Ira Greenberg & Ivona Tau

Two artists discuss how their use of AI models has changed their approach to painting, drawing, and photography.

In 2017, Rhea Myers wrote an essay called “Tokenization and its Discontents” about the relatively new use of cryptographic tokens to make digital artworks rare and collectible. To contextualize this phenomenon within art history, she cites McKenzie Wark’s essay “My Collectible Ass,” which discusses how the contemporary art market contrives to sell previously unsellable ephemera. Myers came to the topic through her own art; she made some of the earliest works on the Bitcoin and Ethereum blockchains, having recognized them as new mediums for exploring the ideas of Art + Language, Lawrence Weiner, and other conceptual artists she admired. Wark’s writing on art and property stems from her academic research and theoretical work, in which she extends and builds on Marxist thought to understand the power dynamics of the information age. In a metaphorical sense, Myers and Wark have been engaged in an intellectual conversation for some time. But they recently had their first face-to-face dialogue in a meeting organized by Outland. The two discussed art’s role in inventing new forms of property and ownership, as well as the of experience of making art while transitioning, and the contributions of other trans women to the field of art and technology.

RHEA MYERS At each stage of my life, I’ve made art that has a message for me, and I’ve only realized this in retrospect. I started making crypto art by slamming together ideas from economics and art history. And I got increasingly interested in the idea of encryption.

