How Does It Make You Feel?

Looking at works by Ian Cheng, Refik Anadol, and Jon Rafman involves a sensory awareness of the AI engaged behind the scenes.

There is a short story by Jorge Luis Borges called “The Lottery in Babylon.” The lottery starts out as most of us would expect it to: players buy tickets, some win money, others do not. But soon the process evolves. Some tickets portend prison or terrible punishment, and some even death, while others can elevate the buyer to godlike status. Everyone in Babylon, rich and poor, demands to play. Access to the “famously delightful, even sensual wheel …. of terror and hope” embodies fate itself.

Today’s crypto art market lends itself to Borgesian extremes. Our version of the Babylonian lottery takes place on platforms like OpenSea, SuperRare, and Objkt; we are buying tickets with pictures on them, waiting for them to yield financial outcomes that are wonderful or horrible or wonderful in their horror. Buying art that appreciates and depreciates rapidly, potentially changing the owner’s material status in the world, is delightful, even when it ends badly, because we, like the citizens of Borges’s Babylon, love the thrill of the bet.

Pak calls Lost Poets a “strategy game,” though they have not disclosed what the rules are, or what the prize will be.

Enter Pak, an artist perhaps most famous for selling a single pixel for 1.36 million USD at Sotheby’s in April. That auction mocked collectors’ preoccupation with rarity and complexity by culminating in the sale of the simplest possible picture element. While Pak works in text, image, and 3D animation, their medium is arguably the structure of the NFT market itself. Lost Poets, Pak’s newest project, exploits the nature of smart contracts and the exchanges they facilitate to produce a participatory conceptual work about how meaning is formed and valued. Pak calls it a “strategy game,” though they have not disclosed what the rules are, or what the prize will be. Neither of those factors have deterred their fans from playing.

Pak is no stranger to Babylon, nor to Borges, whose seminal short story “The Library of Babel” is the primary reference source for Lost Poets. An infinite library of hexagonal rooms containing all known human utterances is the subject of the story, which has been frequent inspiration for digital art already, including that of poet-programmer Jonathan Basile, who recreates it in toto at libraryofbabel.info. Although Pak drops allusions to the library’s structure in Lost Poets—the hexagons used as section markers on the project site, the hexadecimal combinatorics that determine the number of tokens and their traits—their real interest lies in the fictive contents of its books; the project enlists participants to imagine what those contents are.

