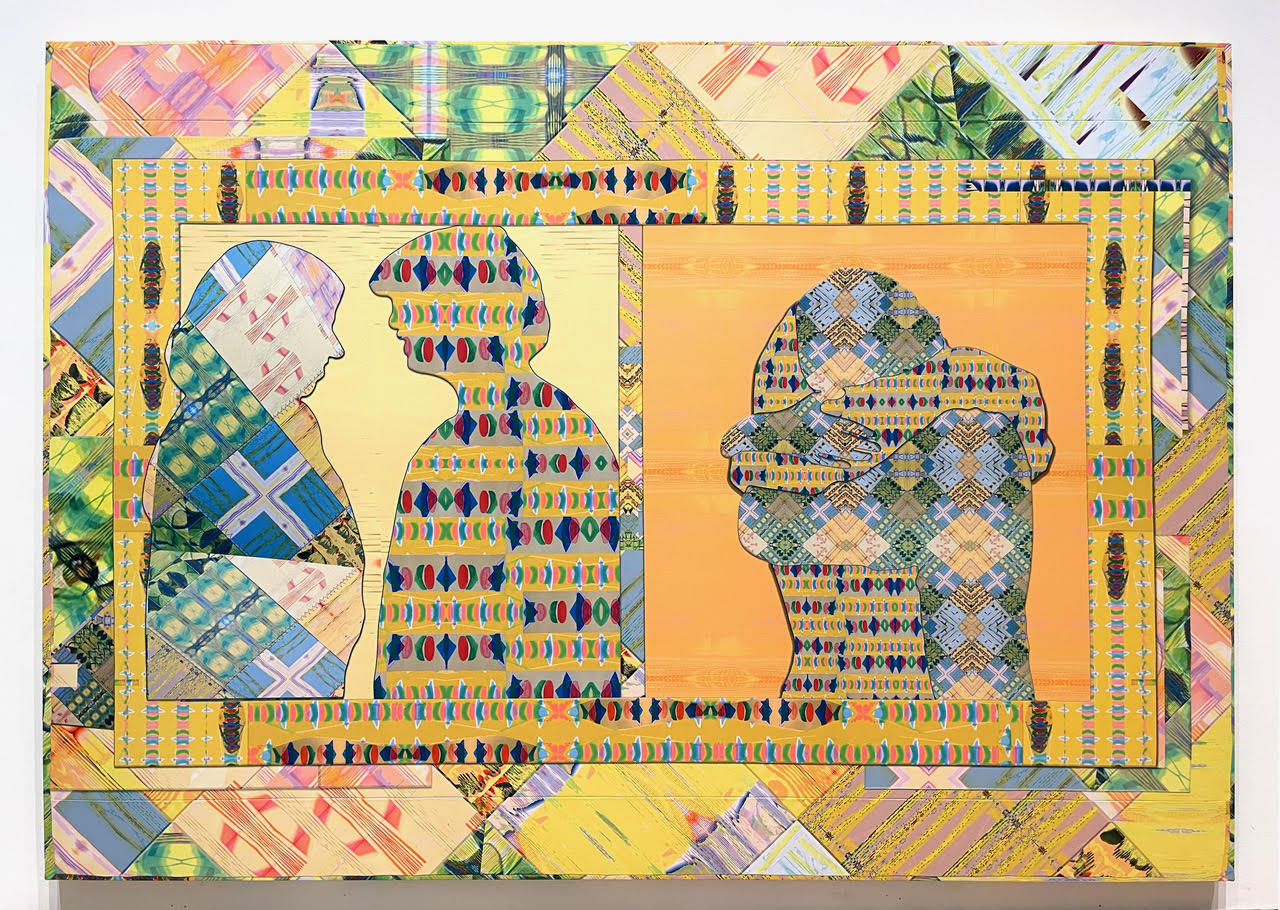

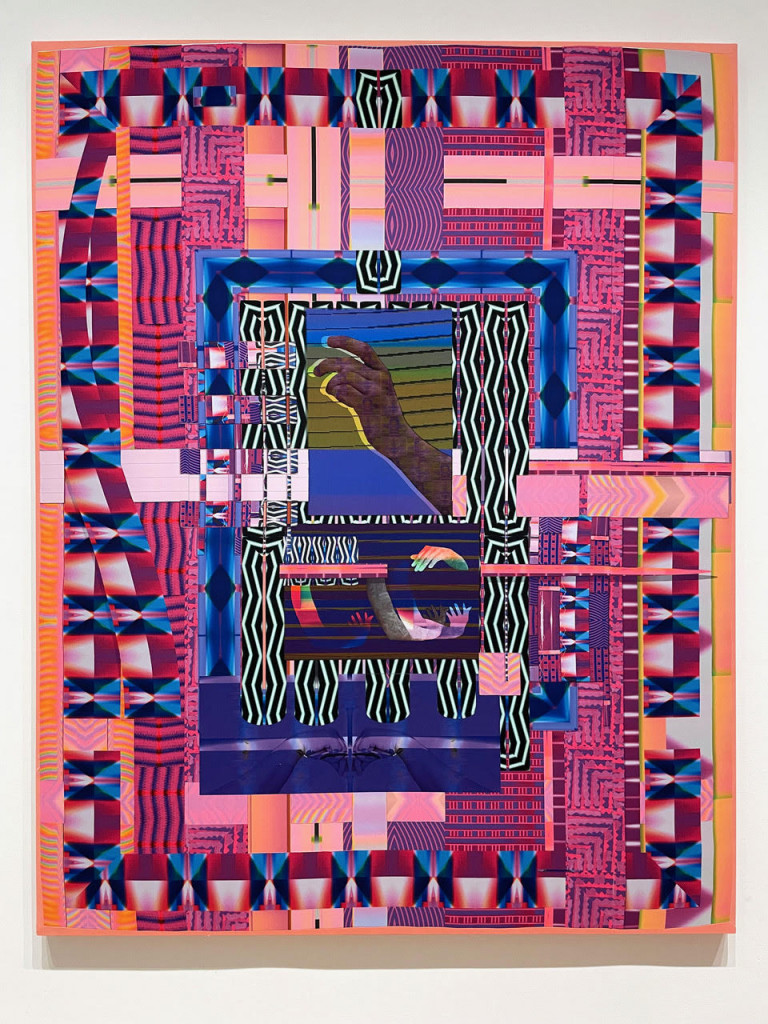

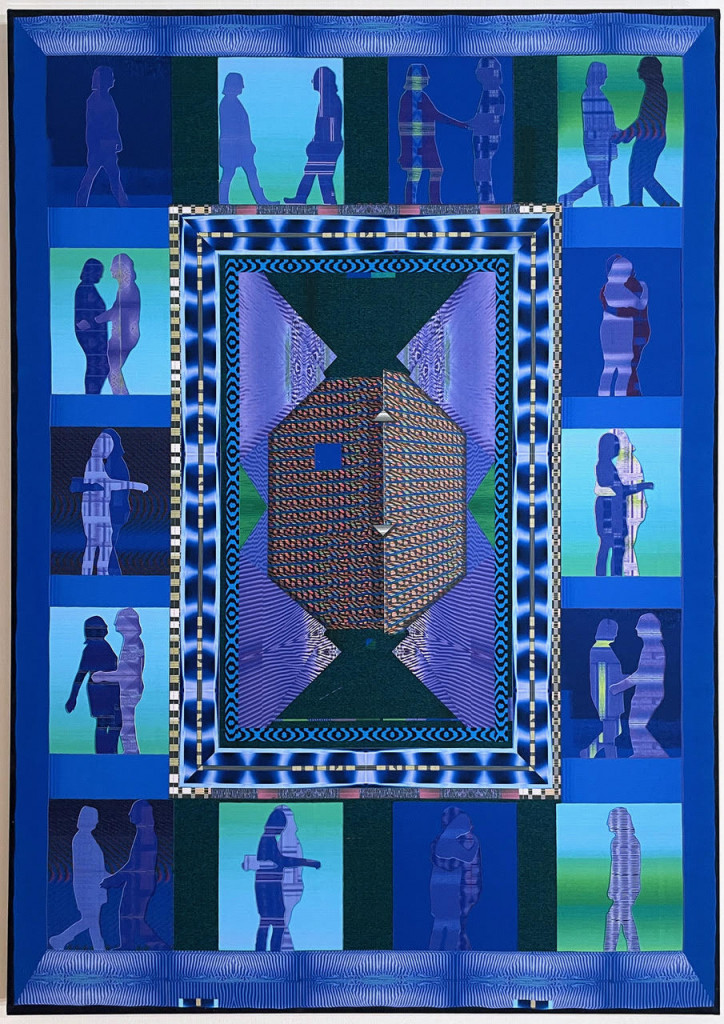

The latter are in fact no such thing, indeed almost at the opposite end of the textile spectrum from conventional tapestry, where the image is laboriously assembled thread by thread. These works are run off on polyester fabric using a dye-sublimation printer. According to the artists (who responded by email to a few technical questions I had), this is a process borrowed from the fashion industry. You can see immediately why they’re interested in it. The hues are intensely saturated, the detail equally so, and the effect is slick and stretchy, the material correlate of a touchscreen. LoVid has however introduced a note of old-fashioned craftsmanship to their textile works, piecing them together from multiple cutouts, neatly hand-stitched along the edges. This patchwork technique allows them to introduce free compositional elements; in a work titled Bubbly Wetware (2022), serpentine curves wander nonchalantly through fields of fizzing psychedelia. The presiding glitchcore aesthetic, which might otherwise seem a bit overfamiliar, is refreshed through this dialectic of hyperreality and handwork.

