Artist-Centered Cybersecurity

NFT artists have to be constantly alert to the threat of scams and hacks. How can cybersecurity approaches be adjusted to protect the most vulnerable?

The internet has always been a place where people can go incognito. But while Web 2.0 apps become ever more entangled in our “real-world identities,” anonymity and the right to privacy have been established as key features of web3 culture. The concept of cryptocurrency was introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto, whose real name remains unknown, and today the blockchain is a space where artists and collectors can construct a name for themselves anew, unburdened by Google Search results. There are clear and well-documented pros and cons to this. Hidden identities empower criminals, but can also free marginalized people from social expectations and prejudices.

True anonymity would make it almost impossible to judge art in the way we are used to.

The proliferation of pseudonyms on the NFT market—including among the highest-selling artists, like Beeple, Pak, and Xcopy—seems at first glance like a significant difference from the traditional art world. But this turns out to be more of a superficial difference. True anonymity would make it almost impossible to judge art in the way we are used to: without a consistent identity to latch onto, the context of its production becomes meaningless. A painting is almost always valuable because of the name in the signature. NFTs, too, are valuable largely because of who mints them. The artist’s identity is still a key factor in how much someone would be willing to pay for their work, and how it’s treated by critics. Since a handle still serves as a stamp of authorship, what we’re seeing with pseudonyms is far from actual anonymity.

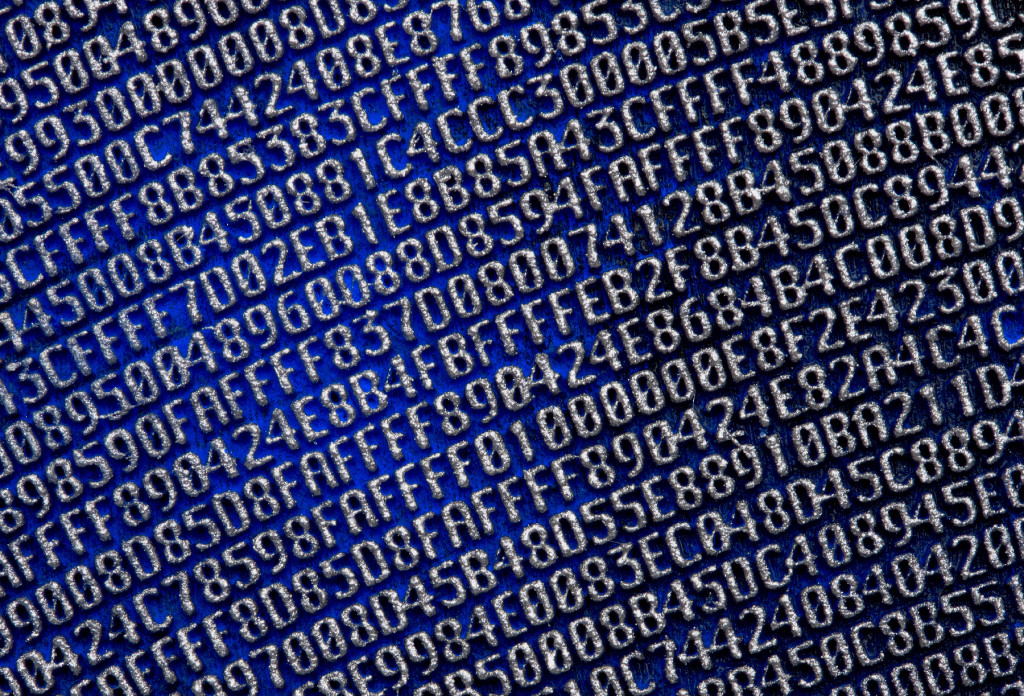

So why do artists working with NFTs adopt pseudonyms? The artist who goes by Robert Alice chose the name as a riff on the notation conventions of cryptography, where Alice and Bob are default names used when discussing communication scenarios. It’s also part of his wider artistic project to chart an intellectual history of blockchain. His best-known work, Portraits of a Mind (2019), is a series of forty paintings and NFTs each bearing 322,048 digits of Nakamoto’s founding code for Bitcoin. How else to commemorate a figure of whom nothing or little else is known? With no further context, the identity behind the pseudonym can only be understood through his work. But for Alice, his own anonymity has turned out to be much looser—closer to that of someone like KAWS, whose real name is equally accessible. (KAWS, of course, has a background in street art, where anonymized monikers create protection from institutions that make this work illegal but—crucially—legible within a system of value.)

It’s almost impossible, after all, to reveal absolutely nothing about oneself online.