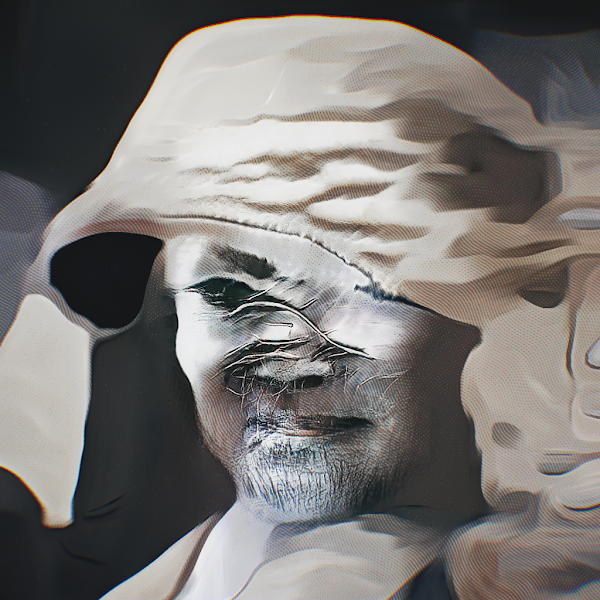

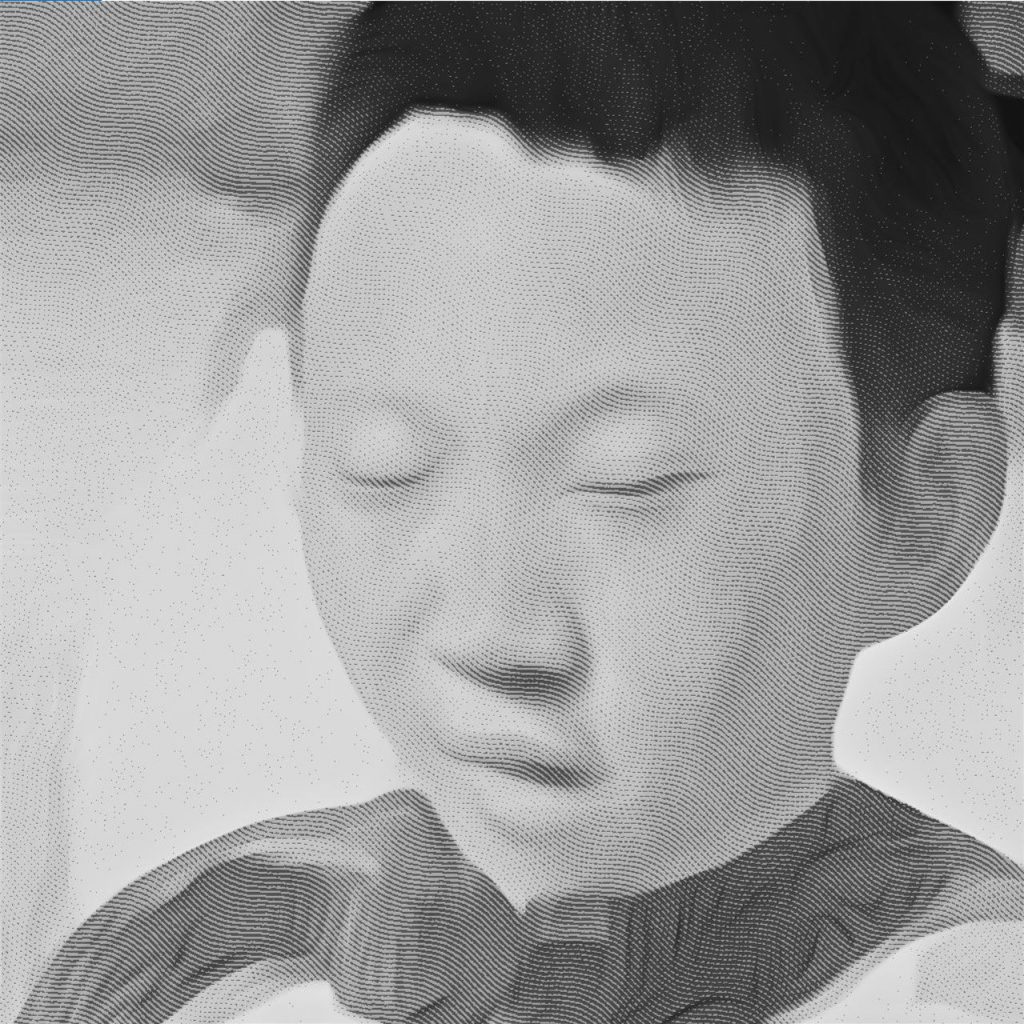

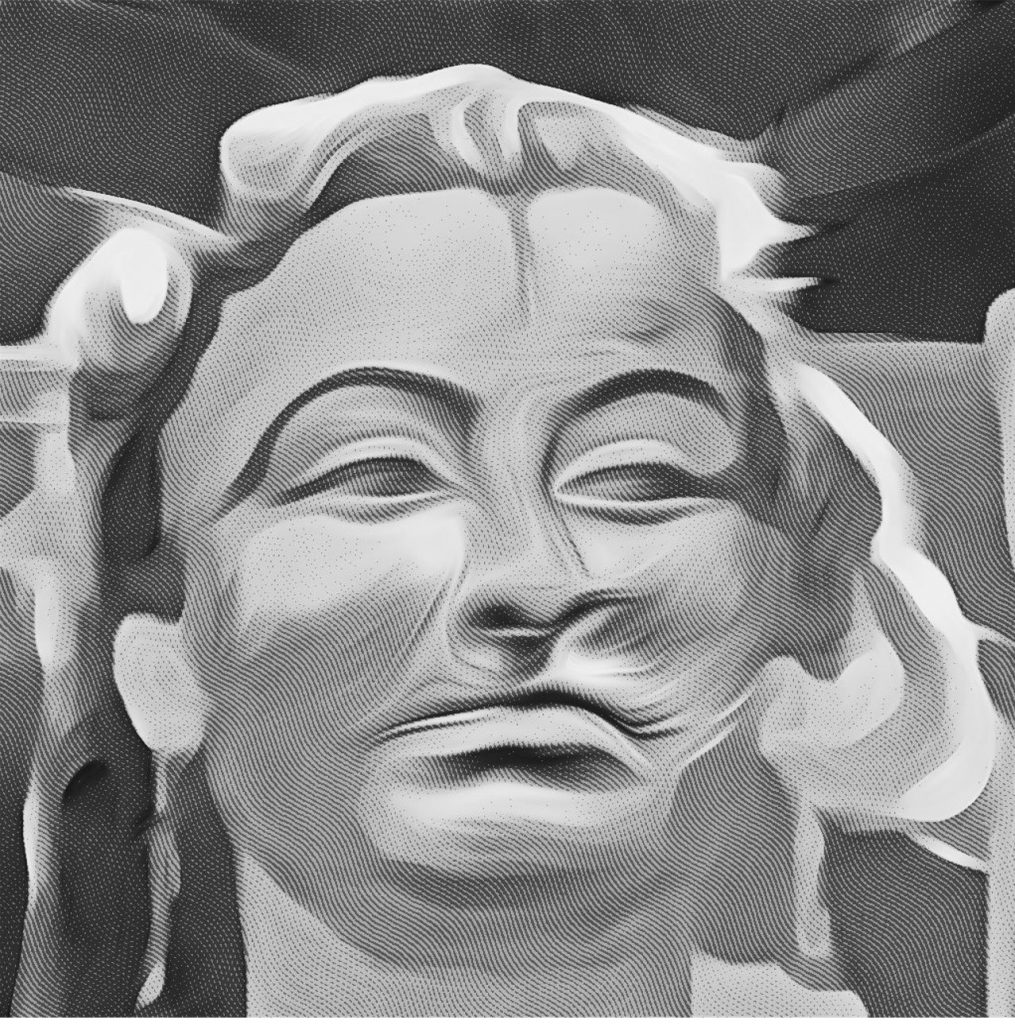

In Act I of Lost Poets, Pak released 65,536 Pages—tokens that allowed buyers to enter the project, and that enable other actions over its course. (The Pages sold out within two hours on September 3, for a total of 70 million USD.) In Act II, buyers had a two-week window to use their Pages to claim Poets, unique NFTs represented by AI-generated portraits riddled with engraving lines to suggest age. Their tubercular palette, heavy in black, red, and gray, evokes a Keatsian eternal melancholy. Pak leans into the tendency of GAN images to appear blurry-edged and almost biologically malformed, attributing this implicitly to the vagaries of time rather than to computer vision’s weakness at determining edges. There are 1,024 Origin Poets, coded to give their holders special permissions, and distributed to participants at random. Their portraits are black-and-white, suggesting pre-color photography, whereas faces of the other Poet resemble ones in Dutch Golden Age portraiture. We’re now in the long Act III of Lost Poets, in which participants can name their Poets and burn more Pages to acquire words that can be used to inscribe poetic utterances in the NFTs’ metadata. Both names and texts affect the rarity of the tokens. Some participants have picked up on classical attributes and chosen names like Demeter or Galatea. Others choose cheekier inflections and more recent referents: Beeple, The Satoshi Nakamoto, Young Mike Piazza (the portrait does bear an amusing resemblance). Still others gave their Poets cryptic monikers like The Orphan or Meta Prophet. In conversations with buyers, I learned that most wrote their own poetry for their Poets rather than searching for readymade text, often imitating Pak’s koan-like public speech. One by the name of Jabulon, shared the text he composed for Meltem, his Origin Poet, via Twitter:

