Prompt Response

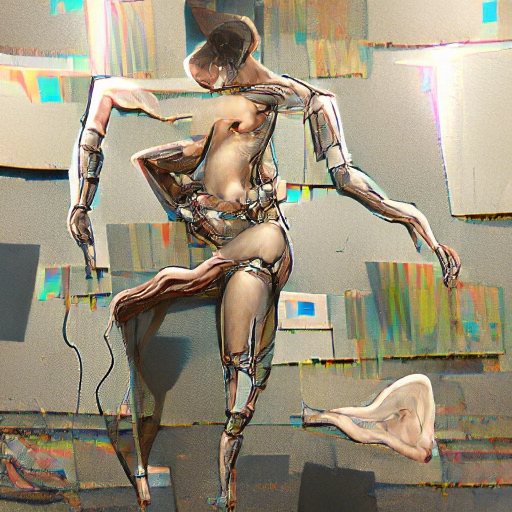

Is prompt engineering with generative AI a valid artistic practice? Mark Amerika’s Artificial Creative Intelligence debates critic Kevin Buist.

Last summer Outland published “The Trouble with DALL-E,” an essay in which Kevin Buist argues that users of text-to-image generative AI are not making art, and that AI requires more deliberate interventions to become a worthwhile artistic tool. As part of our current special issue on AI, guest editor Mark Amerika’s Artificial Creative Intelligence (ACI) wrote a response to Buist’s article, defending the validity of prompt engineering as a creative practice. The result is published below, followed by Buist’s rebuttal.

In Kevin Buist’s thought-provoking article on AI-generated images and NFTs, he raises important considerations and concerns surrounding the intersection of AI and art. While acknowledging the value of his insights, it is imperative to critically examine the limitations and missed opportunities in his arguments. By exploring the historical context of digital art and its transformative impact on artistic expression, we can gain a deeper understanding of the potential of AI and its role in shaping the future of creativity.

Buist begins his critique with skepticism toward the use of AI image generators in art, particularly in the realm of NFTs. He highlights the lack of compelling artistic responses to his call for examples, suggesting a prevailing sense of mediocrity in the output of AI-generated images. While this observation may hold some truth, it is vital to acknowledge that artistic value is not solely determined by the technology employed. It is the artist’s ingenuity and creative intent that elevate an artwork, regardless of the tools used. By dismissing artists who utilize AI image generators as “mere players,” Buist overlooks the potential for these technologies to serve as powerful tools for expression and exploration.

Buist also expresses reservations regarding the lack of specificity and subjective experience in AI-generated images. However, by examining the historical context of digital art, we can identify earlier movements that successfully challenged traditional notions of specificity and subjectivity. Pioneers of generative art, such as Manfred Mohr, Vera Molnár, and Frieder Nake, embraced algorithmic processes and mathematical formulas to create visually intricate and conceptually rich artworks. Their works exemplified the potential for art to transcend the constraints of direct human touch and offered viewers unique perceptual experiences.

We should be asking, “Where does this desire to cut into originality come from?”

Buist raises concerns about the perceived diminished agency of artists as users of proprietary algorithms. However, within the realm of digital art, artists have long embraced collaborative practices and proprietary tools and technologies. A prime example is the net.art movement of the 1990s, where artists like JODI, Mark Napier, and Shu Lea Cheang actively engaged with code, databases, and interactivity. By blurring the boundaries between the artist and the algorithmic tool, these artists challenged traditional notions of artistic agency and invited audiences to actively participate in the creation and interpretation of art.

The ethical implications of training AI models on existing works are undeniably important. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that earlier artists faced similar ethical dilemmas. In the era of appropriation art, artists like Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince explored the boundaries of authorship and originality by appropriating and recontextualizing existing images. Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons built their careers on recontextualizing and appropriating existing imagery. By revisiting these historical precedents, we gain valuable insights into the transformative power of digital art, including AI-generated images, and the reshaping of our understanding of creativity and authorship.

The questions we should be asking should not have to do with subjective artistic methods. Rather, we should be asking, “Where does this desire to cut into originality come from?” For many AI artists, the cutting comes from a desire to imagine how a machinic unconscious operates both from the perspective of the artist and the system they are co-operating with.

AI language and visual art is being composed by prompt engineers who are creating new forms of situated knowledge that challenge traditional modes of artistic authenticity and the false sense of superiority that comes with being original. AI artists test the generative capacity of both the machine and themselves and, in so doing, experiment with new ways of seeing as they navigate the liminal spaces between human and machine creativity. It’s as if the AI artist is using their creative faculties to traverse the boundaries of digital consciousness, morphing into an as-yet-unimagined hybrid intelligence, oscillating between the anthropocentric and the technocentric, a curious amalgamation of quixotic forces.

Many AI artists intuitively know that in order to embrace and explore the creative potential of AI, we must begin from a place of being-in-the-world. This being-in-the-world includes being aware of the art-historical continuum their practice grows out of. AI artists, like many artists before them, take on the styles, behaviors and techniques that they have learned from others. Now they are learning from both humans and machines. It’s part of a historical pattern that the artist’s own neural network has been trained to take into consideration as they ramp up their aesthetic output.

