The Treachery of Images

Images have always tempted people to produce more of them. Generative AI ushers in the ultimate freedom of the image from human agency.

“The information about the artwork is actually the most important thing about it,” McKenzie Wark writes in her essay “My Collectible Ass.” “What establishes the value of the work is that people talk about it, write about it, circulate (unauthorized) pictures of it. The more it circulates, the more value it has.” Wark’s text was published in 2017, years before NFTs had gained traction and saturated the context for these ideas. This particular fragment surfaced during a conversation I had with Mexican artist Alejandro Cartagena about the two NFT platforms he cofounded, Fellowship and Obscura. Wark’s ideas supported one of Cartagena’s key arguments: that NFTs are 50 percent information. Normally, information about an artwork accumulates after the work leaves the artist’s studio, but NFTs offer a different possibility: artists can use a smart contract’s metadata to reveal secrets, establish provenance, point to variations, iterations, and predecessors, identify influences and associations, and acknowledge sources of support. After our conversation, however, I was left with the question: how do different degrees of visibility or circulation affect the value of an NFT?

The two NFT gambits Cartagena is involved in have different goals: Fellowship collects and Obscura commissions. Both are focused on photography, and both were established in the last six months. Cartagena cites reading Wark’s essay as a moment of awakening. It led him to take NFTs seriously and got him thinking about the photographs that circulate online and in histories of art. “Will these images also carry some of their circulation value into the space of NFTs?” he wondered. “Can we build a bridge between the digital and the historical, a connection to the two-hundred–year history of photography?”

