Scam Artist

Is crypto a scam? Is art a scam? Steve Pikelny’s winking answer to both questions is yes, and his work explores what happens when the art and the crypto are one and the same.

In 1965, New York’s Museum of Modern Art sent a Christmas card that turned out to have a surprisingly significant legacy. Asked to contribute an image to the museum’s annual holiday mailing, Robert Indiana had offered his now-iconic “LOVE” design, which soon spawned paintings, prints, and a series of large steel sculptures that continue to proliferate today.

MoMA is again experimenting with greeting cards, this time with a twenty-first-century twist. Introduced in October, MoMA Postcard is an online community initiative where the public is invited to create pixel art “stamps” on digital postcards that are collaboratively created and collectively owned on the blockchain. The stated goal is to get people to “collaborate, learn, and experiment with web3 technologies.” The project launched with “First Fifteen,” a set of postcards showcasing the collective efforts of fifteen artists who are well known in the web3 space, among them Dmitri Cherniak, Sasha Stiles, and LoVid. If Indiana’s “LOVE” card coincided with and reflected the ascendency of pop art in 1965, MoMA Postcard is launching in 2023, at a moment when web3 hype has been largely deflated by monkey jpg jokes and schadenfreude-laden coverage of Sam Bankman-Fried’s fraud trial. Nevertheless, MoMA Postcard manages to establish a system for the creation and exchange of digital art that serves as a microcosm for what’s possible in web3.

MoMA Postcard is designed in a subversive and self-critical way. It’s an anti-NFT NFT project.

