Josh Yakov

The former chef went down the crypto rabbit hole during the pandemic and became an expert in generative art.

Nicolas Sassoon, born in France and based in Vancouver, has developed a striking artistic language that draws on the aesthetics of the early 1980s, when personal computers and gaming consoles were first bringing computer graphics into people’s homes. He honed his style while taking part in Computers Club, a group blog founded by Krist Wood and Robert Lorayn in 2008, where member artists contributed large-scale gifs and html pieces. Early in 2021 Sassoon returned to his decade-old output to mint his first NFTs on Foundation. He became an avid collector shortly thereafter. Now his collection numbers hundreds of pieces, many of them acquired at low prices on Hic et Nunc and subsequent Tezos-based marketplaces. In the interview below, Sassoon talks about collecting NFTs as a way both to connect with likeminded artists and to build a more equitable economy for digital art.

When I finally decided to get involved with NFTs, I went back to work I had developed in the early 2010s when I was in Computers Club. It was exciting to revisit that context, and to have an audience of both artists and collectors who want to engage with it and find value in it. But it wasn’t my connections with artists from that group that led me to get involved with NFTs. I had seen other artists, like Sarah Zucker, selling their work as NFTs. Still, I was skeptical. My only entry point was curator Lindsay Howard, who was working at Foundation at the time. The other trigger was talking to my partner, Kerry Doran, who had been involved in different NFT startups. She told me I should pay attention. All these conversations and observations compounded into my decision.

I minted my first work on Foundation in February 2021. I made my first acquisitions two or three weeks after that. I was just excited. As an artist who is really involved with screen-based work and digital works, I found it really compelling to be able to show appreciation for other digital artists through collecting. I felt a lot of gratitude when I started selling my first NFTs, and I wanted to participate and give back. But collecting was a very spontaneous decision at first. There was no master plan.

Before that I traded with other artists. I had been wanting to collect art, but I never really had the budget or the space to store art and conserve it properly. The prospect of collecting digital work in its digital form, without having it be attached to a device, felt really appealing. It would be hosted online and I wouldn’t have to dedicate a screen on my wall to it.

The artist known as p1xelfool helped onboard me on Hic et Nunc back in April 2021. A significant part of my collecting is focused on artists who are exploring aesthetics similar to mine, but taking them in very different directions and using very different processes. p1xelfool is a good example of that. My process is analog. I create everything “by hand.” I don’t code. But p1xelfool does everything by code, using Processing. So it’s interesting to learn about that. Whenever I collect an artist’s work, I do a little research. That’s just as exciting to me as collecting itself.

IX Shells is another artist who works mostly by coding. When I bought her work it was one of the most expensive ones I had acquired. It cost 0.8 ETH. I was scared because it represented a lot of money at the time. Again, my partner Kerry pushed me to collect it. She knew the work was good and IX was going to get somewhere. Afro Netrunner had this code embedded in the work. I spent a couple weeks trying to decipher it. It brought me back to a childlike appreciation of artwork, looking at it and knowing there was a hidden message.

