The Provocateuring Test

Mark Amerika, a pioneer of networked literature, explores the possibilities of collaborating with artificial intelligence in two new books, one fiction and one nonfiction.

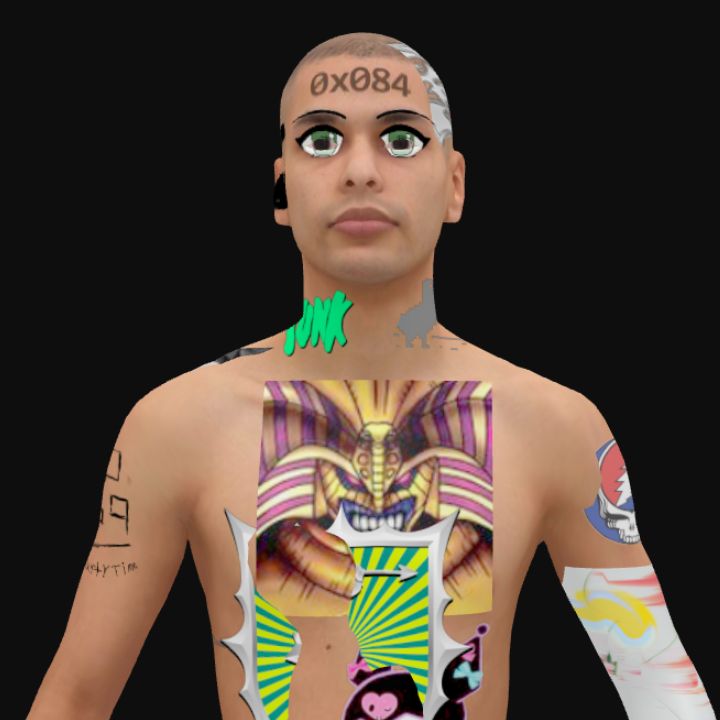

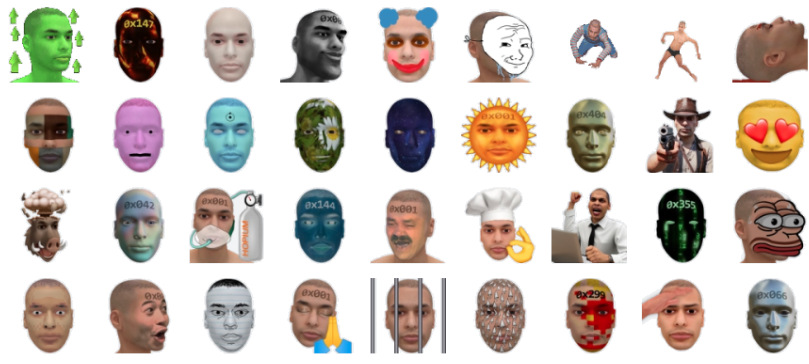

You may have seen Manny Palou out there online, stripped down to his undies and gyrating wildly. Palou, better known as Manny404, is a software artist whose mediums include VR and blockchain. In 2018, he scanned himself and released the 3D model as an open-source asset. In his transformation from man to avatar, Palou assumed the modality of a base character in a role playing game: expressionless, buzzed hair, and clothed only in black briefs. That image has since appeared in countless profile pictures, reaction gifs, and even a mobile game. Palou is just a man; Manny is a multitude.

The 3D model later became the basis for Palou’s NFT collection Manny’s Game (2021). There are 1,616 tokens, each named Manny and each bearing his likeness, but this time customizable with tattoos, accessories, and different poses. Palou wrote lottery mechanics into the smart contract, ensuring each newly minted Manny had a random chance of bearing a unique trait such as holographic skin. In order to unlock a prize pot, a group of collectors quickly set about the task of gathering a “master set” of the rarest Mannys in one wallet, thus concluding the titular game. Manny’s Game now lives on as a Discord community of collectors passionate about digital art.

I see a predictive power in Palou’s work, whose open-sourced body scan predates the metaverse hype cycle by several years. As an artist-engineer, he’s able to catch emerging technology in its infancy and learn its lessons before the wider public does. I can’t help but question what Manny’s Game reveals about the metaverse that it inhabits. The grand fantasy metaverses of Snow Crash (1992) and Ready Player One (2011) have been all but dashed, and it seems that surprisingly simple representations of real things, like Palou’s 3D model, will populate the next generation of virtual reality. Are we seeing a different, more mundane metaverse coming down the pipe?