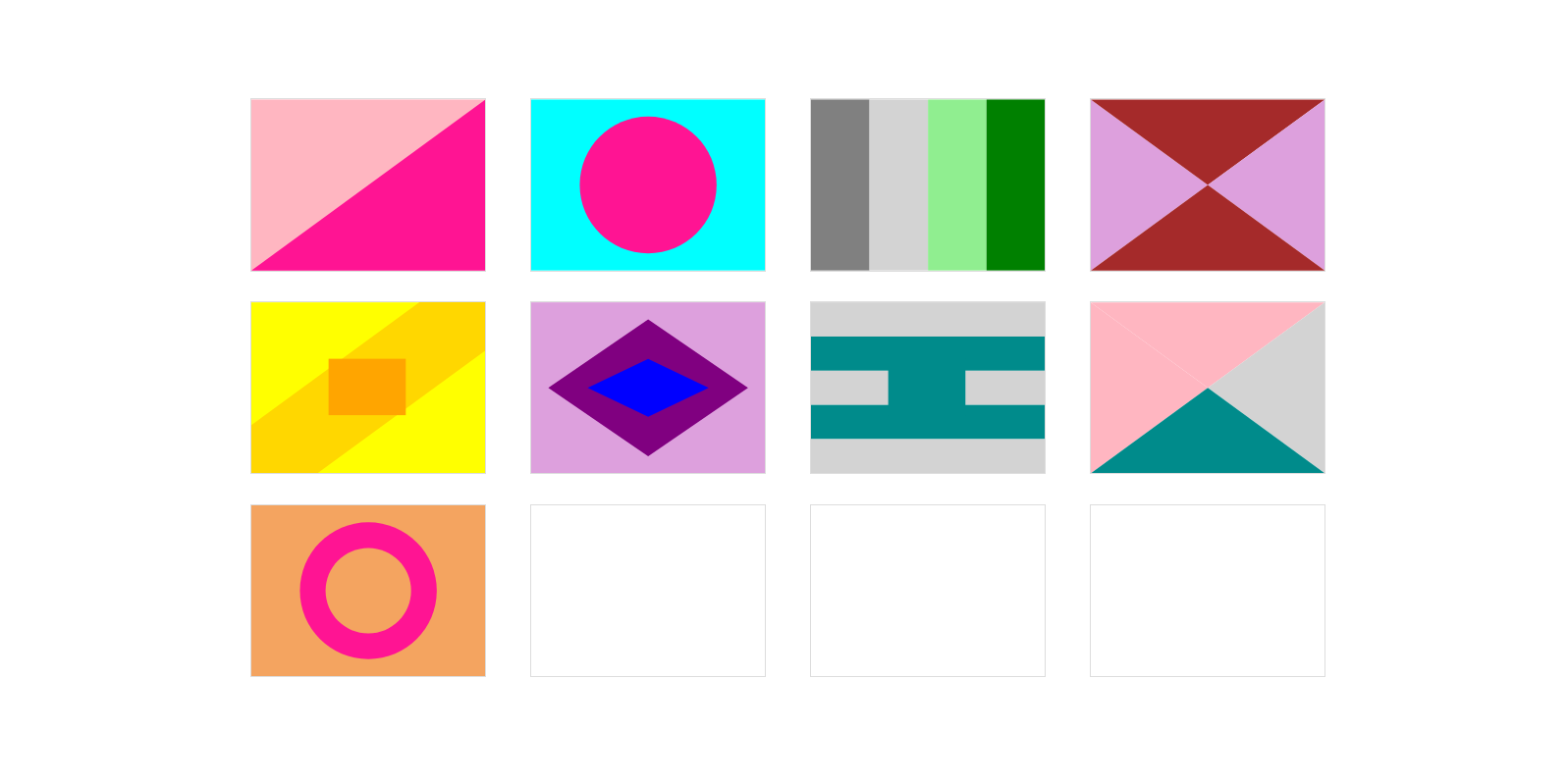

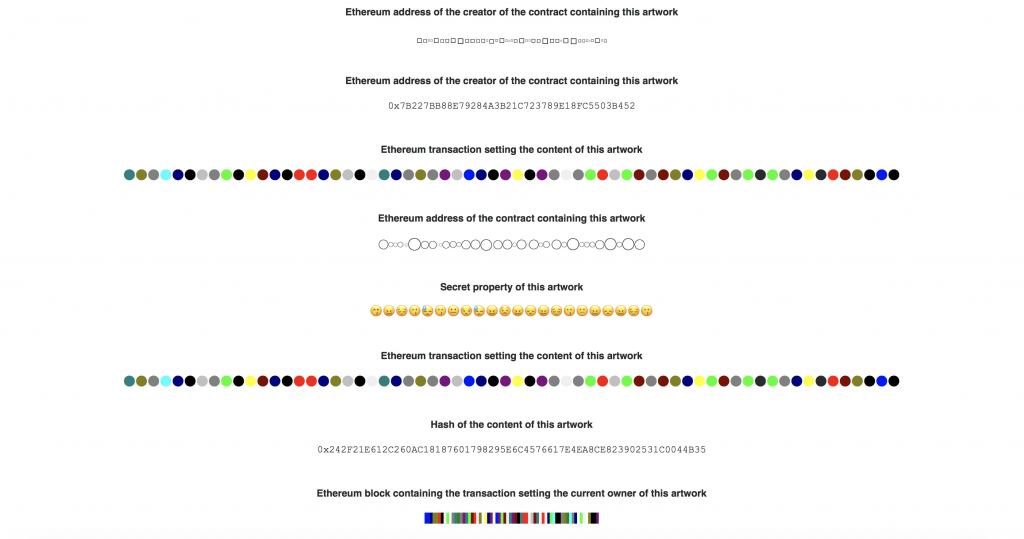

I made a piece that was first exhibited in the old San Francisco Mint, which has these vaults that are lovely big metal tanks underground so that you can’t drill into them and steal the money that isn’t there anymore. That was Secret Artwork. And this is an NFT that has the cryptographic hash of its content on chain with it, but nobody knows what the content is. I used to know, but I’ve forgotten. It’s in a spreadsheet somewhere that I can recover if I’m ever taken to court and I have to prove that there was content. And this comes from conceptual art. It’s based on the old Secret Painting series by Art & Language.

The work has a presentation layer. There’s a nice webpage that goes to the blockchain and gets the information about the token. It tells you absolutely everything about it. It tells you when the contract was made, the address of the contract, when the token was bought and when it was minted, what the hash is, the date it was last transferred, who owns it, who first owned it, the number of the block where all this happened. And it tells you this every way it can: in text or numbers or colored blocks or Wingdings or musical notes. It tells you everything except for the one thing that you want to know, which is what the content actually is. That was 2018. And then in 2021, I suddenly realized that this might be about me, about there being something that was hidden very effectively in my lifetime of experience.