Though it may not be immediately evident, the animations in the show—which are for sale as NFTs—are also enlivened by a combination of analog and digital. Ever since LoVid was formed in 2001, analog video synthesizers have been at the heart of their practice (an affinity that is captured in their name, which suggests a lo-fi approach to video). Even if you haven’t heard of such analog video synthesizers, you’ve probably seen them in action, perhaps in the work of Nam June Paik. They are to film roughly what a Moog is to music; as LoVid helpfully explains, the video synthesizer “converts live electrical current (from a power outlet) without any other inputs, no camera or computer etc., into RGB colors, patterns, rhythms, pitch etc.” They’ve also made a video that takes you behind the scenes, or should I say, screens.

Just to make things more pleasantly complicated, LoVid then digitally captures and manipulates their analog assets, using editing programs like Photoshop and After Effects. The works in the exhibition all draw on this quarry of visual media, operating on the same principle of oscillation between different states of technology. Look closely, and you’ll realize that the show is something of a love letter to traditional textiles. A printed “tapestry” called Make Room For (2022) includes a trompe l’oeil —a printed photograph of a passage of stitchwork. Throughout the show, there are quotations of canonical fabric idioms, ranging from quilting and shot silks to tie-dye and African kente cloth.

All this technical background is important to the primary theme of the show, which I haven’t actually mentioned yet. It is—charmingly—hugs. Almost every work features people embracing in a friendly, hello-you! sort of way. In the videos, which LoVid call “Hugs on Tape” (2021–22) this movement recurs over and over on a loop, a depiction of everyday human connection perpetually disrupted. Previously one of our most taken-for-granted pleasures, hugging has of course been made dangerous by Covid, rendering the iconography of embrace elegiac rather than sentimental. LoVid reminds us (not that they need to) what we’ve been missing.

The exhibition’s title, “Hold On,” refers literally to this imagery, but it could also be received as an encouragement—not too much longer, we’ll be safely in one another’s arms again. It’s a poignant theme, which LoVid is unusually qualified to address given that they so consistently operate in the gap between the palpable and the immaterial. Now we’ve all fallen collectively into that abyss, the weird non-space where “chatting” happens in a little box instead of at a café table, and “sharing” has lamentably little to do with cake. For all their optical vibrancy, LoVid’s works get you not so much in the eyes as the gut; they speak eloquently to the melancholy of this strange moment in human affairs.

Once all that comes into focus, it’s possible to return to the exhibition’s other primary preoccupation, fabric, and see it in a different light. The historical connection between computers and weaving is now well known, having been explored by many artists and writers, perhaps most memorably by Sadie Plant in her book Zeros + Ones. (She describes how Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace based their difference engine, the world’s first computer, on the Jacquard loom.) Textile is, indeed, the original binary encoding—threads are either warp or weft, over or under, visible or unseen.

For all their optical vibrancy, LoVid’s works get you not so much in the eyes as the gut; they speak eloquently to the melancholy of this strange moment in human affairs.

This is, again, familiar territory for textile people. But by exploring a theme of personal connection, and lack thereof, LoVid rescripts that slightly tired narrative. The fabric they’re really exploring, here, is the social one. This is a fascinating context for the deployment of NFTs, which (it now occurs to me) are less like threads in a woven meshwork than they are like knots, binding media to the blockchain. Those who hold out hope for NFTs and related blockchain technologies (that certainly includes Postmasters, which has been showing digital art since the late 1980s, and proudly announces that it accepts cryptocurrency on its website) perhaps believe that these innovations will do for the twenty-first century more or less what textiles did in previous eras—connect us through trade and efficiently concentrate value, while proving useful in all sorts of unpredictable ways.

Just one of the “Hugs on Tape” in LoVid’s show had a soundtrack. It beat out a quick rhythm, a little like a tickertape, or the clack of a mechanical loom, or the pitter-patter of a human heart, or all of the above. It sounded much like the exhibition looked: like our confounding present, lightened with a bit of hope.

Glenn Adamson is a curator and writer who works at the intersection of craft, design history, and contemporary art.