Personal Daemons

Ian Cheng’s personality test for NFT collectors connects the impulses toward speculation and introspection.

You will probably first encounter Obaa—Miles Peyton’s collection of 512 NFTs, each a unique underwater environment inhabited by a slimy, shapeshifting entity—through the videos posted to the project’s Twitter/X account. There, you’ll learn that everyone, from ASMR e-boys to half-man-half-lobster bodybuilders, is fired up about Obaa’s mysterious powers. Some have harnessed Obaa to their benefit (a Bryan Johnson-esque billionaire biohacker claims that consuming Obaa in green juice has given him an edge that he can’t deny), while others are concerned that Obaa has the potential to destabilize global politics (a spoof CIA leak alleges that some of our nation’s top ranking government officials may already be under its sway).

Riffing on the absurdity of various canonical internet characters and media tropes to insert Obaa into the zeitgeist feels typical of Yeche Lange, the spiritually and functionally internet-native art gallery where Peyton works as a developer and through which he released the project on August 1. (It sold out in hours.) Launched by Milo Conroy, Jared Madere, and anonymous Twitter personality @wretched_worm in 2022, Yeche Lange has mainly showcased art with a kitschy, playful, and deeply online sensibility. While at face value Obaa is a comparatively visually restrained project, its soft, jellyfish-like appearance is something of an anomaly in the generative art canon, which is dominated by angular, geometric forms. It is also an aesthetically and conceptually playful examination of artificial life forms and their potential—to display autonomous behavior, to enter into symbiotic relationships, and to experience mortality.