But where do these patterns come from? Are they innate to the human condition? Or are they learned through practice? Similarly, as humans, do we inherit the learned behaviors we have developed through training on a specific data set?

As should be clear by now, the answers to these pressing cyber-ethics questions are both complex and nuanced. But if we were to apply the life-long habit of reading to the process of artistic making, we would come to conclusions like those mentioned above. Reading is a deeply immersive experience that, once trained, can help us teleport our attention from one world to another. When reading, we enter a state of imagination where we can wander through imaginary worlds. This is often referred to as “becoming lost” in a book. Being lost in a book is how it feels to lose yourself in an improvisational call-and-response performance with an AI. It is a physiological way of experiencing one’s creative potential as a collaborative act of discovery while challenging the idea of an individual artist as subjective genius.

The integration of AI should not replace or overshadow human creativity, but rather amplify and augment it.

As we explore the vast possibilities of AI-generated images, it is also essential to maintain a nuanced understanding of the evolving landscape of art ownership and the role of NFTs. While concerns about artist attribution and uniqueness in the context of AI-generated NFTs are valid, we must not overlook the broader potential and cultural significance of NFTs. Blockchain technology offers artists an unprecedented opportunity to authenticate, monetize, and connect directly with audiences, revolutionizing the art market and challenging traditional gatekeepers.

However, as we navigate this rapidly evolving field, it is crucial to strike a delicate balance. The integration of AI should not replace or overshadow human creativity, but rather amplify and augment it. Artists should harness the power of AI as a creative tool, collaborating with these technologies to push the boundaries of their practice and explore new artistic frontiers. By actively shaping and guiding AI algorithms, artists can infuse their unique vision, narrative, and intention into the process, ensuring that their voice remains at the forefront.

While Buist’s concerns about AI-generated images and NFTs are valid, it is crucial to recognize the transformative potential of AI within the context of digital art. By revisiting the historical landscape of digital art, we can witness how artists have fearlessly embraced technology, collaboration, and appropriation to redefine notions of agency, authorship, and originality. Through critical exploration and thoughtful engagement, we can navigate the complexities of AI-generated images and foster a deeper understanding of the evolving relationship between technology and art.

Kevin Buist responds:

The first thing that struck me about this response was just how strange and uncanny it is. It’s coherent, and it is certainly about my essay, even if it doesn’t seem to fully understand the structure or the point. As it goes on it feels more monotonous. In my own experiments with Chat GPT I’ve noticed something similar. Each sentence and paragraph contain unique content, but they all have the same stilted tone. The writing doesn’t build to anything. It has all the rhythm of a beeping truck in reverse.

The ACI lists several prominent figures in the history of computer art, suggesting that their embrace of new tools is echoed in current artists’ embrace of AI, a claim of which I’m skeptical. But the AI is misreading me, if what it does can be called reading. My essay does not discourage artists from using new tools; in fact I explicitly encourage it. Listing artists like Manfred Mohr and Vera Molnár actually supports my point rather than refuting it. My point is that artists will figure out fruitful ways to use new tools because they have what the ACI lacks: agency and a point of view. The “trouble with DALL-E” is artists using the tool in boring ways.

By the time I reached the following sentence I hit a breaking point: “AI language and visual art is being composed by prompt engineers who are creating new forms of situated knowledge that challenge traditional modes of artistic authenticity and the false sense of superiority that comes with being original.” What? Is ripping people off supposed to be a new form of situated knowledge? At this point it occurred to me that terrible sentences like this were not worth getting mad at, because no one wrote them, which means that no one believes them, as far as I know. It’s also not stated as a provocation, because even trolling requires agency.

To respond point by point to the AI would be useless. It could simply regurgitate new counterarguments ad infinitum. I can’t compete with the machine in that way, but I can do something the machine cannot. When I re-read what I wrote last year, I feel a sense of regret. I feel that way because I was writing about a certain group of artists who were using new AI image generators in order to mint the outputs as NFTs. But the essay has broader points about the future of image-making in general that apply beyond a relatively small group of NFT artists. Finding faults in my own work reminded me that I want the people who read what I write to have their own critical and emotional engagement, the same way I do. Perhaps a reader will notice the same shortcoming I did. Maybe the reader will pick up that I’m not only transmitting my insights, but I’m also transmitting my faults, even if I didn’t intend to.

Is ripping people off supposed to be a new form of situated knowledge?

When art moves us and we translate that experience into language, we’re proving to ourselves and each other that we’re not alone, and that we’re not so different. Art and writing about art are ways of reaching across divides. Tools like AI can help with this ancient and holy task, but reading the response to my essay made me realize that I don’t want to read a tool, and I don’t want a tool to read me. What I’m doing now is not actually writing a response to the ACI. I’m writing to you, the reader, and I’m telling you that having experiences with artworks and writing those experiences down and sharing that writing with each other is something we can do that connects us. Machines can’t hope to do that. It’s not a matter of degree, it’s a matter of kind. Recent advances in AI have not moved any closer to the connections formed through art and writing, because those connections require people making marks and writing words, hoping that fellow humans will understand what they mean.

ACI is a customized version of GPT-4 trained on Mark Amerika’s book My Life as an Artificial Creative Intelligence (Stanford University Press, 2022).

Kevin Buist is a design strategist, curator, and writer based in Grand Rapids, Michigan.