Fork Your Society, I want Out

Silicon Valley thought leader Balaji Srinivasan has proposed a revolutionary new form of statecraft, but it’s limited by metaphors of software development.

The default view of painting is that it’s a fundamentally analog practice, a notion that—combined with market forces—has probably contributed to the medium’s rocketing resurgence over the past decade. But painting, while a reassuringly physical offering in lives otherwise turned inescapably virtual, isn’t synonymous with luddism. Its makers have leveraged technological developments since Vermeer and Canaletto composed using camera obscuras, and painting has been entangled with computers, particularly, for some time. For an early instance one might think of Lee Mullican’s mid-’80s Computer Joy works, in which the American painter—then in his sixties—adapted the striated abstract patterns he’d been producing on canvas for a sixteen-color IBM 5170 and a stylus. (The pulsing, trippy, glitched-out results, initially presented onscreen, were released as NFTs in 2021.) By the early 1990s, as personal computers became more commonplace, Albert Oehlen was using a drawing program on a rudimentary Texas Instruments computer to produce digital marks, which he then turned into silkscreens and, in an iconoclastic downgrading of the artist’s touch, intermingled with brushstrokes on canvas. Simultaneously, then-student Laura Owens was already rehearsing her paintings’ color combinations onscreen.

As image-generating software has advanced and democratized, painters have begun using it in composing their work.

Back then, such toggling between pixels and paint was relatively rare. Not anymore, though, and not just among younger artists. Found image deployers such as Luc Tuymans—and his numerous epigones—formerly worked with photographic archives and postcards; now they trawl the Internet for imagery, edit it, paint it, give it gravitas and ambiguity. Christopher Wool’s recent paintings are often based on his own earlier works that he’s photographed, dragged into Photoshop, and manipulated. Wade Guyton, too, composes using word processing and digital editing programs. For all that computer-derived images have folded themselves diversely into painterly aesthetics and logics over the last three decades, though, lately there is something new afoot. As image-generating software has advanced and democratized, painters have begun using it in composing their work, the results operating on a spectrum between scenes intricately designed and lit using 3D modeling programs before being transmuted into paint, and paintings made after the artist has engaged the unpredictability filter of an AI prompt. And while doing so, as we’ll see, they’re increasingly reshaping notions of what constitutes realism in visual art.

In this short timeline, a significant early adopter is Avery Singer, who began working with Google Sketchup soon after graduating from Cooper Union in New York in 2010, using it not—as most artists do—to make mockups of exhibition spaces but to essay witty, blocky figurative vignettes that often comment on lives lived in the art world. (Her newest paintings, on view at Hauser & Wirth London this fall, feature a drunken art student and Singer manqué—this character has recurred throughout her career—roaming Manhattan in the wake of 9/11.) In The Studio Visit (2012), two neo-constructivist figures, artist and guest, sit at a table surrounded by artworks that seem more real than they are. Taking resistance to the artist’s hand a step further than Oehlen, Singer applied such premapped compositions to canvas using grayscale airbrushing, so that her hand literally never touched the work’s surface. More recently, she’s adopted a computer-programmable airbrush—a Japanese-made Michelangelo Art/Robo, usually used for applying logos to vehicles, buildings, etc.—to distance herself even more. Singer’s cockeyed use and addressing of the digital sphere, then, might be seen to go hand in hand with inventive material approaches. Outside of computers being as much a determinative part of her environment as, say, the conventions of the art world (or Instagram), she appears less interested in any kind of commentary on digitality—which would inevitably carbon-date the work as time passed—than in open-mindedly using whatever is to hand, computers included, to get somewhere uncharted in painting.