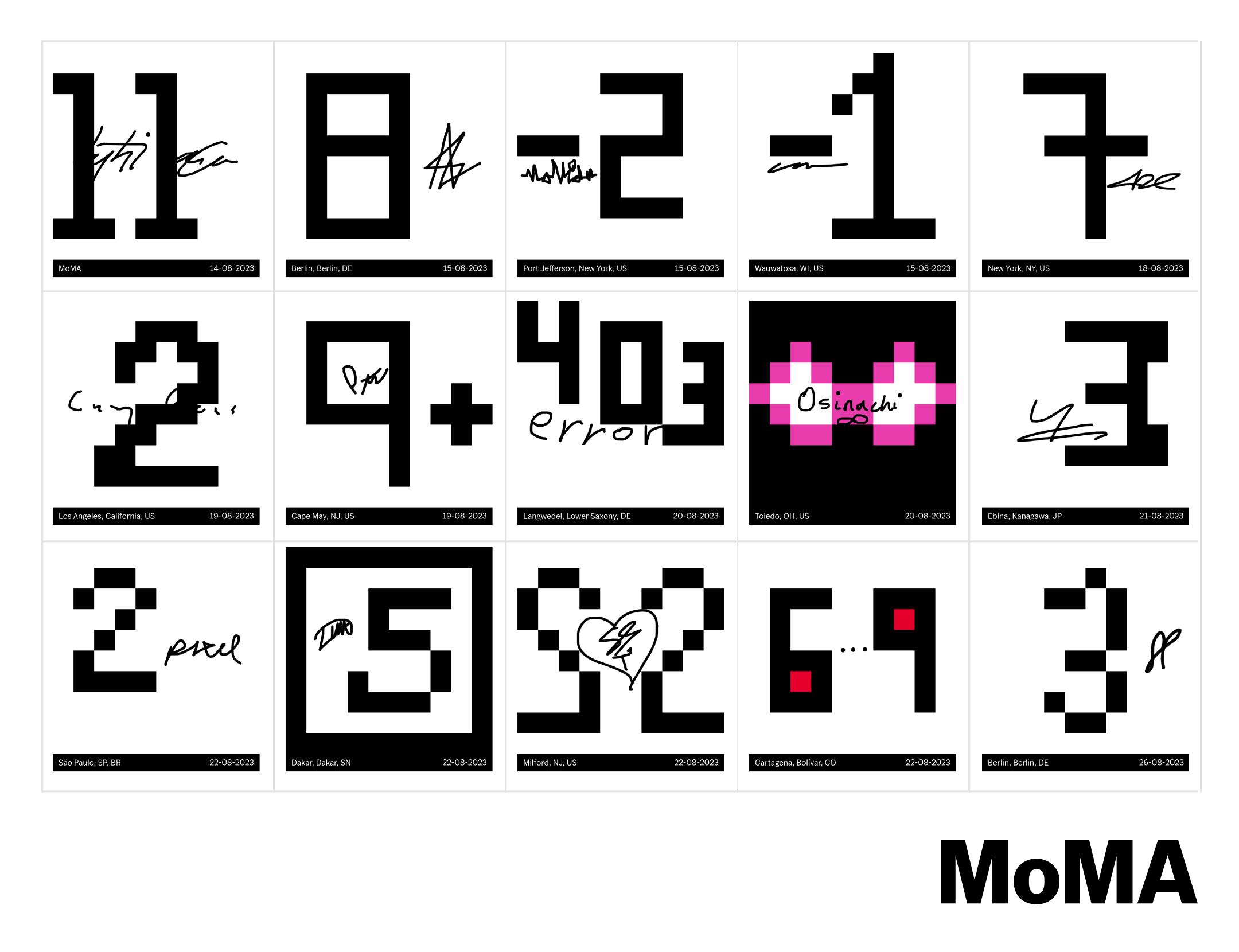

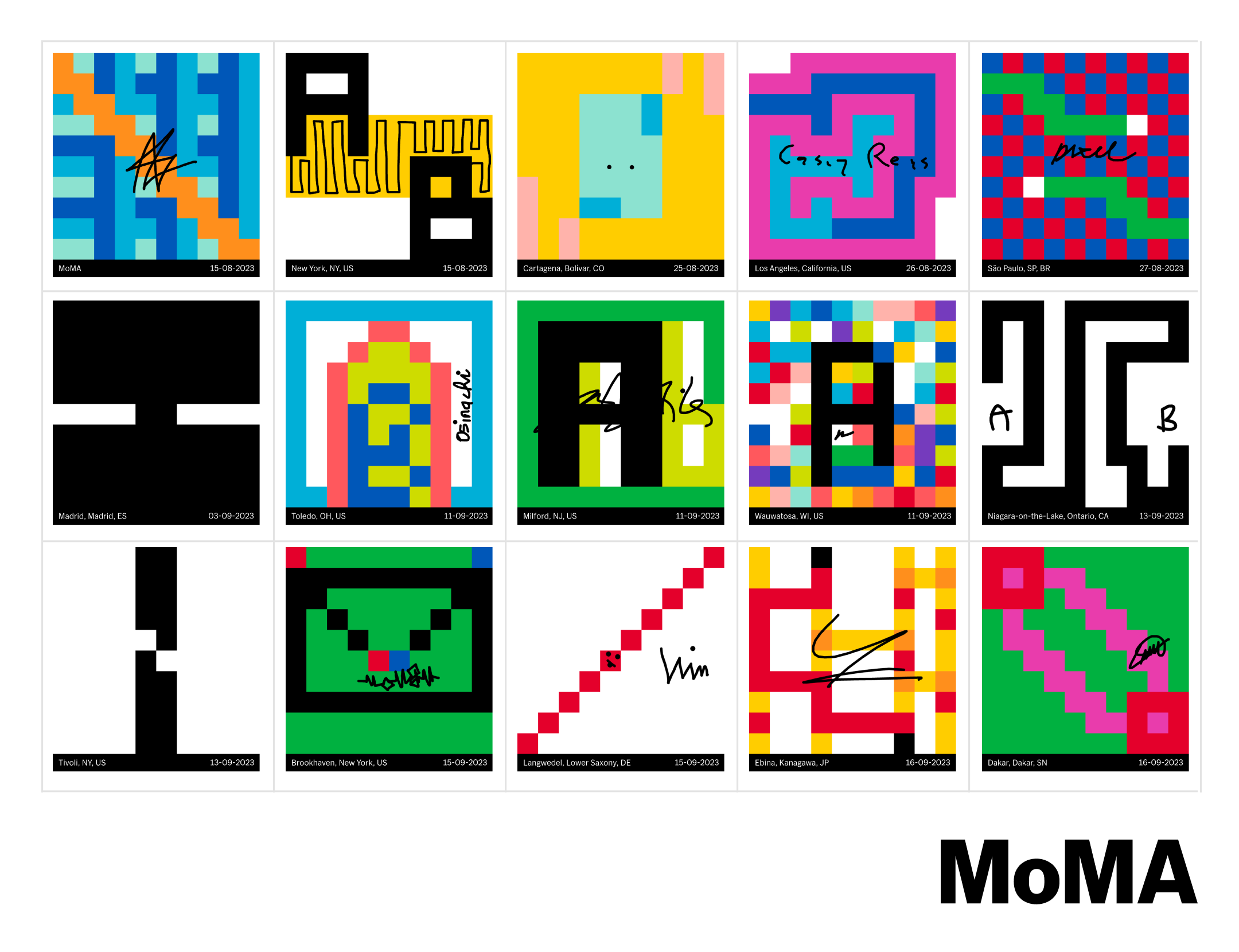

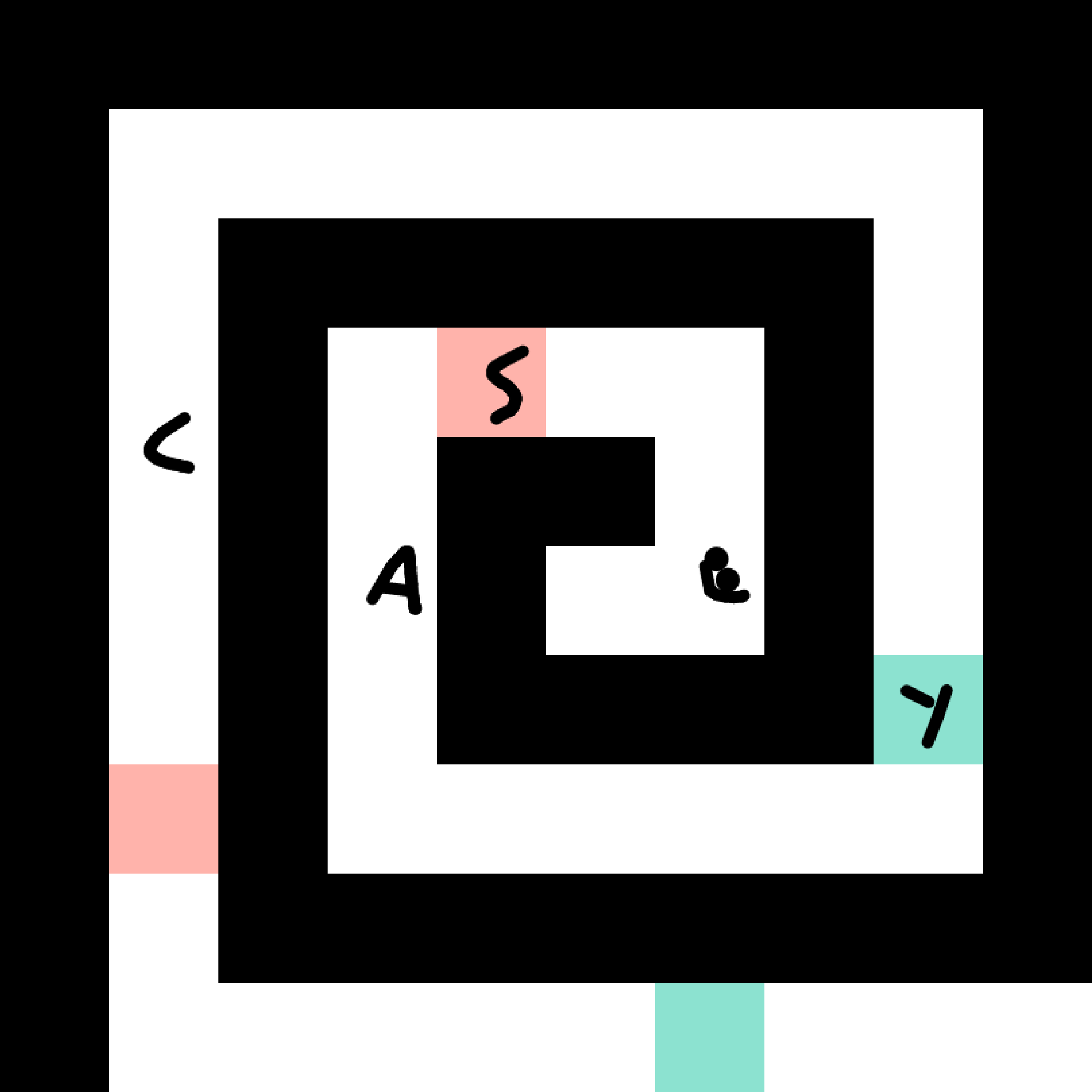

The key strength of MoMA Postcard is that it’s designed in a subversive and self-critical way. It’s an anti-NFT NFT project. Whereas most NFT drops are quickly scooped up for resale and wild financial speculation, the release of “First Fifteen” caused some confusion because its digital drawings could not be immediately collected. The fifteen invited artists had been first to play what is essentially a collaborative art-making game designed by MoMA and Autonomy, creator of a digital art wallet. The artists each started with their own 10×10 pixel image and signature, accompanied by a creative prompt—such as “Copy the last pattern and change 49 pixels” or “a path from A to B.” They then passed around the fifteen digital postcards, contributing a pixel drawing in response to each prompt. The NFTs of these postcards are owned by the artists, so it’s up to them whether they’ll ever be offered for sale. It’s not a high-profile NFT drop; it’s more like an interactive audience engagement program put on by a museum education department.