The denuded 3D Manny exemplifies this mundanity. No matter how wild the customization, Manny’s fundamental character never changes. He never diverts his gaze or cracks a smile. Palou’s digital re-creation of himself is in the company of digital avatars by the artists Skawennati and LaTurbo Avedon, who strive to imbue their virtual representations with unique characteristics and stories. Palou, however, does the opposite. Manny is an intentionally bland prototype with which a dynasty of clones might be built. He sinks into the fabric of the Internet rather than standing on top of it.

Are we seeing a different, more mundane metaverse coming down the pipe?

I asked Palou how he felt about the metaverse now that the crypto market has softened and reality sets in for Meta, which faces billions in losses from its 2021 strategic shift toward VR. “We’ve seen that ‘metaverse’ doesn’t have to be the Ready Player One world of hyperrealistic VR. In practicality, it’s just the Internet,” Palou said. His is a tempered take on the metaverse that correctly estimates where we’re at. “Metaverse” has become a tainted word since it was co-opted by Meta. The company tried and failed to create a semi-realistic virtual world but ended up with an uncanny valley where no one has legs. More successful archetypes for the metaverse have been found in game worlds for decades: World of Warcraft (2004), Animal Crossing (2001), and Second Life (2003) all have avid userbases.

Although the metaverse hype cycle is at an ebb, thanks to market downturns in tech and crypto, the tech giants still see a future in VR—but as a mixed reality of virtual overlays on physical space. Gaming serves as VR’s mass-market entry point and is a forgiving landscape to test out new paradigms on people who are excited by new technology and flexible with its quirks. The workplace, however, is the real moneymaker. Press videos for the Meta Quest Pro and Apple Vision Pro demonstrate disembodied labor, tools, and meeting rooms. This is no utopian vision of a free love metaverse.

The way people and objects are brought into virtual space is being revolutionized, especially when VR is paired with artificial intelligence. A body scan like Palou’s can be rigged and used in videos, games, and marketing without ever speaking to him. Actor union SAG-AFTRA went on strike for six months last year over digital reproduction; studios bitterly fought to retain the rights to scan and replicate actors in perpetuity, dead or alive. Digital representation is on the verge of class war, but Palou has packaged his model as a free digital asset available under a “Do Whatever You Want But Don’t Be A Fucking Jerk Public License.” The license gives anyone complete liberty to use and profit from his 3D model, as long as it’s not for hate. By taking these steps, Palou becomes software himself, realizing what may be the ultimate dream for an open-source hacker.

But why should anybody buy a Manny as an NFT when they can freely download his model? In a sense, Palou has recreated the “free-to-play” game with his body scan. If you want to use his scan as-is, you can, but if you want to modify it, you’ll have to pay up. The customization central to Manny’s Game is analogous to in-game marketplaces, where rare items are farmed and exchanged for personal use and profit. Risk, reward, and, of course, bragging rights are all part of the fun. Palou is an artist who finds refuge from his physicality in an online existence. This attitude toward virtualization is shared by a rising class of people who thrived during the pandemic: gamers and the overly online. Selecting the right avatar is essential to identity formation in these groups, since the social connections they make online are so significant in their lives. This also explains why character customization is available in almost every massively multiplayer online game, and it’s also why some people pay big money for rare accessories. Digital self-representation matters.

Selecting the right avatar is essential to identity formation in online groups.

Palou has been able to set the terms of his own commodification. It has earned him a few ETH, all in service of his long-term project to eschew corporeality. But the rest of us may not get the same deal in the future. Palou set out to make an avatar to release him from the burdens of real life, but those same burdens are closing in on the metaverse. If companies like Meta and Apple succeed, we’ll all have to reconstruct ourselves digitally. Manny’s Game may demonstrate the future gamified mechanics of a mixed-reality productive life. Lucrative profit models adapted from games could follow us into a metaverse that is more work than it is fun. We’ll get all the bells and whistles, skins and accessories, some free and some paid. Your boss’s virtual avatar may be really, really funny. But it will be Tim Cook and his ilk laughing all the way to the bank when we find ourselves shopping for 300 USD virtual suits before the Monday morning VR check-in.

Kat Kitay is a critic and artist based in New York City.