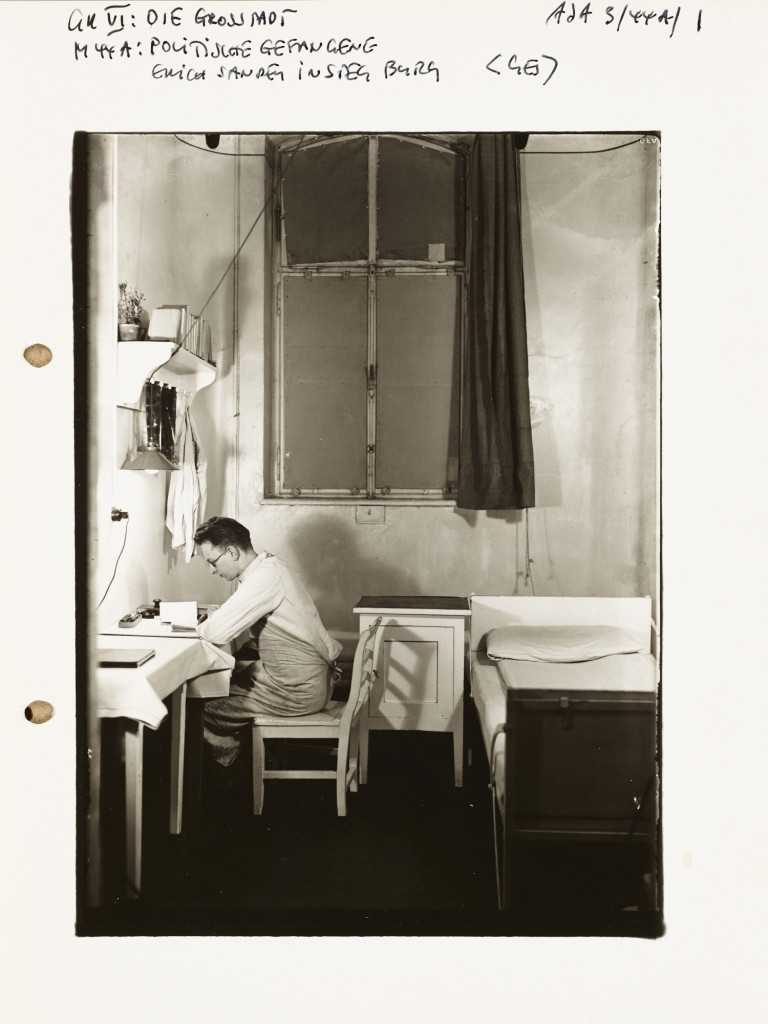

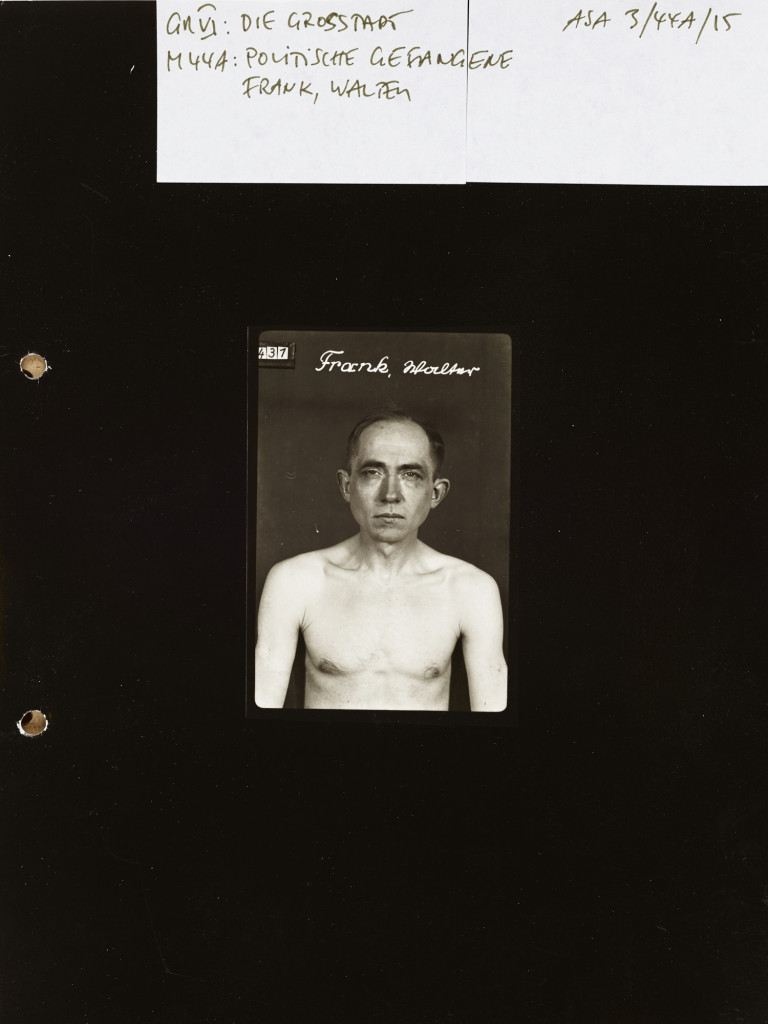

Late last year Fellowship began collecting and distributing NFTs by some of the most iconic photographers of the twentieth century, but in unusual ways. An example is the epic drop of ten thousand images from the August Sander Archive in February. Many of these photographs had never been seen, and most include annotations, dates, and archival notes in the margins. A prolific German photographer of the early twentieth century, Sander is a key historical reference for conceptual documentary image-makers, and is perhaps best known for taking intimate portraits of people working, from a range of social and economic classes, across all occupations, in a project spanning decades. Sixty images from the project were published in the book Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time) in 1929. Fellowship, which Cartagena runs with investor Neil Hutchinson and photographer Chadwick Tyler, dropped the “Fellowship 10k” collection for just twelve hours, from midnight to noon. Buyers paid gas fees, but otherwise all ten thousand NFTs were free. The smart contract stipulated a 7.5 percent resale royalty, with proceeds going to the August Sander Archive and Fellowship. In the first three weeks, the collection generated more than 400 ETH in sales. The goal was to activate the archive, to circulate these images, and to invite people to get to know this photographer and his work. Now more than three thousand collectors have a stake in Sanders’s legacy.