MCKENZIE WARK I think all artists are externalizing things that are opaque to them, and trans people happen to get a lot of that. I don’t think any particular form of expression sums this up, but you can ask: Why did I write that book? Oh, I was trans and didn’t know it.

MYERS With the benefit of hindsight, I feel that SchellingFlags and Certificate of Inauthenticity were just screaming it.

WARK Certificate of inauthenticity is my birth certificate, it turns out.

MYERS Yes. And then to my absolute wonder and delight I discovered that there is a community of young transgender and nonbinary and queer artists who are making art on the blockchain, many of them making glitch art, which has a strong association with trans culture.

WARK We’re all glitches, as Legacy Russell might say.

MYERS Yes. But also the creation of the first glitch art was by a trans woman, Jamie Faye Fenton.

WARK We started a lot of things. Like vaporwave.

MYERS Oh, I listened to Floral Shoppe on repeat for about two years. The very literal sound of masculinity running down and its persuasiveness running out. I had no idea why I liked that.

WARK It’s literally the fumes of that.

MYERS In the introduction to the book collecting the tweets of her @everyword bot, Allison Parrish talks about the experience of having to manage information when you’re trans, in particular when you’re coming out. And that experience of information management was one that I became very familiar with.

WARK It’s not uncommon for trans artists to make work that’s not about the body or identity because those are points of vulnerability. Some trans artists specialize in those things, but there are others who do the exact opposite and avoid anything personal. Emily Zhou makes this point in her essay on Parrish.

MYERS Parrish talks about operating in a culture that simply does not represent you, that does not even regard you as possible, and having to find the resources to express your subjectivity. That’s not exclusively a trans experience, but Parrish describes her experience of it. This information management, the secrecy that encryption and cryptocurrency always appeal to… People think that when you are trans, you are hiding something. But no. Being trans is revealing the commitment. You’ve cracked the encryption and can now reveal what was previously steganographically encoded in your life’s experiences.

WARK Oh, that’s a nice image, I like that. The steganography of the self.

MYERS It’s like coming out to yourself. Extremely online trans culture calls it your egg cracking. That’s a very one-way function. It’s something that you can try to ignore, but it is a revelation of a secret to you. It interested me that my mind fixated on encryption as it was starting to fail to protect me from the realization of my transness.

WARK There’s the Morgan M Page rule, which is don’t make art about being trans until five years into it. But the corollary of that is, if it’s not about transness, the work you make while transitioning is going to be super interesting.

MYERS I made the NFT version of Certificate of Inauthenticity in 2020 after realizing, but before publicly coming out. Certificate of Inauthenticity was about licenses and permissions. I thought, “I can write my old name on here and it will be hilarious ‘cause I’m not that person anymore.’ And then six months later I wanted to exhibit the work and it was physically painful to look at. Fortunately the immutability of the blockchain didn’t screw me that time because the contract let me change the image. But I do have one piece that hashed my old name into the Bitcoin blockchain. I think the obsession with immutability and stable identity, which is being imposed on commercial blockchain projects, is very un-cyberfeminist and it’s very un-Satoshi Nakamoto. So that’s definitely a site of a struggle.

WARK Your early work in the net art domain was outside of art as a form of property. Can you tell me about that work, and how you segued out of that into an R&D in new forms of property?

MYERS I went to art school in the early to mid-’90s, so it was very easy to pick up books on appropriation art: Sherrie Levine, Jeff Koons, Andy Warhol, Barbara Kruger, and anyone who was “stealing” other people’s imagery, doing something interesting with it, and getting into legal trouble for doing so. Art law was fascinating to me, because it’s a structure of knowing and understanding and perceiving. I encountered this supposedly free space of artistic commentary on the spectacle, and then watched it be whittled away by legal decisions that said if you’d like sample one note from a song you have to get a license, or if you copy a tiny bit of a picture you have to give some of your rights away. It’s easy to be on the side of edgy, radical artists when they are taking from the mass media and doing stuff with it. When it’s multimillionaire artists taking from Instagram, the equation changes.

