The Outland Review, vol. 2

Andreas Gysin and Sidi Vanetti's numerical art, the collaborative generative art project "N=12," Takakura Kazuki's AI installation, and Mark Fingerhut's malware ride reviewed in brief

Mitchell F. Chan has produced four NFT projects. They fall into two distinct categories: digital riffs on historical works of conceptual art, and artworks that take the form of playable computer games. While this oeuvre might seem to be divided evenly between high and low cultural sensibilities, all four projects are united by the idea that digital art objects can be more dynamic, and far weirder, than merely physical artworks could ever be. Chan is committed to the most serious ideas of conceptualism in the most playful way possible, revealing that conceptual art might have been a game all along.

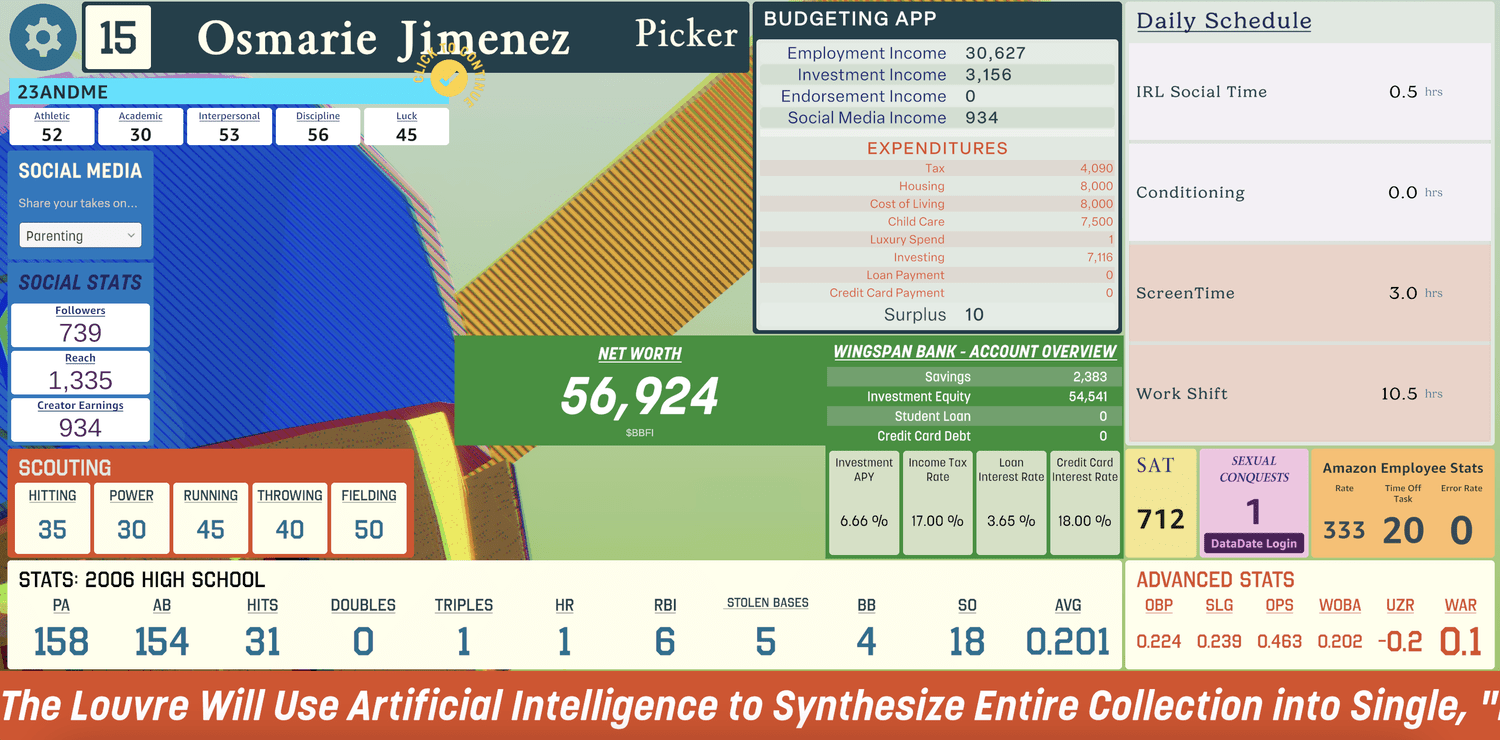

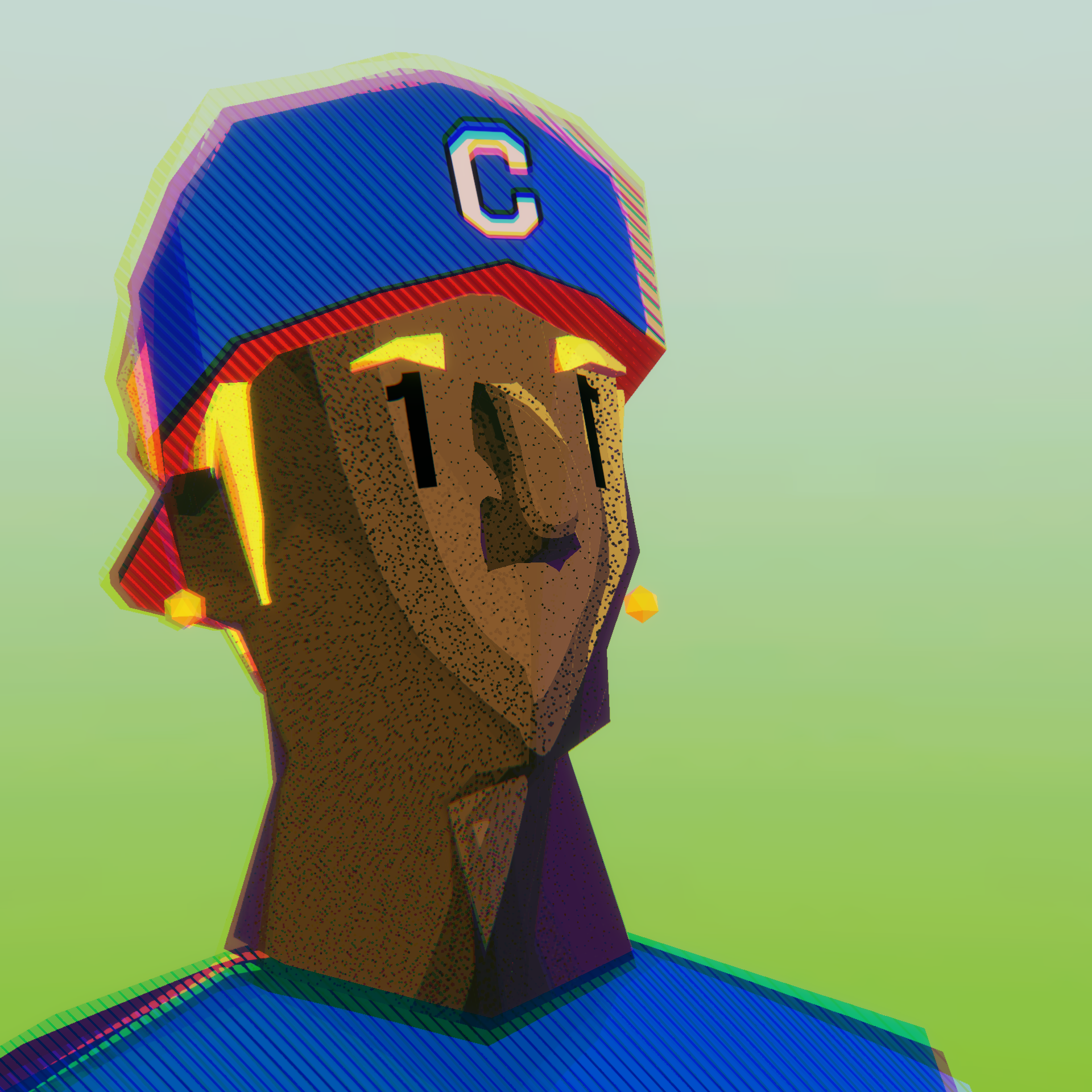

Chan’s most recent work, The Boys of Summer (2023), is a profile picture collection that grants access to a playable game where the user watches the character represented by an NFT progress through seasons of baseball and life. The game can be played by anyone, whether they own one of the NFTs or not, but holders can update