Rhea Myers

Rhea Myers, who has been making art using blockchain technologies since 2011, discusses her pioneering work.

Ryan Kuo and Zach Gage are artists that use digital means to design evocative interactions, but towards different ends. Kuo makes process-based work employing video game engines, chatbots, and other tools to evoke moments of unresolved tension. His work Hateful Little Thing (2021), recently exhibited as part of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s “Sunrise/Sunset” series of web commissions, hijacked the museum’s curatorial branding to inundate users with frustration-laden messages that argue against its support. Gage, a game designer and conceptual artist, creates inventive and intuitive app-based logic puzzles, including SpellTower (2011) and the recently released Knotwords (2022). While artists working digitally celebrated new avenues for success during the NFT boom of 2021, Kuo and Gage were among those who grappled with the implications of tokenizing their work. Both Kuo’s illustrated essay for Fulcrum Art, Square Hole (2021), on the concept of value in NFTs, as well as Gage’s untokenizable work Scarcity (2021) explored the artists’ complicated relationship to ownership and the blockchain. In the following conversation, the two discussed the impetus for these works, as well as the relationship between metrics and their approaches to artmaking, and the role of history in understanding how artists work with technology.

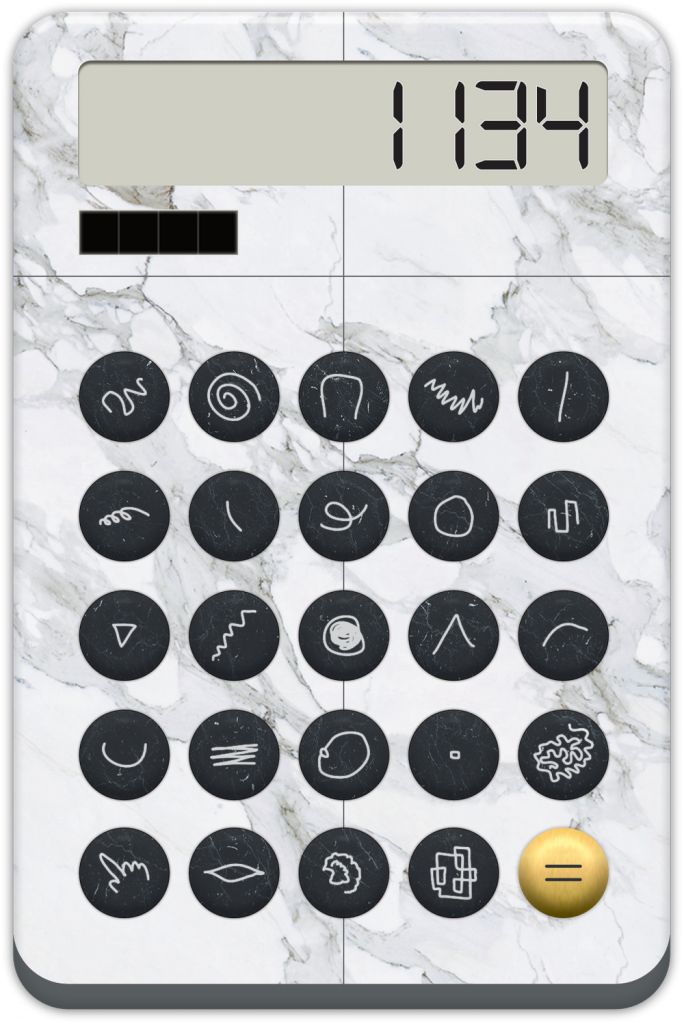

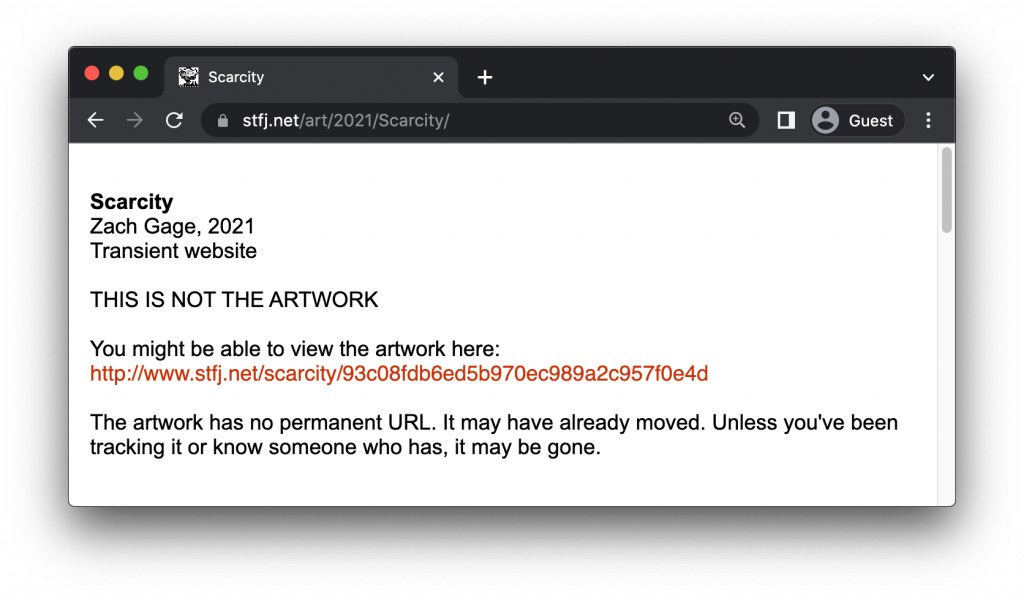

ZACH GAGE The function of Scarcity was to find a way to say something about how conflicted I was feeling about NFTs at the time. A main element of the work was the inability to connect it to an NFT because at the time everything was getting tokenized, sometimes without permission. The way Scarcity works is that it hashes the starting date it was created, and then roughly every one hundred days or so it will randomly move to another URL based on that hash. It hashes together the date information of all of the times that it’s moved, and then creates a new host link that incorporates the ledger of all of those previous dates.

I didn’t want it to move more frequently, because I didn’t want the tracking of the work to become some sort of fun game—a hundred days felt like enough time that you could grow bored of it before it decides to move, and then it would move and you’d miss it. So, the only way to keep track of the piece is if you yourself have kept track of every time it’s moved, and then use that to track it on the moment it moves again. The more the work moves, the more it becomes irrecoverable, so it was meant to be a work in which the method of ownership was more of a process of owning, rather than a concept of owning. That “process” is closer to how I feel art ownership should operate: when you have a work of art in your living space, you undergo a process with it because you’re growing and changing over time and you can reflect on it in different ways. It’s not a binary status that can be encoded. Instead it’s a process of building a relationship with the work.