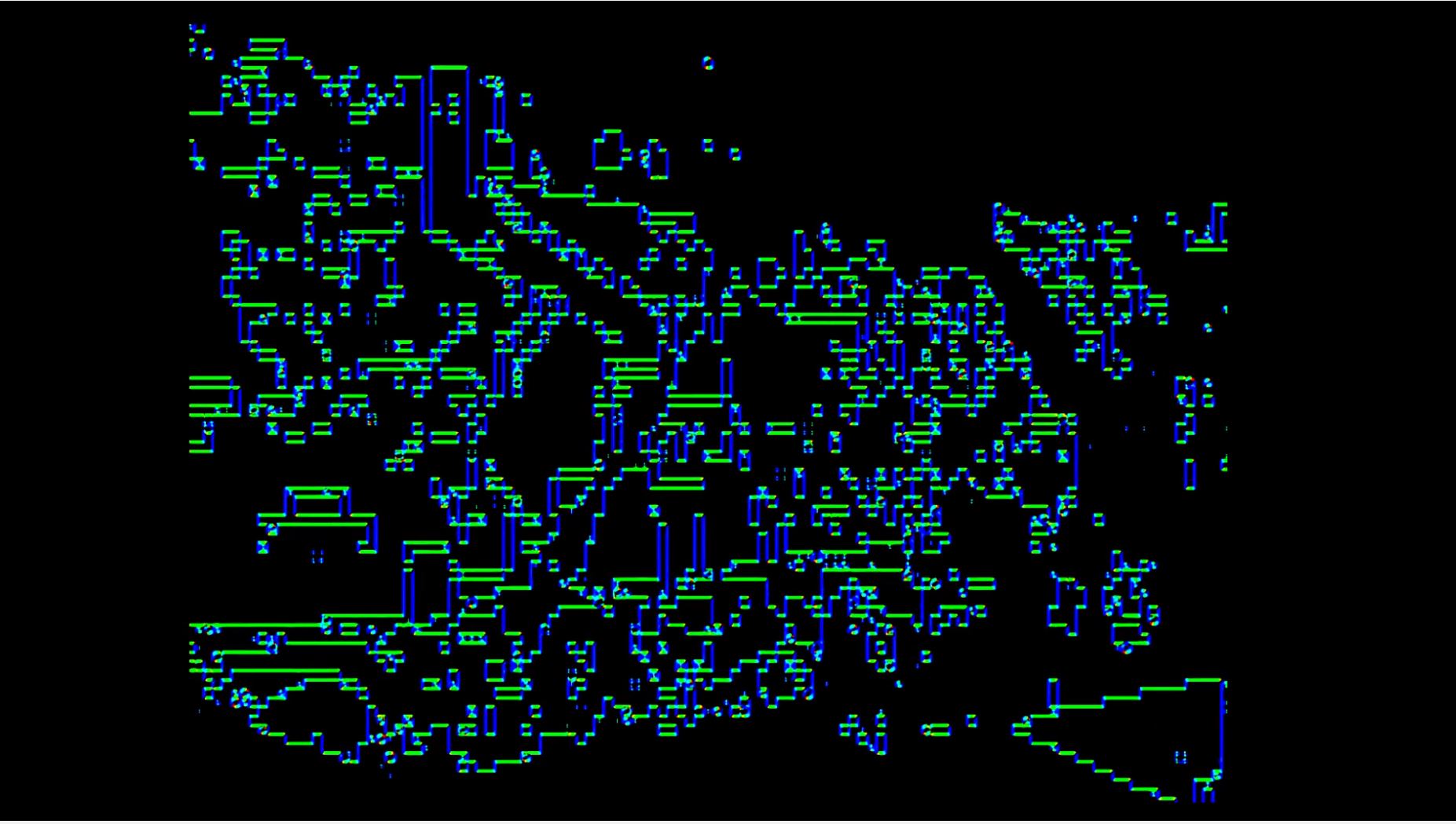

Kim Asendorf is another artist who was really active in the early 2010s, then went under the radar for a few years and came back. I’ve been trying to educate myself about generative art, and Kim’s work is fascinating to me because he works with pixelated patterns almost on a cellular level. There are all these different grids and textures and sort of glitchy elements that are constantly regenerating themselves, but there’s a sense of structure in the chaos. And I love the work on a purely visual level. It brings me back to the work that was popular online in the early 2010s, which had an immediate impact but offered more on the second reading. That’s what I appreciate about Kim’s work. There’s a rhythm and a depth and a richness to all the textural elements.

The gif has become a vessel for so many different things that talking about it as a medium feels really reductive. Like everybody else, I use gifs in chats or on Twitter to convey certain ideas and feelings. Then there are artists who are exploring the gif format, but they bring so many different aesthetics and types of imagery that it feels hard to pinpoint what it means as a medium. I like working with restrictions or restraints, and with gifs you have to be aware of the limitations of the format. You shouldn’t make a file too big because it will slow the browser. When I started working with gifs these factors felt limiting, but then they became exciting because of the potential for formal play. So I collect lots of NFTs that are gifs but it is never a “selling point” for me.

I’ve been in a dialogue with Lorna Mills for at least ten years. I first discovered her work online but I’ve seen several of her exhibitions, and it’s impressive to see her work projected at a very large scale. When you see her work online it’s usually an isolated gif. But in the exhibition space she presents a multitude at different scales in rich compositions. For a show in Toronto in 2012 she painted all the walls black and recessed the screens in the walls—there was a lot of effort put into how to make digital artifacts exist in a space while speaking to their digital nature. It’s really exciting to see her work in the NFT space just for its historical significance. I ended up collecting quite a bit of her work, both on Ethereum and Tezos.

I’ve had a few conversations with Kerim Safa. He and I have a fairly similar approach. He draws everything frame by frame. It’s not generative. So there’s something very tedious and time-consuming about the way he works. He puts out work slowly. His series “Screenweavers” on OBJKT is really beautiful. They’re full-screen animations. I connected with them instantly because they remind me of some of my animated pattern work. As with p1xelfool, I feel a strong connection to the work, but there are all these subtle differences.

I met Kristen Roos last year. We’ve both been living in Vancouver for fourteen years but had no awareness of each other. Kristen has been doing all this historical research on early computer graphics and the different hardware and software used in graphic design from the 1980s onward. Kristen actually uses really old computers—Apple Macintosh, Amiga, IBM, etc.—and has an extensive collection of hardware and software. So aside from his art practice, he is also like a historian in terms of the research he conducts and publishes on his website.

Serious collectors usually take time to decide to collect a work. But with NFTs, you can collect a work in five seconds and then look at another one. A lot of the works in my collection have been bought on a whim while I’m browsing, especially on the Tezos blockchain where the price points are really low. I can collect a dozen works in a day and spend a hundred dollars. This completely changes the concept of collecting, because the price points are so different. The act of collecting is immediate. It’s part of a flux. Some other works in my collection, especially on Ethereum, have involved more research and thinking.

I feel kind of self-conscious being interviewed about collecting because I’m not an experienced collector. I’m happy to talk about how exciting it is to see all this mutual support among artists and how that is an exciting cultural shift. The thing that’s revolutionary about web3 is the monetization of these small gestures, which is making a huge difference for artists. I’m thinking a lot more about the sort of impact that artists collecting other artists have in that space, and the resulting circular economies. That’s the part that really captivates me and I’m trying to understand it better. I want to keep collecting and thinking about my activity in terms of how to show it or how to make it exist beyond where it is at the moment. In the twentieth century there were lot of attempts to redistribute money in the art world that never really succeeded. And suddenly there’s a window of opportunity with NFTs for artists to create circles of mutual support and gain autonomy and agency over their work. And to me collecting is a part of that. So the way I collect is very different from what traditional art world collectors do.

—As told to Brian Droitcour