WARK Richard Prince would be an example of that—borrowing from unknown Instagram artists.

MYERS Absolutely. I first got some art on the internet in 1994 at the typography conference Fuse ‘94, where I very quickly made some images in Photoshop and then FTP’d them up into webspace. That is further than archive.org’s memory goes back, so it’s lost to time. But I didn’t get net art. As far as I was concerned, PDF was much better than HTML. I thought interactive multimedia gave you a much richer experience than texts on a mailing list. So I was looking in the wrong direction and it took me a while to catch up.

When I did catch up, this question of property, power, and control was central. Work, entertainment, leisure and shopping or consumption all very quickly fell into the web. That really interested me as a new context that had not yet been entirely closed down as the space of appropriation art had been. The earliest things I did were little Java applets that generated Damien Hirst spot compositions. Due to technical difficulty, they were exhibited as a URL in the gallery. So I have an early entry in that genre, not due to artistic brilliance, but due to technical limitations.

WARK Isn’t that how a lot of things happen?

MYERS I do find that, yes. I’m worried about more powerful programming languages arriving on the blockchain, because it means I won’t have limitations to kick against productively anymore. Anyway, that spirit of sharing, that very European reaction to the Californian ideology led me to Free Software, which again, I was very late to. Free Culture and Creative Commons just clicked as a way of recovering the playground of remixing, of sampling, of appropriation art. This is a common narrative in politics: we must retake the thing that has been taken from us.

WARK I know the idea of Californian Ideology from participating in the nettime.org listserv, which was my home for the avant-garde practices around this. And just to fill in the blanks, the Californian ideology is a term coined by Richard Barbrook and the late Andy Cameron to come up with that utopian, manic language of market technology as the future. There is so much of that around blockchain now, isn’t there?

MYERS There really is. I would shorthand the Californian ideology as an ethic of extraction with an aesthetic of sharing. Early ’90s internet utopianism appears more utopian in retrospect.

WARK There were two different utopias. Ours was the commons. Information wants to be free, but it was in chains. The other one was: information wants to be free, how do we put it in chains so that we can extract value out of it that no one knows how to extract yet?

MYERS Cory Doctorow had a lovely quote about how making information harder to copy is like trying to make water less wet. Net art hit on the critical possibility of propagating information through networks. If we go further back to the conceptual art era, information is not just zeroes and ones. Information is knowledge of the world, it’s political ideas. The idea of information as something neutral has never been the case in the art world, by my understanding.

WARK Yes. People keep reiterating that information is not neutral, but who thinks that anyway?

MYERS There’s no techno-determinist like a critic of techno-determinism. I’m very much a poacher turned gamekeeper. Those of us who work in the crypto space are acutely aware of the limitations and risks, as well as the opportunities and potentials. And this is true of each successive technology. People who look at any new technology and go, “This is going to be used to oppress us, isn’t it?”—my heart goes out to them.

WARK Well, there’s a tendency to treat technology as an agency that has some essential property, rather than a site of struggle, where people are fighting both internally and externally to it. What do you mean when you say you’re a poacher turned gamekeeper?

MYERS In 2014 I started making art using the pre-release Ethereum blockchain. It was purely for play, it was purely for art, it was purely critical. I accidentally learned as much as it was possible to know at that time about the technology. Now I’ve just finished working for Dapper Labs, an awesome company that makes its own blockchain. It’s a very different experience writing a bit of code that’s going to handle tens of thousands of dollars of real world value, compared to something you’ve carefully structured so that it can’t handle any real world value at all, and you can hide behind the concept of art if anything goes wrong with it. So that’s what I mean by “poacher turned gamekeeper”—going from this very freewheeling critical view to a no less critical, but embedded position.

WARK The problem I have with most of the critical views about blockchain is that they come from people who don’t know anything about it, because they’re looking at it from outside. I don’t claim any knowledge of this area because I don’t do it, but I’m interested in people who do know things about it. That’s a starting point for an art practice, right? You start with an indifference to materials. That’s Duchamp’s principle of the readymade. They were selected on the basis of “visual indifference.” You could also start with any kind of code on the basis of “computational indifference.” Then you figure out how it works.