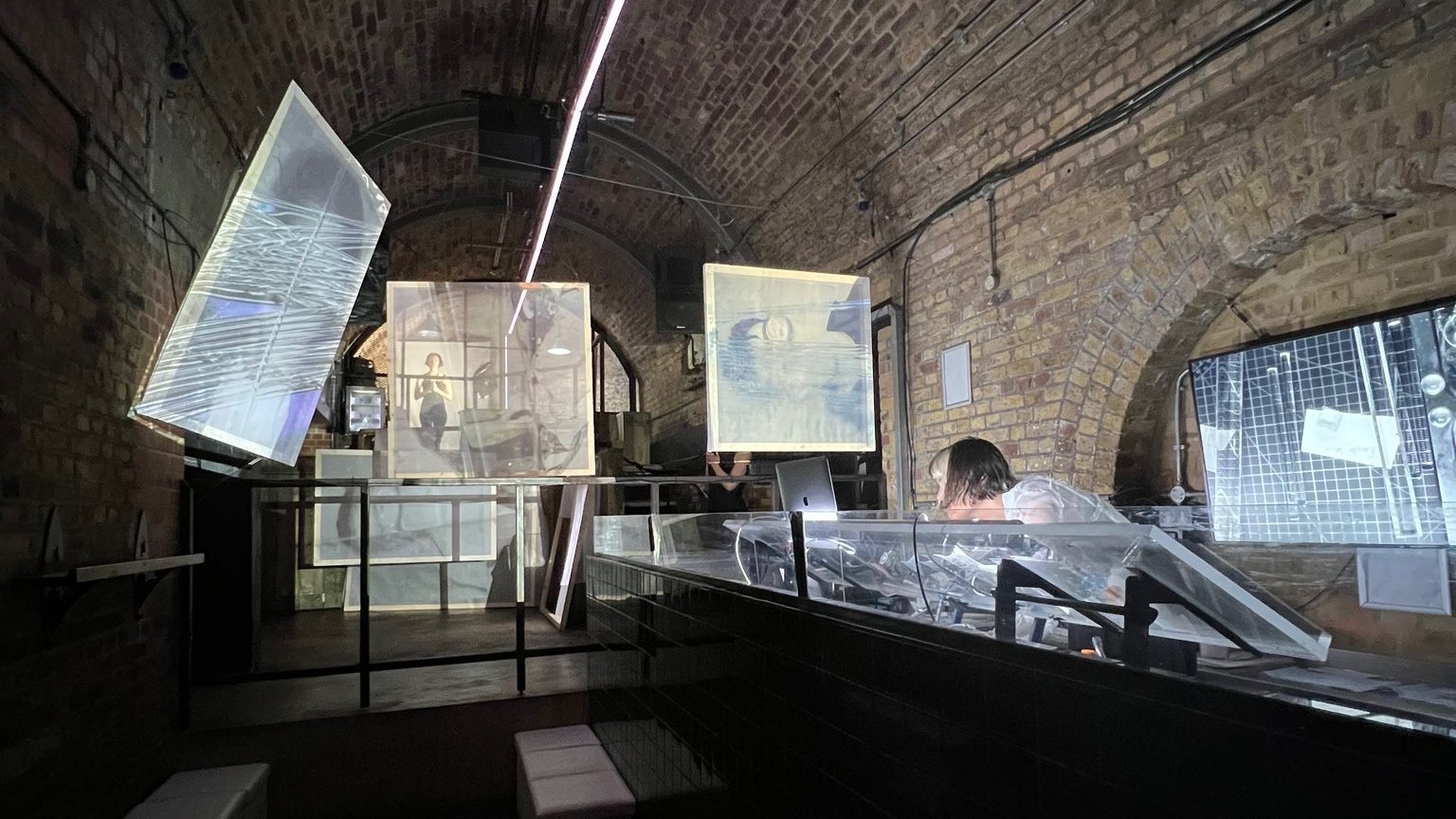

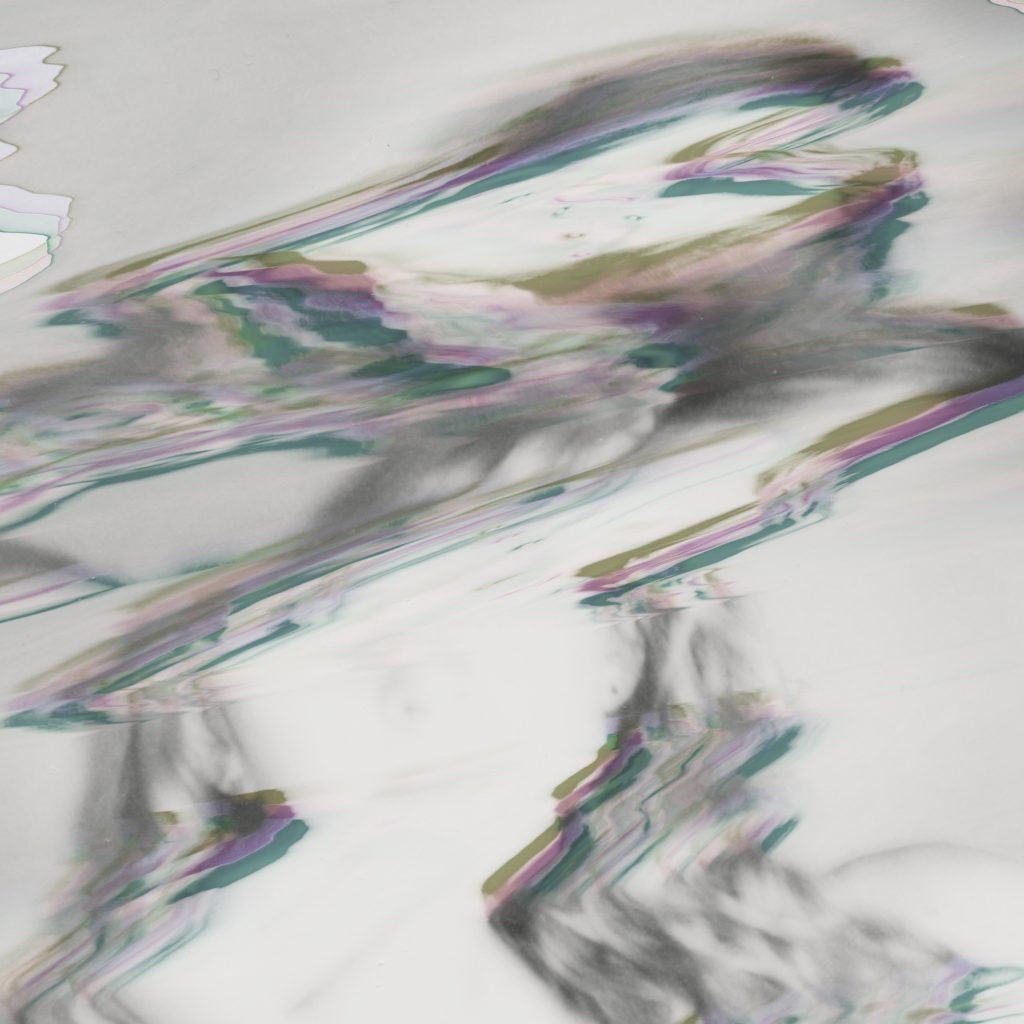

While Robert Alice sounds like it could be a legal name, many other pseudonyms are more succinct, arbitrary, and whimsical: brand-like, one might say. Part of the branding process is adopting a visual identity—hence, perhaps, the popularity of PFP projects. The Privacy Portraits, presented in London this past July by the artist duo Operator (Ania Catherine and Dejha Ti), plays with this desire to be represented differently online, using analog means rather than digital one. Those who wanted to collect the work had to visit the space in person. After providing wallet details, a collector would be assigned two random words, so that the artists could identify them without taking their name. Then collectors were taken through the performance space, and their portrait shot by Catherine, on Polaroid. Collectors were asked to think about something they would like to keep private during the shoot. Ti then manually disfigured these photographs in a process determined by rolling dice. The first number rolled determined the number of rolls to be completed, and each subsequent number designated a way to alter the image: burning or bleaching it, for example, or adding glass and rescanning it. The pair describe this method of portrait-making as algorithmic—using “crypto back-end mechanisms,” but in an organic, physical way. The distorted originals were scanned and either permanently destroyed or kept by the artists—collector’s choice.

The physical aspects of this interactive work reveal some of the limits of pseudonymity. By the artists’ own admission, the system of obscuring identities was leaky: Ti and Catherine recognized some collectors, and some portraits were less obscured than others. It’s almost impossible, after all, to reveal absolutely nothing about oneself online, and even tiny clues can lead sleuths to learn more. When Snoop Dogg claimed that he was the major NFT collector Cozomo de Medici, for example, the internet went wild. But the miniscule amount of information that Cozomo had released about himself was enough to disprove the rumor. In particular, a photo of the NFT collector with the singer Jason Derulo, where Cozomo, even with his face covered by a CryptoPunk, looked nothing like Snoop.