i had a seeming answer to a nonexistent problem which

appearing not to matter held me firmly in its grasp and thus

i felt i might resolve the latter then and for all future time

by taking certain measures in the present tense of now or when

the moment of its next arising brought things to a head but then

the thing that was to happen didn’t happen or appear again

until i had forgotten what it was that was the problem

in the first place or at any time but then it was too late

Just when the Lost Poets were lost is unclear; the stylistic blur of the images, and their anachronistic art history references, suggests a temporal nonspecificity that lends each portrait and the project as a whole a simultaneously haunting and haunted quality. It also implies that when they are bought and named they are found—as if participants in Pak’s project are not just collectors but salvational agents of memory, extending the metaphor of the blockchain as Borgesian library and archetypal archive.

Participants in Pak’s project are not just collectors but salvational agents of memory, extending the metaphor of the blockchain as Borgesian library and archetypal archive.

Besides ETH, the currency of Lost Poets is Pak’s propriety token, $ASH, whose name plays on “burning,” the term for deleting a token from the blockchain. Collectors acquire $ASH by burning Pak’s NFTs, rendering all Pak’s work a kind of meta-work. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust—all that burning slyly suggests that Pak doesn’t think permanence is all it’s cracked up to be. (The project’s tagline Ab aeterno—from eternity—further indicates that Pak is playing with the permanence, much like Borges problematized notions of the stability of meaning.) The five-act structure of Lost Poets functions as a bit of clever salesmanship, with Discord leaderboards for each Act building status and anticipation. But it also underscores the project’s status as a time-based performance. Perhaps it is Pak’s intention for the structure of Lost Poets to follow jo-ha-kyū, the rhythm of the ideal artwork in Japanese poetics, with the planned “twist” (announced on the project’s website) in Act IV functioning like the quickening portion of a Noh play. Or perhaps Pak’s poetic conceit just lends itself to universalizing literary analogy. Anticipating how buyers will behave is part of the artist’s practice. The piece comprises all the actions of the individual buyers, their tweets, the buyers’ tweets and interactions with each other, the material and images produced for the project, and the duration of the transactional phases.

Conceptual art, particularly durational and referential conceptual art, rarely draws blockbuster crowds to traditional art venues, especially in the demographic of Pak’s fans: young, tech-inclined, mostly male, and—crucially—looking to spend immediately at a high price point for access. But for Pak’s buyers, the difficulty of the work seems to a selling point rather than an impediment, as they endlessly speculate about the artist’s next moves in posts to the project’s Discord and on Twitter. In making conceptual art collective, and requiring a substantial financial buy-in to participate, Pak renders the genre sexy, exciting, and somehow new to viewers-owners, who then willingly create community around the work themselves.

Pak’s art relies on the financial transaction as a primary factor of both engagement with and production of the work.

Currently, 0.35 ETH is about 1,580 USD. Although anyone can watch Lost Poets unfold for free from the outside, this floor—however low it is relative to the price of paintings and sculptures—is still quite high for most people. Could a public Pak work be purchased by a museum or other institution to allow free access to this participation-as-experience? Would the work be as interesting without the stakes of a lottery? Pak’s art relies on the financial transaction as a primary factor of both engagement with and production of the work. Modern museum culture is grounded in free or low-cost access to art, but Pak works in a new model, one always and ineluctably rooted in capital as it generates investment from viewers-owners, rather than donors and board members. This is a kind of Borgesian paradox in itself; making the work free to audiences might inextricably change or void its meaning.

Having secured ample seed funding, Pak is now comfortably entering the middle stage of their artistic career. It is my hope as a critic that their commitment to conceptual difficulty accelerates and expands even beyond this promising work. The significance of conceptual projects like Lost Poets informs the success of the medium as a whole, by pushing the bounds of what art can do with NFTs. Pak’s allusive gestures toward rarity and the nature of language haven’t yielded a payoff yet, as the project is still only mid-run; its conclusion may imply new connections between reading and writing, buying and selling. These explorations of the relationships between language, finance, and infinities could take another Borgesian turn. I can only suggest that the players of the lottery keep buying tickets.

A.V. Marraccini is a critic and art historian living in London.