Strong artists are represented among the “First Fifteen” postcards, but their pixel art creations only scratch the surface of what they’ve proven capable of elsewhere. Casey Reas’s prompt “routine inhibition, animal factors” yielded colorful pixel abstractions from his collaborators, but there’s no hint of Reas’s vast work in video and generative art. Only a short bio on MoMA’s website informs us that he cofounded both Processing Foundation and Feral File, and is responsible for educating and exhibiting countless other digital artists. Sarah Friend comes the closest to exceeding the confines of the postcard project by opting to forgo pixel art altogether with the prompt: “Draw nothing. Forge the signature of the artist after you. If you are last, forge mine.” This wry send-up of cryptographic signatures as marks of authenticity in NFTs recalls her other projects, such as Lifeforms (2021), an NFT series that subverts the financialization of the technology that powers it by requiring that each token be given away within ninety days lest it delete itself.

Collectors and promoters of NFTs—especially those who have stuck around during the current market slump—have a love-hate relationship with institutions like MoMA. On one hand, these advocates make lofty statements about NFTs disrupting the foundations of art creation and ownership to such an extent that “trad” institutions will be irrelevant. On the other hand, they deeply covet the legitimizing imprimatur of the MoMA brand. This was particularly evident in the web3 community’s praise for the recent acquisitions of Refik Anadol’s Unsupervised (2022–23),a pulsing, AI-driven video installation that happens to be an NFT, and Ian Cheng’s 3FACE (2022). But MoMA Postcard is an educational, participatory project that relies on community involvement. While the validating halo of the MoMA brand is present, it can’t easily be used to pump resale prices of digital collectables. Even the trademark artificial scarcity of NFTs is flipped on its head, as there’s no limit on how many postcards the public will be able to eventually produce.

The museum’s website declares that MoMA Postcard is “a chance to experiment with NFTs and blockchain technology in an approachable way.” This emphasis on accessibilityis restated in interviews about the project in NFT-focused outlets. Something about the drive to onboard new audiences to web3 feels a little odd coming from a venerable institution like MoMA. Following the implosion of FTX and several other large crypto exchanges, and the subsequent loss of billions in customer funds, it’s hard to see this onboarding as an anodyne introduction to inevitable new tech. While we were all introduced at various times to novelties like home internet connections, email, smartphones, and social media, the difference with blockchain technology is that the last year and a half has proven that the precarity of crypto can have serious consequences. Markets, the cultural zeitgeist, and government regulation are all casting doubt on the web3 world envisioned by crypto evangelists. So why is a museum so concerned with welcoming everyone to the blockchain?

While the validating halo of the MoMA brand is present, it can’t easily be used to pump resale prices of digital collectables.

In 2023, with NFT hype at a low ebb, the notion that people could buy digital tokens and flip them for profit seems nearly impossible. Even when this strategy worked for a select few, it was never a good idea.MoMA’s push for web3 onboarding risks being interpreted as an invitation to participate in a market bubble that has already popped. The project eschews the market, however, and reveals that its real concern is inviting new audiences to support artists who are using blockchain technology to rethink objecthood, ownership, and creation in a world that is increasingly virtual, placeless, and defined by code. This is worth doing whether the blockchain is truly the paradigm that defines the next era of the internet or not. Digital creation and ownership, and indeed digital existence, are not going away.

It’s clear from the wider work of Reas, Friend, and others that artists who use the blockchain are at their best when they create not only images, but systems that question the fundamentals of art creation and exchange. What is an object? What does it mean to own something? How can the relationships between artist, collector, viewer, and institution be completely reprogrammed? Blockchain technology has the potential to build on the foundations of conceptual art to reopen these questions in fresh ways. MoMA Postcard, as demonstrated in “First Fifteen,” is a clever game. Its value lies less in the limited work of ambitious artists working within its restrictive parameters than in its proposal of a system hinting at the possibilities of collaborative, networked art creation.

Kevin Buist is a critic, curator, and filmmaker living in Grand Rapids, Michigan.