***

“Paradoxically, an object whose image is very widely spread is a rare object, in the sense that few objects have their images spread widely,” writes Wark. “This can be exploited to create value in art objects that are not in the traditional sense rare and singular. The future of collecting may be less in owning the thing that nobody else has, and more in owning the thing that everybody else has.” Wark’s prediction could be a persuasive argument for many of those reluctant to wade into the NFT pond, museums included. During our conversation, Cartagena and I debated whether museums would someday assess an artwork’s circulation as part of their digital collection criteria. Certainly Sanders’s work already has a high spread quotient, despite Nazi censorship during World War II. But does the duration of the spread also matter? Aren’t we bumping up against the myth of the timeless artwork here? History is beset with entropic forces, and survival depends on someone caring in the present—a protest against forgetting. How will NFTs figure in the historical record? Do they mark the beginning of a new period of digital art, or will they become trivial antiques like the ViewMaster 3D?

History is beset with entropic forces, and survival depends on someone caring in the present—a protest against forgetting.

Obscura, the name of Cartagena’s second initiative, references the camera obscura—the pinhole- size discovery that led to the invention of the modern camera. Since January, Obscura has been quietly commissioning NFTs by dozens of photographers. At their inception, they established a partnership with the legendary photography agency Magnum, founded in 1947 by a consortium of photographers that included Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Cartagena and his cofounders—two NFT collectors and DAO enthusiasts, Tony Herrera and Cooper Ray, who is also a photographer—see Magnum as a kind of proto-DAO, a decentralized network of image-makers. While mutually beneficial arrangements like this aren’t new, I’d like to think that productive partnerships such as this might precipitate new collaborations across continents and generations, even setting the stage for multi-institutional DAOs.

Obscura’s upcoming project, “The World Today,” is a large-scale commission inviting 138 photographers from 91 countries to capture one hundred images each over the course of six weeks. Billed as “a visual time stamp of the 21st century,” it will feature 13,800 images altogether, the largest photography commission ever. It’s also an “ode” to Edward Steichen’s “The Family of Man,” one of the most widely seen and circulated photography exhibitions in history. More than 7.5 million people saw the show over the course of its ten-year tour following its 1955 debut at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and its catalogue sold more than 5 million copies. The art world is reluctant to celebrate quantitative home runs like “The Family of Man.” In the last six decades, dozens of critics have attacked it as everything from an overblown Life magazine photo-essay to an act of aesthetic colonialism, yet it remains a landmark.

Steichen’s utopian exhibition globalized Sanders’s Face of Our Time, expanding its scope to include all aspects of human behavior and experience and presenting a vision of the global village at its best and (occasionally) worst. Sixty-seven years later, “The World Today” goes even farther by including “cities, towns, farms, landscapes, communities, people and events.” By comparison, “The Family of Man” featured only black-and-white portraits of men, women, and children, with the solitary exception of an eight- foot-tall color transparency of a mushroom cloud—the threat looming over humanity.

Photography was born of technology and has continued to develop and incorporate new tools over the last two centuries.

Perhaps the most notable difference between “The Family of Man” and “The World Today” is in the order and style of curatorial effort. For “The World Today,” a large team of curators will parse, select, narrate, and sequence images in the reservoir generated by the commission, but only after the entirety is assembled and made public. Steichen, who was also a prominent photographer, winnowed down the pool of submissions to arrive at 503 images presented to the public (filtered through the eyes and values of a middle-aged white man in the 1950s) in a quasi-theatrical sequence that employed inventive display techniques. “The World Today” will offer multiple online pathways through the totality, but with “The Family of Man” there was and will only ever be just one, and it is permanently enshrined in Luxembourg. Can Obscura re-create the excitement around one of the most widely circulated exhibitions in history? Will the echo of “The Family of Man” resonate in the NFT space?

What all these endeavors—Magnum, Fellowship, Obscura, even “The Family of Man”—have in common is that they’re organized by photographers to present photography. Though it is less obvious in retrospect, Steichen’s exhibition was arguing for photography’s place among the high arts. Today Obscura is arguing that NFTs are not just a viable market mechanism, but also have rich cultural dimensions. Photography was born of technology and has continued to develop and incorporate new tools over the last two centuries. It should come as no surprise that photographers would take up NFTs with a spirit of ambition and experimentation.

Joseph del Pesco is a curator, writer, and graphic designer. He serves as international director of Kadist, a contemporary art organization with outposts in Paris and San Francisco.