the metadata of their NFTs to reflect the results of gameplay. You begin in 2003 as a high school baseball player, with your avatar filling the screen. You select your jersey number and click to raise and lower some key stats measuring your abilities in hitting, running, and throwing. It’s unlike most sports-themed video games in that you do not control your avatar as he plays baseball. Instead, an entire season is simulated invisibly and you are shown the resulting stats for runs, outs, and so on. You can then make other adjustments heading into the next season, in additional stat boxes that appear layered over the image of your avatar. Before long, you are prompted to adjust stats that have nothing to do with baseball, and you begin to see quantified outcomes of other aspects of life, such as sexual conquests and personal finances. Each playthrough of The Boys of Summer leads from high school baseball to a major league draft and beyond until death. When I played I never managed to get my character drafted, and the game shifted into a sweet, somewhat sad life simulator, where I managed relationships, employment, and debt until my character died. Whether or not your avatar becomes a successful baseball player, the consistent experience of playing the game is watching the image of your player gradually be crowded out by more and more statistical interfaces, to the point where the character can no longer be seen. Quantification, in baseball and life, quite literally overtakes everything else.

PFP NFTs provide avatars for people to play not in fantasy gameworlds, but in the “real” worlds of markets and social media.

The Boys of Summer is a game, but it’s also an artwork about how games can extend outside the boundaries that define them. In 2021 I wrote an essay for Outland titled “What’s Their Game?” where I coined the term “ectogame” to describe NFT projects that have game-like qualities without the rules or boundaries of actual games. PFP NFTs are the most common example of this, in that they provide avatars for people to play not in fantasy gameworlds, but in the “real” worlds of markets and social media. The Boys of Summer is not an ectogame, because it provides both an avatar and a gameworld to play in. But in doing so it thematizes the relationship between PFP collections and games. It speaks to the phenomenon at the center of my essay, the notion of game-like quantification bleeding out into real life.

