Harm Reduction

Kyle McDonald calculated Ethereum’s carbon footprint. Now he’s asking NFT collectors to pay reparations.

On a Sunday morning in 2002, Sara Ludy found herself in an unfamiliar room in a house she didn’t recognize. It was only after attempting to look into a mirror that she realized it was a dream and awoke, shaken by her experience of a different reality. Another vivid dream involved a midnight meeting in the kitchen with the spirit of a recently passed friend. The American artist has shared these stories of her nocturnal adventures in interviews; they inspired her Dream House project (2014–), a sequence of videos that move through sleek, refined, and minimal rooms, washed in a muted palette of purples, blues, and grays. An audio track provides white noise, giving these interiors a clinical atmosphere. Ludy makes these videos by projecting her rooms drawn with digital tools onto real walls and shooting them with a camera. The supernatural content of Dream House is centered through a process of intuitive making that translates Ludy’s dream experiences into virtual reality, in dialogue with physical space.

Ludy’s varied output includes live musical performances, environmental art, and traditional and digital painting. Her techniques and tools vary widely, but the theme of space, both virtual and natural, unites her work. Ludy takes her audience on a voyage beyond the screen, where the boundaries between organic, digital, and subliminal bend and blur. These hybrid explorations make viewers more aware of the spaces through which they move by spotlighting the often unnoticed overlaps of real and digital worlds. For Ludy, the two have always been interwoven. She grew up watching Bob Ross’s “The Joy of Painting“ on Saturday mornings in a small town in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. She began to experiment with audio collage as a teenager using a Tascom Porta 07 four-track cassette tape recorder, and made videos using closed-circuit security cameras she commandeered from her mother’s business. She scrawled sci-fi-inspired drawings using MacPaint and learned Photoshop in high school before attending the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she enrolled as a painter—but an interdisciplinary new media course eventually inspired Ludy to turn in her brushes and oils for software. She was drawn back to her early explorations in digital painting, growing that practice into spatial explorations of digital immateriality.

Dream House is one of many works by the artist that explore space and architecture—an interest that she has also cultivated through her work as an interior designer. Sets (2012–14) is a collection of drawings that conjure rooms, lobbies, and hallways in a warm and nostalgic palette of black and purple alongside abstract images inhabiting fathoms-deep digital picture planes. Low Prim (2012–) consists of a massive archive of digital images Ludy has collected for two decades and counting. Prims, short for “primitives,” are the building blocks used to make everything in Second Life, and the images in Ludy’s archive serve the same purpose in her creative practice. Low Prim Room includes grids of projected images of waterfalls, urban architecture, a businessman in a suit, and a pair of women aquacising in an azure swimming pool. When exhibited at Bitforms in New York in 2016, the projection was paired with other physical elements and objects that balanced the space in accordance with the same feng shui design principles that inform Ludy’s Dream House interiors.

These digital landscapes are thoroughly immersive and beautifully eerie.