“The author is the ideological figure by which one marks the manner in which we fear the proliferation of meaning,” said Foucault in his 1969 lecture “What is an Author?” An excess of possible identities yields speculation. And this uncertainty is itself a way to create an identity. Pak’s pseudonymity has become part of how we understand their work, through the policed border around their identity. Even so, we surmise, we make judgments. Catherine and Ti feel certain that pseudonyms are the province of male artists, for example. “Our role doesn’t reward women who hide,” Catherine said. “Women almost have to be hyper visible.” Indeed, when original CryptoPunk owner thebeautyandthepunk decided to dox herself, it was to make a statement about gender imbalance. “I really try to keep my real life and my crypto life completely separate,” she told TechCrunch. “But people need to know that women have been [in this space] for a while and we’re not going anywhere.”

In the world of art, names of some kind have always been used to assign continuity, and therefore cultural or economic worth, to works. This is how Renaissance works end up with pseudonymous artists when there isn’t enough documentary evidence to assign authorship—“nonames” like “Master of the Embroidered Foliage,” who is presumed to be responsible for several paintings showing a particular delicacy with leaves. In theory, blockchain transparency links an identity directly to a wallet address, so that art becomes the artist; the collector becomes their collection. The pseudonyms or PFPs or even the public wallet keys—which are unique and can therefore be tracked by “on-chain sleuths”—are never completely anonymous. In a market where identity and value are still so inextricably tied together, no one really wants them to be. These made-up names and faces, then, are more like conjectures, assumed attributes that can be assembled into identities, some considered to be more valuable than others. As observers of these characters, we’re always scrabbling for meaning in the scraps: trying to cobble together something—someone—we know how to value.

Josie Thaddeus-Johns is a freelance art and culture writer living in Berlin.