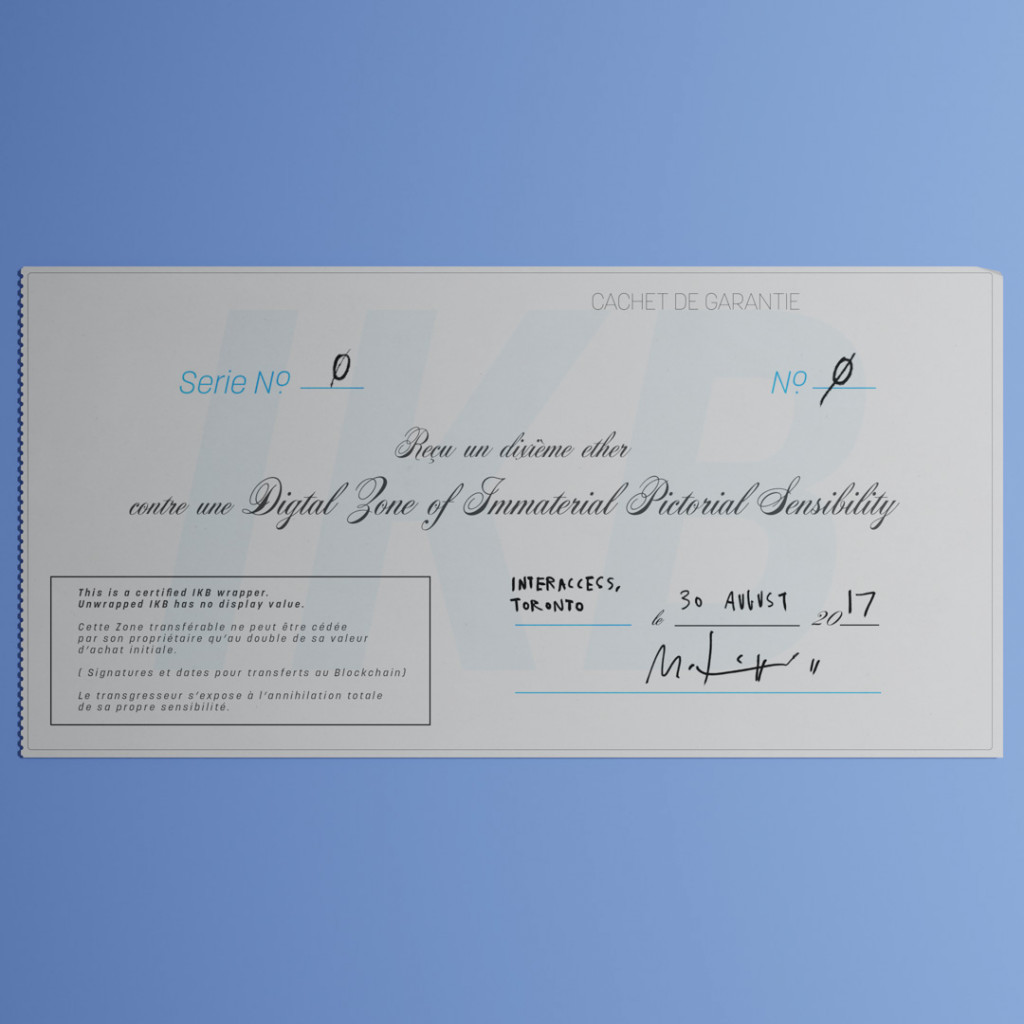

At a glance, Chan’s first foray into NFTs appears more heady and less playful than a videogame about baseball stats. In 2017 he produced Digital Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility, a conceptual NFT project that paid homage to Yves Klein’s Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility (1959). In Klein’s oft-cited work, a set amount of gold was exchanged with a collector for a receipt indicating ownership of a blank space in a gallery that was said to be imbued with Klein’s signature shade of blue. The collector then had the option to “complete” the piece in a ritual that involved burning the receipt as Klein threw half the gold in the Seine, which was witnessed by an art critic. Chan’s digital update is close to an exact copy, except that he chose a lighter shade of (invisible) blue, there is no physical blank space, and the receipts—in this case NFTs—were sold for Ethereum rather than gold. To accompany his homage, Chan wrote a 33–page essay titled “The Blue Paper” to explain the work. The essay displays an ambition that borders on hubris, at times a little silly but ultimately very endearing. Reading the essay now—in light of the intervening six years of growth and turbulence in the NFT world—it’s striking how insistent Chan was on pointing out that the work could be owned and experienced without any material component. Just a few years ago the idea of buying and selling certificates for immaterial artworks was not common. It required the legitimizing callback to conceptual forebears like Klein, along with lengthy explanations. Chan’s NFTification of Klein’s famous work almost seems obvious in retrospect, but perhaps that’s because it was essential, or inevitable. The design of the Ethereum network, with its ability to exchange contracts that attest to the value and ownership of non-objects, already echoed Klein’s receipts. Chan made the connection explicit.