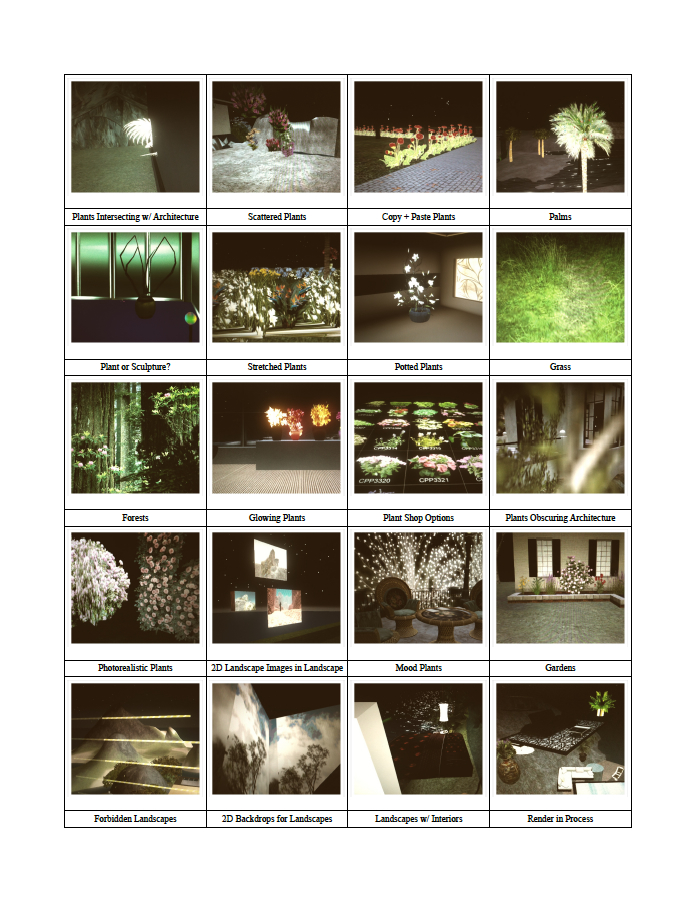

Ludy uses her phone camera to capture both physical and virtual spaces, obscuring differences among forms like plants, bodies of water and clouds as they appear across and between the two. In Projection Monitor (2010–15), she deploys photography and field recordings like a naturalist, but in the virtual spaces in Second Life. This has yielded a number of image collections, like Plant Classification (2011), which features digital plants in virtual environments and real plants in physical ones, as well as photos of plants digitally projected onto real walls or digital images of real plants that Ludy re-photographs on her laptop screen. The taxonomic labels—“Palms,” “Grass,” “Plant or Sculpture?,” “Plants Obscuring Architecture”—make no mention of the images’ natural or virtual origins, leaving viewers to sort the sources and decide whether or not they even matter. Beaches (2014) captures moving images of pixelated peacocks and inflatable swim tubes bobbing on monitor-screen-rippling waves. These digital landscapes are thoroughly immersive and beautifully eerie, and the videos, shot with a handheld camera, cast their viewers as uneasy witnesses in these virtual spaces.

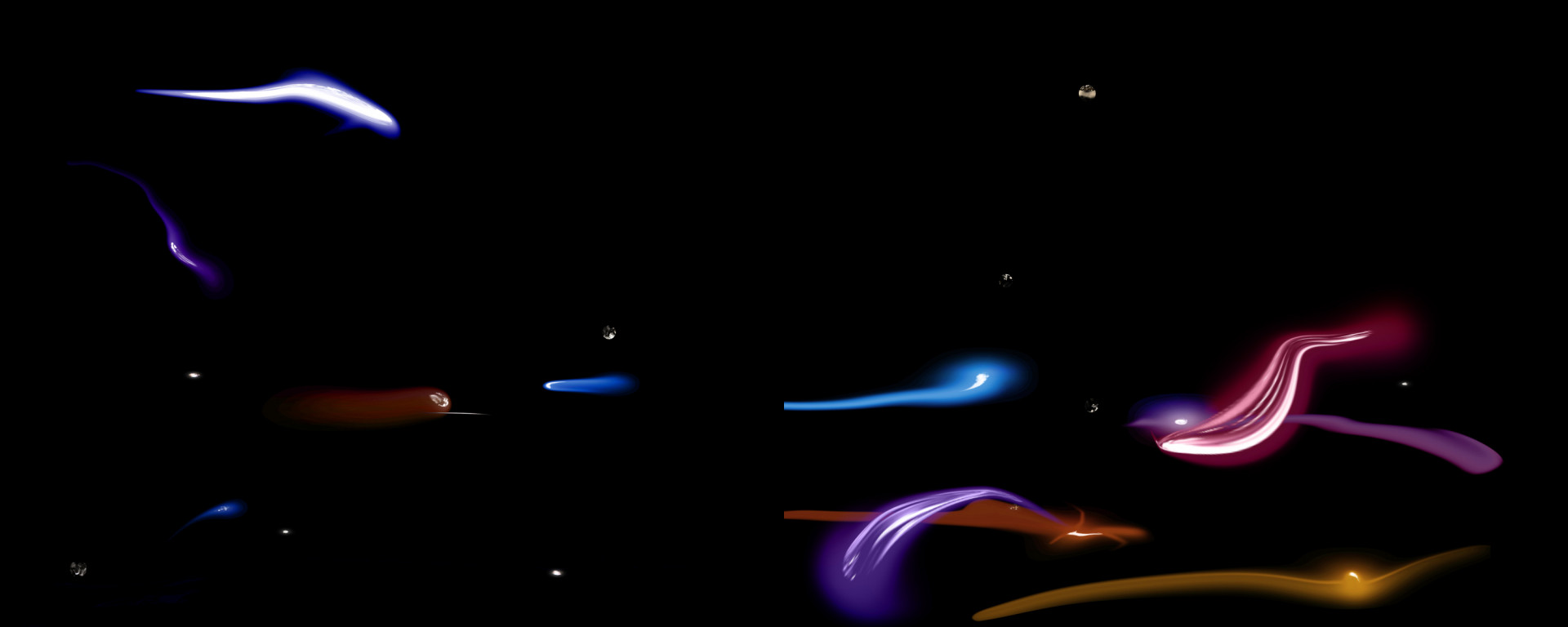

Ludy’s latest project, Tumbleweeds, is a commission for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s “Sunrise/Sunset” series of internet art projects. The artist scoured New Mexico’s desert landscapes for her project just as she scours the obscure corners of the internet for her found images. But instead of finding weird jpgs and broken links, she caught actual tumbleweeds and dug up broken glass, which she tied together with biodegradable twine before releasing the assemblages back to the desert. Short videos capture the flashing shards of glass as they tumble along with the weeds and fall back to the desert floor when the twine wears thin. The flashes on the video clips register as streaks of colored light on an evolving, animated map on the Whitney’s website. Tumbleweeds uses natural materials in a real-world setting to generate a virtual painting in a digital representation of that same desert space. The project encapsulates Ludy’s practice, as it required both hands-on knotcraft as well as a reliable internet connection for updating the online map. Like all of Ludy’s best works, Tumbleweeds is natural and artificial. It’s technological and painterly. It’s wide awake and dreaming.

Joe Nolan is a multimedia artist, writer, and musician based in Nashville.