Holographic Media

Media is no longer linear. Legacy outlets fade into noise, and communities have become filters through which all platforms are accessed.

According to artist and activist Gregory Sholette, the art world operates on the backs of thousands of failed artists. The people whose work isn’t validated by institutions end up staffing them as administrators, educators, gift-shop cashiers. Others labor in the studios of art stars, fabricating pieces to be displayed in museums. The art world produces value by restricting recognition and success to a small minority. “How would the art world manage its system of aesthetic valorization if the seemingly superfluous majority—those excluded as non-professionals as much as those destined to ‘fail’—simply gave up on its system of legitimation?” Sholette asks in his 2011 book Dark Matter, whose title is the term he uses to refer to those anonymous creative masses. Crypto art and the NFT market it helped spawn offer a possible answer to this question.

The art world won’t give away cultural capital easily.

Crypto art comes from dark matter. It is made by thousands of people who studied art, in school or independently, and became proficient with digital imaging tools, perhaps enough to ply their skills in commercial design work. The blockchain-based marketplaces that appeared over the last five years provided them with outlets for creative expression and meaningful connections with peers. Their works were bought, sold, and traded in these networks. To display pieces on these online marketplaces required minting them on the Ethereum blockchain, so they appeared to their audience already financialized. From the beginning, SuperRare, Rarible, and their ilk introduced money to the sharing economy, linking recognition among a peer community to cryptocurrency. The resulting mechanisms of value exploded in the NFT market of 2021, at which point crypto art became impossible for the art world to ignore. In Sholette’s terms, the dark matter got bright.

It’s perverse, I admit, to use the terms of an avowedly leftist writer to describe a thoroughly financialized artistic community. But unfortunately, the answer to the lingering question of Sholette’s book—what would it take for people to reject the art world’s systems of valuation and build their own?—is money. He did speculate about this possibility, imagining in Dark Matter “a Peer-to-Peer (P2P) network of support and direct sales bypassing art dealers, critics, galleries, and curators” and acknowledging that “to some degree this has already begun to take shape via media applications of Web 2.0.” But he qualifies this: “What has not happened is any move towards re-distributing the cultural capital bottled up within the holding company known as high art.”

The art world won’t give away cultural capital easily. When Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5,000 Days (2007–2021) sold for 69 million USD in March 2021, followed a few weeks later by a Pak auction at Sotheby’s netting nearly 17 million USD, the art world’s reaction was visceral rejection. We heard that the art attached to NFTs is puerile, simplistic, nothing more than ugly jpgs and software demos—maybe even dangerous, rife with racist and sexist stereotypes. Some of those critiques have merit, but I suspect they were driven less by aesthetic and moral judgment than by a kind of existential horror. These sales demonstrate that the art world’s monopoly on the mechanisms of producing cultural value is weakening. Astronomical prices could be assigned to works of art without the approving participation of traditional institutions. The critical establishment never cared much for auction-house darlings KAWS and Banksy, but even they have shows in galleries and museums. Whatever your aesthetic preferences are, the success of crypto art and NFTs is a fascinating social phenomenon. It represents the creation of a substantial art ecosystem—where social capital, financial capital, and cultural capital flow and trade—in the absence of institutions.

This absence of institutions easily reads as a rejection of them, especially since the use of crypto reflects a rejection, or at least suspicion, of the institutions of finance. Of course crypto art, like any artistic community, is not a monolith; it comprises artists with varying aspirations and attitudes. Yet many voices in crypto art tend to express a bravado ambivalence: If the museum acknowledged us it would be relevant, but it won’t, so it doesn’t matter. In this environment, the marketplaces have ended up as de facto institutions, and they take on multiple institutional roles: publishing interviews and content to garner more attention for the artists who sell there, posting “leaderboards” highlighting the top sellers as a substitute for organizing exhibitions. But without stable hierarchies, positions in the community are hard to define. Artists assert their affiliation with the community just by showing up: being online, being on Discord and Clubhouse and Twitter. One nascent institution is the Museum of Crypto Art, and the only criterion for its founding collection was that work be minted before December 2020: it memorializes the presence of artists who were there first. The intensified sense of presence couples with an orientation toward the future: we’re all gonna make it. Being together in the here and now holds a promise of a better future, also shared, but always deferred.