RYAN KUO This idea of ownership as a binary state is exactly where I get hung up with regard to the idea of collectors owning my work. With the essay and illustrations for Square Hole, I was responding to what I feel have been false equivalences around the word “value,” and this assumption that we all need to believe we’re worth something.

Once you apply a structure like an ERC-721 specification onto the notion of being worth something—and not being worth less—questions like “how much exactly am I worth?”, or “how much is my work worth?” follow. Then it becomes a game for you of trying to anticipate and price your work correctly, and a game for collectors of knowing when to invest. For me, the idea of someone owning my work is still an open question. How does someone arrive at not just wanting to engage with my work, but wanting to actually possess it? That’s an act of going from zero to one that I haven’t solved for myself. It’s not intuitive for me.

What you’re saying about ownership as a process is helpful because that’s how I think about the things I own and the works I relate to. I think that it does often seem like a binary relation when people discuss owning NFTs because people want to know how long to hold onto them before they sell. It feels like it’s two points on a key-framed timeline—when it comes into my hands, and when it’s leaving my hands—like a simulation of a continuous relation.

GAGE This reminds me of a period in 2016, when I had a show at Postmasters Gallery for a project called “Glaciers.” It was a time when I felt very frustrated with the internet, and it was interesting for me to do a show in a traditional gallery space after years of releasing work and games online. After the opening, I had no idea how it had gone because real life doesn’t have any metrics to it. I couldn’t say how many people were there. I didn’t know how long people were looking at the work. When I release a game, I know how many people have downloaded it, how many people have bought it, and how often they’re playing. I try to avoid those metrics because they tend to stress me out, and yet, after the real-world opening of my show I felt lost without them

There’s a tyranny of numbers. People are desperate now to apply numbers to anything because it reduces the complexity of things we’re interacting with to try to make them understandable when often they fundamentally can’t be. You could imagine a version of life in which somehow I had metrics from that opening, but they wouldn’t be useful for anything. There’s nothing that would come out of that that would be more meaningful than my experience of being in the place and feeling what it was like at the time. Numbers are desperate to convince us that the things they represent are meaningful, and are helpful. That’s why speculation is the part of art that I care the least for and find the least interesting. A lot of the culture of what exists in museums, and what artists are popular, is a product of speculation to some degree, but the actual act of speculating isn’t something that we’re often directly engaged with.