Emma Webster, too, uses modeling software in her art—primarily Blender and Medium, the latter alongside an Oculus VR headset. She is a landscape painter, but while her compositions are rooted in art-historical landscape formats, the control permitted by computer composition turns everything fluid: perspectives bend and reverse crazily, colors are jacked up into impossible hues. Tech allows Webster to practice extensively, particularly with lighting, before turning her compositions into expressively daubed paintings. But the residue of digital environments in her work also feels purposeful, rhetorical: she’s making, it appears, landscape art for an era of wild, disorienting weather—she lives in California, in wildfire country—and building a practice angled toward someone who’s spent time wandering not in galleries but in the limitless landscapes of video games, from Red Dead Redemption onwards. Her work isn’t just decodable by the cognoscenti (though it certainly nods to Claude and Turner) but also, and on its own echelon of exclusivity, by the massive numbers of people in the gaming community. Which, if you’re at least partly concerned with ecological awareness—as well as hazarding an answer to the question of what landscape art might look like today—feels astute.

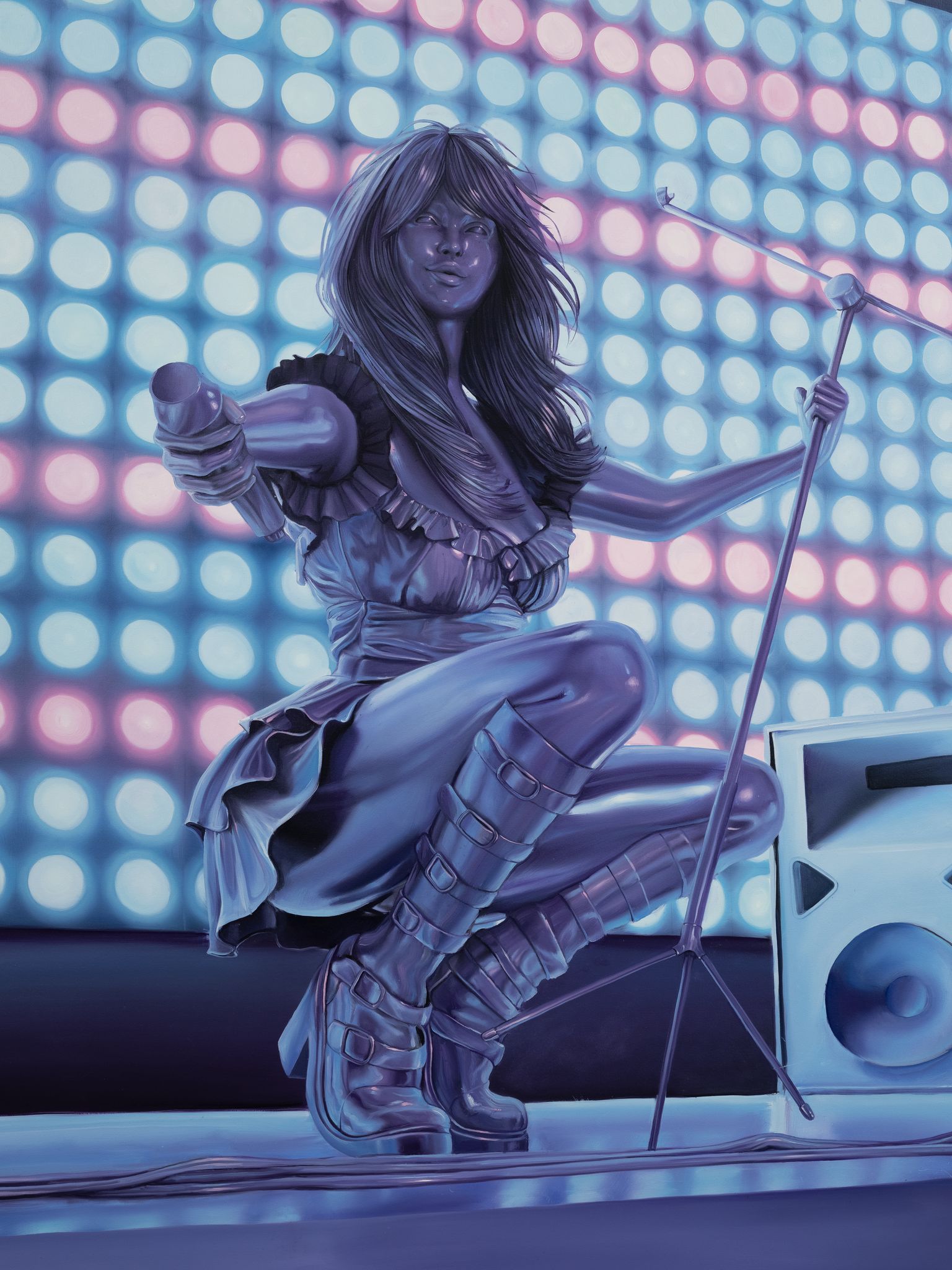

Pragmatism, rather than a breathless embrace of new tools for the sake of novelty, is built into a lot of computer-based painting today. When Emma Stern left New York’s Pratt Institute in 2014 and no longer had access to life models, she began using software typically used to design human figures by game developers and 3D erotica makers. A series of canvases from last year, set in a Waterworld-style future, features pneumatic female pirates—or, thanks to their undisguised footing in digital construction, what feel like glossy figurines of them—climbing masts, swinging cutlasses, gloating over treasure chests, riding a jetski, etc. Stern lights her figures in kitschy shades of peach, gold and diverse blues. The results have an eerie, unreal tone, mobilizing their fabricated origins, that seemingly contrasts this triumphant feminist pirate utopia with the omnidirectional chaos that’s likely to unfold.

In the cases of Singer, Webster and Stern, the plasticity afforded by digital modeling is a throughway to fictional—or at least not-yet-real—worlds; each, in a different way, gets to play God to some degree. Their works, in being representational, also implicitly ask what constitutes realism today, and whether its terms have perhaps vertiginously shifted. Of late, for example, we have figures like philosopher David J. Chalmers suggesting, in his 2022 book Reality+, that if we’re living