Similar social dynamics are described in Viktor Misiano’s essay “Cultural Contradictions: On Tusovka,” which theorizes the situation in Moscow in the 1990s when artists operated in an institutional vacuum. Soviet organizations had collapsed. There was no market to speak of. Galleries and contemporary art centers existed only in an embryonic state. Artists who attracted sufficient attention from international museums and collectors decamped for New York and Cologne. To describe what happened in the remaining absence, Misiano used the term tusovka. Depending on context, this word can be translated as “hangout,” “party,” or “scene,” valences of meaning that make it good for describing an artistic community that perpetuated itself through informal gatherings. He developed a taxonomy for the artistic practices of tusovka based on how they relate to its social rhythms. “Attractive interaction” affirmed and reinforced these rhythms—for Misiano, this simply meant participation in regular activities at squats, studios, and other artist-run spaces. “Catastrophic interaction” involved disruptive behavior at these gatherings: Oleg Kulik would walk on all fours and bark like a dog instead of conversing normally with his peers, and Alexander Brener would verbally and physically attack other artists’ works. “Confidential interaction” intensified the tusovka’s rhythms through seminars and other group activities requiring intentional participation. While in many ways the tusovka of the ’90s was nothing like today’s crypto art scene—no money, not even crypto, no Twitter, no internet—the contours of these two institutionless art worlds are related: in both, conviviality and togetherness take on exaggerated importance, and artists dream of institutional acceptance while declaring it worthless. The types of interaction identified by Misiano can be found in crypto art and NFTs, too. (They exist in the institutional art world as well, but they matter the most at its fringes, among the aspiring and the emerging; once you’ve attained some kind of institutional validation, your affiliation with those institutions produces social and cultural capital for you, and your own presence and activity matters less.)

Attractive interaction in crypto art means participation in online spaces, as well as the act of minting. Putting works on marketplaces encourages others to follow. Artists like Hackatao and Xcopy were early adopters and prolific creators. Robness is another, though his trickster attitude led him to dabble in catastrophic interaction, too. Many of his initial contributions to SuperRare recycled the vaporwave aesthetic popularized on Tumblr in the early 2010s: dolphins, pyramids, palm trees, rendered in juicy jewel tones set on flat grids and planes to make their plump forms pop. It was an art of copying and remixing, of severing an image from its context and juxtaposing it with other unmoored signs. Robness became notorious after he minted 64 Gallon Toter (2020), a photo of a big garbage bin copied from Home Depot’s website, distorted and animated with a few readymade effects from a user-friendly image editing program. Hackatao and other leading artists on SuperRare complained the work wasn’t original—it didn’t have the rareness befitting the marketplace’s ethos. SuperRare kicked Robness off the platform.

Like Robness’s vaporwave works, 64 Gallon Toter was a kind of modified readymade. It could have been what the work represented that rubbed the SuperRare elite the wrong way. The trash bin is a receptacle, an index for trash. The token created by minting is also a kind of receptacle, a holder of a link to the media. 64 Gallon Toter could be a read as a metaphor for crypto art in general, a parodic portrait of a token where the form and content point at each other, laughing. Trash is abundant and low value, not super or rare. The richness of these meanings made the work a meme, spawning spinoffs and imitations in a mini-movement dubbed “trash art.” (The “Taking the Trash Out” exhibition on JPG—an online curatorial platform launched to compensate for institutional absences—offers a handy overview.) 64 Gallon Toter was catastrophic: disruptive enough of the platform’s social dynamics and values to make SuperRare shun Robness.

NFT art sometimes overlaps with contemporary art, but the two are still largely distinct, and both phrases make sense in their use as descriptors of sociocultural phenomena.