KUO I’m not quite aligned with those of my peers who think the entire structure of the NFT market should be dismantled, because I feel it can be useful in understanding our relationships to ownership and engagement. Observing how different user interfaces, and metaphors of understanding, pop up around the barebones structure that administers updates to a database ledger is a concise summation of the fact that people need to feel like they have gone somewhere and taken an experience in, or that they are engaged with some form of reality. Through a certain window, you can see the new audience of art collectors chasing NFTs almost as a simulation of what it means to appreciate art and appreciate artists.

From what I’ve encountered personally with NFTs, it feels like there’s a lot of looking past what’s actually in the file in favor of trying to access the market logic beyond it. It’s similar to when people talk about an opening going well; maybe they’re trying to access a vibe about what the health and state of the art world is currently. Neither of those things is about an actual kind of engagement or confrontation with a piece of art, in the end. The more disturbing encounters I’ve had are those in which I’ve felt people are claiming to see me and appreciate me as an artist when it’s very clear they’re looking straight through me into a realm where I’m not trying to go.

GAGE For me, one of the major purposes of art is that it provides an alternative history that you can look at and use to understand the time. That’s the way I prefer to think about NFTs, and what’s happening now. You can see glimpses of that when you look at something like modern art as a lens to view how culture shifted after World War II. This idea of art as history didn’t really hit home for me until I was in graduate school studying the history of net art, and wondering why the vibrant scene had seemed to disappear around 2003. I ended up discovering that I shouldn’t be asking why it disappeared; really I should be asking: why it was there in the first place? I didn’t understand the broader cultural structures that led to how artists were operating at that time. It made me realize that art is a version of history that isn’t written by the winners or losers—it’s written by people who are taking the emotions and experiences of the time and trying to crystalize them. There shouldn’t be things that are off limits to artists, because you don’t know what things will be like in twenty or fifty years.

KUO I recently read a catalog about the Godzilla Asian American Arts Network, which was founded in New York in the nineties. It was my first experience of being able to connect certain encounters that I’ve had in the New York art world with a broader historical arc of relationships that were formed and that evolved over time. Briefly, there was first a move for inclusion in institutional spaces for Asian artists, which then became transmuted into diversity and inclusion initiatives, which then ended up structurally tokenizing them.

As artists, we’re all thrashing around, trying to come out with semblances of understanding, or artworks, that can help channel deeper understandings of things. What continues—with the nowness of this discourse, and new technology—is not just that there are periods of time in which things are unclear or poorly understood, but there are times when people are being violently misunderstood. I frequently have to counteract assumptions about what my intentions, or what our shared values, might be. In my work, I’m often trying to take the images and words that stick with me from those experiences, and use them as ways to break apart some of those misunderstandings. I see it as less exploratory and more as an ongoing kind of argument, but it’s hard for me not to feel defensive at the same time.

GAGE It’s admirable that what you’re doing with that defensiveness is trying to conceptualize artworks based around the experience. That’s an elegant and important thing. I think it’s always better to attempt to translate your experience than it is to attempt to translate only your reaction. That’s a really important aspect of art. What I found so fascinating about your Square Hole essay is that you were able to translate what you found difficult about the NFT space, but also how the complications of understanding it are current and compelling, and unique to this moment.

KUO There are two aspects of my work that deal with these experiences and my response to them. First, I often make work that is autonomous, self-playing, or self-generating. I’ve been working in Unity for the past few years to set up situations that don’t accept player input, and instead use a stochastic network of cameras that jump between different views, scenes, and actors. In a work like Nouns (2016), it’s as though the computer is directing a never-ending sequence—works like Hateful Little Thing do this with language as well. The way I would read it in the context of this conversation is that I’m trying to take up a lot of space, and I’m using the machine to edge out other forms of interruption, which might include a certain type of player who has certain expectations. That’s become more and more literal as the processes within the works have started to embody my sensibilities, or function as stand-ins for my personality. That’s why I’ve always found it hard to think about someone owning my work, because it already feels like a piece of me. It’s a proxy for me.

Second, I think it’s interesting because we’re both working in a neutralizing sphere of affect, but we’re coming in from very different angles. I work with innocuous, extremely dry, or bureaucratic-seeming platforms like web UIs or marketing chatbots. I’m drawn to them because it’s always very clear that these softwares are not meant to be used for creating art, and what I find energizing and meaningful is when I can tell exactly what a certain tool expects me to think of it while also anticipating what I might end up making of it. What I’m drawn to in your game works, like Knotwords and SpellTower, is that it seems you’re going for a very specific kind of atmosphere, too. These games, and their UI blips and music, bring me back to Windows 95. They’re good examples of the sort of games that will slide into people’s dead time, or people’s attention span.

GAGE The context of how you describe your work is helping me understand something that has never really occurred to me about my work. I think it would be fair to describe my art practice as provocative, but not in the way that most people use that word. Provocative things are usually bombastic; my work is provocative in the sense it forces you into having an experience that is very specific. Once you’ve had that experience, then you’re left to grapple with what it means to have had that experience.