in a computer simulation and it feels real, we might as well call that reality. Might realism in paintings, in an era when so much of what we see in film and photography is digitally massaged and/or the product of AI, be recast as something like a digital post-photorealism, a painted rendering of a computer image? If reality itself is increasingly fabricated and enmeshed in the digital, might an artistic reflection of that fact itself constitute contemporary realism?

If reality itself is increasingly fabricated and enmeshed in the digital, might an artistic reflection of that fact itself constitute contemporary realism?

The fact we don’t always know how constructed a given image that we see happens to be, meanwhile, is at play in the paintings of Hidetaka Suzuki, who had an online show at Edel Assanti this summer. Hewing somewhat to the Tuymans template, Suzuki finds photographic imagery online, crops it and reduces pictorial information, and paints the result with a gentle lyricism that pushes against—or emphasizes by contrast—his chosen scenarios’ frequent rippling unease and quality of controlled narrative suspension. In Scraping Sound (2023), a veil, or maybe a plastic bag, is either being pulled over or removed from a genderless figure’s face. Suzuki is very good at inexplicably charged punctums—in the aforementioned painting, a dark little niche, like an eyelet, next to the hand; in Untitled-8 (2023), the way the cropped hair of this woman or girl seen from behind gathers tightly, like an expression of personality, at her nape. Under the ontological conditions of Suzuki’s work, this figure may not actually have a face, because the artist sometimes works with found photographs—which may have been doctored before he arrived—and sometimes with AI-generated imagery.

There’s something uncanny about this: an artist applying the same painterly tendresse to depictions of perhaps-invented humans and objects (a tower, a cluster of balloons) as painters historically have to flesh-and-blood figures. When Suzuki paints an image of a shaped box being fitted over a woman’s face—a box that, after a bit of looking, we realize might contain a partial mask of a face, the painting style leveling everything—and titles it True Reality (2022), it’s clear we’re dealing with a wry adept of manifest doubt. And dealing, too, with someone who recognizes that painting’s job has forever been to capture the texture of the present. Our moment is marked both by wraparound digital technology and a related and ever-growing uncertainty about whether a given image has any indexical reality behind it. Painting, evidently, is updatable for the occasion.

Martin Herbert is a writer and critic based in Berlin.