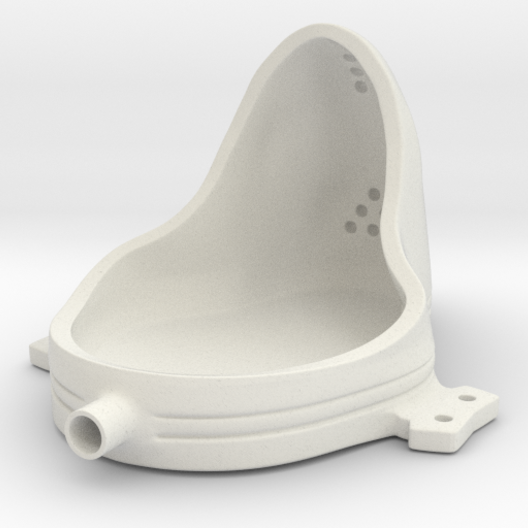

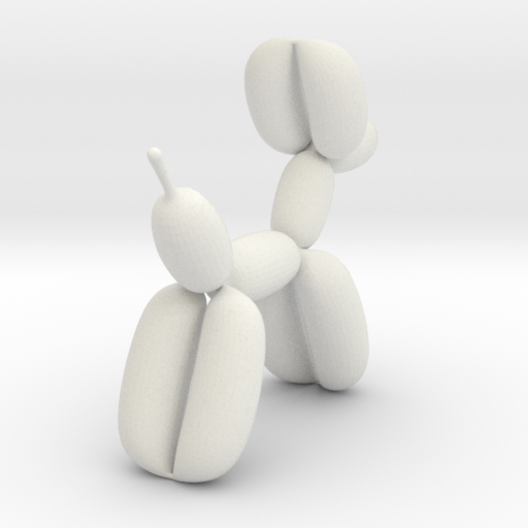

MYERS I sadly and unironically love Duchamp. I did a project about a decade ago where I commissioned some talented 3D modeling artists to make 3D models of iconic objects from modernist and postmodernist art, objects that had been sort of removed from our shared cultural commons and attributed to Duchamp or Koons. We produced the urinal, the balloon dog, and a couple other things. We licensed them under Creative Commons, so anyone could get them from one of the 3D model sharing sites and print them out. And any attribution goes to me as the evil artist running the studio and the copyright remains with the actual artisan because it’s their creative labor.

WARK I’ve done that too. My #3Debord figurines were made by a very talented toy designer whose business had been through a phase shift. It all used to be based on carving in wood and working with artisans. Then it all went digital. I asked him to design a toy that was Creative Commons licensed. All hell broke loose because you’re not supposed to make a toy out of Guy Debord, even though people copy and paste his picture everywhere. It’s ironic that people think that Guy Debord is their personal property.

MYERS I know. It’s bizarre that someone can own the idea of a urinal or a balloon dog or whatever else to the point where they will sue museums or galleries that sell merchandise that looks similar.

WARK The paradox is that the value of the unique object is only multiplied by its copies, as I argued in “My Collectible Ass.” There’s a way in which this obsession with shutting down copies probably decreases the value.

MYERS In many cases art is a tool for ideological closure, or resolution of contradictions, or presentation of the absent. Art shows what we know to be true about the world and how its systems work, yet is presently absent or cannot be seen. In the contemporary art era, the artist is a manager in an era of managerial culture.

WARK But the Dutch old masters were managers of their studios. So modernism is the exception. The work of the artist is running a studio. Other people do most of the work on the actual art. There are people grinding pigments and bartering in the market for what each pigment would be worth. Art evolves with different eras of commodification. It sometimes anticipates them. Ironically, a lot of modern art now looks sort of anachronistic and old-timey. It valued craft at a time of mass production, or pretended to be mass production when really it came from an atelier with three people. What does the era of the NFT artwork tell us about what commodification is now, or what a financial instrument is now?