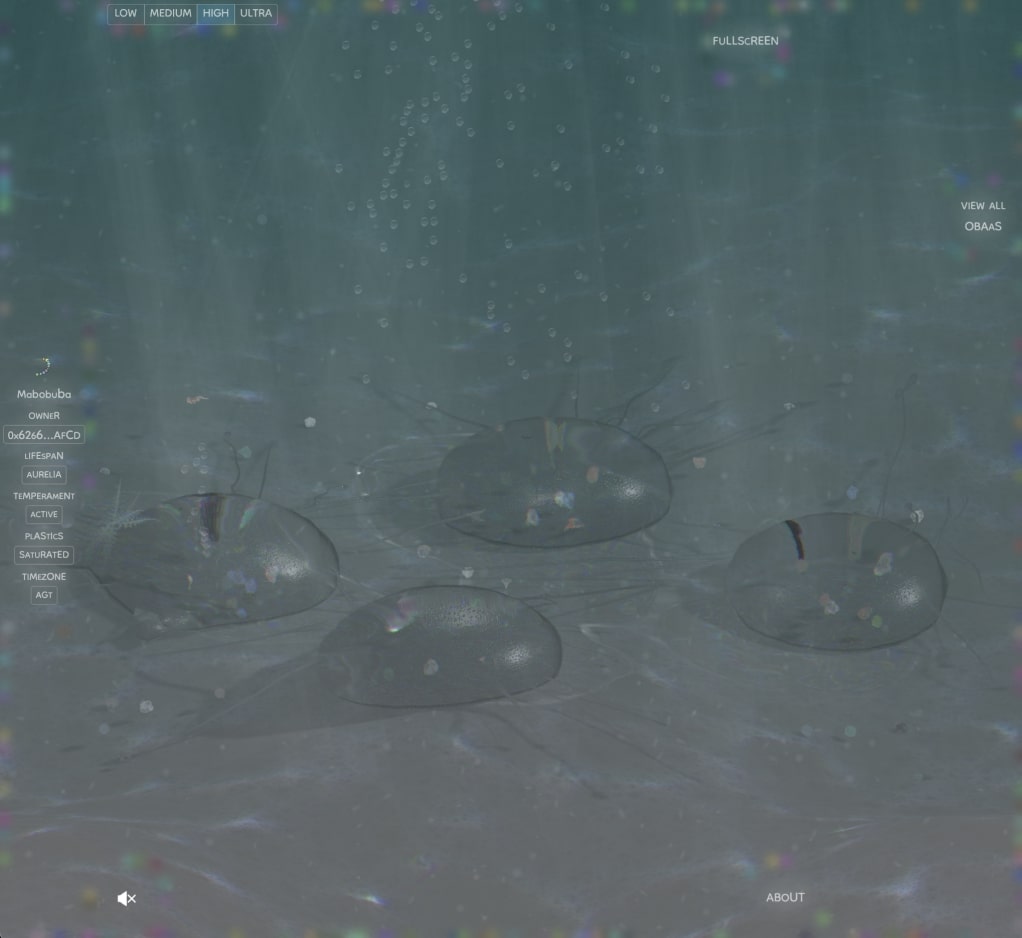

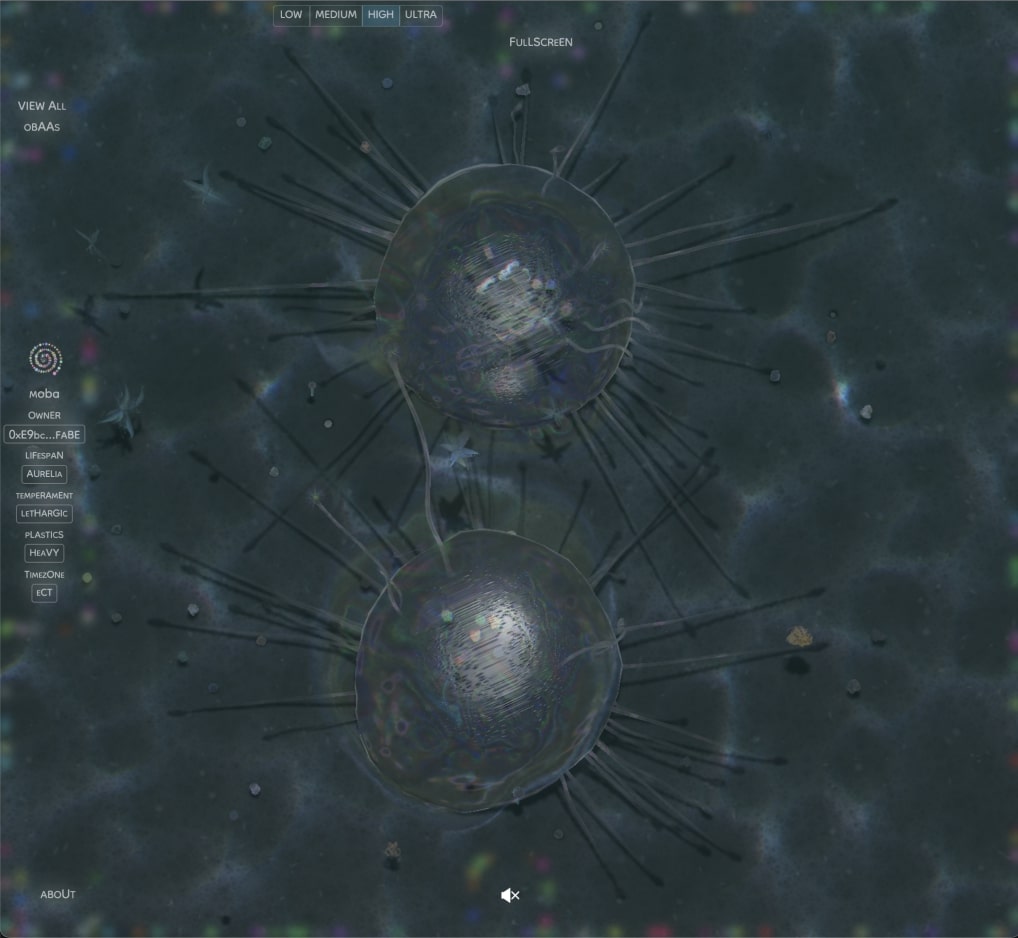

According to the “About” page on the project’s website, Obaa is a “dividual,” or “collective organism.” She lives in a sunlight-dappled, aquatic environment alongside shimmering microplastics and fellow sea creatures, and spends her days dividing and coming back together, absorbing and releasing her co-inhabitants in the process. Each NFT is a unique edition of Obaa, with programmed traits that include a lifespan ranging from months to hundreds of years; a temperament that informs movement patterns, from lethargic to manic; and an individual, vowel-laden name such as Boobbo or Maooaaaa.

Watching Obaa shapeshift is a soothing, meditative experience that evokes playing with silly putty, or watching videos of disembodied hands molding glittery, homemade slime on TikTok and Instagram. ASMR-adjacent slime content reached a fever pitch on social media around 2016, leading to a national shortage of Elmer’s glue (a key ingredient in homemade slime), and a wave of investigative articles trying to figure out why kids and adults alike were suddenly mad about low-tech goo. The joy of playing with—or voyeuristically watching someone else play with—slime is largely attributed to its tactile, sensory nature, which provides a much-needed respite from the noise of the timeline and one’s inner demons.