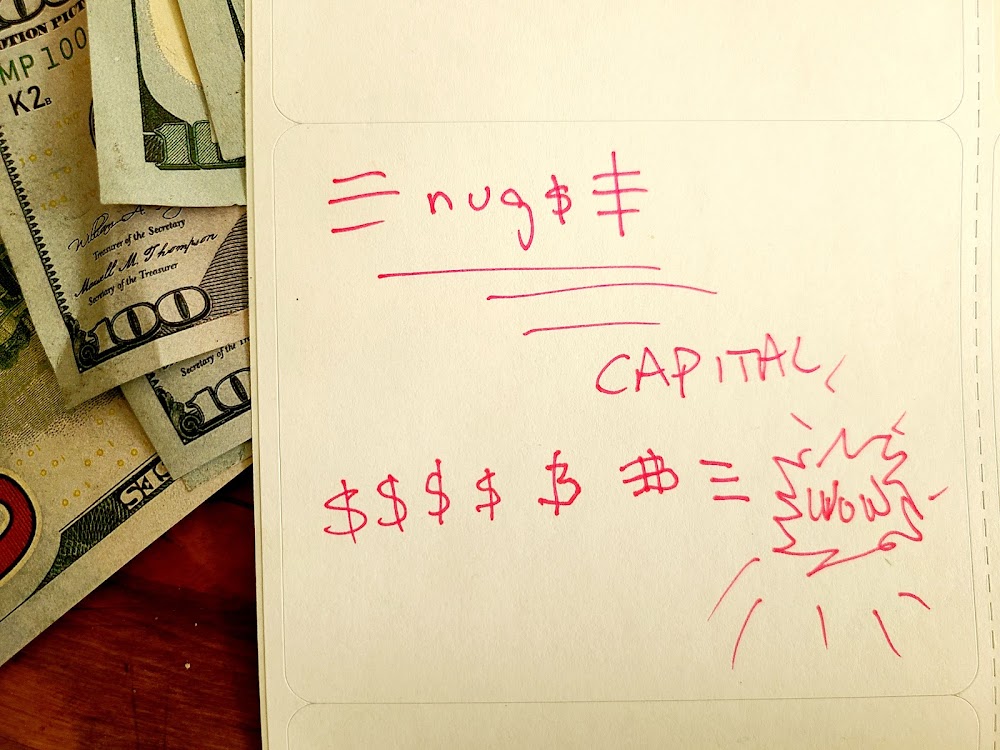

Max Osiris is another artist whose work, like Robness’s, straddles attractive and catastrophic modes. He’s prolific, popping out hundreds of pieces in varying styles: some are psychedelic abstractions inspired by his vision quests, others are collages that include references to—or outright copies of—well-known works of crypto art. His penchant for stealing other artists’ work to make his own also got him booted from SuperRare. He has similarly irked his peers with “low-effort NFTs,” minimal scans of text scribbled on paper and sold, that draw attention to the mechanism of minting. In 2021, when an invitation to Foundation was in high demand, he minted one and auctioned it—an intervention that got him banned from that platform. Like the trash art episode, Osiris’s controversies demonstrate that platforms and communities are contiguous but not identical. His interactions reinforce the scene by testing its limits and questioning its values. For Osiris and Robness, having a recognizable aesthetic doesn’t matter as much as it does for artists like Xcopy or Hackatao, for whom repeated creation reinforces personal branding. Their work, whether prolific minting or disruptive trolling, is ultimately about the social dynamics of the crypto art scene.

It’s important to disentangle crypto art from the NFT market that erupted in 2021. Crypto art was largely a peer-to-peer market; the NFT boom was brought about by speculators and start-ups whose large-scale tokenized projects aspired to repeat the success of CryptoPunks. You could say that attractive interaction matters in the NFT market, but in an accelerated form. Avastars launched in 2020, the first PFP collection intended as such, based on the insight that images from a single collection, used as avatars on Twitter and Discord, could encourage a sense of community, making mutual recognition as fast and frictionless as a crypto transaction. This became more important as the scene continued to expand. The growth also necessitated confidential interaction, the kind of activities that build stronger, more intense connections. Manny404’s Manny’s Game and Sarah Friend’s Off, both launched in 2021, sold NFTs as entries into smaller social circles with their own objectives, distinct from the ones on the gamified bull market.

Crypto art and PFPs, attractive, catastrophic or confidential: all these kinds of work get lumped under the label of “NFT art.” And rightly so. Despite the different ways the many creators active in the space approach their work, they overlap in the type of capital and social networks they use. Denizens of the art world don’t like it when people say “NFT art,” ostensibly because it’s not a medium, which means it doesn’t make the art legible within the frameworks used by the art world. But I assume those same people freely use the phrase “contemporary art,” not to mean any art made in or near the present, but to refer to art that, regardless of medium or style, is associated with a particular set of social, financial, and institutional networks.

NFT art sometimes overlaps with contemporary art, but the two are still largely distinct, and both phrases make sense in their use as descriptors of sociocultural phenomena. NFT art exists separately as an ecosystem that doesn’t depend on the art world’s systems of legitimation. Producing cultural value from scratch is a long process, but some inroads have been made, as demonstrated by the persisting financial value of works by some of the best-known NFT artists despite the current bear market. Those who seek an alternative art world should find some encouragement in NFT art—it is possible to build something else that sustains itself—even if it’s disheartening that financialization is probably necessary to do so in a capitalist world. When the future comes it never looks quite the way you hoped it would; the brightness exposes things you could ignore in the dark.

Brian Droitcour is Outland’s editor-in-chief