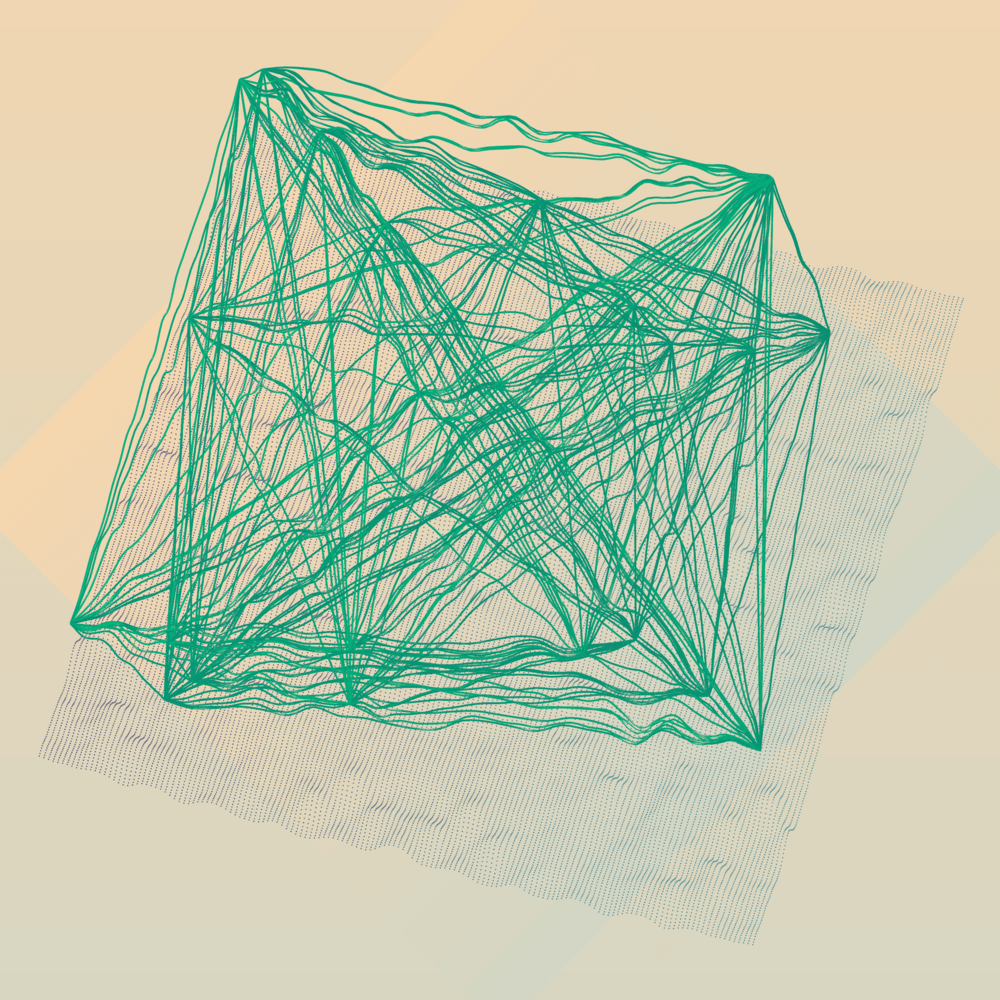

Digital Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility set the tone for Chan’s other work in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. Like Klein’s provocation decades earlier, it presents an if/then condition: it is essentially a program without a computer, where the state of the artwork is conditional on the action of the owner. Chan understood that conceptual works from previous generations were analogue precursors to the kind of art production that NFTs would make more widely known and commercially viable. His second NFT project was LeWitt Generator Generator (2021), which translated the instructions for a Sol LeWitt wall drawing onto digital, algorithmically generated virtual walls. LeWitt’s wall drawings were another proto-NFT, in Chan’s view, because the collector or institution would purchase only a certificate that contained instructions about how the drawing was to be executed, which would be completed by someone else. This mirrors the trend of “on-chain” NFTs, where the smart contract contains all the code needed to generate an image, rather than a link to an image file stored elsewhere. Chan shows that Klein and LeWitt’s contracts-as-artworks are dynamic entities that are not complete until engaged by the collector. Klein and LeWitt were designing games; they encoded sets of rules for works that lie dormant until someone plays them.

From this vantage point Chan’s move into playable video games as artworks is a straight line. In 2022 he released Winslow Homer’s Croquet Challenge. The game allows the user to play a 3D version of croquet inside Winslow Homer’s painting The Croquet Players (1865). Homer’s image of the game was produced shortly after the Civil War. In Chan’s version, the yard on which the game is played is bound by a giant gilded frame—like the original that hangs in at Buffalo AKG Art Museum—alluding to the idea that games are contained zones, delineated from real life. The shadow of the war can still be perceived, however, in the dialogue of the platers and by the presence of an all-Black chain gang on the landscape beyond the frame, ostensibly emancipated but still in shackles. Chan is again playing in art history, this time reaching back a century before Klein and LeWitt.

All of Chan’s NFT works are predicated on the idea that digital objects can change states and respond to new inputs—they can be played.

All of Chan’s NFT works are predicated on the idea that digital objects can change states and respond to new inputs—they can be played. The two most recent works, which are games in a very literal sense, do not simply update conceptual art strategies for a digital era, but also push those strategies to the point where they begin fraying the barriers between genres of creative production. In a 2013 piece in the New Yorker, reflecting on MoMA’s acquisition of the computer games Sim City 2000 and Dwarf Fortress, Gabriel Winslow-Yost observed that “To make any sense at all, games need to be not just played but played seriously, with a sweaty, childish abandon totally unlike the cool passivity of an art viewer.” Chan’s NFTs apply this “sweaty, childish abandon” to art history, first as homage, then as fulfillment and extension.

Kevin Buist is a critic, curator, and filmmaker living in Grand Rapids, Michigan.