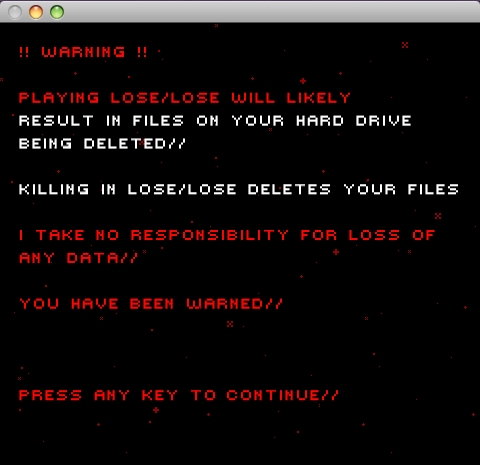

This goes all the way back to a game I made in 2009, lose/lose. It was a Space Invaders style game where if you shot the invaders, they would delete random files on your computer. The entire concept of that work was to force people into admitting that the things they had on their computer were valuable to them in the same way that things in real life are valuable to them. With Scarcity, I thought if I could build something that can be lost, the anxiety of losing it is what you are forced into through the structure of the work.

There’s a big educational component to my games, too—I’m trying to get people to think critically and understand that interaction is design that surrounds us and is worth interrogating. That’s what led me to working with tools that most people understand, like card games or word games, because those are easy ways to reach a lot of people. From there, I need to find an experience that requires critical thought and engenders interaction literacy, while being interesting and compelling. Then it’s a matter of accommodating and guiding the user towards that game experience, even before they download the app.

KUO I’ve played many kinds of games that are trying to guide me as a user, but I often feel that someone is attempting to pander to me. What I appreciate about your work is that I can sense you’re very aware of what you’re constructing, and why. The pleasure I get is through the vicarious experience of all the acts of accommodation and politeness that I’m trying to get away from, and not fall victim to in my day to day encounters, which are expressed in the design of one of your apps.

I grew up learning that I should be accommodating as a non-white person in America. I have a very instinctual drive to leave room for voices that have more power than I do. That’s maybe why I’m often told I’m a good listener, because I’m trained to validate what a person is saying to me, reflected back in the tone they’re expecting. Sometimes I’m specifically trying not to do that with my work, but more often I’m trying to toe the line where I’m demonstratively playing those encounters out for the viewer. I work with systems that enforce a kind of boredom and bureaucracy because those are the structures that are often enabling and prolonging the misunderstandings, and the rush to procure a certain something from someone else that they might not be willing to give.

GAGE I think my work is using the language associated with being accommodating to operate and trick users—not in an evil way, but in a sense that I’m trying to understand patterns of behavior and work with them to reach a goal. It seems you’re trying to work outside that structure by using more bureaucratic tools to undermine those systems. Your work is intentionally trying to get away from that. You’re not trying to entice people with anything less than the totality of what you’re talking about.

KUO I think there’s a performative aspect where I feel I have to shoulder the burden of these good design principles or good UX that are being used to hook us on certain kinds of behaviors and metaphors of relation. I’m very painstakingly taking those in and trying to bend them one by one into a new shape in the end. In and of itself, that process has come out of this acculturated habit of overaccommodation. I’m taking what I do at my day job at a tech company and applying it to an art practice. You described what you’re doing with certain tools and wanting to do everything you can to direct users to a specific experience. My experiences growing up and as a body make me feel that I’m constitutionally unable to do that.

GAGE That’s another way in which your work is embodying the moment that is not fully surfaced. There’s an interplay in what you’re doing where it feels to me that you’ve found a place where you can be a radical while still succeeding at feeling like you’re being accommodating. You’ve managed to do it in a way where you feel comfortable because you locate these bureaucratic zones that are ready to be occupied. I wonder how that factors into the experiences and observations about the NFT space, and your work there?

KUO None of that is by design, but it came out of a certain kind of relation to a dominant culture. The interactions with collectors and NFT prospectors that have been disturbing to me are those in which I’m feeling the depth of their expectation and their own sense of the power that they think they have, or maybe do have, due to the amount of capital they’re sitting on. In the same way that this one-click collecting framework is being built around me, I feel a real threat in being expected to help engineer one-click relationships to myself and to my work.

GAGE I think that’s an important contextual component of what crypto fundamentally does. It’s a way to bring a free market to any space, which is a substantial, powerful thing to be able to do. When it’s done, everyone in the space becomes either a vendor or a customer, which comes with a whole host of expectations that are totally different from being an artist.

—Moderated by Lauren Studebaker