MYERS I’m going to sound horrifically naive. I think that the kind of dynamic that I was playing with in the 3D models and their Creative Commons license indicates a separation of ownership from social prestige or a position in a chain of possession. With an NFT, people who point out that you can right click and save the associated image—yep. Well done. That’s absolutely correct, and that’s a good thing. The separation of the reputational and financial category of ownership from the category of possession has been happening for a long time, with certificates of authenticity and authentication committees for fine arts. And you can absolutely try to deploy the violence of the state to glue them back together. So it will eventually be a crime to right click and save. SWAT teams will crash in through the doors and tell you that you’re taking money from the mouths of starving executives at illustration companies.

But instead of fixating on that, we can delaminate possession and ownership. We can make the NFT the number in the ledger that is the focus of ownership and transfer and value and possession. Then people off-chain, in meatspace or in cyberspace, can do whatever they want to with the resource of the NFT it is still infinitely reproducible. And we see people doing this with CC0-licensed NFTs.

WARK If you deal with any big media company, you quickly learn that they have a legal department trying to turn every instance of the use of that property into value. But they also have a marketing department that is giving that stuff away free to anybody who will talk about it. So there’s a contradiction in how that model works. There’s kind of tension around how information becomes a commodity. Information is just inherently, constitutionally, not self-identical in the way a piece of property is supposed to be.

MYERS You’re absolutely right. Disney has been screwing up American copyright law for the last fifty years because of how much people love these properties, this IP, to use that horrible term. Meanwhile, the vectorial class introduced the idea that you can make products of creative labor free and then exploit that to make yourself fantastically rich by charging for the network connection.

WARK That was what happened. We won the battle. We established this little area where stuff can be free, and then it was commodified at a more abstract level. They commodified the extraction of the sum total of that value, and we can move these little bits around as much as we want. News corporation and Disney will persist with these ridiculous models of digital rights management and demand more power than the North Korean state to spy on your computer lest you break their sacred right to keep collecting the rent off the carcass of Mickey Mouse or whatever. But that ownership of stocks of information got outflanked by the owners of the vector over which it flows. Or the system of its addressability. Google, for example.

But the other interesting thing about the NFT space is how it perfects the bit of the art world that was provenance, and treats it as separate. You’re freed from having to handle these expensive, rare objects. It’s about ownership in its pure form. Were you smart enough to figure out that NFT was the one to own at that moment? Is that recognizable as a qualitative moment in possession?

So it’s the pure art of ownership, but sometimes there are little illustrations to go with it. But in a sense the art is somewhat arbitrary. It just has to be qualitatively different from everything else. Everyone knows that’s how the art world already works, but it comes with cumbersome objects that require special handling. NFTs do away with that and just leave a pure system of provenance.

MYERS I got shouted at for saying this on a panel the other day, but there’s a strong anti-aesthetic to the most popular and successful PFP NFT projects—the Apes and Punks and whatnot—and that interests me. I suspect that the nonfungible token is in fact fungible as part of this allover artwork of purely ownable things, which just have to look different enough from other purely ownable things to be identifiable.

WARK It’s a beautiful deskilling of the aesthetic side of it. Just like all other forms of creation get deskilled. The role of the artist is to produce minimal tradeable difference, but ownership is really the key.

MYERS Yes, it’s a commodification of it in the sense that it doesn’t matter to who produces it.

WARK It does seem of a piece with this tendency in financial markets in general for the derivative to be more interesting than what it’s derivative of. Most so-called capital is just information about other information at this point. There’s some real economy under there somewhere, but that’s just one of the metrics being measured.

MYERS I wrote an essay ages ago called “Vampire Digital Art,” which suggested that these derivatives could be used as the form from which you make art. This is the thing that reflects the ego of the paradigmatic viewer, who is the competent investor, the master of the universe on Wall Street. It is a representation, as you point out, that is crafted to relate somehow to the materials of the real world, but to represent them in a way that flatters this viewer.

I couldn’t afford the insurance to do something like that, but art financial instruments are in many ways the perfect medium for making art, both in terms of being the most beautiful thing that a hedge fund manager could possibly imagine and as an opportunity for disobedience in obedience.