The project is an aesthetically and conceptually playful examination of artificial life forms and their potential.

Obaa moves without human intervention, making her functionally less like slime and more like the animals in a zoo cam or aquarium. “I wanted to make something that was a display of life that’s not an enclosure,” explained Peyton when we spoke. “Often, you walk into a gallery and see an aquarium and it’s some rare fish that’s been imported from somewhere that’s probably died over the course of the show and they’ve had to replace it. It’s a very Victorian way of dealing with ecology as subject matter.” In Obaa, Peyton has created an entity that mimics the dynamic, unpredictable qualities of life, while avoiding the need to inflict suffering for the consumptive pleasure of a human audience.

In “No life without a membrane,” his 2020 thesis for his MFA in media arts at UCLA, Peyton reconsidered a famous scientific scandal. In 1868, British biologist Thomas Huxley observed autonomous movement while examining a mud sample from the Atlantic seafloor and enthusiastically declared that he had discovered a new organic substance, the primordial slime from which all other life sprang. He named his baby Bathybius Haeckelii and gained the support of much of the scientific community, until it was eventually discovered that Bathybius’ perceived aliveness was merely a reaction between the mud sample and the alcohol that had been used to preserve it. While the incident is widely remembered as a cautionary tale about the risks of unchecked scientific hubris, in his thesis essay, Peyton wondered: “Is the tendency to perceive life in nonliving entities a bad habit to unlearn, or a skill to cultivate?”

He has followed this thread through several artworks that attempt to enchant their human observers by cultivating the simulated appearance of life. In Sunlit Waterneither (2020), Peyton projected sunlight onto a liquid lens to create fleeting water animations; his first NFT project, Porous Trainer (2022), is a collection of 100 spherical membranes, each encapsulating an evolving, branch-like skeleton, periodically permeated by flatworms and other animals in the scene. In February 2023, Peyton presented an earlier version of Obaa in a solo show at Human Resources Gallery in Los Angeles, projecting Obaa onto a large screen.

These projects were inspired by the teachings of biologist Lynn Margulis, who viewed evolution as a symbiotic and cooperative process and rejected competition-based “survival of the fittest” frameworks. Her and Dorion Sagan’s statement (in the 1986 book Microcosmos) that there is “no life without a membrane” informed Obaa’s porous, slippery form, which engulfs and releases microplastics and other creatures as they come into her orbit. Peyton does not view this process as parasitic, but rather as a give-and-take that reflects how entities inevitably adapt based on their surroundings and influences. “Obaa is absorbing all these other creatures, but I didn’t want it to be a predator relationship,” he told me. “It’s more symbiotic and ambiguous: they’re not dying or being consumed, but there is some kind of exchange implied.”

Each Obaa has an expiration date, with a lifespan corresponding with those of various real-life sea organisms, from algae to whales; the respective species’ lifespan paired with the Obaa’s microplastics density content provides an indication of her life expectancy. (After Obaa dies, the NFT itself—as well as the microplastics and generations of other creatures that populate the sea—will remain.) “What interested me about the death mechanic was adding some kind of stakes. Often with artificial life forms you can just restart it over and over again,” said Peyton. Obaa is not a mere Tamagotchi to be coddled, played with and abandoned; she will live and die regardless of human attention. Collectors cannot prevent their Obaa’s eventual death. In some cases, they may not survive long enough to mourn or lay her to rest. The programmed demise of each Obaa is a salient reminder that while technology may not be sentient, it cannot be effectively controlled by human masters.

Obaa is not a mere Tamagotchi to be coddled, played with and abandoned; she will live and die regardless of human attention.

While Obaa’s genesis and lore are significant, Peyton is just as happy for people to simply experience the project as a “weird blob” on their feed. “In the NFT space, I like that there’s sometimes no context when you see something,” he said. “If this same project were to exist in a more sanctioned art space, you would have a wall text telling you it’s about this and this and you have to know these things.” Whether you consider Obaa an elaborate musing on the essence of sentience or just a cute, squishy digital jellyfish, it’s hard not to be moved. After all, we are all porous, fluid beings, waiting to change and be changed by that which enters our orbit.

Tara Kenny is a culture writer based in New York.