WARK There’s a history to that, like eToy selling shares in themselves. Goldin+Senneby had a lovely project based on short selling that actually made me money. They got asked to do a Christmas card for this very obscure little financial firm that was in short-selling. They take out a contract to sell a stock for price X on date A, then the price drops to less than X. Buy at that price, fulfill the sell contract, pocket the difference. There’s something curious and murky in-between where certain finance journalists badmouth the stock in question. I put in 200 EUR and it made me 400 EUR back or something. It’s my best art investment ever and it’s just a little piece of paper representing something that never happened. I had fun explaining that one to my accountant at tax time.

MYERS Capitalism enjoys it when you resist, because that’s how it finds new things to enclose. Capital grows by absorbing critique, by recuperating alterity. And art is part of that. There was an early version of NFTs called Rare Pepes, based on the frog character, who has been reappropriated from the alt-right, I must point out. A group of people were joking around and talking about finding the rarest images of Pepe the Frog and someone tried selling them on eBay. Then someone found an early token system based on Bitcoin called Counterparty XCP and they started making Rare Pepe trading cards on the blockchain using this token technology. This wasn’t something that came from a large media company’s R&D lab. It came from the kind of internet sociality that has been the norm for many different groups of people for a couple of decades now. And this particular group came up with an idea that they migrated into an early blockchain system.

There’s a section of blockchain art history that looks kind of strange, because everyone is talking about “rare” digital art. There are platforms or companies with “rare” in their name. Why say it’s rare? Anyone can copy these things. But it comes from an innovation that parodied of ownership: “Haha, imagine if you could actually sell this infinitely copyable digital image.” Then people with access to VC capital said, “Imagine if you could!”

WARK The whole history of commodification meets aesthetics is people asking: how do you extract value out of something which is not yet property? You make it a thing so you can extract value from it. I think there are lessons to learn in this history from Black artists in the United States who often wanted to own and make money from what they produce. And one has to expect that because they were formerly owned. But that cultural work got appropriated, and they had to go look for something else. When the thing that you made got stolen from you, you go look for something else. White people need to learn from that because we have assumptions about being property owners rather than being property, or indebted to property, that haven’t been beaten out of us yet.

MYERS You’re absolutely right. The history of copyright for music in particular is very much about music that has a “fixed form,” like sheet music and then mechanical recordings. If you’re in a shared social space making music, then it’s not in a fixed form, you’re improvising it or it’s an oral tradition. But if someone comes along, and writes it down or records it, they have it in a fixed form. And this is, as you point out, how blues did not financially benefit the people who lived it for years and gave everything to it. And yet if a rap musician wanted to sample a mechanical recording of the same track, they would get sued into oblivion by the mid-’90s, because that was a fixed representation. Which property owners benefited from copyright as it evolved? At each point it does look suspiciously racialized, to put it mildly.

Someone on Twitter was talking about these PFP projects of ten thousand images on the blockchain being the gentrification of a form used by young women, racialized minorities, queers. Doing your reversed gender PFP is a transgender rite of passage for many young people. The cartoon image as PFP is a form whose value was built by people who are underrepresented and exploited. And it’s being enclosed away from them once again.

WARK Once upon a time, the only property that mattered was land. Along comes capitalism, and what really matters is owning the means of production. Then information became something you could then outflank that with. You don’t have to own either the land or the means of production. And you get some whole other economy, and we’re still exploring the possibility of it. That’s how today’s ruling class operates.

MYERS Absolutely. At each stage, you’ve got this Lockean idea of unclaimed raw materials that just so happen to be lying around, whether it’s mysteriously depopulated territory in North America or songs that you hear when you go to a particular club. at the edge of town. And you’re absolutely right about abstraction. To a degree, NFTs are a sort of a fairly pure abstraction of ownership. Because what do you own? You own the ownership.

WARK It’s conceptual art perfected in a way.

MYERS Conceptual art’s use of information technology, its challenge to existing systems of ownership, exhibition, and exchange, are recuperated through certificates of ownership. I recognized this as a template for crypto art—conceptual art as million-dollar goods.

—Moderated by Brian Droitcour